This is an honest question that I hope readers can help me with, and a proposal I would like to test out. C.S. Lewis’ second space travel adventure, Perelandra, begins like this: “As I left the railway station at Worchester….” It just occurred to me to find out where that station is (or was).

This is an honest question that I hope readers can help me with, and a proposal I would like to test out. C.S. Lewis’ second space travel adventure, Perelandra, begins like this: “As I left the railway station at Worchester….” It just occurred to me to find out where that station is (or was).

As far as I can tell, Worchester spelled thusly is not a place we would have found in WWII England. There is a Worcester College at Oxford, the alma mater of Emma Watson and Richard Adams—a fact that probably is more interesting to me than to Lewis. Lewis had a friend named Wyllie at Worcester while he was attending Oxford as a student. Lewis had once been given a pair of swans by the Provost of Worcester College, which he hated—the swans, not the Provost. Still, not a terribly strong link.

There is a Worcester in Worcestershire, England—a small city I passed by last year on my way from Birmingham to Cheltenham to visit friends. There are random historical events that are set in Worcester that Lewis might have found significant. Tyndale appeared for charges of heresy there in the early 1520s. Hugh Latimer was Bishop there 1535-39 when he resigned to take up being a heretic full time. Most significantly, the Battle of Worcester closed the English Civil War as Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentarian army defeated King Charles II’s Royalist and Scottish army. Worcester was also plan B for the Parliament in WWII in case London had to be abandoned, though I doubt if Lewis knew that.

And, of course, there is the Lea & Perrins brand of Worcestershire sauce, an ill-used staple in our home and many others, I am sure.

And, of course, there is the Lea & Perrins brand of Worcestershire sauce, an ill-used staple in our home and many others, I am sure.

Perhaps the link is more personal. Lewis and his brother Warren spent a good deal of time at the schools of Malvern College, which is in Worcestershire. It is where C.S. Lewis abandoned his Christian faith, as he describes in Surprised by Joy and therein calls his school Wyvern College. This was not a warm place in Lewis’ memories, though he had friends, and he would have gone to the city of Worcester for enjoyable outings (escapes) from school.

Of all these, the links to Ransom’s world are not terribly clear. The strongest one is the Battle—and that link might not be more than tangential. Let’s walk through them.

In Perelandra, Lewis the character-narrator gets off at the Worchester station to go to Dr. Ransom’s cottage in the first lines of Perelandra. Ransom is a Cambridge philologist at the fictional Leicester College. If Worchester is Worcester–the misspelling is made with frequency and my audiobook pronounces it like the latter spelling–then the commute from Worcester to Cambridge would be unusually long—at least four hours. The reason that Ransom isn’t home when Lewis gets there is because he had to slip up to Cambridge. There is now a West Chesterton district in the suburbs of Cambridge, but I doubt that is the fictional town in view. Lewis did end up commuting from Oxford to Cambridge, which might have been a three-hour trip, but this wasn’t until more than a decade after Perelandra was written.

Is Worchester meant to be the Worcester of Lewis’ youth? Most of the geographical set up of the Ransom Cycle is fictional. In Out of the Silent Planet, the hiking villages of Nadderby and Sterk are not (unfortunately) real places where a philologist could have walked in the 30s. St. Anne’s in That Hideous Strength is not the end of any line I know (though there is a St. Anne’s College not far from Worcester College in Oxford). Among early readers or the Inklings, there may have been conjecture that Lewis was veiling real places in THS. It seems some thought Lewis’ Town of Edgestow and Bracton College were related to Durham:

A very small university [in That Hideous Strength] is imagined because that has certain conveniences for fiction. Edgestow has no resemblance, save for its smallness, to Durham—a university with which the only connection I have ever had was entirely pleasant (Preface to That Hideous Strength).

The fiction of Edgestow is filled out with a number of scenes in the text and with a college that has a deep history that roots the story:

Though I am Oxford-bred and very fond of Cambridge, I think that Edgestow is more beautiful than either. For one thing it is so small. No maker of cars or sausages or marmalades has yet come to industrialize the country town which is the setting of the University, and the University itself is tiny. Apart from Bracton and from the nineteenth-century women’s college beyond the railway, there are only two colleges: Northumberland which stands below Bracton on the river Wynd, and Duke’s opposite the Abbey. Bracton takes no undergraduates. It was founded in 1300 for the support of ten learned men whose duties were to pray for the soul of Henry de Bracton and to study the laws of England (ch. 1).

