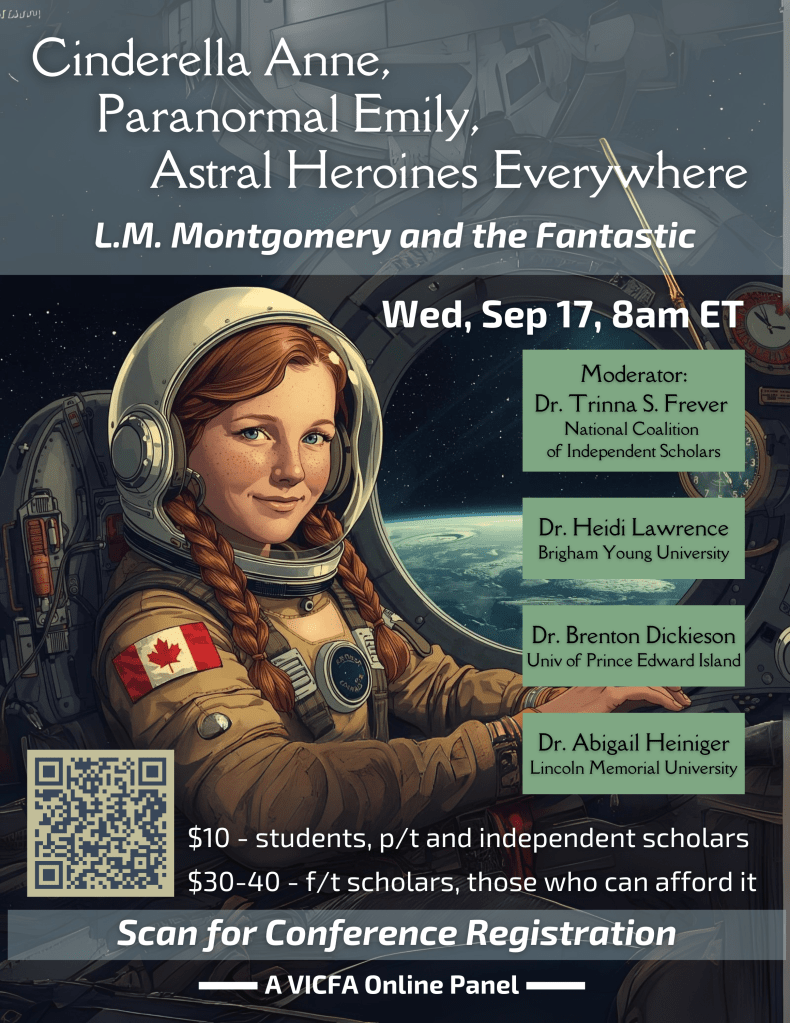

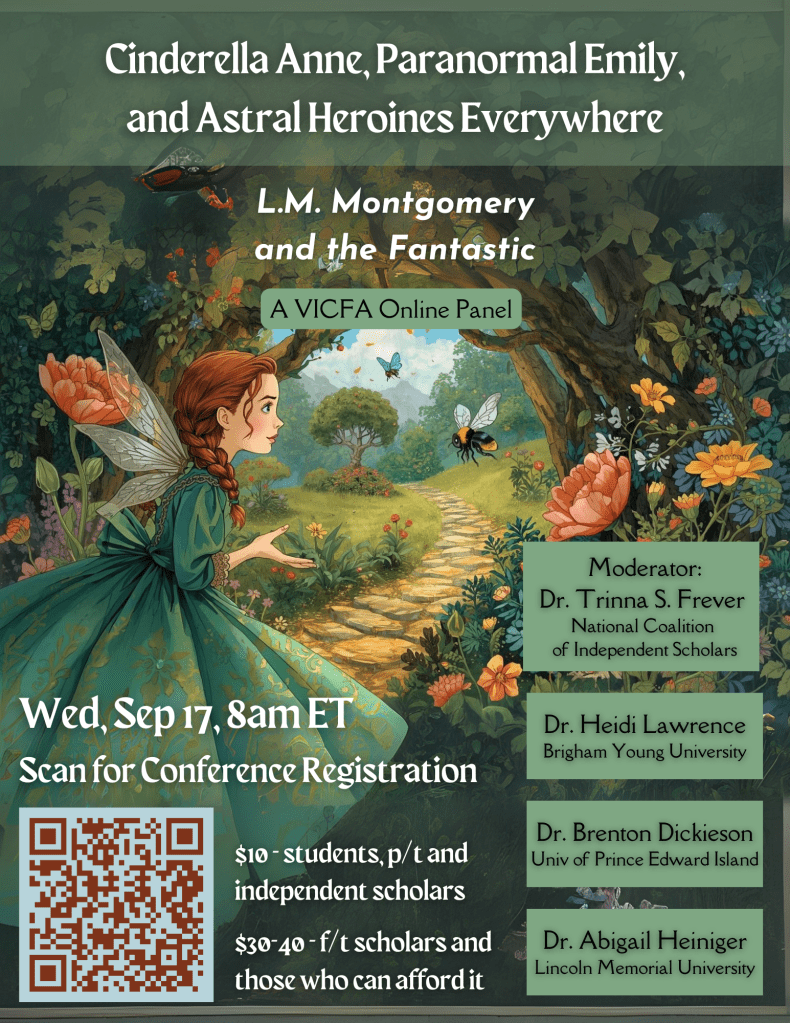

Right now, I am prepping for a conference panel tomorrow that I announced last week: “Cinderella Anne, Paranormal Emily, and Astral Heroines Everywhere: L.M. Montgomery and the Fantastic.” I’m working with with three fantastic scholars (see what I did there?): Heidi Lawrence and Trinna Frever (past MaudCast guests–watch for Heidi in season 3), and Abigail Heiniger (whom I’m meeting for the first time). You can see more about that below, including how to register for the VICFA online conference.

Meanwhile, I want to use a bit of pushback I received to talk about what I’m doing in my larger project of reading Prince Edward Island‘s beloved Lucy Maud Montgomery. While most of the feedback is positive and curious, I have received two kinds of resistance from this panel announcement and in previous online classes in Signum University’s SPACE program.

First, since Montgomery is presented to us as a solidly realistic imaginative writer, there is a focused concern about genre. Second, there is a more intuitive concern about whether these kinds of enterprises honour Montgomery’s gift to us.

I confess that playing with the iconography of Anne of Green Gables has some risks–whether in a lightly steampunk space capsule or on the edge of fairyland (or so I meant to evoke). I don’t know how to respond to this kind of argument, exactly, but I hope, in answering the first challenge, I can show the degree to which I seek to honour Montgomery’s life work.

First things first: am I bending genre definitions too far to think about the fantastic when I’m reading Montgomery?

I’ll start with a question: Where do you find Montgomery at your local independent bookstore? Here in PEI, she gets her own section, but I doubt that is the case in many places beyond our magical island. Often enough, I find some of her novels in Children’s Books, or there may be a ragtag collection of her works in Canadian Literature. Increasingly, though, I find Montgomery in the “Classics” section–and not without reason. Anne of Green Gables is undoubtedly a classic.

