Quite innocently, early the other morning, I woke up to a video in my Messenger inbox from Paul Ford. I am not someone who is terribly attracted to products like this, but Paul F. Ford is the author of an excellent Companion to Narnia. I don’t think I paid it much attention (beyond an appreciation for nice book design) until, after a request, Paul sent me his graduate thesis, which is particularly sensitive to C.S. Lewis’ spirituality. Knowing the care Paul showed in his research–and watching him consistently engage with intellectual generosity to Lewis fans online–I have been able to enjoy his Companion in new ways.

In any case, you may know what it’s like for someone to send you a reel without any explanation. As I have spent years shaping an “Internet of Awesome” in my algorithmic identity, I rarely get trolls or agenda pushers. A handful of my mentors and colleagues drop something to me once in a while–either funny or containing a point of connection in our thinking. We also have some family threads that end up with pretty random shorts and vids, but this randomness also results in some of my favourite new music.

This share from Paul, though, was totally new. I clicked on the video, and I immediately assumed it was a pretty well-done spoof. Honestly, in his bearded lumberjack shirt look, the guy is just too good-looking for real life! And who is “Sean of the South”?

Then … well, then I stopped and listened. I love libraries and librarians and books, and I trust Paul. So I kept listening. As it turns out, it wasn’t a parody or off-centre bit of comedy, but a heartfelt literary tribute to a particular librarian’s intervention in his young life. I don’t want to spoil the effect, but tears clouded my already early-morning bleary eyes.

