I am pleased to announce that I have a new chapter out in a book on Teaching and Learning: “A Curious Synchronicity: Religious Studies as Inquiry-Based Learning in Higher Education,” pp. 232-249 in Applying Inquiry-Based Learning in Higher Education Across Disciplines, edited by Beth Archer-Kuhn, Stacey L. MacKinnon, and Natalie Beltrano in Cambridge Scholars Press, 2025. It is an academic book, so a little pricey. Thus, I would appreciate it if you could ask your local research university to purchase or otherwise make this text available for their libraries. Also, please share this note with anyone you think might be interested (like Religious Studies scholars, theologians, and curious teachers who love students). As regular readers know, I love teaching, and I have been enjoying researching the hows, whys, and wherefores of the craft (what we call pedagogy).

I’ll provide a little background about my own piece and an excerpt, including the Table of Contents. First, though, I wanted to talk about what we mean by Inquiry-Based Learning in Higher Education (IBL-HE).

Inquiry-Based Learning in Higher Education (IBL-HE)

Since 2015, I have been a core member of the University of Prince Edward Island Inquiry Studies team, led by Stacey L. Mackinnon. In this course, we work to reorient students’ understanding of their role by inviting them to be the pilots of their university (and lifelong) education. We do this by curating a curiosity-driven, student-centred, teacher-supported environment of collaboration and openness. Rather than being the experts in a discipline, we provide students with the frameworks and tools they need to see themselves in this new light.

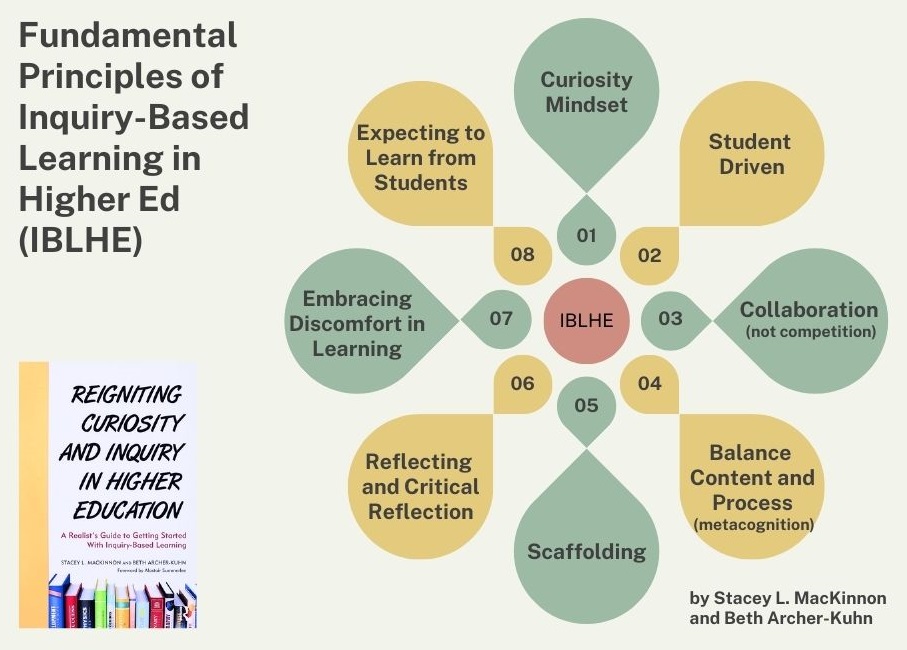

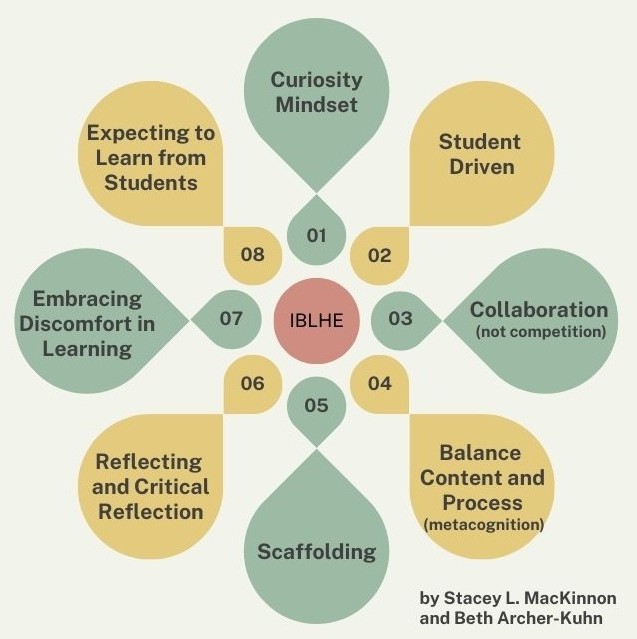

Stacey MacKinnon and her University of Calgary colleague, Beth Archer-Kuhn, are the leading scholars in IBL-HE. In Reigniting Curiosity and Inquiry in Higher Education: A Realist’s Guide to Getting Started with Inquiry-Based Learning (2022), Stacey and Beth introduce the 8-fold structure of fundamentals in IBL-HE: 1) Fostering a Curiosity Mindset; 2) Being Student Driven; 3) Focusing on Collaboration; 4) Balancing Content and Process; 5) Scaffolding Choices; 6) Reflecting and Self-Reflecting; 7) Managing New Learning; and 8) Expecting to Learn from Students. Current cohorts of Inquiry Studies are receiving this training as part of an IBL research project where students choose their research question, develop a research plan and methodology, and even choose how to share their discoveries. I have included a more detailed description of the 8 Fundamentals at the bottom of this note

