Imaginary worlds are common trade now. Our world is linked to others through secret passages or magic portholes or, in the case of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials (the Golden Compass) the worlds are bridged by intricate  tears in the fabrics of space and time. While these worlds may always have existed, I think that Narnia is a template for all that came after. The Magic Wardrobe—along with rings and lampposts and mythical train rides—has sparked the speculative imaginations of many authors, including Philip Pullman and J.K. Rowling. Before Lewis, like in the fantasies of George MacDonald, fantastical creatures played in our own world; now, worlds apart are bridged by magical items or secret knowledge.

tears in the fabrics of space and time. While these worlds may always have existed, I think that Narnia is a template for all that came after. The Magic Wardrobe—along with rings and lampposts and mythical train rides—has sparked the speculative imaginations of many authors, including Philip Pullman and J.K. Rowling. Before Lewis, like in the fantasies of George MacDonald, fantastical creatures played in our own world; now, worlds apart are bridged by magical items or secret knowledge.

In Bridge to Terabithia, Katherine Paterson tries to capture the realm of  fantasy that lives very near our own. Terabithia is a mythical world where human children rule an animated population of giants and faeries and animals that reveal their alliances. Terabithia is linked to the real world—in this case, rural Maryland, on the edge of suburban Washington, D.C.—by a rope tied above a small creek.

fantasy that lives very near our own. Terabithia is a mythical world where human children rule an animated population of giants and faeries and animals that reveal their alliances. Terabithia is linked to the real world—in this case, rural Maryland, on the edge of suburban Washington, D.C.—by a rope tied above a small creek.

The story centers around Jess, a fifth-grade artist stuck in a family that borders on rural white trash desperation. His dreams of being the fastest fifth-grader in the school are dashed when a new girl, Leslie, comes to town. The tomboyish child of hippies—we call them Rubber Booters here in Prince Edward Island; city folk finding rural beauty again in the late 1970s—Leslie easily out-paces all the boys. Initially an enemy, Leslie’s active imagination soon wins over Jess, who adds pictures to Leslie’s narrative fantasies. Together, they discover Terabithia, renovating it, and launching their battles from the safety of their treehouse fortress.

Bridge to Terabithia is a unique book in that Terabithia is a speculative world entirely invented by the main characters. Leslie dreams it up as their friendship is at its very beginnings:

“Do you know what we need?” Leslie called to him. Intoxicated as he was with the heavens, he couldn’t imagine needing anything on earth.

“We need a place,” she said. “just for us. It would be so secret that we would never tell anyone in the whole world about it. Jess came swinging back and dragged his feet to stop. She lowered her voice almost to a whisper. “It might be a whole secret country,” she continued, “and you and I would be the rulers of it … it could be a magic country like Narnia, and the only way you can get in is by swinging across on this enchanted rope.” Her eyes were bright. She grabbed the rope. “Come on,” she said. “Let’s find a place to build our castle stronghold” (38-39).

In most books, children stumble upon the fantastical world; here, the children create it and then inhabit it. In this sense, I think Paterson really captures something important about childhood imaginations and the power they hold over the imaginers. If every Narnia is a world of wonder, it is only in Terabithia where the children are the true rulers, where they define the boundaries of  their “castle strongholds.”

their “castle strongholds.”

Of course, these strongholds could be literal or metaphorical. The novel is really about death and life: the struggle against the death of imagination, the dying of friendship and family, and the last breath of a dying culture. It is also about real death, the death of a friend, as experienced by ten-year-olds. In the end, Terabithia threatens the very life of its rulers. I wonder what the impact of this reality is. Did Paterson mean to suggest that imagination kills us? Is the struggle for art and the creative and the fantastical really a dead-end? To me, these questions are unanswered.

Although Paterson does an important thing in capturing the speculative  imagination of preteens, in this way I think Terabithia falls far short of Narnia. The beauty of Narnia—the series, that is—is that it excites and challenges and ignites the imagination. In C.S. Lewis and Madeleine L’Engle and George MacDonald, the imaginary world shows us the very real—the more Real than the real, even. But with Paterson, it is the material that ultimately dominates: the stuff we touch and taste and smell are more substantial that the worlds inside our heart that are struggling to get out.

imagination of preteens, in this way I think Terabithia falls far short of Narnia. The beauty of Narnia—the series, that is—is that it excites and challenges and ignites the imagination. In C.S. Lewis and Madeleine L’Engle and George MacDonald, the imaginary world shows us the very real—the more Real than the real, even. But with Paterson, it is the material that ultimately dominates: the stuff we touch and taste and smell are more substantial that the worlds inside our heart that are struggling to get out.

And although the novel captures a child’s imagination—and she does this superbly with Jess in the final two chapters—her Terabithia is lacking. With Narnia (and L’Engle’s tilted planets and Pullman’s parallel universes) we are given just enough detail to imagine the rich, beautiful, sometimes even frightening worlds. Paterson intended something similar with Terabithia—the influence of Lewis is named and obvious throughout—but I think that she did not completely succeed in giving us a landscape to imagine Terabithia in its richness.

