Introducing The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien

I have confessed before how much I value the letter collections of authors that intrigue me. Besides C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, I’ve spent time in correspondence collections by Dorothy L. Sayers, James Thurber, L.M. Montgomery, E.B. White, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Joy Davidman, and Warren Lewis. To get closer to his sense of self, artistry, and vocation, I undertook a lengthy “Statistical Look at C.S. Lewis’ Letter Writing” with some follow-up notes (see here).

On A Pilgrim in Narnia, I have written numerous reflections on Tolkien’s letters, including fan pieces, like “The Tolkien Letter that Every Lover of Middle-earth Must Read” (which we’ll come back to), and personal pieces, like his last letter to his daughter Priscilla. I’ve also reflected on my own life and work while reading Tolkien’s letters, such as “Battling a Mountain of Neglects with J.R.R. Tolkien.”

Humphrey Carpenter and Christopher Tolkien edited The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien in 1981. My copy is filled with folded-over pages and marginal notes. So you can imagine how excited I was when I heard that the 2023 restored edition would have 165 new bits of correspondence and some other expanded letters. I am grateful to the publishers, Baillie Tolkien (Christopher Tolkien’s Executor, Catherine McIlwaine (Tolkien Archivist at The Bodleian Libraries), Chris Smith (who wrote the new foreword), and Wayne G. Hammond & Christina Scull (who prepared the Index and provided some notes).

From Voyant to Spreadsheetophilia

Last week, I wrote about “Voyaging with Voyant in Tolkien’s Expanded Letters (Part 1: Background and Themes).” One of my realizations was how precious few letters are available to the general reader. In Tolkien’s most significant publication period—from The Hobbit in 1937 until his death in 1973—this new, greatly appreciated collection contains only 1 or 2 letters a month.

Part of my goal with last week’s piece was to experiment with the text analysis tools at Voyant https://voyant-tools.org/. What I found when going more deeply into Tolkien’s connections and relationships—the beginning of network analysis—was that I needed to step back and do more work on my own.

Frankly, my cleaning of the initial text was inadequate for this next layer of experimentation. I had previously excluded commentary and footnotes, but not greetings and addresses–leading to unhelpful biases.

Removing Doubles

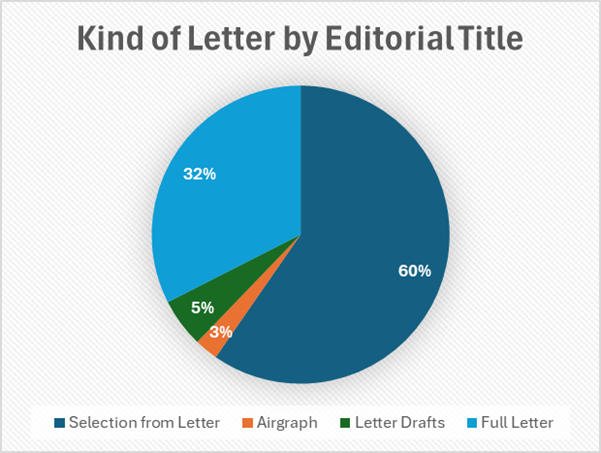

First, because so many letters were written with letterhead from Oxford, it skewed the word association tools like word clouds (and potential place analysis or GIS). Each of the 508 letter entries has an editorial title like this:

- “From a letter to…” 303 entries

- “From an airgraph to…” 13 entries

- “From a draft to…” 3 entries, as well as 23 other editorial mentions of a “draft” (two of which were marked “not sent”)

- “From a carbon of…” 1 entry

Leaving about 165 “To…” letters, i.e., full letters with greetings (e.g., “To Michael George”).

In my original cleaned digital text, about 1/3 of entries had potentially doubled data, so a letter title might say “To Stanley Unwin, Allen & Unwin,” and then Tolkien’s greeting: “Dear Sir Stanley” or “Dear Mr Unwin.” Thus, we have an unhelpful repetition of names.

There is also a lot of name doubling—not just Unwin, but multiple generations of Gordon, Michael, Christopher, Joan, Lewis, and so on. Cleaning the text helped me work these out.