Around this concept, a number of scholars throughout the world have been experimenting with IBL in the university and college curriculum. Beth and Stacey decided to follow up their groundbreaking framework with a series of essays on these IBL-HE experiences across (and sometimes within seemingly odd combinations of) the various academic disciplines. Natalie Beltrano joined Beth and Stacey on the editorial team, the foreword is written by Peter Felton and Josh Caulkins, and other contributors include Oluwakemi Adebayo, Nadia Delanoy, Ryan Drew, Sahar Esmaeili, Noor Fatima, Cari Gulbrandsen, Lavender Xin Huang, Mohammad Keyhani, Erika Kustra, Robin Mueller, Rosemary Polegato, Tomas Shivolo, Charlene VanLeeuwen, Justine Wheeler, and yours truly, of course.

Here is the book’s abstract, and you can find a PDF of the forematter at the bottom of this post:

Applying Inquiry-Based Learning Across Disciplines in Higher Education (2025)

This dynamic collection of voices re-imagining and fostering curiosity, collaboration, creativity and critical thinking expands across Canada to include work from Namibia. From AI integration and digital literacy in professional programs of business and social work to music, social sciences, science, social psychology, and religious studies, this book showcases the many unique ways that Inquiry-Based Learning (IBL) has transformed students into active investigators. Dive into chapters that explore communities of practice, student self and peer assessment, and navigation into real-world applications of IBL in public spaces, professional ethics and applications outside of academia. These real theories to practice stories, research-informed strategies, and transformative tools expand across disciplines. Perfect for new and experienced educators, facilitators, and academic leaders, this is your guide to student empowerment across higher education through self-directed learning that sticks. It’s not just about asking better questions, it’s about changing how we think, teach, and learn.

“A Curious Synchronicity: Religious Studies as Inquiry-Based Learning in Higher Education” by Brenton D.G. Dickieson

I had a lot of fun with this chapter. I wrote it in its very rough form in about a week during the summer of 2024–after a year or two of serious research and observation and while I was recovering from an illness. My chapter makes a good introduction to IBL-HE, but it also argues for the fundamentally interdisciplinary matrix of Religious Studies in public education (quoting myself):

Religion scholars—both at the whiteboard and the desk—can explore the great questions of the world using tools and approaches from anthropology, biology, cartography, dance, environmental sciences, fine arts, graphic design, history, Indigenous studies, journalism, kinesiology, linguistics, music, neuroscience, oriental studies, popular culture, quantum field theory, ritual studies, sociology, theatre, urban studies, Vedic textual criticism, writing, xenobiology, Yemeni political history, and Zoroastrian folklore. The core questions students can ask and the theoretical lenses they can apply are endless.

I spent a lot of time on that A-Z list! Here is an abstract of what I wrote in the chapter:

Public scholar, writer, and teacher Brenton Dickieson explores the transformative learning possibilities of an Inquiry-Based Learning in Higher Education (IBL-HE) model in the study of religion—from Atheism to Zen, from the Amish to Zoroastrianism. Classrooms become spaces where students investigate life’s big questions (“What is a human?”, “What do we mean by the Divine?”, “How do we know what we know?”) through their own cultural expressions and personal passions. Dickieson argues that teaching Religious Studies in a public university need not be about experts lecturing; it is collaborative storytelling where a documentary about Yakuza tattoo art, a Nigerian worship song, or curiosity about the weird and wonderful sparks discovery. Dickieson uses his “Japanese Religion and Culture” class at the University of Prince Edward Island to show that embracing discomfort in learning, recentring on student expertise, and providing intentional scaffolding—especially amid crises like strikes, storms, and plagues—makes learning deeper. Curiosity, not certainty—and wisdom rather than expertise—drives the inquiry journey when Religious Studies is taught in an IBL-HE.

I look forward to reading the other chapters in the volume, as I only read a couple of the other chapters in the editorial process. Let your local library know about this great new resource, but I can also provide more if you are interested (junkola[at]gmail[dot]com).