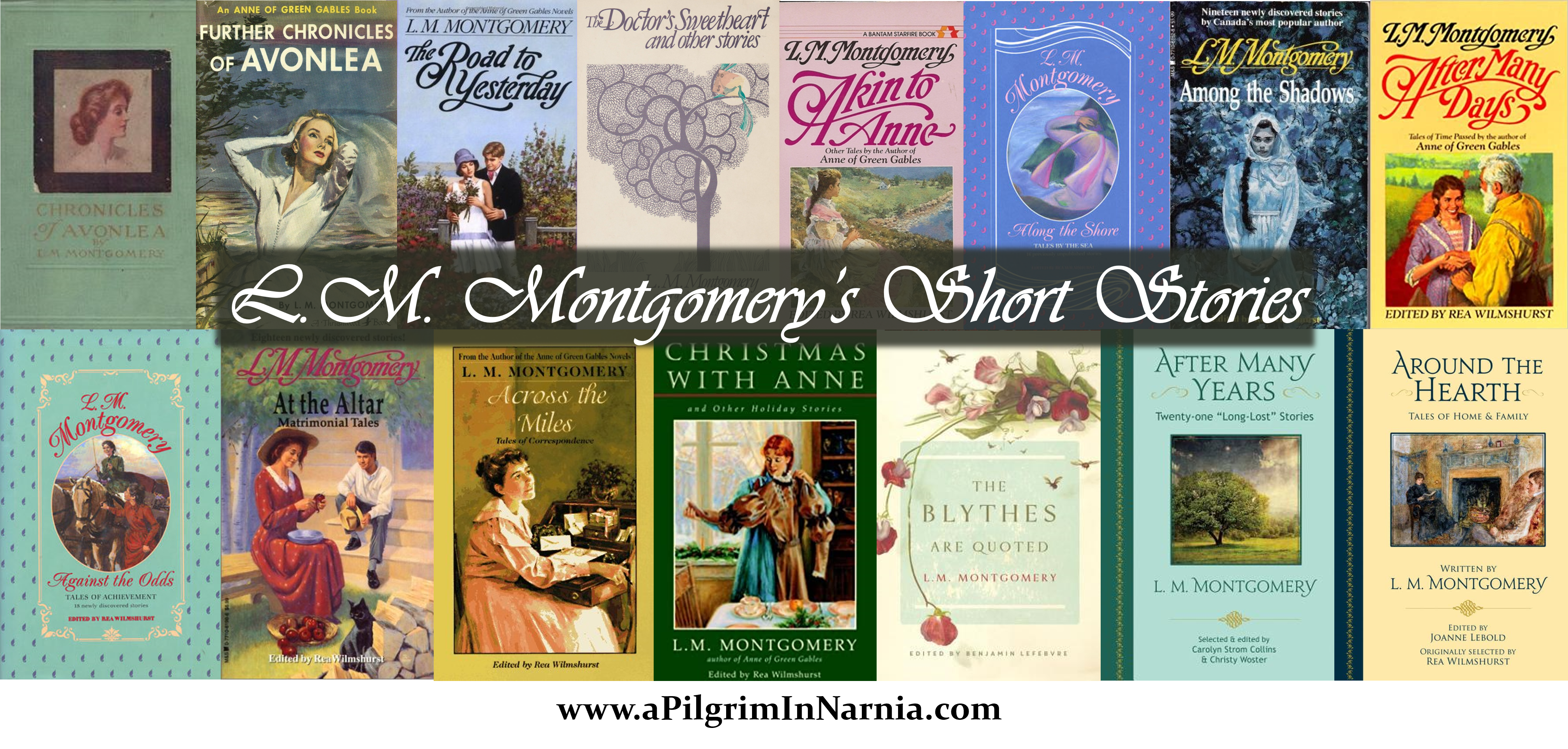

When it comes to classification by age group, region, or status (what else is a Classics section?), it gets a little awkward. She is a children’s writer, but what about The Blue Castle, a decidedly adult book with adult themes? Most of the long-form fiction is set in PEI, but Montgomery published writings from and about Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia, and Ontario–including Jane of Lantern Hill, a brilliant but late and less-recognized work that begins and ends in Toronto. Jane is a classic to me, but not to the general public. What about The Watchman, and Other Poems, one of the few collections of her relatively unknown poetry? Or what about Montgomery’s journals–nearly 50 years of life writing in print and available? Or her 500+ published short stories?

As a follower of Ursula K. Le Guin, I am perhaps too quick to be dismissive of genre. After all, Montgomery was a very intelligent businesswoman and selected her markets carefully. Still, Montgomery, like Le Guin, had her work narrowed and dismissed because of genre categories. In both cases, some of that dismissiveness was gender-based, with Le Guin being panned as “soft SciFi” and Montgomery as “just a girl’s writer.” The times moved on during Le Guin’s career, but a generation of Montgomery scholarship was lost to the literary gatekeeping of the label makers in the industry and academy.

Plus, you may have noticed, I’m not Montgomery’s primary reader. Should I only shop in women’s fiction now because I like Emily of New Moon?

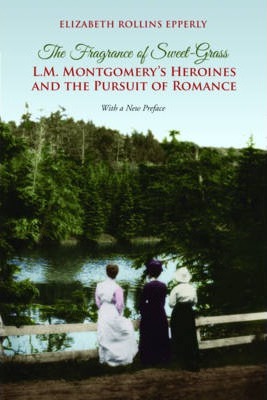

Elizabeth R. Epperly has written one of my favourite works of literary criticism, The Fragrance of Sweet-grass. Part of what Epperly is doing is reading Montgomery as a romantic writer. It is a slippery definition, “romantic,” but in Montgomery’s time, it had a broad set of categories.

Much later, in the early 1930s, C.S. Lewis provides seven potential definitions without coming to stories of falling in love (see the Preface to the 3rd edition of Pilgrim’s Regress). When Lewis began writing science fiction and fantasy on the eve of WWII, he was writing “interplanetary romances.” There is some kinship in the worlds of romance–and behind all of them are George MacDonald, the Arthuriad, and the fairy tale traditions.

Beyond this, though, scholars and artists have been colouring outside the lines that are drawn around Montgomery’s writings, which limit as much as they help. Here is Epperly’s proposal:

“perhaps we can separate Montgomery’s confinements by genre and expectations from her liberations of imagination and perception to see how romance is, ultimately, the power we give to the visions we endorse” (Elizabeth R. Epperly, The Fragrance of Sweet-grass, 250).

