In Mary Poppins’ London, chimneys puncture the skyscape like fenceposts on an English hill. New York’s skyline shattered in our imagination as this 21st century began, and still, the skyscrapers crowd together as if protecting Lady Liberty from the sea. We know Chicago’s lakeside shadow too, though it is acres of suburban clusters in neat little spirals linked with old West grids that organize the eye when flying above. In Paris the Eiffel Tower is the vertical axis of both geography and culture, as are the towers of Seattle, Toronto, and Dubai. Even here in quaint Charlottetown, the spires of St. Dunstan’s arise from the city, like three hands reaching for the heavens.

Oxford’s legendary skyline is a human way to paint the sky. In a poem to a lost friend, Matthew Arnold begins,

“How changed is here each spot man makes or fills!”

It is certainly true that human beings make and fill. Naturally, we shape nature, but then we fill it full to bursting with us, from “The village street its haunted mansion lacks” to “the roofs the twisted chimney-stacks.”

In this way, Arnold walks us into Oxford:

Runs it not here, the track by Childsworth Farm,

Past the high wood, to where the elm-tree crowns

The hill behind whose ridge the sunset flames?

The signal-elm, that looks on Ilsley Downs,

The Vale, the three lone weirs, the youthful Thames?—

This winter-eve is warm,

Humid the air! leafless, yet soft as spring,

The tender purple spray on copse and briers!

And that sweet city with her dreaming spires,

She needs not June for beauty’s heightening, . . . (“Thyrsis,” Selection, 153)

Arnold’s patriotic plan for changing “each spot” with human making and filling has, at times, been horrifying in its presumptions and results. However, there is a reason that his phrase “dreaming spires” seems exactly right. Glimmering steeples, ancient towers, and lanterned domes stand guard over a medieval city in the air. Like stalagmites with vertigo, Oxford’s steeples and pinnacles and gargoyle-guarded cathedral girding have grown with the ages. The skyline is peopled with the ghosts of a Gothic era that Oxford never quite leaves behind. As (now) Dr. Emilie Noteboom said when I first put feet to cobblestones, in Oxford, you must look up.

I don’t know whether Oxford’s dreaming spires are swords of civilization raised in triumph or candles of the penitent trimmed by the gods, but it fills me with imaginative delight every time. I miss it now.

Even in a city of a million peaks and a hundred churches, Oxford’s Christ Church Cathedral is not forgotten. Though the current building is much newer—built in the last part of the 1100s—it is on the traditional site of St. Frideswide priory and a Saxon cemetery. It is a mixture of Norman and Gothic architecture; its cruciform (cross-shaped) stone walls are the foundation for its great hexagonal spire. If you look up at the crossing at the centre of the church, the ribbed vaulted ceiling seems to be in motion, rising up into the central tower. At least, that’s how it felt to me as I followed Emilie’s advice to lift up my eyes in Oxford.

This tower, the church’s ten-petalled rose window, and the Great Quadrangle have shaped and continue to shape Oxford’s visual culture. As a place dedicated to learning and worship, the architects of Oxford structured their spaces in the form of the cross.

But it took me longer to discern another essential feature of Oxford’s literary and spiritual architecture. It began on a Sunday morning.

Depending on your view, I was either very late for the 8:00 Eucharist or very early for the 10:00 Matins. Like a character from Dorothy L. Sayers’ Gaudy Night, the Christ Church porter had one of those bored, “another uninformed American tourist” look on his face as I hesitated. It was 8:50, and I had an hour to kill.

Instead of loitering in the Quad under the porter’s disapproving eye, I found my way to Starbucks on Oxford’s busy Cornmarket Street. In one of the odd synchronicities of life—the saints call this “providence,” and the novelists call it “realism”—Dr. Laura Smit, an American theologian whose work I had read, walked into the coffee shop and said, “You’re Brenton Dickieson, aren’t you?” I was, and still am, and admitted as much. So we had coffee together.

As it turns out, Laura was also early for Matins at Christ Church. I now had a guide to the world of High Anglican liturgy, a sacred multi-sensory space where the body engages in worship as the mind finds the words. It is a world very foreign to me, but one that echoes the pattern of the universe where Word becomes Flesh.

And in another incarnation where the digital becomes analog, I had a friend at Christ Church.

Oxonians believe that in order to explore the multiverse of human and divine knowledge, one needs both space and beauty. The beauty of Oxford’s architecture is enough to break your heart, and I knew that about Europe even before I landed. I even know about the shape of the cross in Oxford’s design.

What I wasn’t expecting was the need for “wasted space,” which in Christian tradition is sacred space.

By its very architecture, Christ Church draws the heart to centre and the eye to the ceiling. The Great Quadrangle, the Tom Quad, is also cruciform. The perfectly manicured lawn and paths crossing centre and circling the perimeter create the shape of a Celtic cross from the sky.