The 8 Fundamental Principles of IBL in HE

From MacKinnon & Archer-Kuhn, Reigniting Curiosity and Inquiry in Higher Education: A Realist’s Guide to Getting Started With Inquiry-Based Learning (2022)

FP 1: Fostering a Mindset of Curiosity – Modeling and encouraging a mindset of curiosity is key to making IBL-HE more than just a pedagogical tool, a classroom exercise, or a set of skills, but a way of thinking that can result in lifelong and life-wide learning for you and for students. As an instructor, let students see your enjoyment of exercising your curious mindset and inquiry skills so that a norm of valuing curiosity becomes the gold standard in your courses, in the classroom and outside of the classroom. Students need to hear and see curiosity from the instructor (and peers) and then practice or experience the validation of their curiosity themselves

FP 2: Being Student Driven – The best way to develop and strengthen students’ curiosity involves questions. Through the use of IBL-HE, students are encouraged, supported, and expected to pose their own inquiry questions, which they pursue throughout the course. They are supported by formative feedback from instructor and peers as the inquiry process unfolds. In an IBL-HE course students follow their own interests and pursue topics they want to learn more about.

FP 3: Focusing on Collaboration Not Competition – In an IBL course, the learning is not fully dependent, nor is it fully independent, but is interdependent (i.e., individual learning is enhanced and strengthened by the contribution of others, contributions the individual has the option to utilize or ignore as they see fit). When we emphasize collaboration (even on individual projects) and put the focus on the quality of learning rather than standing in the class, students are much more willing to offer their insights, consider the feedback of others as truly constructive, pose differing views, and engage in making the most of everyone’s learning, not just their own.

FP 4: Balancing Content and Process/Metacognition – Successful IBL-HE comes from a desire to not only have students learn facts but to think critically and creatively about the content and about the process of their own learning (i.e., metacognition). For the instructor, finding a balance between content understanding and metacognition is an important objective in an IBL-HE classroom. Students’ inquiry skills will allow them to determine what questions need to be asked and how to find the answers, consider multiple perspectives, and communicate their findings.

FP 5: Scaffolding, Choice, and Growth – There are many ways to include IBL in your practice (activity, course, program) and different levels of structure (structured, guided, open) you can choose from. It is fine to start just outside your comfort zone and grow your practice of IBL from there. Starting slowly is recommended. Some things will go smoothly, and others may not. Remaining reflective and using your own inquiry skills will help you to figure out how to support your students’ inquiry learning process. When you make your choices about the type of IBL-HE that you want to implement (structured, guided, open), you will also need to be mindful of the level of student support that is necessary within each IBL type. Remember, the instructor’s role in IBL-HE is a facilitator of student learning. The level of support is highest with structured IBL-HE and decreases progressively as you choose guided or open IBL. Introducing structured IBL-HE then means you are providing a significant amount of student support within a student-led inquiry learning process. This principle requires ongoing check-ins with students about their learning process.

FP 6: Reflection and Critical Reflection – Reflection is key for success, both for yourself and your students. Make note of what works and do it again. Reflect on why things did not go according to expectations, make some changes, and try again. Learn from your students’ reflections on their experience and consult them on ideas you are considering. Be explicit in asking which activities facilitated their learning and which did not, and why. Let them know that you adjust the course based on their feedback. IBL-HE requires more than simply reflecting on experience and behavior though. It necessitates students and instructors critically reflecting on all aspects of the inquiry journey from the creation of an inquiry question through to the effectiveness of different strategies for disseminating their findings to various audiences. Engaging in critical reflection helps us and our students refine our inquiry questions, identify and confront biases, consider causality, contrast theory with practice and identify systemic issues, key issues in creating a mindset of critical evaluation and enhancing the likelihood and quality of knowledge transfer.

FP 7: Embracing the Discomfort of New Learning – Implementing IBL-HE will likely raise the anxiety of some, if not all students initially (not to mention your own). They are being asked to trust a process that they very likely have not been exposed to in their educational career. As we know, new experiences can create anxiety. Although the level of student anxiety will vary, a handful of students experiencing a high level of anxiety, or even one or two, can heighten your own anxiety. How the instructor manages their own and their student’s anxiety will determine how the students’ progress. Transparency and modeling are important traits for the instructor. In terms of transparency, let students know what to expect, that this way of learning is new and different and will likely cause some initial anxiety. Modeling confidence in the process and trust in your student’s abilities will help to ease their and your own anxiety. After the first assessment and/or reflection tasks, students’ anxiety often decreases significantly. Think outside the box when considering how to help students embrace the discomfort of new learning by encouraging them to find support from varied sources: peers, instructors, research literature, and, when possible, community resources.

FP 8: Expecting To Learn From Your Students – Take every opportunity to learn from your students and make your classroom your own IBL project. Use what you are learning to customize the IBL-HE experience for each cohort, to plan for future cohorts, to test out new ideas, and to track your successes as well as your challenges. Remember that if you are doing inquiry well, finding answers will spur the next round of questions. IBL-HE is meant to be dynamic, so each experience brings you new insights, opportunities to try something different, and new questions to explore with your students. Whenever possible collect data on your students’ IBL-HE experiences and consider writing a SoTL paper or presentation to share what you’ve learned with others! Situating IBL in a postsecondary context provides an opportunity to examine its possibilities and implications for applied and nonapplied disciplines.