It was by instinct that I went to the Wade archive for C.S. Lewis this past summer. I didn’t know what I would find, and when I got there the project I had proposed pretty much fell flat. But as I began to work in the archive, as I handled unknown letters and obsolete drafts and long-forgotten manuscripts, I got the bug. I found something interesting, ideas crashed together in my mental universe, and I soon found I was on a journey of discovery, sleuthing like a detective through historical obscurities as I collected clues until I began to form a picture of “what really happened.” Once you have this bug, you will find it almost incurable.

It was by instinct that I went to the Wade archive for C.S. Lewis this past summer. I didn’t know what I would find, and when I got there the project I had proposed pretty much fell flat. But as I began to work in the archive, as I handled unknown letters and obsolete drafts and long-forgotten manuscripts, I got the bug. I found something interesting, ideas crashed together in my mental universe, and I soon found I was on a journey of discovery, sleuthing like a detective through historical obscurities as I collected clues until I began to form a picture of “what really happened.” Once you have this bug, you will find it almost incurable.

It is precisely this kind of process that led Dr. Charlie W. Starr, professor of English at Kentucky Christian University, to his new book, Light: C.S. Lewis’s First and Final Short Story.  In 2010 he read the handwritten manuscript of a lost C.S. Lewis story and soon found himself drawn in to an intellectual journey through an historical mystery.

In 2010 he read the handwritten manuscript of a lost C.S. Lewis story and soon found himself drawn in to an intellectual journey through an historical mystery.

I have talked here about C.S. Lewis’ short story, “Light,” which is a version of “The Man Born Blind” (1977). Both extant versions of the story emerged in mysterious circumstances. “The Man Born Blind” was saved from a bonfire and kept secret for fifteen years; “Light” was unknown previous to the mid-1980s, when it appeared to a British bookseller and subsequently sold to American collector Dr. Edwin Brown, who donated it to the Lewis and Inklings collection at Taylor University. Light: C.S. Lewis’s First and Final Short Story is the result of Starr’s detective work in this intriguing mystery.

Light consists of three different movements. First, Starr publishes (for the first time, I believe), the entire short story, “Light,” as it appears in the Brown manuscript. He not only publishes a polished, final text, however, but also gives a parallel publication of “The Man Born Blind”—the first version of this story, he argues—next to “Light,” with all of the revisions in between. The result is that we can  see the process of how “The Man Born Blind,” possibly a revision of a much earlier story, becomes “Light” through a series of stylistic changes. Starr draws attention to these revisions in extensive footnotes and a summary chapter, and makes a convincing case that Lewis’ revisions not only produced a smoother story, but drew attention to a particular theme.

see the process of how “The Man Born Blind,” possibly a revision of a much earlier story, becomes “Light” through a series of stylistic changes. Starr draws attention to these revisions in extensive footnotes and a summary chapter, and makes a convincing case that Lewis’ revisions not only produced a smoother story, but drew attention to a particular theme.

Second, Starr offers us the entire story of how the manuscripts appeared, the processes of their authentication, and the possible solutions to a dozen problems that dominate the mystery. Not all questions are answered, but Starr—schooling himself in historical detective work as he goes—helps us understand Lewis’ writing process by looking at how he wrote in notebooks, the kinds of pens and inks he used, the development of his handwriting style, and even how he sketched out story outlines, revised poems, and made essay and lecture notes. In this section he, quite convincingly dates “The Man Born Blind” to 1944 or the first half of 1945, with “Light” following not long after. Beyond the sheer nerd-ness in this section—my favourite section!—Starr’s work offers us tentative templates with which to undertake an extensive process of dating Lewis’ manuscripts.

Third, Starr undertakes an interpretation of the short story. I believe this is the first substantial reading of “The Man Born Blind” that takes into account “Light,” even though the Brown manuscript of “Light” has been available at Taylor University for years. What is intriguing about Starr’s work is that he does not offer a single, integrated interpretation of “Light,” but looks at it from a number of angles, including Lewis’ discussions with Owen Barfield (for whom the original story may have been written), Lewis’ theories of how we know what we know (epistemology), and Lewis’ central idea of “longing,” which he variously calls “joy” or “sehnsucht.” In the end,  Starr argues, this short story draws our attention to the theme of “light”—a concept in Lewis that, though often forgotten, is absolutely central to his work. Starr’s reading of “Light” within Lewis’ writings draws together the various sermons, stories, and essays into a coherent whole.

Starr argues, this short story draws our attention to the theme of “light”—a concept in Lewis that, though often forgotten, is absolutely central to his work. Starr’s reading of “Light” within Lewis’ writings draws together the various sermons, stories, and essays into a coherent whole.

