At A Pilgrim in Narnia we have an occasional feature called “Throwback Thursday.” This is where I find a blog post from the past–raiding either my own blog-hoard or someone else’s–and throw it back out into the digital world. This might be an idea or book that is now relevant again, or a concept I’d like to think about more, or even “an oldie but a goodie” that I think needs a bit of spin time.

At A Pilgrim in Narnia we have an occasional feature called “Throwback Thursday.” This is where I find a blog post from the past–raiding either my own blog-hoard or someone else’s–and throw it back out into the digital world. This might be an idea or book that is now relevant again, or a concept I’d like to think about more, or even “an oldie but a goodie” that I think needs a bit of spin time.

For today’s Throwback Thursday, I am publishing here for the first time a close-reading article I wrote for Sørina Higgins’ Charles Williams-centred blog, “The Oddest Inkling.” I know that Charles Williams’ poetry is difficult to read–really, almost impossible to get your fingers around. And although I’m not a particularly sharp poetry reader, I have come to love his Arthurian poems as they have been curated and commented upon by C.S. Lewis in a 1947 collection, and as David Llewellyn Dodds has collected them. It took me time to find a rhythm in reading Williams, and I had to sort of “trust the text” to lead me there, without worrying terribly about understanding everything.

This piece is a longer literary-critical reflection on “The Son of Lancelot.” I had some notes written when I first read Taliessin through Logres in winter 2015, and Sørina’s call for papers gave me a chance to write out my thoughts. Here I reflect on Williams’ Arthuriad as Jewish Apocalypse, and then go to the other (shorter!) pieces to see the varied and complex ways that readers respond to his poetry. I came back to this piece in spring 2019 when I did a paper on Bird Box and Jewish apocalypse, and I taught this poem in a local literature class this winter. I have included a series note at the bottom, as well as the full poem–which is longish (10 pages). If I have made a transcription error, please let me know.

I was relieved when I came to this first line of Charles Williams’ “The Son of Lancelot”:

The Lupercalia danced on the Palatine

I only had to look up two of the words. I’m pretty good with prepositions (on) and articles (the), though it’s true that Williams might have some obscure layering in even a simple word like “dance.” I’m left with these two to look up: Lupercalia. Palatine.

I can guess that “Lupercalia” has to do with wolves—remember Professor Remus Lupin, protector of Harry Potter. Given the context I would guess “wolf dance” for Lupercalia, and I would be close to right. Whenever I see a word like Palatine I assume it is some sort of architectural term; I can never keep the architectural terms straight, which kept my career in biblical archaeology to a short five minutes in length.

I am, in fact, pretty close on both points. Palatine is one of the Seven Hills of Rome, a place my wife occasionally reminds me I have yet to take her. We get the architectural term “palace” from this very hill (and, no, I haven’t taken her to any palaces either). The name “Palatine” is an old pre-Tuscan word for the heavens, which is itself an architectural concept to the ancients. It was here in Palatine,  in a little cave, that the twin brothers of Rome were birthed and raised by a wolf. The brothers, Romulus and Remus—see the Harry Potter connection: do you think this sort of thing happens by accident?—fought for the throne, and it is Romulus whose name we recount as the patron of Rome. But both boys are remembered in the Roman festival called Lupercalia, where worshippers dance at the foot of Palatine Hill to the wolf god (whom we may know as Pan).

in a little cave, that the twin brothers of Rome were birthed and raised by a wolf. The brothers, Romulus and Remus—see the Harry Potter connection: do you think this sort of thing happens by accident?—fought for the throne, and it is Romulus whose name we recount as the patron of Rome. But both boys are remembered in the Roman festival called Lupercalia, where worshippers dance at the foot of Palatine Hill to the wolf god (whom we may know as Pan).

Now that I know those two key words, the line comes into focus.

Rather than leaping to conclusions and missing some salient point, though, I pause to look up the word “dance” in the Online Dictionary of Etymology. Though the history is uncertain, it probably two-steps back to the Old Frisian dintje, which has ecstatic religious connotations. Even here, Williams finds more to pack into a few words then most have in entire poems.

I have read through Williams’ Arthurian poems twice—once with the aid of C.S. Lewis as a commentator, and once with David Llewellyn Dodds, who also supplements the Lewis-Williams volume with some previously unpublished pieces. Each read-through was too quick: I could well have spent as much time on each stanza as I did on just this first line. Look how the stanza continues:

The Lupercalia danced on the Palatine

among women thrusting under the thong; vicars

of Rhea Silvia, vestal, Æneid, Mars-seeded,

mother of Rome; they exulted in the wolf-month.

The Pope’s eyes were glazed with terror of the Mass;

his voice shook on Lateran, saying the Confiteor.

Over Europe and beyond Camelot the wolves ranged.

