It is chilly and pouring rain here in Prince Edward Island … normal weather for the week of Remembrance Day. Anne of Green Gables and I both love Island Octobers, but I struggle with the dying-dark and dreary days of November. I was hoping a change of atmosphere would bring an uplift this November. I have been planning to attend the C.S. Lewis conference at Alexandru Ioan Cuza University in Iași, Romania. Besides a different experience of light, I was hoping to meet good friends, colleagues, and students in this burgeoning intellectual centre of Eastern Europe.

Alas, I cannot make it Iași, and I am feeling a bit Eeyore-ish about missing out. There is an online registration for the hybrid conference–check it out here–and the folks there are kind enough to let me present digitally. Still, it isn’t the same thing … and I haven’t had the heart to look up the weather in Iași today.

Instead of moping, I spent part of the day working up the materials for the idea I am presenting. I am continuing with a theme that I have been focusing on all year, including my talk on Out of the Silent Planet at MonsterFest last month and my MythMoot discussion about “Being Hnau and Harry Potter” at Mythmoot in June. It goes back even further, actually, to an in-class lecture in 2022 and my Mythmoot paper in 2023 on ‘Nowhere to go, nowhere to hide, nowhere to be free’: A Settler’s Reflections on Indigenous Spaces and ‘Negotiated Symbiosis’ in Octavia Butler’s Literature.”

The unwieldy title of the Octavia Butler paper reveals how I’m struggling with a concept that is somewhat beyond myself. I keep talking about it from different angles and perspectives and finding new approaches, but not getting to the point of definitively saying the thing I need to say. Some people write to tell the world; some write to hear their own voices in a land of echoes. I write, at least initially, to discover what I know.