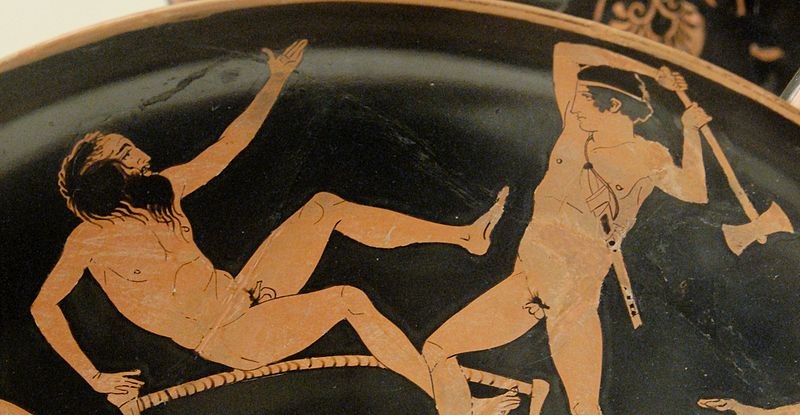

In the famous fountain at the crossing stands the messenger of the gods, Hermes or Mercury, known in the Ransom Cycle universe as Viritrilbia. I don’t know if Mercury is singing odes to the gods, or raising his fist to the sky against them, or ready to launch off to lead heaven himself. I’ve never been able to get my mind around Mercury.

As the porter had directed us, the Cathedral sits at one corner of the Quad. It isn’t often that beauty catches my breath, but this was one moment. From the dark hallway and checkerboard pavingstones, the walk into Christ Church’s marble arches gave the illusion of eternity—or perhaps was meant to give a hint of the reality beyond time and space.

How can I describe this sanctuary? Apostolic scenes in hardwood, columns holding the weight of millennia, an altar of gold, stained glass stories tucked into the transepts—there are times when it is best to point to a digital panorama rather than try to do justice to the aesthetics.

I trip across John Locke’s memorial stone on the floor as the pipe organ fills even the spiderweb rafters with sound. We sit on crushed velvet cushions, softer than the severe wooden pews that were designed to keep one’s mind and morals as straight as Renaissance spines. I do not know if the Bible is resting on a golden eagle or phoenix—each with its own mythic significance—but Scripture is not just for reading in the service. It reverberates in song as the boys’ choir rises to chants, hymns, and the call-and-response pattern that shapes the rhythms of both the body and the spirit.

The scriptures are read, and we kneel. The gospel message and the stories of the saints are evoked in prayer. Song and story, voices and movement, the liturgy becomes one of those incarnations where spirit becomes flesh. While I imagine that I am inhabiting the church, it is that sacred space that is making its home in me. Even for those who come to church in the silence in between these services, the story is told in stained glass, moulded wood, and chiselled stone.

And for those who have eyes to see and ears to hear, the story resonates in the wasted space. Silence, stillness, white space, unfilled margins, form without function, hollow shadowy regions far beyond our reach—Oxford’s theological design is both a fulfillment of and a resistance to Matthew Arnold’s description of the human vocation:

“How changed is here each spot man makes or fills!”

We make and fill. But even in these spots made by human hands—the untrod grass of scholarly quadrangles and the empty rafters of cruciform churches—we do not fill out all the spaces, as is our wont. While wasted space is an ugly blot in our technoculturally designed urban landscapes of map and mind, Oxford reminds us that we cannot—we must not—fill every space with our human making.

We must leave room for something else.

Visual artists know the value of negative space. Filmmakers and preachers know the value of silence and stillness as much as they know light and motion. But when our making is economically refined and utilitarian, architects can get lost in filling space rather than shaping our experience of otherness in the unused, unknown, unseen, and unusable parts of the places we inhabit. Architects create emptiness as much as space to be filled.

Writers, too, have a tendency to forget that not every vessel is made to be filled. My teaching partner, Ryan Drew, shared with me the word “skeuomorph” last night. Literally “a transformed vessel,” the word refers to the transformation of meaning that the vessel carries when it moves past its prime technological usage. Corinthian columns are rarely load-bearing anymore, and the chandelier in my dining room has electric lights in the shape of candle flames. Words can transform this way, too. “Digital” rarely refers to our fingers these days any more than the symbol for a phone has much connection to the dynamic computers we carry in our pockets and purses. Indeed, how often do we use our computers to compute?

The word also reminds me that ornamental vases are never made to do what functional vases are manufactured for. So, while the vessel does not carry flowers or flour, water or wine, it still carries meaning. In its wasted space, it carries beauty.

To be a potter is to shape empty spaces. Some of these empty spaces we fill and empty, again and again. And some remain in that realm of what we call a waste, a lack, negative space.

Our social imaginary—the way we collectively visualize our beliefs about what is real and possible—biases us toward usefulness. My Scottish-PEI cultural background demands usefulness. But the empty vase reminds us of St. Paul’s lesson about the artist and the clay:

“When a potter throws a vessel on his wheel, who is to say except the potter himself whether he forms the lump of clay into something glorious or humble?” (Romans 9:21, BUV*)

Even though I learned it a decade ago, I have forgotten this lesson. Like how the empty spots on my bookshelf magically fill with books, I unreflectively fill the wasted spaces of my day. In the fifteen-minute transition times, I slam off a few emails to save time later. I feel my ears with podcasts or audiobooks at every moment I’m away from a screen. I eat my breakfast while editing this draft. I am restless and always moving. The idea of jail terrifies me because there is nothing to do, nothing to read. Even to sleep, I must go through a series of mental exercises. Sleep has become hard work rather than meaningful, life-enriching, soul-filling wasted space.