It would be never-ending to chase Williams from word to word. Now that I know what Lupercalia and Palatine are, I see what vicars (priests) of Rhea Silvia (the mother of Romulus and Remus) means. Is “vestal” referring to the Roman goddess of the sacred fire? If so, we see Virgil as the mythologian of Rome, whose seedbed is myth and war and brutality (in both senses of the word, wolf-born and battle-ready).

It would be never-ending to chase Williams from word to word. Now that I know what Lupercalia and Palatine are, I see what vicars (priests) of Rhea Silvia (the mother of Romulus and Remus) means. Is “vestal” referring to the Roman goddess of the sacred fire? If so, we see Virgil as the mythologian of Rome, whose seedbed is myth and war and brutality (in both senses of the word, wolf-born and battle-ready).

Then we see the Pope: a spiritual shift as the geographical centre remains the same. What an image of the Pope! He is filled with terror as he says “I confess” (Confiteor), his voice shaking on Lateran. Is that an architectural reference to the palaces and Basilica that sit on the hill opposing Palatine? Or is it the Lateran councils, of which there were many? Williams would have been attracted to Lateran IV (1215), which confirmed the doctrine of transubstantiation in the Mass—a key aspect of Williams’ Grail imagery. Or it could be both: material and trans-material reality caught up in the same incarnational image.

In any case, we see that despite the Christian supersession of Rome, wolves still call out in the night across Europe, all the way to Camelot in the North, which is the court of Arthurian romance and the bishopric of romantic love.

I wrote in the margin next to this first stanza: “so evocative, even when I don’t know all the references.” Even in this exegesis, I am likely missing something, and all of Charles Williams’ hundreds of pages of poetry could be treated in the same way. To do justice we must walk word by word, and into the woods of many words behind each word. How do I treat “The Son of Lancelot” in a single blog?

I will have to latch onto one of the individual threads and tug on it. In doing so I am leaving behind architecture, geography, liturgy, the cross and the crescent, the physicks and mysticks, and colour. I am also leaving behind the ways in which Williams plays with the Arthurian canon, trusting that others in the series will pick this idea up.

Instead, I will look at one idea and inadequately suggest a context for Williamsian intertextuality in this poem.

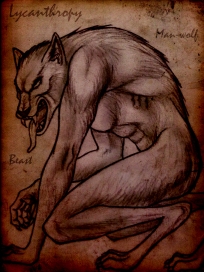

The Son of Lancelot” is, I think, an elegantly beastly poem, a poem that plays with the double meaning of brutality.

Let’s begin with the story as best we can discern it, for the story is not too unlike Malory’s account of Lancelot. The great knight Lancelot on quest comes to a castle near Carbonek. Deceived by magic, he mistakes Helayne, the daughter of Pelles, for his lady, Guinevere. They make love through the night and the lovers fall asleep in one another’s arms. When Lancelot turns in the morning light to see his lady, it is another woman in his arms. He has betrayed Guinevere and is cut off from her grace. Filled with grief, Lancelot leaps from Helayne’s window and flees to the wilderness as a madman. He finds himself in Broceliande which, as Lewis puts it so neatly, is the place that “leads down to the world of D.H. Lawrence as well as up to the world of Blake: the soul that enters it will be likely to ‘grow backward’” (343).

I don’t remember reading Malory and feeling the Lenten, wintery feel of Williams’ poem. Yet the seasons are key as we move toward Easter and restoration. And in Malory, we see that someone tends to the madman Lancelot, naked and barbaric as he is in his form. In Williams’ poem, there is no care for the lycanthropic beast-man. In Williams, Lancelot in wolf form threatens to devour the child that is born to Helayne, the young Galahad. Merlin, whose role we will discuss in a moment, transforms himself into wolf form and stands against Lancelot. The wolf-Lancelot defeated, Merlin takes the messianic child to safety. Lancelot, by

I don’t remember reading Malory and feeling the Lenten, wintery feel of Williams’ poem. Yet the seasons are key as we move toward Easter and restoration. And in Malory, we see that someone tends to the madman Lancelot, naked and barbaric as he is in his form. In Williams’ poem, there is no care for the lycanthropic beast-man. In Williams, Lancelot in wolf form threatens to devour the child that is born to Helayne, the young Galahad. Merlin, whose role we will discuss in a moment, transforms himself into wolf form and stands against Lancelot. The wolf-Lancelot defeated, Merlin takes the messianic child to safety. Lancelot, by

… the fire built in Carbonek’s guest-chamber

… lay tended, housed and a man,

to be by Easter healed and horsed for Logres; (80-81)

Lent is over, the winter breaks into spring. The child is safe, and Lancelot is whole again for resurrection Sunday.

Between the story and the lyrics, there is a great, rich store of Williamsian imagistic play. What I want to highlight is the apocalyptic backdrop of the poem: if I as a modern reader struggle to recover the classical references in Williams’ poetry, most of our generation is likely to miss the biblical framework Williams uses in “The Son of Lancelot.”