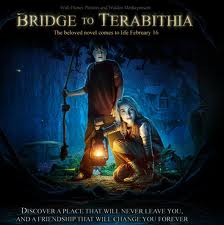

In this way, I think the 2007 film really supplies the imaginative breadth of what Terabithia could be like in the novel. Both the main characters—Jess  played by Josh Hutcherson and Leslie played by AnnaSophia Robb—captured the depth of characters we see in the novel, particularly the energy, awkwardness, and creative intelligence of these preteens. Paterson’s son, David, draws on the strength of the novel in the screenplay, allowing the characters’ personalities to grow. But it was really the effect-work and photography that was its genius. The set of Terabithia was a simple American forest with a ten-year-old makeshift treehouse, but its magic was brilliantly captured by weaving in hand-drawn creatures and tickle trunk costumes. In the film, Terabithia really felt like a child’s imagination to me.

played by Josh Hutcherson and Leslie played by AnnaSophia Robb—captured the depth of characters we see in the novel, particularly the energy, awkwardness, and creative intelligence of these preteens. Paterson’s son, David, draws on the strength of the novel in the screenplay, allowing the characters’ personalities to grow. But it was really the effect-work and photography that was its genius. The set of Terabithia was a simple American forest with a ten-year-old makeshift treehouse, but its magic was brilliantly captured by weaving in hand-drawn creatures and tickle trunk costumes. In the film, Terabithia really felt like a child’s imagination to me.

This is one of the rare cases where I think the film is better than the book at exploring Narnian worlds. When it is time talk about the death of a friend, the novel is irreplaceable. But if we are setting imaginations free, the movie is far truer to what Paterson’s literary mentors were on about.

You have a typo at the end: “film is better than the movie,” when I do believe you mean the book. +)

You have an interesting discussion of an excellent book and an excellent movie. Yet I would put forth that I don’t think Paterson was trying to write a Narnian story at all. It’s not a fantasy novel, but work dealing solidly with the real world and its issues. The characters of Jess and Leslie love Narnia and are inspired by that sort of magical world, but I think the book itself is more about people who love Narnia that it is trying to explore Narnian-style worlds. Terabithia isn’t more developed and immersive because we, the readers, cannot directly enter Jess and Leslie’s minds and see exactly what they are seeing. But we can see their reactions, and how they use Terabithia to deal with their real world. So while the book doesn’t work on the fantasy level like Narnia does, I don’t believe it was intended to. On its chosen level, it works tremendously powerfully.

I was very impressed with the movie, although I do think it spent a teensy bit too much time in CGI action scenes with its creatures to appeal to the short-attentioned Disney-channel crowd, however amusingly designed they were. The songs could have used some work, too. But ultimately those are little nitpicks. The casting is excellent, and the overall mood of the movie captures well the book’s gentle nostalgia, joy, and strength in dealing with grief. It moved me much like the book did — it was all I could do to not cry through the end, and I don’t consider myself particularly emotional. The intelligence and maturity with which it approaches its story is commendable, and all too rare in modern movie-making. It’s one of the few movies I am really glad I own, even if I don’t watch it often.

LikeLike

Thanks on the typo.

You were right: I do think the movie does things the book doesn’t (or cannot) do. I was moved by the movie, but felt that pain of loss in book as well. I’m a bit of a sucker for that sad ending film, so that might not be saying much.

I think I did make a genre mistake–or at least a misstep–in comparing Narnia with Terabithia. There is obvious influence: it is hard to imagine that a Terabithia is not connected to the Narnian Terebinthia, particularly as it is an island with a haunting death curse of sorts. I may not gush enough at this book; however, I think I do give credit where credit is due:

I think Bridge to Terabithia does what it intends to do, though I admit I’m not sure what she is saying about the death of imagination (or I’m afraid of what she is saying, in a sense).

Would love if you wanted to re-write your critique of my review as a guest blog, if you are interested. I’m at junkola[at]gmail[dot].com

LikeLike

Pingback: “Jill Pole Was Crying Behind the Gym”: Bullying at the Experiment House | A Pilgrim in Narnia

I just bought this book today!

LikeLike

Would love to hear your thoughts!

LikeLike

Katherine Paterson is an extraordinary writer…her story is actually based on some real life events…no, she was not imitating Narnia or any other world other than the imagination of real children…. and the book is on life and death… a real death of a friend of someone quite close to her. Note that her son was part of the filmmaking process. While of course the book is better, the film was wonderful as the person who inspired the book was a very large part of that.

LikeLike

oh, and as far as imagination…. children do eventually grow out of their imaginatiion…well, most do. Except for writers like Paterson 😉

LikeLike

I didn’t know that she was basing the story on anything in particular except the universal story of loss and love. I hope, personally, that my imagination doesn’t go away. However, I do forget to play sometimes.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Difference Between Pressure & Discipline: My Reflection on my 100th Post | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Wormwood Reborn? A Screwtapian Look at The Gates by John Connolly (Hell Series Part 1) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: A Shore-side View of the Pilgrimage: My 2nd Anniversary Reflection | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Meeting Prue: Reflections on Wildwood by Colin Meloy and Carson Ellis | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: A Quick Detour: On Choosing University Readings | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: 2014: A Year of Reading | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: On Embracing my Inner Nerd, Or Erasing the Division between Head and Heart | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Announcement: Mythologies of Love and Sex (Signum University Class) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: 2016: A Year of Reading | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Fun With Stats 1: Lessons on Growth from 5 Years of Blogging | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: The Mythogenic Principle, Or Why Reading Zombie Lit at the Beach is a Very Bad Idea | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Wormwood Reborn? A Screwtapian Look at The Gates by John Connolly (A Little Hallowe’en Demonic Lit) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: On Embracing my Inner Nerd, Or Erasing the Division between Head and Heart (Throwback Thursday) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Masters Class Announcement: C.S. Lewis and Mythologies of Love and Sex (Signum University Class) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: C.S. Lewis, Gender, and The Four Loves: An Open Class (Tues, Sep 17, 7pm Eastern) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: 5 Ways to Find Open Source Academic Research on C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and the Inklings | A Pilgrim in Narnia