When we push against genre boundaries and read the text, there are some intriguing aspects of Montgomery’s storytelling that go beyond strict realism. Besides miracles in various stories and an abiding sense of Providence in certain of the novels–is God fantastic or realistic in our world today?–there are little elements of the fantastic. Some of my favourite tales have hints of enchantment, bewitchery, faërie, dreams and visions, ghosts and the supernatural, the prophetic, other ways of seeing and knowing (like second sight), and moments of the deeply improbable, if not impossible.

The fantastic plays along the edges of the imaginative worlds Montgomery builds–and sometimes much closer to the centre.

Moreover, within the frame of the story itself, the characters (and sometimes the audience) have emotional experiences bound up with the uncertainty about what is true–or even something like hope or stubborn belief in the fantastic. We know as readers that Anne and Diana have peopled their woods with imaginary ghosts, but the uncanny elements cannot be so easily dismissed in the Emily stories. In the Story Girl’s world, we do not know if wanderers and wise women can really be witches. If we simply dismiss the possibility as readers, we narrow the scope of Montgomery’s imaginative vision.

I agree that Montgomery is not a writer of genre fantasy as we see it developed in the 20th century in the vein of Tolkien, Lewis, or Le Guin. I’m not trying to make a claim about the books themselves–at least not initially.

Rather, by considering fantastic elements in Montgomery’s realistic fiction–by sort of switching the bookshelf tags around a little bit–I’m adapting a certain line of sight into the books. I am the kind of lit scholar and critic who does not just have a single way of reading a story or poem. Instead, I use all the tools in my reading toolkit to live within the world of the story as see what I can see. Sometimes I ask about boys and girls and gender or reflect on power or write as a theologian of culture. In this particular reading, I am doing things like this:

- I study the fictional worlds (speculative universes) that Montgomery built to find what meaning is contained in the fabric of the worlds themselves.

- I play with Fantasy Mapping, particularly with effects of time and space in Avonlea.

- I glance into Montgomery’s pictures of Faërie to see what it means artistically, relationally, and spiritually.

- I wonder about Farah Mendlesohn’s 4 types of fantasy–portal/quest, immersive, intrusive, and liminal–and use her framework to ask questions about certain writing choices Montgomery made.

- I think about what it means that my geographical space in Prince Edward Island is largely defined by a world that is not–as the skeptics say–“real.”

- I ask readers the simple question, “What makes Anne magical?” It’s a wonder what people tell me.

Would Montgomery have put Anne is space? I doubt that kind of fiction would have interested her–though she was curious about modern inventions and spent a part of her time considering the heavens. But, coincidentally, I am reading Samantha Harvey’s Orbital, and I can’t help wondering if a dreamy eleven-year-old Anne in 1969 would have looked up to the sky when she heard about the moon landing on the radio.

I am simply conducting a personal reading experiment. Experiments may fail, after all. Not every glimpse of phantasmes and fairies in her stories is otherworldly. Still, when I follow the Horns of Elfland in Montgomery’s work, I tend to see something new.

And even then–even if the experiment fails–the results can be worth the time. For me, rereading Montgomery is always worth the risk. And that is the best way I know that I can honour Montgomery’s literary gift to the world: to read and reread what she wrote.

Cinderella Anne, Paranormal Emily, and Astral Heroines Everywhere: L.M. Montgomery and the Fantastic (Conference Panel Abstract)

This panel seeks to remedy a significant omission in fantasy fiction studies and L.M. Montgomery studies by exploring Montgomery’s works in a fantastical context. Anticipated topics include Montgomery’s invocation and adaptation of fairy tales, use of the paranormal and otherworldly, depictions of magic and the magical world, and astronomical/cosmological themes in her work.

Session will include short, informal presentations from each scholar discussing their work in this field, moderator questions and panel discussion designed to illuminate the topic(s), and at least thirty minutes of audience Q & A to conclude the session. We hope you can attend!

Register here: https://iaftfita.wildapricot.org/event-6255095

All of this is part of the Virtual Conference of the Fantastic in the Arts (VICFA). To attend the panel, you need to register for the conference, but the entry bar is low: $10 for students/unfunded scholars and $30-$40 for funded scholars and those who can afford it.

Questions of genre are of minor interest. The important question is how to maintain an airtight seal when braids are dangling out of one’s helmet.

LikeLike

I know, right?! I laughed at this space ship I made and the likelihood that Anne would be a frozen corpse now. Not engineering realism. Also, I couldn’t get anything geographically specific or even believable through the window. I just ain’t got the skills.