Knowing what people mean when they say “apocalypse” today will not help. Apocalypse is a genre of Jewish literature that emerged in the last few centuries as Jews looked forward to the coming of Messiah. It is a complex, multi-layered genre that combines prophetic and wisdom literature to create a new “images”—metaphors, symbols, and sometimes allegories that invest Israel’s story with theological significance.

In “The Apocalypse of Abraham” for example, we see the story of Abraham sacrificing Isaac on the mountain. The story is the same, yet the imagery changes. Following a forty-day fast (think Israel in the desert), an angel comes to discourse with Abraham. The angel heightens Abraham’s view, pulling back the camera angle on the scene, so that Abraham sees not only the prepared sacrificial lamb that he is missing, but a parade of creatures that prefigure the salvation history of Israel. Then the vision ends with Abraham ascending on wings of a bird, so that Abraham

may be able to see in heaven, and [look] upon earth, and in the sea, and in the abyss, and in the under-world, and in the Garden of Eden, and in its rivers, and in the fullness of the whole world and its circle – you shall gaze into them all (12:10).

At first, the camera is in tight looking at the literal, physical scene, the walk of the faithful father to the dreaded altar. Then the camera pulls back to show Abraham in Israel’s history (both the past and the future). Then, finally, the camera pulls back all the way to the cosmic view—looking at Israel in terms of her entire mythological framework. We see the literal, the spiritual, and the mythic all bound up in the same Apocalyptic peak.

The features that are in this tiny Apocalypse are in all apocalyptic literature: mythic and symbolic language, angel-mediators of revelation, a response to difficulty or oppression, a cosmic view of history, and hope—all bound up in biblical imagery that is filled with symbolism. It is not about “the end of the world,” but it might be about the end of an age and the birth of a new one. Some of our messianic literature fits in here.

We see in the poem that Charles Williams uses Apocalypse as a genre rather deftly.

Merlin is the angel-mediator, with Providence as the spiritual reality of God in the background. Merlin is the only one who is able to see the action at the three levels of literal, historical-spiritual, and cosmic-mythic, and we are invited (like Abraham) to rise to the heavens to see the story of Galahad’s birth in its true significance. As Lewis says, “Merlin has risen to where he sees things from the point of view of the third Heavenly sphere” (345).

Merlin is the angel-mediator, with Providence as the spiritual reality of God in the background. Merlin is the only one who is able to see the action at the three levels of literal, historical-spiritual, and cosmic-mythic, and we are invited (like Abraham) to rise to the heavens to see the story of Galahad’s birth in its true significance. As Lewis says, “Merlin has risen to where he sees things from the point of view of the third Heavenly sphere” (345).

On the physical-literal level, we have the story of Lancelot’s failure and the war of cross and crescent. With this level of knowledge in place for the reader,

Merlin grew rigid; down the implacable hazel

(a scar on a slave, a verse in Virgil, the reach

of an arm to a sickle, love’s means to love)

he sent his hearing into the third sphere—

once by a northern poet beyond Snowdon

seen at the rising of the moon, the mens sensitiva,

the feeling intellect, the prime and vital principle,

the pattern in heaven of Nimue, time’s mother on earth,

Broceliande. Convection’s tides cease

there, temperature is steady to all tenderness

in the last reach of the hazel; fixed is the full.

He knew distinction in three abstractions of sound,

the women’s cry under the thong of Lupercal,

the Pope’s voice singing the Glory on Lateran,

the howl of a wolf in the coast of Broceliande.

The notes of Lupercal and Lateran ceased; fast

Merlin followed his hearing down the wolf’s howl

back into sight’s tritosphere—thence was Carbonek

prodigiously besieged by a feral famine; a single

wolf, grey and gaunt, that had been Lancelot,

imbruted, watching the dark unwardened arch,

crouched on the frozen snow beyond Broceliande.

We see here the “tritosphere”—the literal, spiritual, and mythic—all caught up in Merlin’s apocalyptic view. This is all happening at the same moment that King Pelles has received the Dolorous Stroke, bleeding as a woman menstruating (“his flesh from dawn-star to noontide day / by day ran as a woman’s under the moon”). The moon imagery is not insignificant to wolf tales, and here Merlin views woman’s menstruation in the same mytho-moment as Lancelot’s breaking Helayne’s hymen and Pelles’ fateful wound.

As Lancelot flees his betrayal of Guinevere, “he grew backward all summer, laired in the heavy wood.” Lancelot is now, as wolf-man, “a foe by the women’s well.” But, of course, in the logic of Apocalypse, he has become what he already is. Like Eustace becoming a dragon while thinking draconian thoughts (remember Rowling’s play with this image too), Lancelot becomes the beast that he is inside. Finally, as the bastard messianic child his born to begin a new age, we see that

what was left of the man’s contrarious mind

was twinned and twined with the beast’s bent to feed

Hungry, devoid entirely of humanity, “it”—not “he”—“crept to swallow the seed / of love’s ambiguity.” The child is in mortal danger and the new age threatens to fall just as it begins.