If Edgestow is fictional, there are some real English reference points in THS. Oxford is added to Cambridge as real universities, and there is also London, Lancaster, and, as we see below, York in the north and Warwickshire, on the borders of Worcestershire. Belbury, which houses the evil N.I.C.E., is fictional. But Belbury and Edgestow must be within a difficult walking distance of Worcester, as N.I.C.E.’s forced exodus has driven “driven two thousand families from their homes to die of exposure in every ditch from here to Birmingham or Worcester.” We also find out that St. Anne’s is on the way to Birmingham when Jane is saved from a riot in ch. 8 and as Mark tries to stumble towards his wife in ch. 17.

As mentioned above, the clearest link to the historical area of Worcester is to the Battle of Worcester that ends the reign of Charles II. It is captured here in this dialogue with Jane and Miss Ironwood at St. Anne’s Manor, as Jane is slowly discovering she is a seer—a thing she doesn’t believe in:

“What was your maiden name?” asked Miss Ironwood.

“Tudor,” said Jane. At any other moment she would have said it rather self-consciously, for she was very anxious not to be supposed vain of her ancient ancestry.

“The Warwickshire branch of the family?”

“Yes.”

“Did you ever read a little book—it is only forty pages long—written by an ancestor of yours about the battle of Worcester?”

“No. Father had a copy—the only copy, I think he said. But I never read it. It was lost when the house was broken up after his death.”

“Your father was mistaken in thinking it the only copy. There are at least two others: one is in America, and the other is in this house.”

“Well?”

“Your ancestor gave a full and, on the whole, correct account of the battle, which he says he completed on the same day on which it was fought. But he was not at it. He was in York at the time” (ch. 3).

How do all these individual links connect?

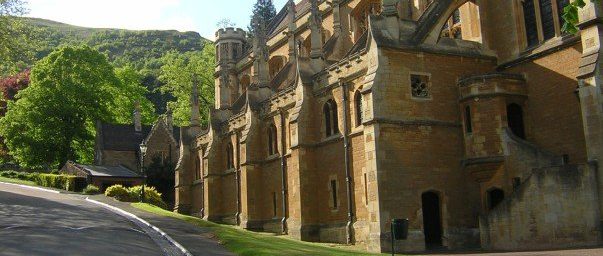

My proposal is this: That Lewis’ fictional Edgestow is in a small town (2000 people or fewer) in the real Worcestershire, and that That Hideous Strength is likely set in a fictionalized campus like Lewis’ own Malvern College, which is about 10 miles southwest of Worcester in Worcestershire. I will explore a few connections which leads me to this idea.

Lewis loved the architecture of Malvern, and was delighted by the “great blue plain below us and, behind, those green, peaked hills, so mountainous in form and yet so manageably small in size” (Surprised by Joy ch. 4). THS is filled with small English villages, college buildings, large hills, open fields, and ancient woods. Great Malvern and Malvern Hills is a good fit for the novel, though many other places would do as well.

Pressing in on distances, if one was a N.I.C.E. exile pulling a farm cart or a wheelbarrow full of one’s possessions—”chests of drawers, bedsteads, mattresses, boxes, and a canary in a cage”—Great Malvern would be a long day’s walk to Worcester. Birmingham would be two or three days further at the pace of an exodus as one reads in H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds–the image doubtless at the back of Lewis’ exiles in THS. Moreover, a train from Edgestow to St. Anne’s would follow a Birmingham direction from Malvern (or any number of nearby places).

Malvern, then, transformed into a late medieval university instead of a Victorian school (with its nostalgic architecture), could be the setting. Great Malvern, before its post-war renovations, would have had a lot of the features of the classic English village of Edgestow. Particularly intriguing is the St. Anne’s Manor in THS. Great Malvern–the town connected to Lewis’ boyhood schooling–is home to St. Ann’s Well, which has a cafe attached to its spring water well named after Saint Anne, mother of Mary. The inclusion of Merlin’s Well and St. Anne’s Manor in That Hideous Strength makes a pretty interesting connection to Great Malvern.

If Malvern is the site of Edgestow and Bracton College, and Worchester is Worcester, it also means that Ransom’s move to St. Anne’s Manor at his sister’s will would have been a relatively simple one. He would have merely moved from his cottage in Worcester city–which would be about a half hour walk from the main station–to an estate a few trains stops that side of Great Malvern.

If all of this geographical speculation is remotely plausible, the really critical question remains: Would Merlin’s resting place be in Worcestershire?

That’s hard for me to answer. While Merlin is probably from Welsh origins—and Malvern isn’t far from the border of Wales—I would expect Merlin to be asleep in Broceliande. Where would that be? Bookies would say to put your money on Brittany, and the French tradition of the Matter of Britain is critical.

Clearly, though, Brittany would not suit Lewis’ purposes in his modern English Arthurian tale. It is a peculiarly English apocalypse (as is H.G. Wells’ apocalypse fifty years before). Oxfordshire and Worcestershire are not far from the legendary downtown Logres, and almost any historic place of interest south of there has a claim of being Camelot. Wales is not that far away, and I have heard the area north of there called “Merlin’s Land” (though I don’t know why).

Could Malvern as Edgestow be where Merlin has been secretly asleep for centuries? It’s possible, and Merlin’s waking is distinctly Lewisian in THS, and pulls at the threads of the Arthurian garment in more ways than just geography.

Unfortunately, I cannot tell more from the details. Most of Lewis’ connections with the area are later. Lewis walked in Great Malvern at various times in his adult life, including a tour with J.R.R. Tolkien. George Sayer was a friend of Lewis’ and his biographer, and he was head of English at Malvern from 1944–Sayer got the post as Lewis was editing THS (the draft was complete the previous December). And, of course, we don’t know how clear in his own mind Lewis had the geography of the Ransom Cycle in place. Perhaps he was just making it up as he went along.

Unfortunately, I cannot tell more from the details. Most of Lewis’ connections with the area are later. Lewis walked in Great Malvern at various times in his adult life, including a tour with J.R.R. Tolkien. George Sayer was a friend of Lewis’ and his biographer, and he was head of English at Malvern from 1944–Sayer got the post as Lewis was editing THS (the draft was complete the previous December). And, of course, we don’t know how clear in his own mind Lewis had the geography of the Ransom Cycle in place. Perhaps he was just making it up as he went along.

The use of Worcester does seem striking, though. The claim that the action of That Hideous Strength takes place around Malvern–the college, Great Malvern, the evocative hills, with train and exodus lines to Worcester and Birmingham–is a good one.

Still, now it’s your turn: What do you see in the tale? Is there a significance to Worc(h)ester? Or are the geographies drawn variously to obscure a non-location for the tale—or intentionally hidden, as per the conspiracy intimated at the end of Out of the Silent Planet or Michael Ward’s Planet Narnia thesis? I would love your thoughts.

As an afterthought, and certainly no link in C.S. Lewis’ mind, is the College Grace (which is the same as Christ Church’s long-form grace. It is always given in Latin, but here is the English translation I took from Wikipedia. You “unhappy” isn’t the right word, it strikes me as a good Ransom Cycle prayer, with its request for the heavenly food that brings true sustenance:

“We unhappy and unworthy men do give thee most reverent thanks, Almighty God, our heavenly Father, for the victuals which thou hast bestowed on us for the sustenance of the body, at the same time beseeching thee that we may use them soberly, modestly and gratefully. And above all we beseech thee to impart to us the food of angels, the true bread of heaven, the eternal Word of God, Jesus Christ our Lord, so that the mind of each of us may feed on him and that through his flesh and blood we may be sustained, nourished and strengthened. Amen.”

Fascinating. My wife and I visited George Sayer in Malvern in 1993, He and Margaret were gracious hosts. We shared sherry in the parlor where he recorded Tolkien reading poetry from the then-unpublished “The Lord of the Rings” and the riddle scene from “The Hobbit.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s very cool, Mike! I didn’t know the provenance of the recording either. I’ll pop in on the Sayers next time I’m there. 😉

LikeLike

Many thanks for this tour de force, Brenton! I am writing this just a few miles north of Worcester in our cottage that sits on the banks of the early 19th century canal that links Birmingham and Worcester and by the Roman road that linked the salt meres of Droitwich and the fort at Alcester. The winter sun has just set through the mists quite spectacularly and now the long night begins.