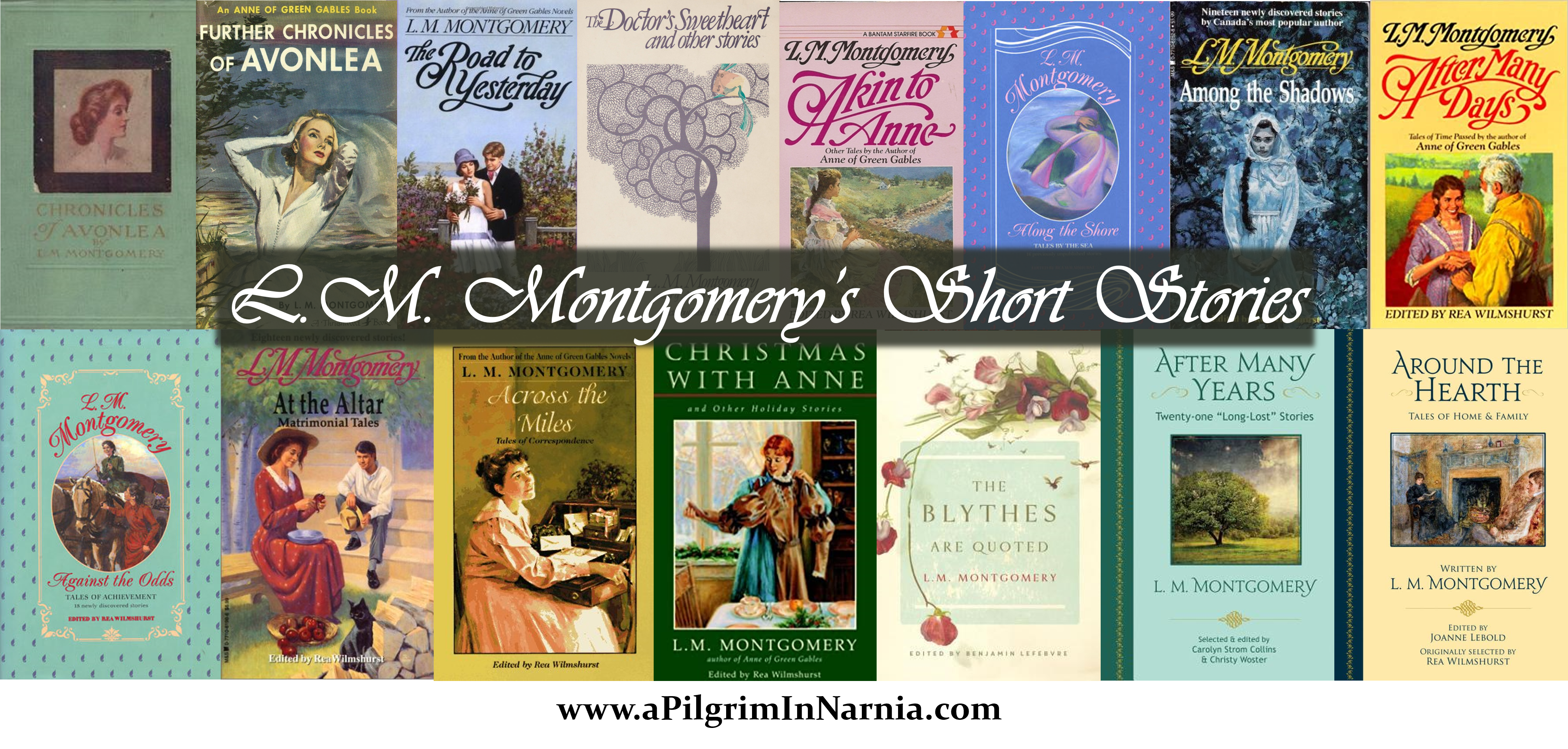

So why did Paul send this to me? As far as I know, we are not in some club dedicated to admiring philosopher lumberjacks from the south. But there is a moment in the story where the librarian slips an L.M. Montgomery book into Sean’s pile of Louis L’Amour (whom I have never read, but I am told he was moderately successful as a popular writer of guys’ fiction). “This looks like a Girl Book,” the teenage Sean responds to the librarian’s nudge. “Keep an open mind,” she responds. Sean did, and went back to the librarian, confessing that it was one of the best things he had ever read.

The story continues to what most will think is the best part, but what got to me was the word he used to describe Montgomery: Tenderness.

