Hello, fair folk, far and near! I wanted to let you know about one of the handful of talks and papers that have occupied a good deal of my research and reading in 2025. Next week’s Monster Fest in Halifax, NS is an international festival focused on the construction of monsters and monstrosity. St. Mary’s University is hosting us for a few days of monsterology. I’m looking forward to discussions of Frankenmetrics, Leviathan, Teratophilia, Djinn and Ghouls, Cat Ladies and Trad Wives, a vampire autoethnography, and the “Unholy Trinity of Vampires, Zombies, and Copyright Law. A colleague of mine, Ariana Patey, is speaking about “’Absurd, Race-Crazed Monster’: Monstrosity, Horror and Transformation in the Catholic Alt-Right.”

I’m not sure if I have the courage, energy, or interest in self-punishment to attend the Monster’s Ball. And I’m a little concerned about the 15-minute limit (I had planned for 20). Still, I am working on something that is in continuity with a theme I have been thinking about for some time, but have not found the time to articulate.

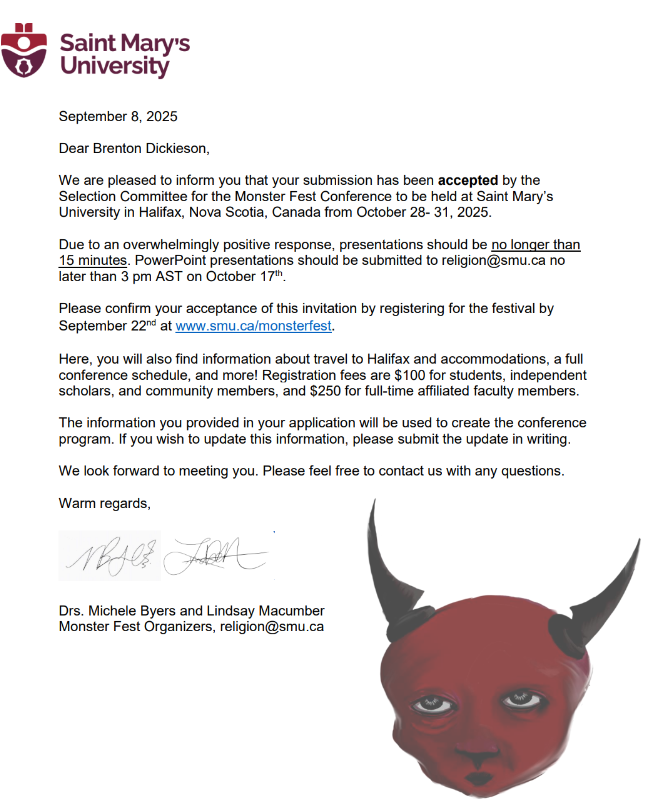

If you are local, check it out at https://www.smu.ca/monsterfest/. And here is my abstract, for anyone who may be interested, followed by my acceptance letter!

“The Monster in Me: C.S. Lewis’ Inversion of the Monstrous Other in his Speculative Fiction”

Brenton D.G. Dickieson, PhD

In his earliest unpublished, unknown, and disregarded fiction, C.S. Lewis’ protagonists encounter grotesque, chimerical, and abhuman otherness: the Mothlight of Yesterday, the unseen Bethrelladoom, the half-blind all-father, a misformed teratogenic bastard, dragons of fire and ice, giants of despair and madness, and—somewhat on the nose—Nazi-sympathizing dwarfs. Whether writing as an atheist philosopher or a Christian seeker, however, the true enemies the protagonists flee are God and their own hearts.

In Lewis’ first popular science fiction, Out of the Silent Planet (1938), the timid Cambridge philologist, Dr. Ransom, is kidnapped by an aristocratic scientific team in their attempt to colonize Malacandra (Mars) through the subjugation or eradication of the planet’s three evolutionarily distinct sentient-sapient species—human-like in intelligence but abominably uncanny in form. Fleeing from his English captors and the alien bogies of his imagination, Ransom encounters true “humanity” among indigenous Malacandrians. His idyllic life shatters when his comrades are murdered by classical European colonial invention—an English rifle—and Ransom must face the real monsters at last.