My family and I moved out of the city of Birmingham in 1998 into this county of Worcestershire and we have grown to love it over the years. I have long connected this county with Tolkien’s Shire, after all there is a farmhouse just a few miles to the east of here that once belonged to Tolkien’s aunt, Jane Neave, and which was called, Bag End. Now you have given me a wholly new area of local research through That Hideous Strength. I am so grateful!

I once preached in Malvern College chapel and enjoyed a delightful conversation after the service with a young man who had just found Christian faith, unlike Lewis who lost his there. I just made a prayer for him. He must be in his early 30s now amidst all the cares of life. It was good to be reminded of him.

My wife and I have been slowly making a circuit of the county along public footpaths when her busy life as a family doctor and a mother permits. The Malvern Hills are a significant part of it but there is much more that is beautiful. The shape of the county is formed by the River Severn that flows through Worcester and its plain surrounded by a ring of hills of which the Malverns form a part. A short walk from our cottage takes you to a hill top chu

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Stephen, that is a beautiful description. Birmingham did not strike me–except as a place to change trains–and I understand why you moved. And we would love to visit on our next step inside the country. I would like to hike more next time.

Next time you read THS, see if you can imagine your countryside in the back of the tale.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoyed living and working in Birmingham for 10 years. I met my wife there and our daughters were born there too. But I love living here.

I will read THS with care next time and I hope to be able to extend hospitality to you the next time you are in England.

Merry Christmas!

LikeLiked by 1 person

…Hill top church that was once the site of an Anglo-Saxon monastery and affords a wonderful view across the county and on a clear day right to the Welsh border and its hills.

When you are next in the country please drop in. We have plenty of room for guests and I would love to explore the county from the perspective that you offer here. I might even have made one or two discoveries of my own by then!

PS please excuse the inadvertent sending of my first comment in mid sentence. I got carried away with over enthusiastic typing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is some detective work! It’s like Lewis’s creative process treated the real world as a kaleidoscope. To create a fictional world, he would twist it so all the colored bits fall into a different arrangement, but an industrious scholar can trace each one back to its original position.

LikeLike

Thanks Joe! I like the idea of the kaleidoscope. I would like to think through some metaphors for that project and see which ones fit.

LikeLike

There’s a Worcester in Massachusetts, FYI and is locals say it like this “Wuster” not like the condiment.

LikeLike

Yes, that’s how they say it! I’ve been by Worcester every couple of years for the last decade, but have never lingered more than a hotel stay.

LikeLike

There’s a Worcester in South Africa too. I know it mainly from passing through it, and once spent a night there when the vehicle I was driving had caught fire, and the lights had burnt out, so I was was caught by nightfall and forced to stay the night. The most memorable feature of that town, in my mind, is the irrigation furrows that run down the streets. Its name, like the English one, is pronounced “Wooster”. I’ve never been to the English one., though I have travelled by train from Oxford to Birmingham when on my way to Durham, where I was studying.

I suppose I’ve always pictured Bracton college as being somewhere in the English Midlands, and thought of the setting as somewhere north of Oxford. In thinking of C.S. Lewis’s fictional places, I haven’t often tried to think of them as real places, and I regard his choice of fictional names as similar to those I made in a children’s novel I wrote. It was set near a fictional town called Pineville, in the foothills of the Southern Drakensberg of South Africa. There are two real towns nearby, Himeville and Underberg. The trouble with small towns is that people tend to know each other, and if you set a story in a real town, people will try to identify the places and characters. So Pineville was fictional, and a composite. It had features of several small towns I had known. It had a church, which in my mental image resembled one in Ladybrand, a bigger town a couple of hundred miles away.

So I imagine Lewis was thinking in much the same way. He may have had pictures in his head, but they would be a composite of many places he had known. And his Worchester was perhaps like Trollope’s Barchester. And I think he left it up to the reader to fill in the picture.