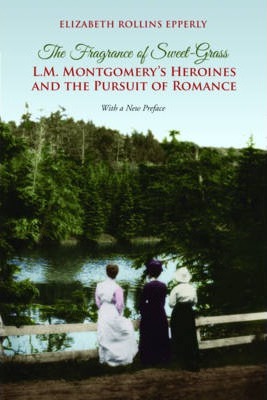

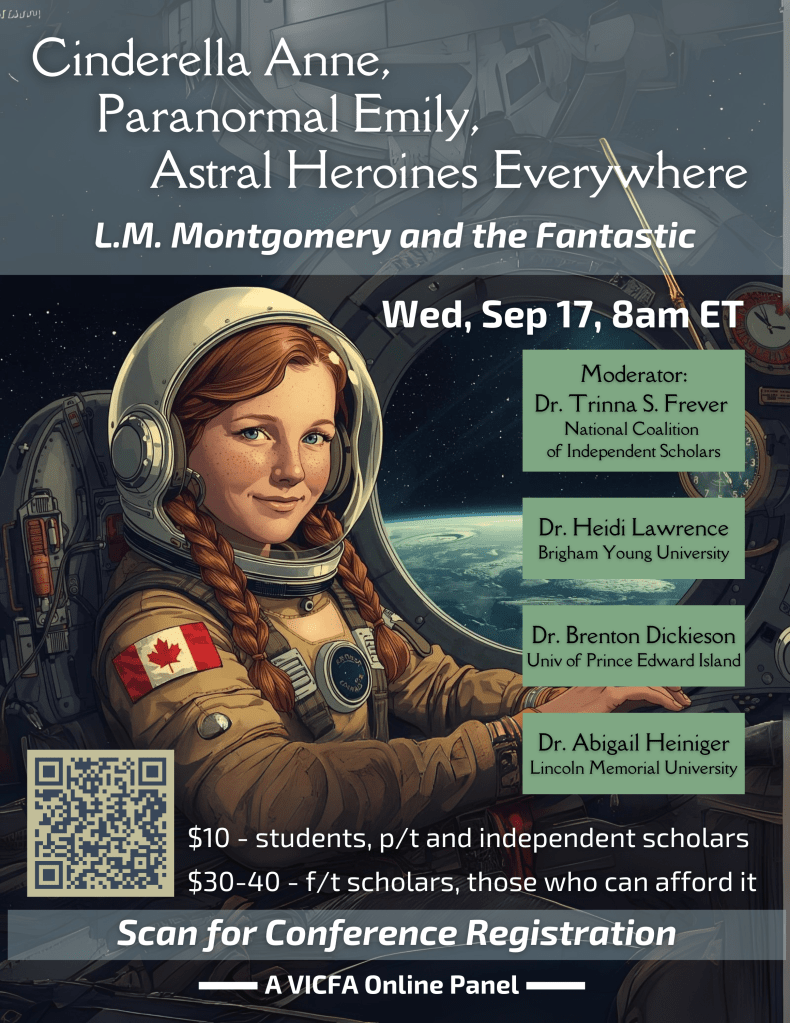

Ever since I first played the clip, that word has just been rolling around inside of me. Tenderness. When I think of Anne of Green Gables and Emily of New Moon, I think of the singular imaginative possibilities of these two heroines. When I think of her stories, I think of atmosphere and humour. I have always said that my initial attraction to Montgomery is because of my writerly and artistic vocation, which is true. But I think this serious and cerebral Sean of the South has it right: Tenderness.

The reason I have no idea who this sensitive and savvy Sean of the South is–a fairly popular columnist named Sean Dietrich–is not just because I am not American. It is true that I am deficient in my knowledge of American storytellers beyond speculative fiction. However, I suspect that if this stylish scribbler had popped up on my screen doing anything other than playing a banjo, I would have dismissed it. I fear that I have developed a kind of allergy to certain kinds of masculinity as presented in the media, and I would have skirted past this august author.

Now, I am a bearded gardener, and the son of a bearded farmer. My father and I lumberjacked together in plaid–though I was pre-beard at the time. My allergy has never been am aversion to the idea of masculine trades or manly appearances, but some collective sense of what it means to be a guy that I have never understood. My farming father was a man’s man, no doubt–a hockey player and homebrewer driving his tractor home in the setting sun kind of man. But he was always something else to me.

Though I doubt I have a full sense of this man who required a certain kind of violent ruggedness in his lifestyle, his masculinity to me was humour, storytelling, sensitive parenting, curiosity, strategy, and fierce loyalty. Though I always felt like an alien in my farming community, in my fishing-village school, in my hockey locker rooms and among the clusters of guys hanging out in school halls, it was not my father who made me feel so. He was often frustrated with my lack of common sense and attention to detail, but I never felt like he was threatened by my queer awkwardness any more than he was threatened by my mom’s powerful 1980s feminism.

In the end, my father’s physical strength was unable to save his family. As he disappeared into our burning home to rescue his youngest son, though, I never felt like he failed as a man. Whatever manliness is, I know, is found in that moment, a cruciform shadow in the doorway, taking a breath before laying it all down. That’s the idea of manness in my mind–not the one on magazine covers or in locker-room talk or in other spaces that communicate clearly, “Brenton, you don’t belong here.”

And so tenderness: My child-hand in his, my unsplit skin against his hands made rough by earth and fire and wood. For all the reasons I read Girl Books, I think tenderness is an unrecognized quality I have been searching for. I have thought of sensitivity–which is why I read Narnia, Montgomery, Jane Austen, and books that no other guys I knew growing up were reading. But there may be something more, too.

I know I am unusual, and I embrace that, but I want to think more about tenderness–and I see that characteristic in Paul Ford’s scholarship–and not a few of the essayists and scholars I give my time to.

In amy vase, it’s a sweet video, and I hope you enjoy it–and find a characteristic in reading that goes beyond our often limited imaginations of boys and girls and the books they write and read.

Note, this song came on when I was writing this, The Tragically Hip’s “The Luxury” came on, with quite a strikingly opposite of manliness and tenderness than I’ve been talking about here: