Ere long and ever ago when this blog was young, I wrote about the “Worst Book Description Ever” from C.S. Lewis’ science fiction classic, Out of the Silent Planet. As is sometimes so in the burdens of experience, I have since read worse book descriptions–not just of Out of the Silent Planet, but also of many, many books that it is clear the cover designers have never read.

Ere long and ever ago when this blog was young, I wrote about the “Worst Book Description Ever” from C.S. Lewis’ science fiction classic, Out of the Silent Planet. As is sometimes so in the burdens of experience, I have since read worse book descriptions–not just of Out of the Silent Planet, but also of many, many books that it is clear the cover designers have never read.  I did note in that decade-old post that I liked some of the cover art of the aptly misnamed “Space Trilogy.” The Pan series at the top of the page is clearly informed by the stories of the novels in fairly sophisticated symbolic ways. They also have a kind of demonic atmosphere that connects the three books and reveals its connections to The Screwtape Letters and the incomplete “Dark Tower” story–what I call the Ransom Cycle.

I did note in that decade-old post that I liked some of the cover art of the aptly misnamed “Space Trilogy.” The Pan series at the top of the page is clearly informed by the stories of the novels in fairly sophisticated symbolic ways. They also have a kind of demonic atmosphere that connects the three books and reveals its connections to The Screwtape Letters and the incomplete “Dark Tower” story–what I call the Ransom Cycle.

Perelandra poses some neat challenges for cover art design. The whole planet is so tinged with green light and vibrant colour that a cover design might come off as lurid, or even garish. Just above, the blue island cover captures the “fixed land” aspect of the story with an intriguing dragon-like or serpentine hint in the island’s design. It’s well done–even if the colouring is a bit off. The middle fish-riding scene above is also off in colour, but evocative of the adventure. And the remake of an older Sci Fi design above on the right does not quite capture the elements in the way I imagine the novel, but gets the feeling right for me.

Perelandra poses some neat challenges for cover art design. The whole planet is so tinged with green light and vibrant colour that a cover design might come off as lurid, or even garish. Just above, the blue island cover captures the “fixed land” aspect of the story with an intriguing dragon-like or serpentine hint in the island’s design. It’s well done–even if the colouring is a bit off. The middle fish-riding scene above is also off in colour, but evocative of the adventure. And the remake of an older Sci Fi design above on the right does not quite capture the elements in the way I imagine the novel, but gets the feeling right for me.

Other cover designers, though, fail to get the essence of this strange space fantasy when trying to capture the symbolic or atmospheric features.

The tubular natural cover above is fine, but kind of ridiculous. The brown-green pair of Voyage to Venus US editions both work in elements of the novel–the greenness of skin, the god and goddess pairs Ransom will meet, travel in a coffin, a hint of the demonic–and manage to completely miss any feel for the novel itself. They did try to capture symbolism–as did the designer of the green apple cover of temptation and twin vision in the centre. This cover really does nothing, but does not have the deep sexist misreading of the temptation novel cover on the right. There are multiple terrible elements, but the nail polish shows they have completely misunderstood a novel deeply invested in gender symbolism and temptation. It is hard to imagine anyone doing worse.

Until you see other people try.

These three covers are clearly made by staff designers who haven’t read the book–though I have a certain kind of love for the one on the right, which is quite a beautiful cover for a novel I have never read.

One of the most difficult elements of the novel is capturing nudity among most of the main characters–Dr. Ransom, Tinidril, and Tor–when in a completely natural environment so different than our Terran one. Having two space angels trying to take form in the denouement of the novel doesn’t make things easier. Attempts to capture nudity on book covers don’t always go perfectly, as we can see here.