Remember that we have the cosmic view of things as readers, and we know the geopolitical context of Williams mytho-poetic Logres:

And infinite beyond him the whole Empire contracted

from (within in) wolves and (without it) Moslems.

And in the cosmic view of things wee see all the layers of literal, symbolic, and mythic in the child’s birth:

Helayne, Lancelot’s bed-fellow, felt her labour.

Brisen knelt; Merlin watched her hands;

the children of Nimue timed and spaced the birth….

Merlin from the hazel’s divination saw

the child lie in his sister’s hands; he saw

over the empire the lucid flash of all flesh,

shining white on the sullen white of the snow.

What follows this poetry are densely symbolic lyrics with deep, pathetic meaning. While Lancelot is lost to animality, Merlin is able to take up Lupercal’s form to save the child, thus uniting (in Williams’ mind) Lupercal and Lateran, the two hills of Rome, Carbonek and Camelot. The child cries, “his wail was a song and a sound in the third heaven,” and the wolves crash, flesh against flesh, a maddening heap of snarling teeth and claws. But the emaciated man-wolf is no match for the magician. After a brief canine joust, Lancelot falls and lays senseless in lupine shade. Thus, “warm on a wolf’s back, the High Prince rode into Logres.”

It is not difficult to see the messianic imagery in the poem. Galahad, the “Merciful Child,” is protected by the nuns of Blanchefleur until his time might come and the new age is inaugerated. And like the Christ-child of old or the Nativity of Harry Potter sleeping in “crimson wrappings” or “swaddling clothes,” the moment of birth is filled with meaning beyond the physical. We know the Nativity stories repeated each Christmas, but we often miss the Nativity of Revelation 12.

It is not difficult to see the messianic imagery in the poem. Galahad, the “Merciful Child,” is protected by the nuns of Blanchefleur until his time might come and the new age is inaugerated. And like the Christ-child of old or the Nativity of Harry Potter sleeping in “crimson wrappings” or “swaddling clothes,” the moment of birth is filled with meaning beyond the physical. We know the Nativity stories repeated each Christmas, but we often miss the Nativity of Revelation 12.

This book, the Apocalypse, does what all Jewish Apocalypse does: by the aid of a mediator, we are risen to a cosmic view so we can see the true significance of history through mythic-spiritual symbolism. So we see the Nativity from a cosmic angle in Rev 12:

12:1 A great sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars on her head. 2 She was pregnant and cried out in pain as she was about to give birth. 3 Then another sign appeared in heaven: an enormous red dragon with seven heads and ten horns and seven crowns on its heads. 4 Its tail swept a third of the stars out of the sky and flung them to the earth. The dragon stood in front of the woman who was about to give birth, so that it might devour her child the moment he was born. 5 She gave birth to a son, a male child, who “will rule all the nations with an iron scepter.” And her child was snatched up to God and to his throne. 6 The woman fled into the wilderness to a place prepared for her by God, where she might be taken care of for 1,260 days.

7 Then war broke out in heaven. Michael and his angels fought against the dragon, and the dragon and his angels fought back. 8 But he was not strong enough, and they lost their place in heaven. 9 The great dragon was hurled down….

We see how Charles Williams echoes the Apocalyptic significance of the Nativity in his Galahad myth, but also how he copies some of the elements of the Apocalypse form.

Beyond the form of Apocalypse and the Nativity of Galahad-Christ, the figure of Lancelot and the Lycanthropy find their root in Jewish Apocalypse. While I will not dwell there, you can see what I mean when you turn to Daniel 12 and read about the dream of King Nebuchadnezzar. Because he was proud, and despite the warning of the Hebrew seer, we see that Nebuchadnezzar, to use Williams’ words, “grew backward” until he was “laired in the heavy wood.” In Daniel’s language,

His body was drenched with the dew of heaven until his hair grew like the feathers of an eagle and his nails like the claws of a bird (4:33).

Finally, when the time was full, Nebuchadnezzar raised his eyes to heaven and his sanity was restored. Within the narrative logic of Daniel, we see this is where the book moves from the history of the exiles to Apocalypse, also beginning to move from prose to poetry. Throughout the book of Daniel, beastliness remains a theme, so that it is very much the case that the insides and the outsides of the human soul-body begin to entwine, as they have in Lancelot. In both Daniel’s Babylon and Williams’ Logres, it remains to be seen whether the empires will be beastly or humane.

Finally, when the time was full, Nebuchadnezzar raised his eyes to heaven and his sanity was restored. Within the narrative logic of Daniel, we see this is where the book moves from the history of the exiles to Apocalypse, also beginning to move from prose to poetry. Throughout the book of Daniel, beastliness remains a theme, so that it is very much the case that the insides and the outsides of the human soul-body begin to entwine, as they have in Lancelot. In both Daniel’s Babylon and Williams’ Logres, it remains to be seen whether the empires will be beastly or humane.

Nebuchadnezzar’s beast-beard dripping with dew, Lancelot crouched on the frozen snow beyond Broceliande, the dragon crouching to devour the child upon its birth, the wolf-man

Slavering he crouched by the dark arch of Carbonek,

head-high howling, lusting for food, living

for flesh, a child’s flesh, his son’s flesh.

It is poignant imagery. In Williams’ Arthurian Apocalypse we see his direst warnings of the mytho-prophetic danger of sin—of the animal heart in all of us that, left untamed, that threatens to overtake the man or the kingdom. I cannot help wondering to what degree Williams himself understood his own heart. He certainly believed of himself that his actions had the tritospheric realities of the literal, the spiritual, and the mythic.

Series Introduction

Sørina Higgins is a leading Charles Williams critic, modernist scholar, curator of the Oddest Inkling blog, and editor of The Chapel of the Thorn, an unpublished Charles Williams play from 1912. From time to time she recruits a number of guest writers to do a series, including one on each of the poems in Williams’ Arthurian book, Taliessin through Logres.

Sørina Higgins is a leading Charles Williams critic, modernist scholar, curator of the Oddest Inkling blog, and editor of The Chapel of the Thorn, an unpublished Charles Williams play from 1912. From time to time she recruits a number of guest writers to do a series, including one on each of the poems in Williams’ Arthurian book, Taliessin through Logres.

If it wasn’t for C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams may have been in some danger of being a forgotten poet. His work is obscure, a kind of inventive genius and perversity combined, where abstractions are literalized and symbols may be in danger of coming to life and devouring the characters (or the reader). And, yet, I think that Williams is worth reading on his own, so I appreciate the diverse and well-written series on Taliessin through Logres from back in 2016. The 24 poems are covered by students and scholars, exploring the themes in reflections, queries, and critical pieces.

The Son of Lancelot by Charles Williams

The Lupercalia danced on the Palatine

among women thrusting under the thong; vicars

of Rhea Silvia, vestal, Æneid, Mars-seeded,

mother of Rome; they exulted in the wolf-month.

The Pope’s eyes were glazed with terror of the Mass;

his voice shook on Lateran, saying the Confiteor.

Over Europe and beyond Camelot the wolves ranged.

Rods of divination between Lupercal and Lateran:

at the height of the thin night air of Quinquagesima,

in Camelot, in the chamber of union, Merlin dissolved

the window of horny sight on a magical ingress;

with the hazel of ceremony, fetched to his hand—cut,

smoothed, balsamed with spells, blessed with incision—

he struck from the body of air the anatomical

body of light; he illustrated the high grades.

In the first circle he saw Logres and Europe

sprinkled by the red glow of brute famine

in the packed eyes of forest-emerging wolves,

heaped fires in the villages, torches in towns,

lit for safety; flat, frozen, trapped

under desecrated parallels, clawed perceptions

denounced to a net of burning plunging eyes,

earth lay, at the knots the protective fires;

and he there, in his own point of Camelot,

of squat snow houses and huddled guards.

Along the print of the straight and sacred hazel

he sent his seeing into the second sphere:

to the images of accumulated distance, tidal figures

shaped at the variable climax of temperatures; the king

dreaming of a red Grail in an ivory Logres

set for wonder, and himself Byzantium’s rival

for men’s thuribled and throated worship—magic

throws no truck with dreams; the rod thrust by:

Taliessin beneath the candles reading from Bors

letters how the Moslem hunt in the Narrow Seas

altogether harried God and the soul out of flesh,

and plotting against the stresses of sea and air

the building of a fleet, and the burning blazon-royal

flying on a white field in the night—the hazel

drove, slowly humming, through spirals of speculation,

and Merlin saw, on the circle’s yonder edge,

Blanchefleur, Percivale’s sister, professed at Almesbury

to the nuns of infinite adoration, veiled

passions, sororal intellects, earth’s lambs,

wolves of the heavens, heat’s pallor’s secret

within and beyond cold’s pallor, fires

lit at Almesbury, at Verulam, at Canterbury, at Lateran,

and she the porter, she the contact of exchange.

Merlin grew rigid; down the implacable hazel

(a scar on a slave, a verse in Virgil, the reach

of an arm to a sickle, love’s means to love)

he sent his hearing into the third sphere—

once by a northern poet beyond Snowdon

seen at the rising of the moon, the mens sensitiva,

the feeling intellect, the prime and vital principle,

the pattern in heaven of Nimue, time’s mother on earth,

Broceliande. Convection’s tides cease

there, temperature is steady to all tenderness

in the last reach of the hazel; fixed is the full.