New Letter Organization

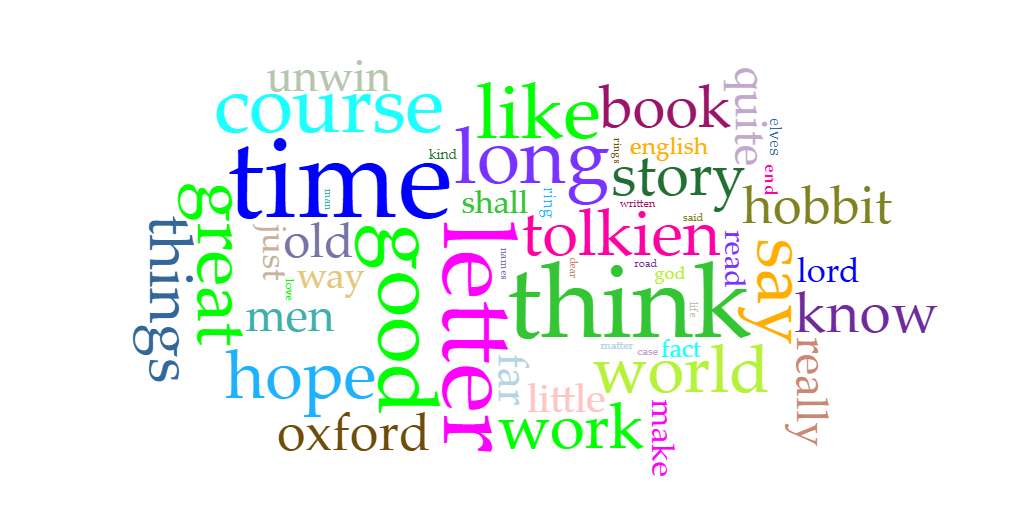

The visual analogies from Part 1 still work, like this one:

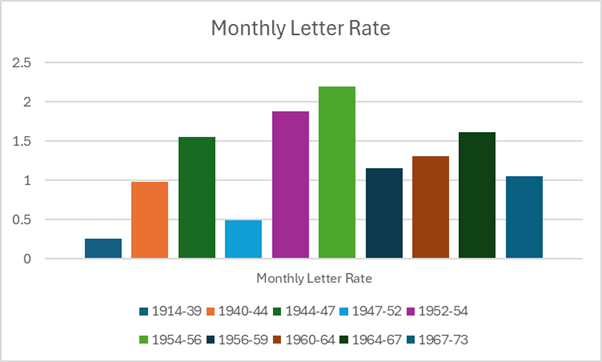

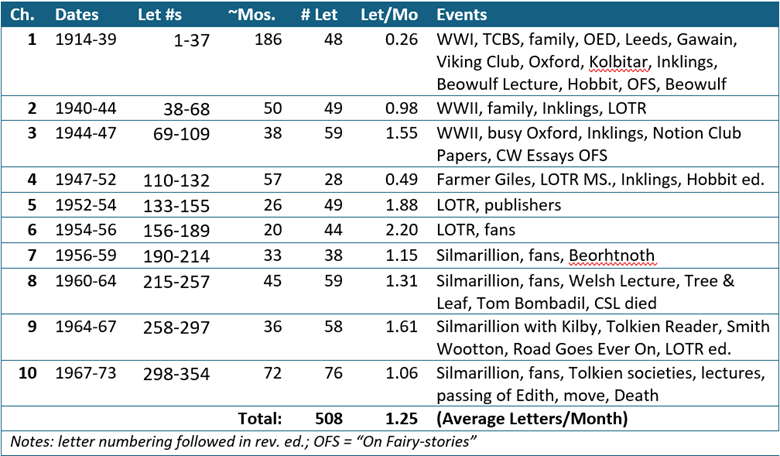

Dividing the text of the Letters into 10 equal parts (chapters) has the benefit of avoiding forced periods. However, when it comes to relationships, I am very interested in periods defined by their connections.

So, I decided to create a yearly breakdown of the letters. As the years 1916-1936 have very few extant letters, I ran averages for both the full volume (1916-73) and the period of 1937-73. Voyant or another platform might have a process to do this, but I did not find one. So, I spent a good part of a day remaking a Digital Text and creating some old-fashioned spreadsheets. And counting letters by hand.

Admittedly, the initial spreadsheet is a wee bit full:

In the columns on the left, we have the original 10-part chapter divisions and their time periods set next to the years that we have letters (scattered between 1916 and 1936 and then more consistent from 1937—the year The Hobbit was published—and his death in 1973).