The first two movements are important from an historical perspective and add much to Lewis scholarship. They are also a lot of fun, which is why they were the focus of his lecture at the Frances White Ewbank Colloquium at Taylor University in June and in his interview with William O’Flaherty. I think, though, that the third movement is actually his most important work. If the picture Starr paints of Lewis’ epistemology is accurate, it means a reorientation of how we understand Lewis’ philosophical standpoint. Starr admits to his tentative conclusions about the difficult—and admittedly strange—story that is “A Man Born Blind”/”Light,” but if he is correct in his interpretation, “light” is a theme that is worth further consideration. I wonder sometimes if Starr takes Lewis’ Platonic starting point too far. I am not yet qualified to offer a substantial critique, but I felt less secure of Starr’s reading of Lewis in this particular area.

Anyone who reads this book is going to have to accept the piebald nature of the work. Light has two audiences—C.S. Lewis fans and literary scholars—and thus has two very different voices, each used variously throughout. In the introduction and the second movement, where Starr describes the story of the lost and found manuscripts, he is naturally very casual in his approach, telling the detective story much as he would tell it to a friend. He also takes this casual tone in the footnotes to his parallel publication of the story revisions. The casual tone and accessible language highlight the jarring difference in the academic tone in the other chapters of the book, mainly the third movement (interpretation) and in the technical description of the manuscripts.

the jarring difference in the academic tone in the other chapters of the book, mainly the third movement (interpretation) and in the technical description of the manuscripts.

I would encourage the potential reader not to be fooled by these shifts in tone. A narrative voice in parts is not an indication of a lack of scholarship. The book is footnoted well throughout, and the interpretive section is up to the standard of academic discourse. I think the tone, personally, is a little too casual, but the fun-to-read sections will suit part of that target audience well.

While an excellent book overall, Starr’s work is not without fault. I’d like to highlight two areas of concern—both missed opportunities more than hardcore critiques—and ask a question that comes out of a third concern.

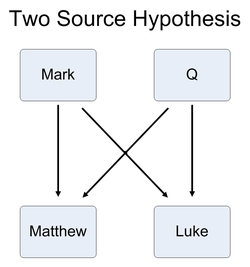

One blemish in an otherwise skillful book is Charlie Starr’s treatment of “redaction criticism.” Redaction criticism is a method of literary study that looks at how authors shape the various sources they use when they are writing. It is often used in biblical studies, and might ask why there are two Creation stories (Genesis 1-2) or two Noah stories (Genesis 6-8) or two different Sermons of Jesus on the Mount or Plain (Matthew 5-7 and Luke 6). As we study the gospels, it seems like Mark is the oldest, and that Matthew and Luke use Mark as a source—Luke specifically says he has used good sources (1:1-4), and they both copy Mark word for word in many places, making only minor changes in others.

There are places, though, that Matthew and Luke share material that Mark doesn’t have—like the Sermon on the Mount/Plain. Where did that material come from? Matthew was a disciple, so he may have  witnessed it, but Luke wasn’t. Either Luke copied Matthew—which doesn’t seem likely—or they both used another source in their research, a source we no longer have. Bible scholars call that source “Q,” and while there is speculative and unhelpful work in this field, and while we argue over what Q was like and whether it was a written document or an oral tradition or even a number of sources, we mostly agree that it is a logical necessity.

witnessed it, but Luke wasn’t. Either Luke copied Matthew—which doesn’t seem likely—or they both used another source in their research, a source we no longer have. Bible scholars call that source “Q,” and while there is speculative and unhelpful work in this field, and while we argue over what Q was like and whether it was a written document or an oral tradition or even a number of sources, we mostly agree that it is a logical necessity.

Starr, however, launches into this world of biblical literary criticism with unrestrained disdain. “By the beginning of summer, 2011, an idea was creeping into my head which I did my best to keep from taking seriously” (33). This idea is that there may be a Q-like document for the “Light” story. Considering this idea, Starr admits that “I’m not a biblical scholar.” (33), but that the “Q” hypothesis is a “crack pot” theory.

Quite apart from Q being a “crack pot” idea, a Q document for this short story is a really intriguing hypothesis. We have two extant documents: “The Man Born Blind” (MBB) and “Light,” both from WWII (1944-45), with evidence there was also a story from the late 1920s. If that is the case, we have, by logical necessity, two basic options:

- Lewis wrote the WWII-story based on his memory of the 1920s story.

- Lewis revised the WWII-era story from a draft of his 1920s story.

There may also be a draft between the 1920s and WWII editions.

If #2 is the case, that Lewis is revising an older story, we have three basic options:

- Older story → MBB → Light

- Older story → Light → MBB

- Both Light and MBB use the same older version in different ways

Option #3 is the “Q” option. It is an important theoretical option for MBB/Light as it is for the gospels. I think that Starr could have made greater mileage in this area if he had seriously presented this option, worked through the background, and considered all the ramifications. As it turns out, I think that Starr has conclusively demonstrated that MBB is a previous generation of “Light,” so if there was an earlier story, then “The Man Born Blind” came from that story, and was revised into “Light.”