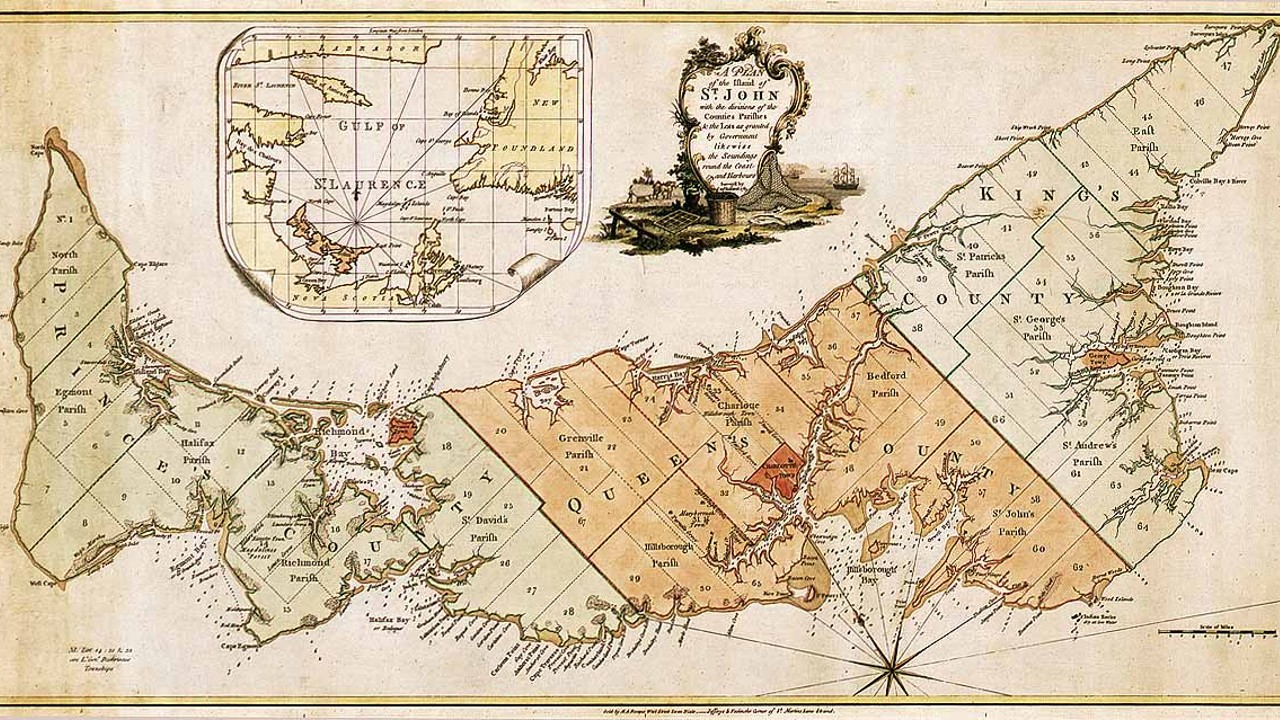

For my Romania talk, I am situating C.S. Lewis in a distinctly Indigenous studies space. In part, it is an echo of my Theology on Tap local talk back in the winter, which was not recorded, unfortunately. I gave that public lecture in this place I inhabit: Prince Edward Island, Epekwitk to the local Mi’kmaq folks, Abegweit in L.M. Montgomery‘s imagination, the Land of the Red Soil, the Cradle in the Waves, the Million Acre Garden of the Gulf. I am the descendant of settlers who, in their attempt to make life beautiful and make the world better, were part of a movement that caused great harm to the people who were already living here. In this way, I am a settler, but Epekwitk is my home. I am a native Prince Edward Islander, but not one of our Indigenous peoples. I belong nowhere else. It is deeply unsettling.

In Romania, I’m attempting to put all of this in a context that has a completely different kind of history from Canada and the United States, and then show some ways that C.S. Lewis speaks into this conversation–not as an expert, but with beauty, truth, and goodness. Romania has its own stories of conquest, displacement, and development, and I would love to learn more about them. However, in reading Narnia closely, I want to try to connect that audience to this Island space in which I endeavour to live well as it inhabits me.

If the talk is taped and I can share it, I will do so. Meanwhile, here is the title and a somewhat expanded description (though I already see that I am saying too much for a 15-minute talk!). I look forward to comments or seeing you online!

“At war with all wild things”: A Settler’s Reflections on C.S. Lewis and Indigenous Spaces

From the beginning of his fiction project in “Bleheris,” “Loki Bound,” and Dymer, to his mature and popular fantasy novels, C.S. Lewis is always writing about tyranny. When Lucy first finds her way into that magical world, the land is under the yoke of a century-long winter. We learn about this “always winter and never Christmas” reign through the stories and folklore of the Narnians as they live lives of resisting or giving in to the pretender’s cruel reign. Slaves are liberated in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, The Silver Chair, and The Horse and His Boy as Narnia negotiates its spaces between and among empires and colonies. In The Last Battle, these pressures finally collapse as colonial powers flood into Narnia through ways opened by conspirators.

But in Prince Caspian, we learn of the tyranny from various angles. In this “Return to Narnia,” a remnant of Old Narnia tells the successor to the tyrannical throne—the Telmarine Prince Caspian himself—about Narnia’s long history of loss and suffering under tyranny. We hear the stories of oppressors and the oppressed as old Narnia comes alive again in an alliance of settlers and indigenous peoples.

Prince Caspian’s peculiar position of colonial power in sympathy with the colonized invites us to reimagine Lewis’ fiction in a context where we are coming alive to the stories of lands and their peoples that where often destroyed or forced underground in what Lewis called the death-consumed “social sewerage system” of European colonial rule. Lewis gives space to the heart-breaking tales of the indigenous folk, like Dr. Cornelius, without pretending that colonial systems of government and social development can simply be uncreated.

In this paper, I walk beside Prince Caspian as he considers his role in the ancestral and ongoing (though illicit) land of the Narnians, while I live in the ancestral and ongoing territory of the Mi’kmaq people of Prince Edward Island. Europeans came and conquered, driving the Old Islanders, who once had the wealth of all of these lands and rivers and woods, into tiny hamlets, claiming to rule this place, re-educating the people, and, like the Telmarines, suppressing the old stories and wild ways of being in the world. Without ignoring the cultural distance of time and space between my kitchen table and C.S. Lewis’ writing desk, Lewis helps us reimagine a way beyond course binaries that dominate (especially American) social discourse—guilty and innocent, ignorance and knowledge, despair and naivete—and invites us to listen, live, and lead in transformational ways within the tensions of our ever-changing colonial spaces

Prince Caspian, hungry for magic, mystery, and meaning, thrills when he discovers that “All you have heard about Old Narnia is true. It is not the land of Men. It is the country of Aslan, the country of the Waking Trees and Visible Naiads, of Fauns and Satyrs, of Dwarfs and Giants, of the gods and the Centaurs, of Talking Beasts.” But then he discovers that “It is you Telmarines who silenced the beasts and the trees and the fountains, and who killed and drove away the Dwarfs and Fauns, and are now trying to cover up even the memory of them.”