It is no wonder that I find it hard to discover meaning. The ideas come more slowly, and the aha! moment is rare. Prayers rarely happen to me by accident. I never finish the poems I start on scraps of paper or in my journal. Reading is my everyday work, but it is also my delight and my vocation. I stare endlessly at the screen and then struggle to keep my eyes pinned to pages I yearn to read.

Though I am in the publication phase of a book on the cruciform—The Shape of the Cross in C.S. Lewis’s Spiritual Imagination—I have forgotten the other part of Oxford’s theological design: Wasted space is essential to intellectual, social, and spiritual transformation.

Matthew Arnold captured something with his description of Oxford’s “dreaming spires.” He reminds us to look up. And he is right that as makers, we humans are also fillers of the spaces we make.

However, in reclaiming the sacredness of wasted space, I am resisting his empire-building, fill-in-all-the-spaces vision of the world.

Most of all, though, I am choosing to leave room in my crowded mind for the unusual, the unexpected, the unnecessary, the unbidden, the intangible, the ignoble, the uncomfortable, the impossible, and the Other. I need room to breathe, to dream, to look up. I need once again to become an architect of wasted space in my life.

*BUV: Brenton’s Unauthorized Version

Note: A previous version of this piece put Sulva as the Mercury figure in the Ransom Cycle; truly, it is Viritrilbia, and I even made a handy “Planet Narnia Chart” so I wouldn’t forget. Ah well, it’s a very mercurial figure in all worlds.

What a disarming way to get behind my gatekeepers and shine a bold light in my soul – clutter! It’s the unfinished poems (and in my case, the languishing novel draft) that make me sit up and take notice. We’re murdering these unborn works of art by neglect.

The quality of your insights and your deft writing always speak deeply to me. Let’s make that space so the tunes we hum in it resonate with our fellows.

LikeLike

Hi Ruth, thank you for such a lovely and encouraging note. I actually dug out one of those unfinished poems last night; unsurprisingly, it was about a kind of imposter syndrome! And another begins, “Why does cold air seem like fresh air.” Fitting.

LikeLike

Thank you for this beautiful, inspiring reflection. I enjoyed it immensely. One small correction: the name of Dorothy Sayers’s novel is Gaudy Night, not Nights.

LikeLike

Hi Tim, thanks for the correction and the encouraging note. I ready Gaudy Night (note the singular) a couple of years ago for the first time.

LikeLike

And it’s the moon that’s Sulva – Mercury is Viritrilbia. But thanks, regardless. Perhaps take a look at Christopher Alexander’s “A Pattern Language” and “The Timeless Way of Building,” which have a lot to say about space in houses and cities, and when it feels human and when it doesn’t.

LikeLike

Thanks Catherine, I made the switch and added a self-deprecating note and a link to a resource. Christopher Alexander, cool. I keep meaning to read Kathleen Norris on her Spiritual Geography.

LikeLike

Brenton, this is truly beautiful writing – brought tears. Thank you for sharing it.

Do let us know where we can obtain the book when it is finally out.

Dana

LikeLike

Dana, as always, your words are life-giving.

LikeLike

Skeuomorph- can’t wait to use that word in scrabble. Unlikely to get so many letters.

Such a beautiful piece of work Brenton as we prepare for Shirley’s 65th birthday celebration in Scotland. I’ll be sure to ‘look up’ as we walk the streets of Edinburgh.

LikeLike

Look up! Don’t trip on the cobblestones. Thanks, Andrew, Happy Birthday, Shirley!

LikeLike

What a beautiful piece, Brenton. I am so glad that you are writing regularly again. So am I after a break around the time that I retired from my parish duties last year. I will be celebrating my 70th birthday later this month and it is clear that writing will play a major part in the shape of my life from now on.

On my last visit to Oxford I attended an evening celebration of the centenary of Christopher Tolkien at the Bodleian Library where I met up with Sørina Higgins who was in conversation with Michael Ward. I decided that they weren’t going to be particularly interested in talking about me although Sørina was kind enough to recognise my name so I decided to mention your name as I know that you know both of them and to mention that you had stayed with us on your way to give a lecture in Oxford and to have dinner with Michael Ward.

This feels a bit like a letter that is taking a ride on the back of a blog post. So one last point. And this is about your beautiful piece. You express with great care much of what I feel about liturgical worship. I have been engaged in it ever since I began my theological studies in 1985, so that is 40 years ago and I have led liturgical worship in many different spaces in that time. The whole thing has a way of penetrating the very fabric of my being, something that I recognised recently when I attended a eucharist for Candlemas on February 2nd in the chapel of an Anglican Benedictine community who live just a few miles from us. I simply felt that I was in heaven even though at the end of the service the fire alarms went off because of the smoke ascending from the snuffed out candles.

LikeLike