C.S. Lewis’ sometimes troubling relationship between monstrosity and alterity includes an element of prophetic self-critique that is critical to understanding the nature of temptation in The Screwtape Letters, the heart of each quest in Narnia, and the technocratic evil of his dystopic writings. This paper draws the line of continuity through his early fiction into his more mature corpus, demonstrating that “I” as the reader will always misunderstand the “other” in Lewis’ speculative universes unless I consider the monster in me.

Prof. Dickieson,

Congratulations (and hoping you pull through) on the Monster Fest event! A brief look through the rundown of the papers given at the event shows a lot of interesting topic and variety on display. The standouts to me are the papers on Dante’s use of the Monstrous in his construction of the “Inferno”. As for Prof. Patey’s paper, I’m forced to wish her not only good luck, but also hope that she’s able to stay safe while making her voice heard. It’s alarming to even have to say such a thing, and so, as Charles Williams might observe, here we are. The sense of irony is difficult to appreciate when it’s happened, and continues to happen to others, however. Still, it’s an act of courage that I genuinely hope she’s successful at. One thing I am grateful to see is a discussion of Baseball as a metaphor in the fiction of Stephen King. In particular I am curious to see how his novel “The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon” is treated in terms of concepts like the Sacred.

For instance, I have read at least one critic (Stephen J. Spignesi) wonder aloud if King might not have been Inspired by William Blake’s poem “Little Girl Lost” when it came to writing the story of a young Red Sox fan lost in the woods, and having a series of Supernatural encounters that harken back to the kind of borrowed Medievalism and Elizabethan tropes that marked the Romantic phantasmagoria of Blake’s poetry. A standout sequence in the King novel is when the young girl comes across a stream, with three hooded figures standing on the opposite side of it. Each one lifts its hood, and then offers the titular Girl a worldview to either accept or reject. One is Naturalist, the other Supernaturalist, while the third is best described (using King’s own critical terminology, see “Danse Macabre”) as a Dionysian Agent of chaotic Randomness. In other words, the diabolic. It’s the sort of sequence you would expect to find in the likes of Bunyon, Milton, Spenser, Blake, or even George MacDonald, for that matter. It’s easy to see how Spignesi might raise the question of a strand of Blakean Romanticism running through the text. It’s with this knowledge in mind that I hope Fred Mason one day decides to make his paper available for others to read!

Speaking of Stephen King, what’s interesting is that his own thoughts of the thematics of Horror might just bear a surprisingly useful rubric for what you are discussing in your own essay, Professor. You work is structured around the idea of the Monster Within, as opposed to a threat from without. What’s interesting about that is how in the aforementioned “Danse Macabre”, King devotes some page space to just this idea. He claims that “All tales of horror can be divided into two groups: those in which the horror results from an act of free and conscious will—a conscious decision to do evil—and those in which the horror is predestinate, coming from outside like a stroke of lightning. The most classic horror tale of this latter type is the Old Testament story of Job, who becomes the human Astro-Turf in a kind of spiritual Superbowl between God and Satan.

“The stories of horror which are psychological—those which explore the terrain of the human heart—almost always revolve around the free-will concept; “inside evil,” if you will, the sort we have no right laying off on God the Father. This is Victor Frankenstein creating a living being out of spare parts to satisfy his own hubris, and then compounding his sin by refusing to take the responsibility for what he has done. It is Dr. Henry Jekyll, who creates Mr. Hyde essentially out of Victorian hypocrisy—he wants to be able to carouse and party-down without anyone, even the lowliest Whitechapel drab, knowing that he is anything but saintly Dr. Jekyll whose feet are “ever treading the upward path (64-65)”.