This is a highly functional spreadsheet for me, though I cannot imagine other people finding it intuitive. If you think you could use it (and address errors), let me know.

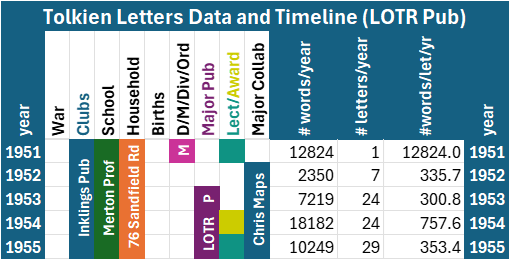

This trimmer chart on the right allows us to focus on the data more, but you need a strong sense of Tolkien’s timeline. I use the Tolkien Society timeline, which I nuanced in a conversation with DeepSeek AI (using the Letters, Carpenter’s Tolkien biography, and open-source materials as the data set).

I also understand there is a lot of colour. That works for me and allows me to add secondary categories.

With my newly organized doc and a hand count of the letters, I could count the number of words in each year, allowing us to see averages like the number of letters and words per year.

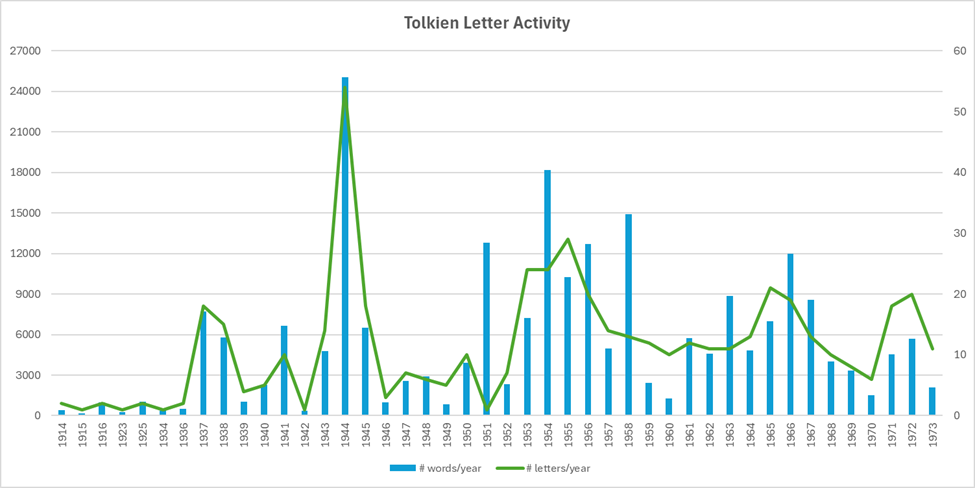

In the chart below, the green line shows the number of letters included in the collection from each year. There is an average of 11.5 letters each year—roughly one a month.

The averages on their own, though, don’t show the wild diversity of these figures, which you can see when the blue bar and green line go in opposite directions. In 1944, there were a lot of long letters to his sons in the war and a great number of letters, overall. In 1968, Tolkien was responding in detail to fans of The Lord of the Rings, so that there were fewer letters, but these were even longer.

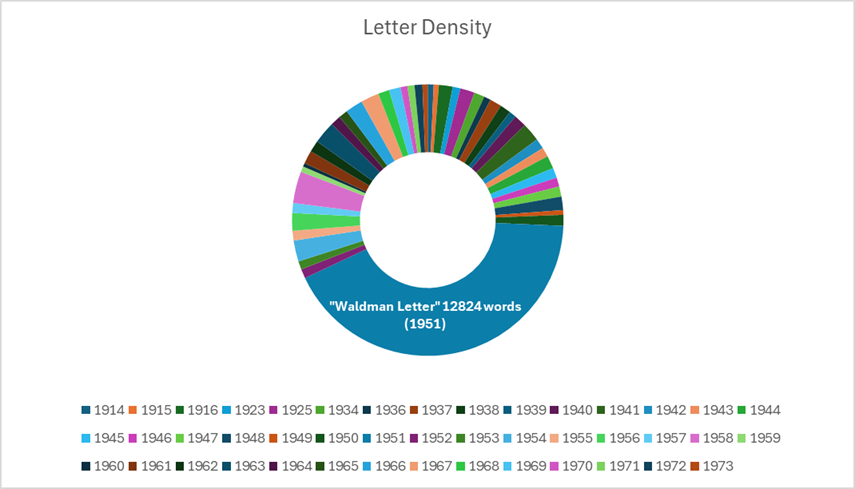

The piece that throws off the data totally is the “Milton Waldman Letter.” The Letters include only one piece of correspondence in 1951, a facsimile of a description of The Silmarillion that Tolkien sent Collins publisher Milton Waldman. This is “The Tolkien Letter that Every Lover of Middle-earth Must Read”—or so I claimed in a previous post.