Brenton, I will remind you of something you know. Importantly, C.S. Lewis was raised as an Englishman living (through childhood) as a colonialist in Ireland. Protestant versus Catholic. English / Norman / Cromwellian Puritan versus indigenous Irish. Tolkien was aware of this, thinking of Lewis as an Ulsterman — a Protestant of North Ireland. An enemy of Rome.(Lewis was never an enemy of Rome, of course, but Tolkien had his priest-advisors.)But I don’t think Lewis ever reflected on his heritage as an interloper in Ireland, as a Catholic realm or an older pagan culture.Lewis was resolutely Medieval, orientated towards remnants of Medieval Europe (and the Roman and Greek pre-Christian cultures and beliefs that lay behind that, and the Northern-ness that stirred him profoundly), with little sense of “Ireland”, conquered and oppressed by the English, his family’s people.Again, I’m sure this is something you have pondered for years.Best wishes for the coming lectures, and projects, virtual and face-to-face.

LikeLike

I like that phrase, “enemy of Rome,” here in Prince Edward Island, the Roman Catholic/Protestant divide was essential, and at times violent. Yet, there was a sense of the community trying to work with it or move past it. Yes, I have thought of these things, but I remain too ignorant of the inner feeling of the history in the Irish isles. I also have this anti-English thing in me (as a Scot) and a love for English literature and history. I don’t know where it all goes.

Of course, I don’t have to know everything!

Also, I have begun Elizabeth Goudge’s The Little White Horse. Delightful!

LikeLike

Excellent thanks, Brenton. Anti-English (as a Scot, by origin) would sit awkwardly beside Lewis’s hearty English pub and holiday rambles and “Logres” in “That Hideous Strength” (although the Pendragon is Welsh, like Perceval; and Arthur’s Logres has Cornish and Scottish — Gawaine — too), and all the rest of Lewis’s stalwart Englishness. But I am sure you know this well, like the White Queen in “Through the Looking Glass” who has sometimes believed six impossible things each day (anticipating Douglas Adams’ “electric priest” by about a hundred years — but that is another story).

Ah! Elizabeth Goudge’s “The Little White Horse”. You have a good memory: I don’t know how long ago I suggested Goudge as an interesting author.

I hope you will share your thoughts about Goudge and this book when you finish.

Happy reading!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I also hope that Brenton will write about The Little White Horse. I read it to my children when they were young and fell in love with it myself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Stephen, for your thoughtful replies.

On the topic of Elizabeth Goudge and “The Little White Horse”, and other novels by Goudge, you and Brenton (when he has finished reading it), may be interested in my article on Christianity in “The Little White Horse” at Academia.edu: and I have other articles on “The Little White Horse”, and on other Goudge novels. I find her a fascinating and deeply satisfying author. Always engaging, but not always easy to understand.

Gough, J. 2024. “Christianity in Elizabeth Goudge’s The Little White Horse”: published online:

https://www.academia.edu/117468044/Christianity_in_Elizabeth_Goudges_The_Little_White_Horse

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much for this. I look forward to reading your article. By the way, as well as The Little White Horse I also have considerable affection for The Dean’s Watch.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Again, thank you, Stephen. I wonder now what other books by Elizabeth Goudge you have read, apart from “The Little White Horse” and “The Dean’s Watch”? These are, as you know, both historical novels, set at different times in the Nineteenth century in different parts of England, “TLHW” in the West country (Devon, notably), and “TDW” in the east of Cambridgeshire, in fen country. But, as you know, “TLWH” has a lot of fantasy, whereas “TDW” is realistic, in the manner of Dickens, Hardy or Hugo.