I sometimes dream about places, but the dream places are often quite different from the real places, yet they are consistent from dream to dream, and even while dreaming I am sometimes aware that the geography of the dream town differs from the town of the same name in waking life. Perhaps Lewis had similar dreams, and drew on his dream memories for his fictional towns.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Steve, as a follow up to the last note, it actually says in THS that it is set in the Midlands.

LikeLike

I also dream about real places differently than they actually are! I wonder if this is a common phenomenon? I also read text in dreams which is apparently rare.

LikeLike

I know nothing about South Africa! To be fair, I have always suspected people outside of North America know as much about Canada. There is “Wooster” in the US, but it is more like “Woystah,” I think.

I have used one village in my writing, quite clearly and specifically (but with a fictional name). And in an urban book I’ve used Vancouver, as well as Chicago and DC elsewhere, all stripped of specific feature.

The Barchester approach is probably right, though I’d still like to walk through the Malvern hills for myself….

LikeLike

Fascinating! Many thanks for embarking on this!

I wonder if (a sort of folk-)etymological wordplay has any part here? – I say, having never before twigged to the ‘-vern’ in ‘Wyvern’ playing with the ‘-vern’ in ‘Malvern’ till this moment (duh)!

E.g., could Ransom’s ‘Worchester’ play with ‘Grantchester’, which is quite near Cambridge? But would the ‘Wor-‘ then just be realistic-sounding, or have some wordplay significance? Presumably the ‘ch’ would mitigate against it being pronounced ‘Wooster’. (You reminded us not so long ago of Lewis’s awareness of the ‘wor-‘ in ‘world’ as deriving from ‘wer’ (man)…: upon which, quite possibly for no good reason, Bunyan’s The Holy War Made by King Shaddai Upon Diabolus, to Regain the Metropolis of the World, Or, The Losing and Taking Again of the Town of Mansoul (1682) springs to mind…)

The history you quote for Edgestow makes me think not only of the histories of the growths of both Oxford and Cambridge Universities in those respective formerly smaller places, but also of the idea that if things had gone a bit differently, Stamford (in Lincolnshire) might have ended us like Oxford,and Oxford like Stamford – though I don’t think he can intend Edgestow to be a fictional version of Stamford (which is nowhere near Birmingham…) – in any case, he interestingly imagines the phenomenon of the place remaining small, despite the growth (however comparatively restrained) of the university.

Might an imaginative element be an extrapolation of Malvern schools to Oxbridge-style colleges? Here, “the nineteenth-century women’s college beyond the railway” sent me searching, and finding four schools, in Lewis’s time: Lawnside, Malvern Girls’s College, the Abbey School, and St. James’s School… Do Eton and King’s offer interesting matter for comparison, here? (Incidentally, “Bracton takes no undergraduates”: what other colleges resemble this, beyond All Souls’?)

What of Henry de Bracton and geography? Recklessly relying on Wikipedia, I see he was born in Devon, buried in Exeter Cathedral (of which he was chancellor), got around a lot, notably “in the southwestern counties, especially Somerset, Devon and Cornwall”, and “established a chantry […] for his soul that was endowed from the revenues of the Manor of Thorverton”, Devon.

As to Merlin’s grave, I note having searched at Edward Watson’s site Clas Merdin for that, this was the first of several posts the search led to:

http://clasmerdin.blogspot.nl/2009/07/luds-church-xiv.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

Goodness! I hadn’t thought of de Bracton in history. There you go–but not in the midlands, where the story is set.

The rest still keeps me near “Wooster.” A friend from church grew up there (I didn’t know) and read this post and thought that I was on the right path.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Speaking of place-name wordplay, of ‘Belbury’, Arend Smilde includes among his THS notes at Lewisiana, “According to Joseph Pearce in C. S. Lewis and the Catholic Church (2003), p. 93, this might be a play on the name of Blewbury, a village some fifteen miles south of Oxford. While Lewis wrote the Ransom trilogy, controversies were going on over the foundation of an atomic plant near Blewbury. In 1946, the Atomic Energy Research Establishment (AERE, or “Harwell Laboratory”) was opened at the former RAF base of Harwell, near Blewbury. This was the site of the first nuclear reactor in Europe.”