He knew distinction in three abstractions of sound,

the women’s cry under the thong of Lupercal,

the Pope’s voice singing the Glory on Lateran,

the howl of a wolf in the coast of Broceliande.

The notes of Lupercal and Lateran ceased; fast

Merlin followed his hearing down the wolf’s howl

back into sight’s tritosphere—thence was Carbonek

prodigiously besieged by a feral famine; a single

wolf, grey and gaunt, that had been Lancelot,

imbruted, watching the dark unwardened arch,

crouched on the frozen snow beyond Broceliande.

Pelles the Wounded King lay in Carbonek,

bound by the grating pain of the dolorous blow;

his flesh from dawn-star to noontide day by day

ran as a woman’s under the moon; in midsun

he called on the reckless heart of God and the Emperor;

he commended to them and commanded himself and his land.

Now in the wolf-month nine moons had waned

since Lancelot, ridden on a merciful errand, came

that night to the house; there, drugged and blurred

by the medicated drink of Brisen, Merlin’s sister,

he lay with the princess Helayne, supposed Guinevere.

In the morning he saw; he sprang from the tall window;

he ran into a delirium of lycanthropy; he grew

backward all summer, laired in the heavy wood.

In autumn King Pelles’ servants brought him news

of a shape glimpsed on the edge of Broceliande,

a fear in the forest, a foe by the women’s well.

Patient, the king constrained patience, and bade

wait until the destined mother’s pregnancy was done.

All the winter the wolf haunted the environs of Carbonek;

now what was left of the man’s contrarious mind

was twinned and twined with the beast’s bent to feed;

now it crept to swallow the seed

of love’s ambiguity, love’s taunt and truth.

Man, he hated; beast, he hungered; both

stretched his sabers and strained his throat; rumble

of memories of love in the gaunt belly told

his instinct only that something edible might come.

Slavering he crouched by the dark arch of Carbonek,

head-high howling, lusting for food, living

for flesh, a child’s flesh, his son’s flesh.

And infinite beyond him the whole Empire contracted

from (within in) wolves and (without it) Moslems.

The themes feel back round separate defensive fires;

there only warmth dilated; there they circled.

Caucasia was lost, Gaul was ravaged, Jerusalem

threatened; the crescent cut the Narrow Seas,

while from Cordovan pulpits the iconoclastic

heretical licentiates of Manes denounced union,

and only Lupercal and Lateran preserved Byzantium.

Helayne, Lancelot’s bed-fellow, felt her labour.

Brisen knelt; Merlin watched her hands;

the children of Nimue timed and spaced the birth.

Contraction and dilation seized the substance of joy,

the body of the princess, but in her stayed from terror,

from surplus of pain, from outrage, from the wolf in flesh,

such as racked in a cave the Mother of Lupercal

and now everywhere the dilating and contracting Empire.

The child slid into space, into Brisen’s hands.

Polished brown as hazel-nuts his eyes

opened on his foster-mother; he smiled at space.

Merlin from the hazel’s divination saw

the child lie in his sister’s hands; he saw

over the empire the lucid flash of all flesh,

shining white on the sullen white of the snow.

He ran down the hazel; he closed the window; he came

past the royal doors of dream, where Arthur, pleased

with the Grail cooped for gustation and God for his glory,

the æsthetic climax of Logres, softly slept;

but the queen’s tormented unæsthetic womanhood

alternately wept and woke, her sobs crushed

deep as the winter howls were high, her limbs

swathed by tentacles, her breasts sea-weighed.

Across the flat sea she saw Lancelot

walking, a grotesque back, the opposite of a face

looking backward like a face; she burst the swollen sea

shrieking his name; nor he turned nor looked,

but small on the level dwindled to a distant manikin,

the tinier the more terrible, the sole change

in her everlastingness, except, as Merlin passed,

once as time passed, the hoary waters

laughed backward in her mouth and drowned her tongue.

Through London-in-Logres Merlin came to the wall,

the soldiers saw him; their spears clapped.

For a blade’s flash he smiled and blessed their guard,

and went through the gate, beyond the stars’ spikes—

as beyond palisades to everywhere the plunging fires,

as from the mens sensitive, the immortal tenderness,

magically exhibited in the ceremonial arts,

to the raging eyes, the rearing bodies, the red

carnivorous violation of intellectual love,

and the frozen earth whereon they ran and starved.

Far as Lancelot’s dwindling back from the dumb

queen in a nightmare of the flat fleering ocean,

the soldiers saw him stand, and heard as if near—

far to sight, near to sound—the small

whistling breath in the thin air of Quinquagesima

of the incantation, the manner of the second working.

Then the tall form on the monstrous snow

dilated to monstrosity, swelling as if power

entered it visibly, from all points of the wide

sky of the wolf-month: the shape lurched and fell,

dropping on all fours, lurched and leapt and ran,

a loping terror, hurtling over the snow,

a giant white wolf, diminishing with distance,

till only to their aching eyes a white atom

spiraled wildly on the white earth, and at last

was lost; there the dark horizontal edge

of a forest closed their bleak world.