My second critique has to do with the allegation of forgery “in the late 80s” (1) that is hinted at but not dealt with directly. Starr notes that Kathryn Lindskoog levels the charge and that her arguments have been “thoroughly refuted” (20). Starr is exceptionally detailed in his footnotes, leaving trails for academics to follow and new  paths for fans to explore. On this point, however, Starr is surprisingly vague: he does not say here where Lindskoog makes her claims, or where she has been refuted. He also fails to mention that literally dozens of Lewis scholars, writers, and academics participated in the charge of forgery. These are strange lacunae in an otherwise tight book.

paths for fans to explore. On this point, however, Starr is surprisingly vague: he does not say here where Lindskoog makes her claims, or where she has been refuted. He also fails to mention that literally dozens of Lewis scholars, writers, and academics participated in the charge of forgery. These are strange lacunae in an otherwise tight book.

I am relatively new to the C.S. Lewis studies world, but one thing that I have picked up is general distaste for Lindskoog’s work among many people involved in the conversation. I suspect that Charlie Starr shares that distaste and thus has relegated the forgery conversation to a vague footnote. I have no concern to defend her here, but to point out that in skipping over this key aspect of the manuscript history, Starr misses an opportunity to strike a blow at the heart of Lindskoog’s claims.

Dr. Starr has convincingly shown that these manuscripts are indeed not forgeries. In the case of “The Man Born Blind,” it is written in Lewis’ handwriting, using the character of pen and kind of ink Lewis used, and is preceded and followed in a bound notebook by pre-published material found in various parts of Lewis’ corpus. Moreover, the revisions in the manuscript are suggestive of the “Light” manuscript which surfaces some years later. While a forgery is still faintly possible, the extensive nature of the hoax is just  so elaborate that it pushes us beyond reasonable doubt. Skipping the Lindskoog claim, and using the hyperbolic “thoroughly refuted”—I know of no response to the claim of one of those at the bonfire that it never happened, for example—and Starr misses a key opportunity.

so elaborate that it pushes us beyond reasonable doubt. Skipping the Lindskoog claim, and using the hyperbolic “thoroughly refuted”—I know of no response to the claim of one of those at the bonfire that it never happened, for example—and Starr misses a key opportunity.

This second critique leads to a question that puzzles and intrigues me: in a mystery involving hidden and found manuscripts and claims of forgery, is it problematic to include at the heart of the investigation the person who found the manuscript and is the target of the charge of forgery? Walter Hooper, lifelong literary executor of Lewis’ estate and compiler-author of so many key Lewis resources, was the one who rescued the MBB manuscript from the flames, kept it quiet for fifteen years, and then published it in 1977. And it is Walter Hooper who is the mark for Kathryn Lindskoog’s accusations of forgery. Yet Hooper is absolutely key to Starr’s investigation, as he critiques Starr’s conclusions and offers suggestions in person and by email. Does this kind inquiry require more distance than Starr gave it?

It is a genuine question. One of my issues with offering critique within C.S. Lewis studies is how connected everyone is. Walter Hooper has even been kind enough to help me along the way, and I’ve sat at the same dinner table as Charlie Starr—though the roast beast was more memorable than anything I said, I’m sure. My critiques in this review are pretty minor: one thing that Starr chose to leave out, and another he chose not to take seriously—both at his own peril, I believe. I suspect that Charlie Starr will be okay with whatever critique I offer, and may even respond, but I feel implicated within an international circle of scholars that is at once extremely helpful and concurrently limiting. I am used to a more detached and much more  challenging academic environment. I leave the question open, if anyone can enlighten me.

challenging academic environment. I leave the question open, if anyone can enlighten me.

Minor criticisms and my ponderous question aside, Light: C.S. Lewis’s First and Final Short Story is a great book. It is academically rigorous, offers interpretive suggestions that may challenge our understanding of Lewis’ work, and gives us tools to engage in a large-scale reconsideration of Lewis’ manuscripts, writing processes, and development of thought. It is an absolutely essential book.

More than that, it is a lot of fun to read. The bifurcated nature of the writing may cause fans to stumble a bit in the epistemological conversation, but hard-won paths are typically worth the climb. To me, Light: C.S. Lewis’s First and Final Short Story by Dr. Charlie Starr is one of the necessary Lewis volumes of the year. A word of fair warning though: this book is likely to expose in certain readers that inclination to Lewis geekery and archival mysteries that has infected me and Charlie Starr and myriads of others. Ignore this caution at your own peril.