I feel sure I have seen suggestions that the ‘Bel-‘ of ‘Belbury’ plays with it as a form/derivative of ‘Baal’, as, for example, in Jezebel.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think the last one is brilliant (not so much the other–the AERE is a hint, maybe). If “bury” is from the same root as ‘burg”, then “the fortress of Baal” is a good name for the headquarters of the NICE.

LikeLike

Wow…love this post. So interesting to see all the connections you have made here. Alas I can offer no further insight but would love to go walking in those Malvern Hills and visit the beautiful Malvern College. Ack. My “must-visit” list for my next trip to England keeps getting longer!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know! I want to wander in that area, so we’ll see if I ever get there.

LikeLike

I’ve never managed to get there (yet) either, attractive as the prospect is! Reading Caught in the Web of Words, I just reached Dr. and Mrs. Murray taking a refreshing break from OED work in the Malvern hills… And, corresponding with Dale Nelson about John Masefield’s Midnight Folk and Box of Delights, got thinking about Masefield and the Malvern area and wondering if those books might have any stated or recognizable geographical references, or what-all those of his Arthurian poetry include (The Midnight Folk is explicitly Arthurian… in significant part, anyway. And what of his Badon Parchments, come to that…) And, browsing around a bit, was delighted to encounter this:

Click to access ALiteraryTrailaroundtheMalverns_000.pdf

George Sayer told me of Lewis’s delight in The Midnight Folk, but I cannot remember with or without reference to when he read it (not before he was 29, when it was published), and Dale draws my attention to Lewis in a 1959 letter to Martin Hooton thanking him for a copy of A Box of Delights (need to look that letter up and read it in full!). Which reminds me of some interesting correspondence I had with Grevel Lindop about Lewis and one or both of those Masefield children’s novels – which I can’t quickly re-find (alas!).

LikeLike

Wow – just noticed… shall we assume they know what they are doing?:

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.208319

LikeLike

Do they ever know what they are doing?

Honestly, I’ve read nothing of Masefield, but this tempts me. Our local library has a paper copy. Bedside reading?

LikeLike

Pingback: Why the C.S. Lewis and Friends Colloquium is Awesome: The Bit About Students | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: The First Meeting of the Inklings by George Sayer | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Off to the UK! | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: What Counts as An Old Book? A Conversation with C.S. Lewis and Goodreads | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Adam Mattern on C.S. Lewis’ Science Fiction (Announcement) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: C.S. Lewis’ Science Fiction with Adam Mattern, David C. Downing, and Brenton Dickieson | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Gods or Angels? A guest post by Yvonne Aburrow | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: How do you Solve a Problem like Susan Pevensie? Narnia Guest Post by Kat Coffin | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “The Country Around Edgestow”: A Map from C.S. Lewis’ That Hideous Strength by Tim Kirk from Mythlore | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: An Old Pictorial Map of Central Oxford (Are There Links to C.S. Lewis’ Fiction?) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Experimenting on Students: A Thought about Playfulness and Personal Connection in Teaching | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: The C.S. Lewis Studies Series: Where It’s Going and How You Can Contribute | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “The 80th Anniversary of C.S. Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters” by Brenton Dickieson | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “Reading Lewis’ Ransom Cycle” a Short Course with Dr. Sørina Higgins and the Signum SPACE Program | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: A Review of Mystical Perelandra: My Lifelong Reading of C.S. Lewis and His Favorite Book by James Como | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “The Saxon King of Yours, Who Sits at Windsor, Now. Is There No Help in Him?” Thoughts on the British Monarchy from “That Hideous Strength” by C.S Lewis on the Death of Queen Elizabeth II. | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “The Saxon King of Yours, Who Sits at Windsor, Now. Is There No Help in Him?” Thoughts on the British Monarchy from “That Hideous Strength” by C.S Lewis on the Death of Queen Elizabeth II (by Stephen Winter) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Very late to the party here but I’d say that Edgestow could be a fictionalized version of Stow on the Wold (which is more or less in the right area). And I wonder if Lewis was inspired to include Worcester because Tolkien loved it so much and made it his fictional city of Kortirion?

LikeLike

Pingback: A Rationale for Teaching C.S. Lewis’ Fiction in The Wrong Order | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Introducing C.S. Lewis’ Unfinished Teenage Novel “The Quest of Bleheris” | A Pilgrim in Narnia