Between the copses on the coast of Broceliande

galloped the great beast, the fierce figure

of universal consumption, Lupercal and Lateran,

taunt of truth, love’s means to love

in the wolf-hour, as to each man in each man’s hour

the gratuitous grace of greed, grief, or gain,

the measure pressed and overrunning; now the cries

were silent on Lupercal, the Pope secret on Lateran.

Brisen in Helayne’s chamber heard the howl

of Lancelot, and beyond it the longer howl of the air

that gave itself up in Merlin; she felt him come.

She rose, holding the child; the wolf and the other,

the wind of the magical wintry beast, broke

together on her ears; the child’s mouth opened;

his wail was a song and a sound in the third heaven.

Down the stair of Carbonek she came to the arch

and paused beneath; the wolf’s hair rose on his hackles.

He dragged his body nearer; he was hungry for his son.

The Emperor in Byzantium nodded to the exarchs;

it was night still when the army began to move,

embarking, disembarking, before dawn Asia

awoke to hear the songs, the shouts, the wheels

of the furnished lorries rolling on the roads to the east,

and the foremost outposts of mountaineers scanning

the mouths of the caves in snowy Elburz, where hid

the hungry Christian refugees, their land

wholly abandoned to beast and Manichæan:

the city on the march to renew the allegiance of Caucasia.

A white wolf drove down the wood’s path,

flying on the tender knowledge of the third heaven

out into moonlight and Brisen’s grey eyes.

She called: ‘Be blessed, brother’; the child sang:

‘blessed brother,’ and nestled to its first sleep.

Merlin broke from the wood and crouched to the leap;

the father of Galahad smelt his coming; he turned,

swerving from his hunger to the new danger, and sprang.

The driving shoulder of Merlin struck him in mid-air

and full the force of the worlds flung; helpless

he was twisted and tossed in vacancy; nine yards off

the falling head of Lancelot struck the ground.

Senseless he lay; lined in the lupine shade,

dimly, half-man, half-beast, was Lancelot’s form.

Brisen ran; with wrappings of crimson wool

she bound the child to her crouching brother’s back;

kissed them both, and dismissed; small and asleep,

and warm on a wolf’s back, the High Prince rode into Logres.

Blanchefleur sat at Almesbury gate; the sleeping

sisters preserved a dreamless adoration.

Blanchefleur prayed for Percivale and Taliessin,

lords in her heart, brothers in the grand art,

exchanging tokens; for the king and queen; for Lancelot

nine months lost to Logres; for the house-slaves

along whose sinewy sides the wolf-cubs leapt,

played in their hands, laired in their eyes, romped

in the wrestle of arms and thighs, cubs of convection,

haggard but held in the leash, foster-children

of the City, foster-fellows of the Merciful Child.

Suddenly, as far off as Blanchefleur deep

in exchange with the world, love’s means to love,

she saw on the clear horizon an atom, moving,

waxing, white in white, speed in snow,

a silver shaped in the moonlight changing to crimson,

a line of launched glory.

The child of Nimue

came, carrying the child of grace in the flesh,

truth and taunt inward and outward; fast

Merlin ran through Logres in the wolf-month

before spring and the leaf-buds in the hazel-twigs.

Percivale’s sister rose to her feet; her key

turned, and Almesbury gate opened; she called:

‘Sister,’ but the white wolf lay before her; alone

she loosened the crimson wrappings from the sleeping Galahad;

high to her breast she held the child; the wolf

fled, moving white upon motionless white,

the marks of his paws dark on the loosening snow,

and straight as the cross-stamped hazel in the king’s house.

The bright intellects of passion gathered at the gate

to see the veiled blood in the child’s tender cheeks;

glowing as the speed in the face of the young Magian

when at dawn, laughing, he came to London-in-Logres;

or the fire built in Carbonek’s guest-chamber

where Lancelot lay tended, housed and a man,

to be by Easter healed and horsed for Logres;

where at Easter the king’s whole household

in the slanting Latin of the launched legions sang

Gaudium multum annunciamus;

nunc in saecula servi amaus;

civitas dulcis aedificatur;

quia qui amat Amor amateur.

(My translation)

The joy the multitude make;

Now forever in slavery to love;

Sweet city building;

For those loving amateur Love.