This is an excellent review. You have balanced your positive examination nicely with a couple of thoughtful critiques, and you have revealed your own scholarly acuity throughout. I look forward to reading this book — and I hope Charlie responds, prompting a discussion of the excellent points you raise.

You are right about the small, inbred nature of Lewis studies. Usually that cozy, familial circle is a healthy environment for good scholarship, collaboration, discovery, accountability, information-sharing, and all the other positive aspects of community. Occasionally, however, and on certain topics (i.e., Lindskoog), it does become insular and possibly even somewhat suffocating. I think younger scholars like ourselves should learn a lesson from this kind of hush-hush insider attitude and make sure we open those locked doors, respectfully, and critique what’s behind them.

It’s also time for more rigourous application of theoretical analysis to CSL’s works, and the kind of close textual detective work that Charlie (and you) are doing is a great step in the right direction.

Thanks for the response, Sørina. Charlie’s book is quite good, and brings together the two streams you mention (critical and historical). You are the critic, so you can perhaps judge his critical approach best.

Here’s the ticket: “open those locked doors, respectfully, and critique what’s behind them”. I think that the “locked doors” threatens both of the streams of scholarship that will dominate the new generation of Inklings scholarship.

Pingback: The Surprising Danger of Light | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: The Society of Tim | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: The Difference Between Pressure & Discipline: My Reflection on my 100th Post | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: A Year of Reading | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Adventures in Lewisiana | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Truth Claims ≠ Violence | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: False Starts and Missteps: How C.S. Lewis Found his Literary Voice (#WritingWednesdays) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Wow, What a Fall! | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Leuven to Chester in 12 Hours (Live Tweeting Adventure) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: A Guide to Doing C.S. Lewis Research at the Bodleian: From One Who Started Badly | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: 2014: A Year of Reading | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: What I’m Reading Wednesday | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Just a note Brenton. We are very thankful for Dr. Ed Brown, but he did not donate his collection (which included the LIGHT manuscript) to Taylor University. I’m the Director of the Center for the Study of C. S. Lewis and Friends which is built around the Brown Collection. I enjoyed your piece. I agree that Q is not a crack pot theory.

Thanks Joe. It was good to meet you at Taylor. It was also one of the first libraries I’ve been in that had a British bar. Perhaps that’s better than coffee shops in libraries!

I had forgotten I wrote that here and can adjust it. But the time I wrote this blog about Dr. Brown (http://apilgriminnarnia.com/2014/04/07/adventures-in-lewisiana/), I obfuscated my language, suspecting it wasn’t just a donation. I said:

“He began collecting nearly fifty years ago, and about fifteen years ago provided his collection to The Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends in the Zondervan Library at Taylor University in Upland, IN.”

Is that a fair statement?

Cheers,

Brenton

Pingback: Why Didn’t Someone See it First? Discussing the Screwtape-Ransom Discovery | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: 2015: A Year in Books | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Reconsidering the Lindskoog Affair | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Yatta! Chronological Reading of C.S. Lewis Complete | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: How You Can Read C.S. Lewis Chronologically | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: C.S. Lewis Manuscript Collections and Reading Rooms | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: The Lost-But-Found Works of C.S. Lewis | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Photographic Plates of C.S. Lewis’ Manuscripts and Letters | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: To C.S. Lewis Readers and Researchers: A Call for Literary Links | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: What Art is For: With C.S. Lewis and Dr. Charlie Starr | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: 2016: A Year of Reading | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “In and Out of the Moon” by Jeff McInnis | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: C.S. Lewis’ Christmas Sermon for Pagans (Friday Feature) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Call for Papers: 2018 C.S. Lewis & Friends Colloquium at Taylor University | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: 2018: A Year of Reading: The Nerd Bit | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: More Relevant Than Ever: Why the Wade Center Authors Like Lewis and Tolkien Still Matter (Friday Feature) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Free Event Today: A Sehnsucht Digital Tea at the C. S. Lewis and Friends Center | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: My Paper, “A Cosmic Shift in The Screwtape Letters,” Published in Mythlore | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: 2020: A Year of Reading: The Nerd Bit, with Charts | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Why is Tolkien Scholarship Stronger than Lewis Scholarship? Part 1: Creative Breaks that Inspired Tolkien Readers | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Good C.S. Lewis Studies Books That Did Not Win the Mythopoeic Award: Part 1: C.S. Lewis on Theology, Philosophy, and Spiritual Life | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Good C.S. Lewis Studies Books That Did Not Win the Mythopoeic Award: Part 3: Literary Studies on C.S. Lewis | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: The C.S. Lewis Studies Series: Where It’s Going and How You Can Contribute | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: A Thing of Forms Unknown: Thoughts on C.S. Lewis and Horror with Chris Calderon (Happy Hallowe’en!) | A Pilgrim in Narnia