I have some exciting news! On Tuesday, I will be giving a talk in the “Theology on Tap” series. After a pandemic hiatus, it is lovely to see this event emerge again. A few years ago, I did my “Hobbits Theology” talk, officially called “Concerning Hobbits and How They Save the World.” I’ve linked that talk below, which I rewrote for a Northwind Seminary lecture a couple of years ago. It also has a place in my upcoming book.

This year, I pitched a new subject. I wanted to challenge myself and test out some ideas that have come out of my reading of two great 20th-century speculative fiction writers: Octavia E. Butler and C.S. Lewis. I also wanted to tackle a complex question–a wicked question, nearly an impossible question, a question I have been afraid to talk about but one that I think is essential to my calling as a father, teacher, neighbour, and theologian.

There seems to be a little buzz around the event. It is my first time being featured in UPEI’s “Campus Connector” digital magazine. I have since been rethinking my Star Wars shirt selfie in front of SDU Main building on campus as my official professorial profile pic. I suspect I’ll be getting an offer from the campus photographer at some point to get new headshots. 🙂

I spend a little time going into my thinking below, but here’s the blurb for those who want the quick version. It is not a livestreamed event, but hopefully they tape it like last time, so I can share it with you all.

“Because My Old Heart Would Burst”: A Settler’s Reflections on Indigenous Spaces in Octavia Butler and C.S. Lewis

While Octavia E. Butler and C.S. Lewis are quite different in style and worldview, their fantasy and science fiction novels excel at showing the complex relationship between indigenous folk and the powerful people who settle in their spaces. With Butler’s and Lewis’ stories in mind, Dr. Dickieson offers a theological reflection on his own experience of “home” in Epektwik.

Readers will know that I am a huge fan of Octavia E. Butler’s science fiction. I love her writing, but Butler is not easy to read. Her stories poignantly capture the complexity of forced interrelationships between settlers and indigenous peoples during situations of rapid technological and societal change.

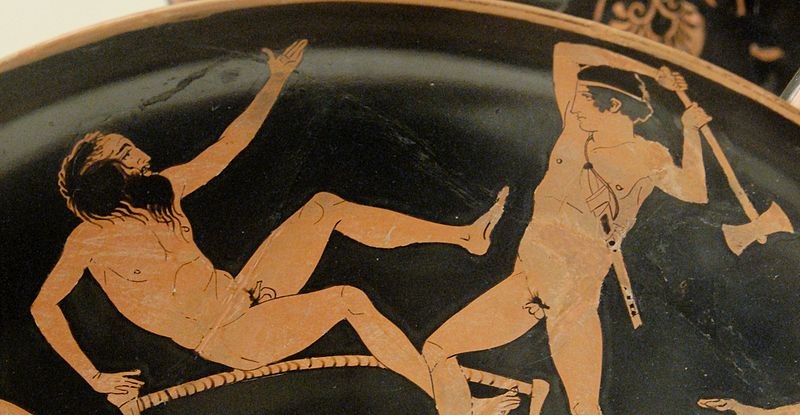

In a short story named “Amnesty,” an alien hive-mind species settles in Earth’s deserts and disrupts the global economy. It took the aliens years to understand that humans were sentient-sapient beings (what C.S. Lewis describes as “hnau“), and the discovery process included some atrocious acts. When frustrated and terrified humans ask why the aliens can’t go back where they come from, the protagonist human character, Noah, responds: “They’re here to stay … There’s no ‘away’ for them” (Bloodchild 167). They have nowhere to travel and no way to get there if they did. They put all their hopes in this new world. Earth is their home.

Similarly, in the Xenogenesis trilogy (or Lilith’s Brood), a species of alien genetic race-makers observes Earth in a mounting global nuclear holocaust. The aliens could tell that humans were hnau, but they did not understand until very late that the nuclear war was not consensual for most humans. The aliens rescue and archive a few hundred humans in suspended animation with the goal of a postnuclear reseeding of Earth. This is not mere altruism, though. These aliens are genetic treasure hunters, using the knowledge of the universe to evolve their own species. While humans are reliant on the aliens for a new chance to recover our species, the aliens become reliant upon the human-alien genetic bond.

These aliens, too, are homeless wanderers in space. When the protagonist Lilith describes her dependence upon the scientific masters who have saved them, her words are stark:

There is “nowhere to go, nowhere to hide, nowhere to be free” (Dawn III.3, “Nursery”).

While the stories are each unique in Butler’s work, they often feature what one of my MA students, Jens Hieber, calls “negotiated symbiosis.” A “symbiotic” relationship is one where species share a biological need for one another, like humans and microbiotics (so the yogurt commercials tell me). Or like those Egyptian Plovers and the crocodiles, or Clown Fish and Sea Anenom… Amenonm… well, watch Finding Nemo for that one.