LikeLike

Thanks, Brenton, for these suggestions about discussing the non-realistic elements in L.M. Montgomery’s books. I am not an expert on Montgomery. But in an article I wrote years ago about “epiphany” in children’s books, I mentioned the “flash” that is a crucial mystical experience in the “Emily of New Moon” trilogy. What is that “flash”? How and when does it happen? How does it change Emily? Does it connect Emily with another world, or a separate “dimension” of what is otherwise a realistic word of donuts in the cookie jar and a lost ring, and sunsets?

Let me encourage you, cautiously (because I tend, at least so far, to regard Montgomery as mainly realist, with any fantasy / mysticism / religion /spiritualism as as a small element in the whole story — at least the Montgomery stories I know — a world that feels closer to Laura Ingalls Wilder than to “Narnia” or George Macdonald), with a different example that I have been researching for decades.

Elizabeth Goudge.

There is no doubt that a book like “The Little White Horse” (the central image is a unicorn that we are expected to accept as real, however magical) is a fantasy. But so much of it reads and feels like a real historical novel (set in south-west England around 1834) that we swoop over the fantasy, when we find it, and focus on the real little girl, Maria Merryweather. (We even accept that the big dog, Wrolf, is just a big dog, when all the way through he is a lion. And the cat in the kitchen can communicate by drawing, with his tail, images like rebus-hieroglyphics …)

But many other novels by Goudge (her “Eliot / Damerosehay” family trilogy that begins with “The Bird in the Tree”; and “The Castle on the Hill”, a war-time novel set in the Luftwaffe Blitz of London and England; and “Gentian Hill”, an historical novel also set in south-west England around the time of Napoleon and Nelson; and “The Dean’s Watch”, an historical novel set in the east of England around 1870; and her first novel, set on one of the Channel Islands around 1875) are realistic.

That is, they look and feel realistic, through and through, until you discover that many of them include GHOSTS. Some have moments (epiphanies) of mystical insight that is almost like listening to an angel (and Goudge occasionally refers to seraphs, singing). Some have deep telepathy-like communication between hero and heroine. Some have dreams in which characters meet and interact, or experience something like astral travel. Some have deep connections between here-and-now characters and long-ago characters that borders on reincarnation.

In short, although Elizabeth Goudge is known (and was popular and famous in her lifetime) as a realist writer (and misunderstood as a writer of Romances for women, as a loose genre; often Historical Romances: she is far more of a psychological existentialist Christian mystic), she is a fantasist / spiritual writer.

You may find elements in Montgomery that show her as a fantasist / spiritual writer.

Telepathic emotional connection between heroine and hero?

Ghosts or a haunted sense of the past?

Dreams that reveal true things, and allow “travel” from a character’s person-here to somewhere-different.

A sense of people-now sharing aspects of people-past.

Glimpses of a numinous otherwhere / otherlife.

Good luck and happy reading!

LikeLike

I clicked “like” when you posted so that you knew I had seen and appreciate your response. Elizabeth Goudge truly is on my to-be-read list! I do like that she has this theological centre, as well.

LikeLike

Thanks for this – and the previous post – and to the commenters for their comments!

LikeLike

Something that sprang to mind in reading your remark above – “Would Montgomery have put Anne in space? I doubt that kind of fiction would have interested her–though she was curious about modern inventions and spent a part of her time considering the heavens” – was the dream-travelling in Tolkien’s Roverandom with “the dark side” of the moon “where sleeping children come down the moon-path to play in the valley of dreams” (as the editor’s Introduction puts it). That, in turn, made me think of the fascinating discussions of possibilities – and apparent instances – of ‘space travel’ in his Notion Club Papers. Would, for example, MacDonald’s use of ‘dream travel’ possibly have conduced to Montgomery trying some ‘dream-space-travel’ (even if it did not in fact)?

LikeLike

Hi David, it just occurred to me that you may not have seen that I kind of responded to what we were talking about here. I responded on the announcement post this way:

Would Montgomery have put Anne is space? I doubt that kind of fiction would have interested her. But personally, she liked electricity, the telephone, indoor plumbing, globalized journalism and post, the radio, and film. She took to photography and would have loved more access to astronomical tools. Sometimes she was an early adopter; sometimes she felt like Anne and Diana, who find it funny that little ole Avonlea has phones.

I don’t know what LMM would think, honestly? But I’m not trying to bend anything into moulds wherein they are ill-fitted. If the experiment fails, fair enough.

I do like your note about “dream travel,” and she quite loved Back of the North Wind.

LikeLike