LikeLike

As I read Brenton’s excellent piece I found myself going to a similar reflection to your own. On my mother’s side my ancestry is largely Ulster Protestant, her maiden name, Foster, being the same surname as a recent First Minister of Northern Ireland. I listened last week on YouTube to a very thoughtful interview on what would need to be addressed if Ireland were ever to be reunited and a major part of this centred around the future of the Protestant population of Ulster. How could they become a full part of a united Ireland and yet remain distinctively themselves? I find Prince Caspian the Narnian story to which my thoughts turn more than any other, usually on the matter of re-enchantment, now I have another layer of reflection to deal with. Was this the closest that Lewis ever came to tackling his own settler, Telmarine, identity?

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a sweet conversation! There are so many threads and approaches, which is why I continue to approach it less as a definitive study but more as an opportunity for conversation.

I wonder: Did Lewis feel more at home in Belfast or Oxford? My sense is that Belfast was his atmospheric home: the Northernness of windswept knolls and mountainsides, sea and land, the people and towns with markets and machines, houses up on hills with many rooms…. But isn’t there something of Oxford that is a forever home for Lewis?

So I don’t know if Lewis felt like a Native of Belfast like I do of Prince Edward Island. I also don’t sense that his family’s move to Ireland was, by necessity, a displacement in the way that the English and French story played out here in Eastern Canada as oppossed to Singapore, India, Kenya, and the like. His family’s move to Ireland was migration within the British isles, while my family’s move to PEI was part of the great adventure, the colonial sweep of the world.

What I can say, though, is that Prince Caspian is a stunningly empathetic tale of Indigenous peoples. Lewis’ tales speak to the resistance against tyranny, but Prince Caspian puts it in such an intimate context that it is hard not to parallel it with the story of First Nations peoples of Turtle Island. How would Lewis then turn that story’s eye upon Ireland?

LikeLike

I’v heard of C.S. Lewis. He was a good author, my favorite of his series’ is the Narnia series.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Uh-oh, I had better reread Prince Caspian! For, “All you have heard about Old Narnia is true. It is not the land of Men. It is the country of Aslan, the country of the Waking Trees and Visible Naiads, of Fauns and Satyrs, of Dwarfs and Giants, of the gods and the Centaurs, of Talking Beasts” astonishes me as a reader of The Magician’s Nephew. There, Narnia is as much a “land of Men” – of Queen Helen and King Frank – as of “the Waking Trees and Visible Naiads, of Fauns and Satyrs, of Dwarfs and Giants, of the gods and the Centaurs, of Talking Beasts” – perhaps even more so of Frank as he is there before any of those other creatures – and ‘permissively’ of a Charnian suffering from libido dominandi (to borrow a term from St. Augustine). Again, “the country of Aslan” – so, of the Ascended perfectus homo (to quote the “Confession […] commonly called the Creed pf Saint Athanasius” as the Book of Common Prayer describes it) appearing in Leonine form.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, beautifully put.

LikeLike

Thanks! Before arriving here yesterday I was reading a Dutch translation of the Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis and ran into a passage which got me wondering if Lewis might be playing with it in Perelandra as well as in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader – Denis O’Donoghue has this translation from Chapter XI on page 154 in his Brendaniana (1895):

“St. Brendan set sail from the island, and when mealtime had come, he told the brethren to refresh themselves with the grapes they got on the island. Taking up one of them, and seeing its great size, and how full of juice it was, he said, in wonder : ‘Never have I seen or read of grapes so large.’ They were all of equal size, like a large ball, and when the juice of one was pressed into a vessel, it yielded a pound weight. This juice the father divided into twelve parts, giving a part every day to each of the brethren ; and thus for twelve days, one grape sufficed for the refreshment of each brother, in whose mouth it always tasted like honey.”

Now, this post – and the comments – have got my thoughts ‘percolating’ like wild. For instance, what-all (ancient and mediaeval) Irish literature did Lewis read, and at what point(s) might he have considered himself an heir of pre-Christian Irish tradition (e.g., after he ‘broadened his mind’, as he puts it in Surprised by Joy)?

And there is the fascinating matter which Tolkien’s Dutch Celtic-scholar friend, Maartje Draak, discusses in her 1962 essay, “Migration over Sea” (and elsewhere) – did the Celts who ended up the Irish migrate to the island, and who (if anyone, still) and what did they find there, and how did it affect their thinking and mythology? For example, she’s not convinced the Irish had ‘gods’ or a ‘cultus’, though they had ‘sacral kingship’ and magic and ‘druids’ (a term she tries to ‘unload’ from all sorts of assumptions) and síd.