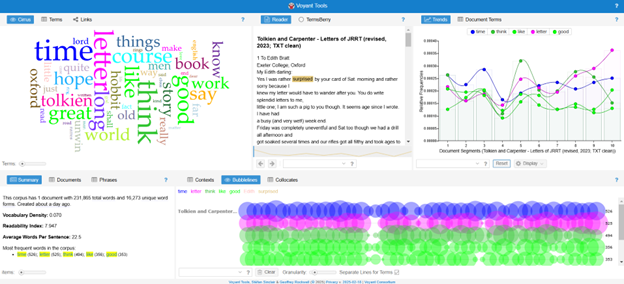

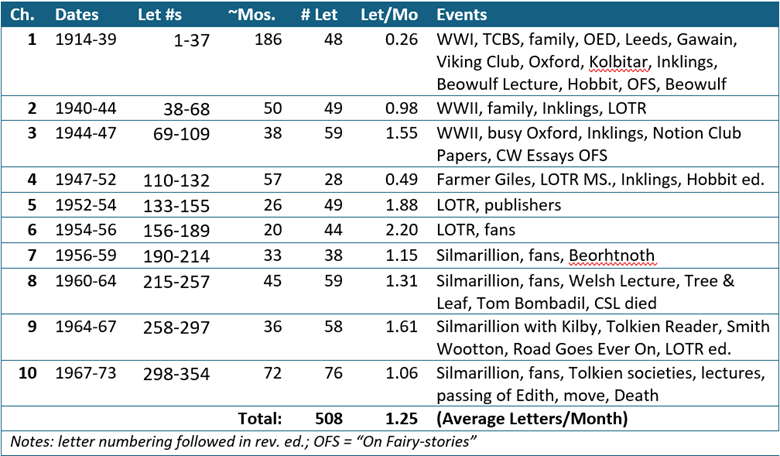

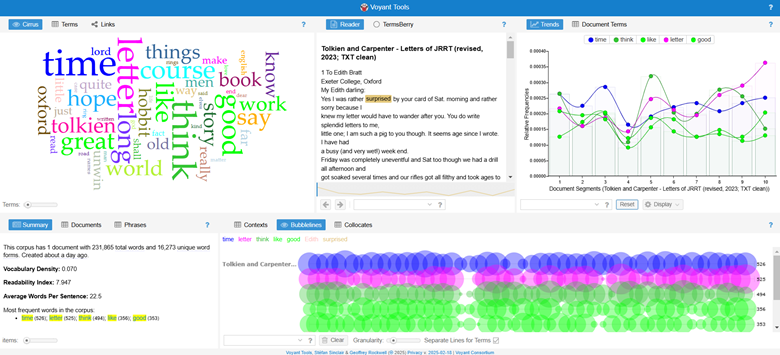

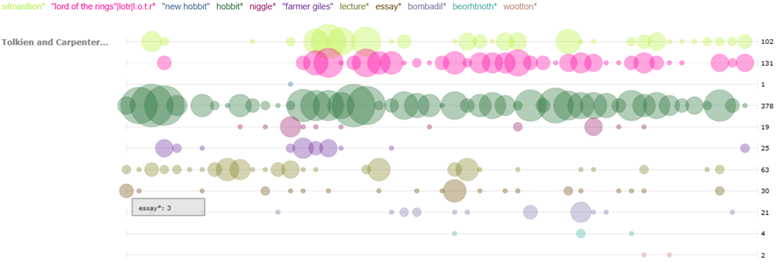

In Butler, that symbiosis might be parasitic or mutually beneficial. The negotiated symbiosis might be shared genetic makeup, like a species, or shared bodies and minds. In fact, the symbiotic relationships are so complex and diverse that for a Mythmoot conference in 2023, I made a spreadsheet:

Granted, not everyone is as enamoured by spreadsheets as I am. But it all helps me press in on the implications of Butler’s interspecies symbiosis when thinking about my own space.

I am Brenton Dana Gordon Dickieson, son of Dana, son of Roy, son of Percy, son of Charles, son of James Dickieson, who married Catherine Stevenson, with whom he migrated to Mi’kmaq territory. 205 years ago, my Scottish family began farming in beautiful Prince Edward Island—in Epekwitk, the “cradle on the waves.” We were part of a great migration, and we fought for the land that we cared for and lived with. I still own a tiny corner of that land.

This great migration, though, displaced the peoples that lived here. Canada’s First Nations had nowhere to go, nowhere to be free. Likewise, I have nowhere to go back to. I have no place in Scotland or Europe that is mine. For me, to go somewhere is to displace someone. PEI is my home. I am bound to this homeland of the dispossessed.

Butler helps me frame the problem and offers a thoughtful–and troubling–speculative framework for reconsidering Indigenous displacement, hybrid identity, and shared spaces. Some of her greatest work is about the trans-Atlantic colonial project of using Indigenous Africans to help displace the people who first called these lands home.

While Butler excels at visualizing the troubling realities of negotiated symbiosis, I encountered a more personal and vibrant response while reading C.S. Lewis.

Like Butler, Lewis is intensely interested in tyranny–whether that is colonial oppression, economic enslavement, state control, or hegemonies of the mind and heart. Whether that is Jadis’ century-long winter in Narnia, Dymer‘s Republic of perfection, or various eugenic, technocratic, and ideological superpowers in the Ransom Cycle, Lewis’ stories are often about control:

“Man’s power over Nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with Nature as its instrument” (The Abolition of Man).

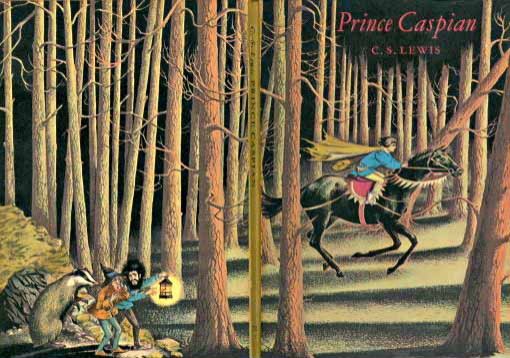

The stories have become increasingly personal to me. I was reading Prince Caspian when I suddenly caught a new vision of what was possible for me in my land of beauty, invention, and broken hearts–me with nowhere to go back to.

So this is what I would like to talk about in my Theology on Tap.