It really is a remarkable letter—which is why Mr. Waldman made a copy … and kept it, even when Collins decided to pass on The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion. In time, editor Christopher Tolkien included it as a prolegomenon to The Silmarillion.

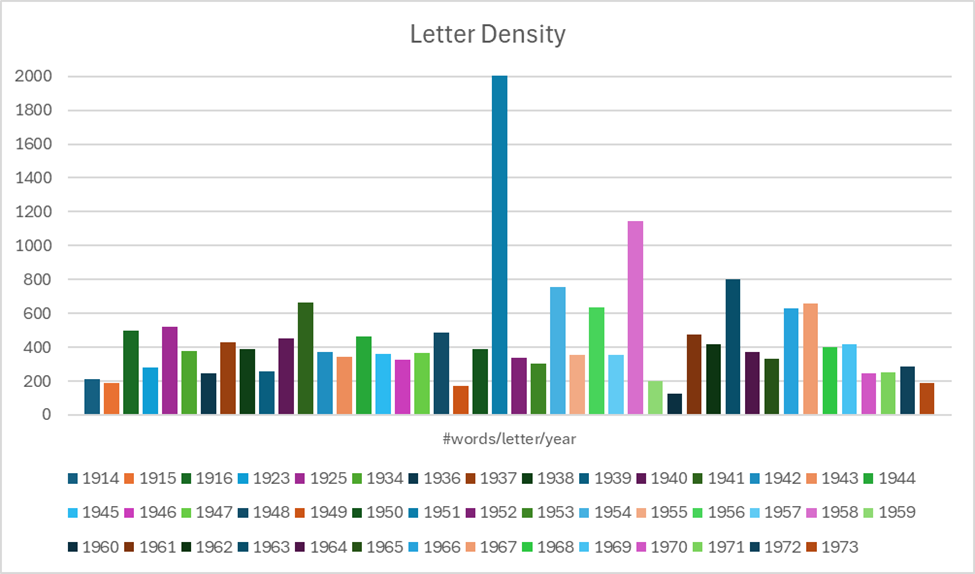

Statistically speaking, this letter throws off the data in wonderful ways. I capped the letter density chart at “2,000 words” above; actually, that blue column should extend about 6 times as high! Here’s another way of looking at it:

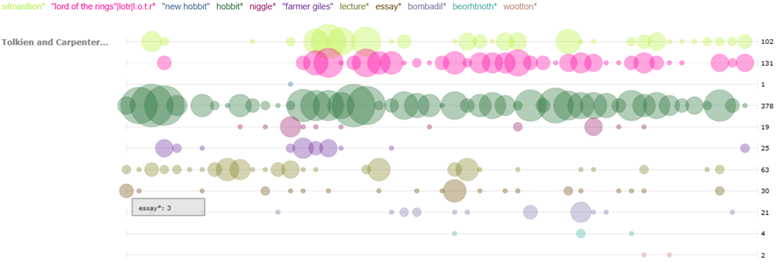

And then there are bubbles, with the Milton Waldman bubble way off the chart:

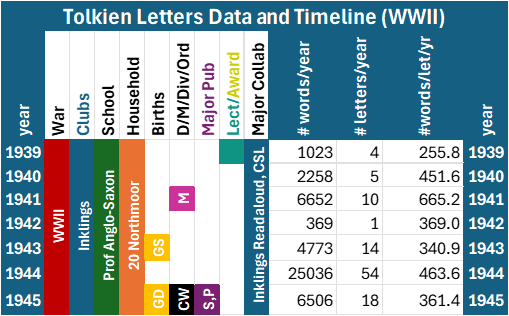

Ultimately, what this data reorganization has really done is give me a spreadsheet with which to draw some pictures. For example, here is my chart narrowed in on the years of WWII.

In the period where Tolkien is supporting his children in wartime and enjoying grandchildren, he is at a point of peek support from the Inklings. While we can guess at the inconveniences and fears of WWII, what the chart cannot show is how his Oxford workload increases—though the paucity of publications in this period is a hint.

1951-55 is an extremely stressful period for Tolkien. He has completed The Lord of the Rings—or, at least, he is ready to publish it. He has grown convinced that it must be published with The Silmarillion, though he has not yet produced a manuscript for his legendarium’s founding book. When his publishers, Allen & Unwin, balk at a contract involving The Silmarillion (which they have not seen), Tolkien pitches the project to Collins Publishing (this is where Milton Waldman comes in). Ultimately, Tolkien will fail with Collins and return with gratitude to Allen & Unwin. They rush to meet a 1954-54 series of deadlines, including glossaries, maps (drawn by Christopher), and endless copy editing.

What my chart brings home to me is the relative stability during those years. Edith and Ronald are settled in an empty nest home and there are very few family events in the period (one marriage). The grandchildren are growing and he has secured the professorship that will bring him to retirement at the end of the decade. While there is much personal difficulty in this period, it was less stressful in terms of raising children and sending them to war, or constantly preparing for the next job or house.

The spreadsheets help me close-read the letters and see history in new ways.

What the Letters Are and Are Not

In my next post, I will turn to look at some of Tolkien’s relationships as the data visualizes them. In the meantime, an obvious but essential observation.

As I’ve been rereading the letters, I am moved by how intensely personal and intimate Tolkien’s letters are to his children—especially to his sons in wartime, but also as they were children with childhood’s challenges. Seeing the data, I was struck by how intensely committed Tolkien was to writing and sharing his legendarium. There are more publishers than family members in the letters, and names from The Lord of the Rings are as common as people in his everyday life.

Now, a cynical reader may conclude that my use of Voyant to organize and visualize data from the digital text of the letters is circular: In a collection designed to shed light on Tolkien’s creative processes, it is not shocking that my data points to Tolkien’s creative processes.

However, it is essential to recognize that, by definition, letter collections are selective. Even in an exhaustive collection, the letters that survive are not necessarily the most important pieces of evidence.

Letters are also deeply contextual. In times of war, they are filled with codes and censorship. Letters among those we live with are rare. We don’t have a lot of letters between the Inklings because they met regularly in Oxford. Their shared words are written on the walls of pubs and cobblestone pathways in a kind of invisible ink that I do not have the technology to recover. By contrast, the father and son duo at Allen & Unwin publishers—and quite a number of their editors—lived elsewhere. Almost all of their communication happens by mail.

For all of these reasons, the evidence of epistolary history can never be judged by the weight of the remaining mailbags.

In the next post, I want to press in a bit more on Tolkien’s relationships.

I too love reading the correspondence of historic figures I respect. So much to learn, even in their casual asides. I was thrilled to purchase the expanded edition of Tolkien’s letters when I recently learned of their publication. (I think it was actually A Pilgrim in Narnia where I heard the news.)

This post is going to take some time to digest, being so detailed, but I wanted to thank you right away for standing in the first ranks of Inkling scholars researching these important subjects.

LikeLike

Thanks Rob!

LikeLike

Hi Rob, time to digest is what I need too! I pulled back to take another run at it.

LikeLike

Pingback: Tolkien Gleanings #286 « The Spyders of Burslem

I am very struck that the time that you describe as a particularly stressed one was also one of the most creative in Tolkien’s life. Obviously there is the publication of The Lord of the Rings and I think we all owe a debt of thanks to his publishers for refusing to publish The Silmarillion along with LOTR. I bet that JRR didn’t see it that way though. It helps me to get a better perspective on things to see that me getting my way is not necessarily the best way!

And the letter to Milton Waldman is perhaps one of the best examples there is of a piece of work that did not accomplish its stated intention and yet has born fruit many times over since that time. I go back to it frequently and always to good effect.

LikeLike

These are great observations, Stephen. One of those propitious problems, a eucatastrophe. Who knows when we would have gotten LOTR while Tolkien struggled to finish the Silmarillion?

LikeLike

I’ve moved to Substack.

https://open.substack.com/pub/annettekristynik?r=cmfg0&utm_medium=ios

LikeLike