And there are all sorts of interesting aspects of ‘Anglican’ compared and contrasted with ‘Roman’ Catholic. For instance, by the ‘our-world’ time of the creation of Narnia, the Catholic hierarchy had been restored in the UK, and there were all sorts of ‘Protestant’ Churches, and some Greek Orthodox ones, and people who had never been baptized. Do we have any idea what Frank and Helen were? – or Digory, Polly, or Andrew, for that matter? Were any or all baptized into the Body of Christ? And what of the first ancestors of the Telmarines – presuming they entered later than those five? Or, again, of those of the Calormenes – who ended up polytheists? Jadis apparently manages to ‘mythologize’ humans – yet at least some Talking Animals know of Father Christmas.

Come 11 December, it will be 100 years ago that Pius XI instituted the Feast of Christ the King – and in the terms of The Magician’s Nephew, Christ is King of all worlds – and the Wood between. But – in comparison to and contrast with Tolkien’s Númenor – there is no cultus and Frank and his successors are not obviously ‘priest-kings’ even in the Númenórean sense. On the other hand, “the Waking Trees and Visible Naiads, of Fauns and Satyrs, of Dwarfs and Giants, of the gods and the Centaurs, of Talking Beasts” know (of) Aslan as the Elves know of Eru Ilúvatar – and as the “mannikin with hooked snout, horned forehead, and extremities like goats’ feet” whom St. Antony meets on his way to visit St. Paul the Hermit in St. Jerome’s Life of the latter, who says “I am a mortal being and one of those inhabitants of the desert whom the Gentiles deluded by various forms of error worship under the names of Fauns, Satyrs, and Incubi. I am sent to represent my tribe. We pray you in our behalf to entreat the favour of your Lord and ours, who, we have learned, came once to save the world, and ‘whose sound has gone forth into all the earth'” (as translated by W.H. Fremantle, G. Lewis and W.G. Martley).

LikeLike

Also intriguing in this context, is something Maartje Draak’s successor at Utrecht, Doris Edel, says in her contribution to De Wereld van Sint Brandaan [The World of St. Brendan] (1986) about a special form of Sixth-century Irish asceticism: ‘that one left one’s own familiar, trusted surroundings to serve God in foreign places..’ In this ‘peregrinatio pro Deo (‘pilgrimage for God’)’, the peregrinus (‘pilgrim’) […] gave himself up to voluntary exile for many years, often for the rest of his life’ and they also called this ‘white martyrdom to distinguish it from red martyrdom, being tortured to death’ (my translation).

LikeLike

Pingback: Can C.S. Lewis and L.M. Montgomery be Kindred Spirits? My CSLKS Conference Talk in Iași, Romania | A Pilgrim in Narnia

I remember reading that all Gothic literature had certain features in common; specifically that nearly all of the authors were Protestant and colonial and that Gothic Literature was an attempt to process what this actually meant – a sense of being besieged, the possibility of one of your own ‘going native’ etc. Very often (or so I suspect) these authors weren’t aware of what they were doing. Maybe Prince Caspian is a case in point?* So whereas Lewis the Ulsterman might balk at the idea of supporting Irish revolutionaries, Lewis the Author had the freedom to see the situation in a completely different light.

LikeLike

Prof. Dickieson,

I’m not sure if this will give you the angle you’ve been looking for to put your thoughts on Colonialism, Indigenous Spaces, and what makes the Human Being an Hnau, however it might give help, with any luck. Have you by chance heard of a book called “C.S. Lewis on the Final Frontier”, by Sanford Schwartz?

If the answer is no, then I think I’d better turn over the description of the book’s content to Prof. Sorina Higgins. She does a better job of telling all about it. According to her review of the study for “Sehnsucht”, “Lewis did not hesitate to engage with the scientific hypotheses, philosophical assumptions, and socio-political concerns of his time; neither does Schwartz; neither should any thinking Christian. What is fundamentally an historical investigation of Lewis’ modernism proves, as an unconscious corollary, that literary criticism has resonance and relevance outside the ivory tower. Lewis listened to the ideas of his time, transformed them in his fiction, and has the potential to transform the ideas of our time. Such a revolution could help heal divisions within the church and wider Christian culture. In the introduction Schwartz writes, “Elwin Ransom’s three-volume transformation from terrified victim to anointed guardian of the planet bears the unmistakable imprint of the violent conditions of the time.” Such a change is imperative, again, now, outside the pages of fiction.