You have discovered some thought-provoking Apocalyptic comparisons – Abraham as father as far as he can tell properly if incomprehensibly willing to kill his only son (though I need to read all the details of The Apocalypse of Abraham), the dragon of St. John’s Apocalypse who “stood before the woman who was ready to be delivered; that, when she should be delivered, he might devour her son”, Nebuchadnezzar who should be a father to his nation being ‘schooled’ by being sent to eat grass like an ox! I don’t know it ever struck me before how Lancelot is getting something like the benefit of the ‘Nebuchadnezzar treatment’, while Arthur is in his dream thinking much like Nebuchadnezzar before his correction – “Is not this the great Babylon, which I have built to be the seat of the kingdom, by the strength of my power, and in the glory of my excellence?” (Daniel 4:27, Douay-Rheims). Maybe that benefit comes to Arthur, too, among his “whole household”, singing at Easter – as the Grail will be achieved by the Son of Lancelot on God’s terms rather than those of Arthur’s dreaming.

Sørina Higgins has happily paid a lot of attention to anachronism in Williams’s verse retelling. I keep thinking I should be trying to pay more attention to the thread of liturgy, and of anachronism in Williams’s use of liturgy. “What an image of the Pope”, indeed! I suppose this is the “Confiteor” at the beginning of the Mass: “I confess […] that I have sinned exceedingly in thought, word, and deed: through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault” beseeching all the saints, human and angelic, “and you brethren to pray to the Lord our God for me.” The poem then seems to move on through the Mass: Merlin knew “the Pope’s voice singing the Glory on Lateran” – but then no more liturgical details are given as the evening goes on – should we be able to guess some paralleling later story details that are given? But, the Confiteor apparently was not a part of the Mass in the form I quote till later than the time of Arthur and Taliessin and even the rise of Islam:

https://archive.org/details/liturgyofmass00pars/page/66/mode/2up/search/Confiteor

And this is at the time of the liturgical year of “the thin night air of Quinquagesima” – when the ‘Gloria in excelsis’ is not sung as part of the Mass. What’s going on here? Are we to think of that, and find another sense in “singing the Glory”?

In any case, it is fine to see Lancelot’s laying “tended, housed and a man” through Lent “to be by Easter healed”.

That Latin hymn is a fascinating thing, too – it seems to be Williams’s (at least, I’ve missed it, if anyone has identified it as a real (old) hymn, reused – like the one in The Chapel of the Thorn). I’m afraid (as can sadly be said of other parts of my edition!) a couple typos have crept in, above. The second line should end “amamus” and the fourth “amatur”.

Regarding Lupercalia, I have a post about it here: https://dowsingfordivinity.com/2014/02/14/lupercalia/

Thanks for sharing, Yvonne. That’s far more than I could have known!

You’re welcome— thanks for reading

Pingback: 2020: A Year of Reading: The Nerd Bit, with Charts | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “The Country Around Edgestow”: A Map from C.S. Lewis’ That Hideous Strength by Tim Kirk from Mythlore | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: The Romantic Theology Doctorate (DTM) at Northwind Seminary | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: The Romantic Theology Doctorate (DTM) at Northwind Seminary | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Lewis and Tolkien among American Evangelicals: Guest Post by G. Connor Salter (Lewis Scholarship Series) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: An Old Pictorial Map of Central Oxford (Are There Links to C.S. Lewis’ Fiction?) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “The Personal Heresy” and C.S. Lewis’ Autoethnographic Instinct: An Invitation to Intimacy in Literature and Theology (Congress2021 Paper) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: 5 Ways to Find Open Source Academic Research on C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and the Inklings | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Tolkien Studies Projects Sweeps the Mythopoeic Scholarship Award Shortlist in Inklings Studies (Trying Not To Say “I Told You So”) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Marsha Daigle-Williamson’s Reflecting the Eternal and Dante in the Work of C.S. Lewis, with Thoughts about Intertextuality (Good C.S. Lewis Studies Books That Did Not Win the Mythopoeic Award Series Insert) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Great and Little Men: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Letter about C.S. Lewis and T.S. Eliot | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “The Nightmare Alley of That Hideous Strength: A Look at C.S. Lewis and William Gresham” by By G. Connor Salter (Nightmare Alley Series) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Trees, Leaves, Vines, Circles: Reading and Writing The Layered Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Fiction: A Note on “Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth” and “Leaf by Niggle” #TolkienReadingDay | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Trees, Leaves, Vines, Circles: Reading and Writing The Layered Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Fiction: A Note on “Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth” and “Leaf by Niggle” | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Wherever I Go, That’s Where the Party’s At: Prince Corin as C.S. Lewis’ Harbinger of Joy, Guest Essay by Daniel Whyte IV | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “The Saxon King of Yours, Who Sits at Windsor, Now. Is There No Help in Him?” Thoughts on the British Monarchy from “That Hideous Strength” by C.S Lewis on the Death of Queen Elizabeth II (by Stephen Winter) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: The Literary Life in Dorothy L. Sayers’ Murder Mystery, Whose Body? (1923) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Veery nice post

Pingback: Inklings and Shapeshifters: Charles Williams’ Theology and Paul Schrader’s Cat People – Fellowship & Fairydust

Pingback: Alan Moore’s Birthday and From Hell – G. Connor Salter