King also makes claim that’s somewhat interesting from a critical perspective. He says that “Novels and stories of horror which deal with “outside evil” are often harder to take seriously; they are apt to be no more than boys’ adventure yams in disguise, and in the end the nasty invaders from outer space are repelled…And yet it is the concept of outside evil that is larger, more awesome…Bram Stoker’s Dracula seems a remarkable achievement to me because it humanizes the outside evil concept; we grasp it in a familiar way Lovecraft never allowed, and we can feel its texture. It is an adventure story, but it never degenerates to the level of Edgar Rice Burroughs or “Varney the Vampyre (65)”.

The basic gist of your argument therefore seems to fit well into the critical rubric that King has set up. The major difference being that perhaps Lewis has found a way to combine both approaches into more than a single narrative. It’s interesting food for thought. Which means, needless to say, that this sounds like an essay worth looking forward to. Also, congratulations for such a creative reading of THS. Somehow, it never occurred to me that the entire novel could fall under the category of the Dream Vision. A kind of genre mélange between H.G. Wells, George Orwell, Lewis Carroll, and Dante. If it’s at all possible to sustain this take, then while I’m not sure it makes “Strength” as successful as its two earlier siblings, it nonetheless could act as a display of Lewis’s skill as a secondary world builder.

LikeLike

Minor correction: Boys Adventure YARNS.

LikeLike

Wow, I have not read Danes Macabre in a few years, late 2010s, methinks. I have to look at the full context of that argument. I haven’t thought through the consequences of it, but I’m tempted to do so now.

LikeLike

Prof. Dickieson,

The context takes place as part of a discussion of how three now classic, Gothic Set Texts, have defined the parameters of the Horror genre ever since their publication. One is Dracula, the other is Frankenstein, the third of Jekyll and Hyde.

In nice CW style touch, King uses the metaphor of these works as three winning or Fortunate Cards in a Tarot Deck. He sees Stoker, Shelley, and Stevenson as, not responsible for the invention (Co-creation?) of Inside and Outside Evil. It just wound up that their literary efforts were the ones who gave this old, dichotomous moral Mappa Mundi tradition the best artistic expression for modern audiences. It can all be found in Chapter III, “Tales of the Tarot”.

LikeLike

Prof. Dickieson,

For what it’s worth, Scott McLaren has written an essay, “Saving the Monster: Images of Redemption in the Gothic Tales of George MacDonald”. He studies MacDonald’s use of the Monstrous as devices of both sin and Salvation, and I thought it offers a nice companion study to your own efforts. A PDF copy of McLaren’s critique can be found here:

https://www.worksofmacdonald.com/past-features

Hope this proves useful.

LikeLike

I thought of Tolkien’s essay, The Monsters and the Critics in which he contrasts Grendel and his mother with the critics who reduced the great Old English poem of Beowulf to an artifact of historical interest.

LikeLike

I was thinking about that, Stephen–a paper like “Tolkien and the Monstrous Critics” as a kind of precursor to monster studies. But I disciplined myself and stayed central to what I’ve been working on this year.

LikeLike

I love that, Brenton! Surely the Professor would have approved. But I am sure you were right to stay disciplined.

And slightly off piste as well. Have you been following the wonderful work that Malcolm Guite has been doing on the Arthurian myth? The first volume of his poetic retelling comes out in Spring of 2026. I have been listening to excerpts from it on his YouTube channel for a while now and feel that it is his master work. I listened to a lecture he gave recently in Nashville, Tenessee in which he spoke about the wonderful section in That Hideous Strength in which the community of St Anne reflect upon the way in which, from time to time, the myth of Logres and of Arthur are able to re-enchant Britain. I remember writing about this when I wrote a piece on your blog publicising The Inklings and King Arthur and am very excited that Malcolm sees this very much the same way. Malcolm feels that Logres can re-enchant the whole English speaking world and judging by the response from a large Tenessee audience they feel this quite viscerally too.

LikeLike

Pingback: “At war with all wild things”: A Settler’s Reflections on C.S.Lewis and Indigenous Spaces (Iași, Romania) | A Pilgrim in Narnia