“Lewis’ transformational, or “transpositional” power,3 is the foundation of Schwartz’ complex and compelling thesis. Actually, he proposes three interrelated theses: first, that the three volumes of the Ransom trilogy are built on the same narrative structure of concentric rings; second, that each volume parodies, in the person or place of the antagonist, a particular evolutionary model; finally, that each volume goes beyond mere criticism or parody to postulate an ideal archetype of which each evolutionary model is the distortion. This last facet of the thesis— that “Bad things are good things perverted”4—is manifestly the most difficult to understand, but Schwartz explains and defends it with deft confidence. This threefold view of the Trilogy has a remarkable effect: looking at Lewis primarily as a modernist supersedes nearly all previous studies of the Trilogy. Schwartz’ comprehensive, contemporary approach brushes aside the medieval, Renaissance, and Neo-Classical interpretations of the Trilogy and replaces them with something so recent, so relevant, that we can reach out and touch it with our twenty-first century minds. Lewis’ explorations of theology, science, time, and space, and what it is to be human (or hnau) overlap almost continuously with the ongoing explorations of our own century. A fairly detailed summary of Schwartz’ arguments here is essential for understanding his book, and should prove helpful once a reader turns from this review to the text itself“.

A key piece of her review, the one that seems relevant to the ongoing theme you’re looking for, comes from the way “Out of the Silent Planet” functions as a Scientifictional form of satire. “The presentation of Weston and Devine interrogates Imperialism and Colonialism, much as Wells’ War of the Worlds forty years before had parodied human colonization in that of the ruthless Martians. Similarly, this first volume of the Ransom Trilogy challenges racism and the exploitation of other rational beings. However, Lewis goes beyond Wells’ materialistic biocentrism to propose that reason is a spiritual gift. Rationality enables us to combat anthropocentrism and (counterintuitively) recognize our kinship with the beasts based on our shared embodiment. Furthermore, Lewis imagines a possible social harmony among races and species undreamed-of in Wells’ philosophy. This foresight allowed Lewis to see into the future, as well: Out of the Silent Planet as seen through Dr. Schwartz’ eyes contain surprisingly clear prophecies of the rise of Nazism, the resulting racial genocide, and—most apropos—the ongoing experimentations in eugenics that continue to plague the twenty-first century: ‘Lewis is linking the violent legacy of traditional imperialism to the new ideology of militant racism, especially virulent after the Nazi rise to power, which would soon lead to global warfare on an unprecedented scale and a genocidal campaign of unimaginable savagery”.

Like I say, I can’t tell whether this is the missing angle you’re looking for. It just sounded like a good source text for a sounding board. The best I could offer on my own account might go as follows. If you want, you might add a final ingredient to your thesis. That being Karl Popper’s concept of the Open Society. It “might” be useful as a way of maybe completing the picture by positing Lewis’s uses of the Secondary fictional versions of Mars and Venus as “supposals” of what such societies might look like. If the addition of Popper to the mix sounds like an off-note, then apologies all around. I merely suggested “The Open Society” as a possible helpful source because apparently Lewis kept an annotated copy of Popper’s landmark study in his personal library. This is something I found out by looking into the Wade Center’s Author Libraries. It’s one of those intriguing hints about the direction Lewis’s thought might have been taking in the Postwar Years. It’s been suggested that CSL might have found a cautious amount of common ground with Popper anti-Historicism and anti-Positivism. Adding Schwartz’s thesis of the “Ransom Cycle” as an attempt at combating the kind of fascistic Colonialism of his own era might make for a neat (albeit precarious linking point) between these two thinkers, one that might help sharpen whatever academic clarity is needed in the Field of Hnau Studies, to suggest a useful title. Prof. Higgins’ revies of the Schwartz study can be here linked below, by the way:

https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/cslewisjournal/vol3/iss1/8/

LikeLike