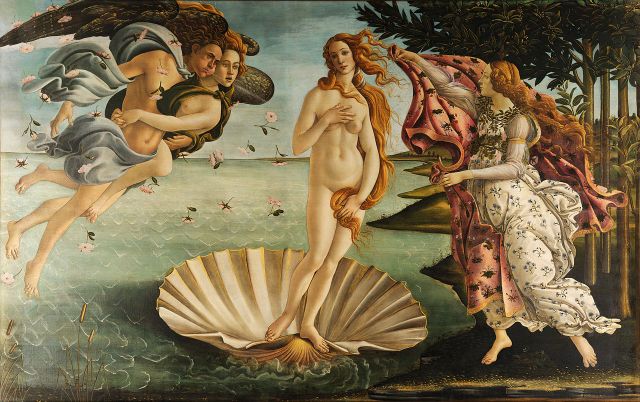

On the left, we have the hippie nudist couple covered delicately by a choreographed sequence of alien birds in flight while Tor gives a “hi guys!” shout from the distance. The middle picture is intriguing in a lot of ways, not least for evoking classical art on Venus (see below) and lovely fantasy elements informed by the book. However, Tinidril’s come hither figure and fashionable blue hair seem the opposite of her disturbing eyes and closed hands–unless she is about to pull back her hair for a full view of her Eve-like, belly button-less torso. I credit the picture on the right for attempting to use dance and symbolic painting to capture nudity in the novel, as well as Ransom’s encounter with the Lord and Lady of Perelandra. However, with the fighter jet, random poses, and demonic figure with horns, the whole cover looks more like an interpretation of Nena’s “99 Luftballons” by whomever it is that made Kate Bush’s videos.

On the left, we have the hippie nudist couple covered delicately by a choreographed sequence of alien birds in flight while Tor gives a “hi guys!” shout from the distance. The middle picture is intriguing in a lot of ways, not least for evoking classical art on Venus (see below) and lovely fantasy elements informed by the book. However, Tinidril’s come hither figure and fashionable blue hair seem the opposite of her disturbing eyes and closed hands–unless she is about to pull back her hair for a full view of her Eve-like, belly button-less torso. I credit the picture on the right for attempting to use dance and symbolic painting to capture nudity in the novel, as well as Ransom’s encounter with the Lord and Lady of Perelandra. However, with the fighter jet, random poses, and demonic figure with horns, the whole cover looks more like an interpretation of Nena’s “99 Luftballons” by whomever it is that made Kate Bush’s videos.

Nudity in popular, symbolically rich art is hard.

Thus, I am appreciative of this bit of fan art I found years ago (and would love to know who made it, if you happen to know). Ransom as the nude, piebald diplomat meeting his dog-like dragon is captured well in fantasy art that is meant to drift away from the realistic.

However, to capture the meeting of Ransom and Tinidril is more challenging because it has a kind of regal austerity. Perelandra’s Adam and Eve are green and naked, innocent and lordly, beautiful and yet not sexually alluring, farmers who frolic with their flock, and yet gods who are deeply implicated with their natural world. It was probably wise that, when they produced an opera of Perelandra, they used “The Birth of Venus” by Sandro Botticelli (late 15th c.) for their main image.

This Venus as Tinidril or as the planet Perelandra can work for those of us who know the novel.

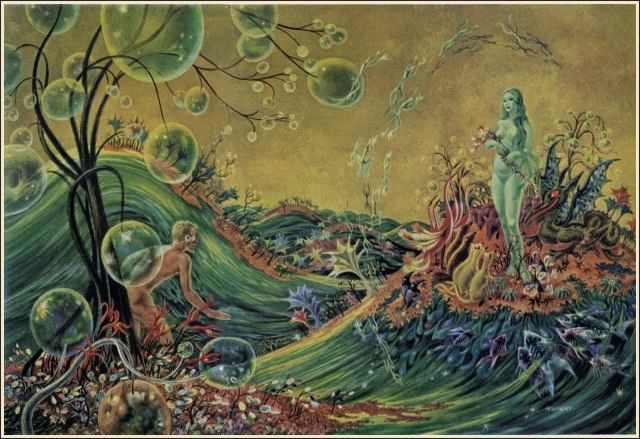

While not all attempts to capture Perelandra have been successful, I have applauded James Lewicki’s attempt in the first edition of Horizon journal (May 1959)–an illustration to an article by Edmund Fuller called, “The Christian Spaceman: C.S. Lewis.”

It is very much a piece of the period, but you can tell that Lewicki had actually taken the time to read Perelandra. Ransom is the Piebald Man, tanned on one side by his space voyage. He is naked and disoriented, caught on a floating island away from the only human he has yet seen. Lewicki has made an attempt to capture some of the vegetation, including the bubble trees–a “fruit” that provides refreshment and strength to Ransom in his visit to Venus. And there is the lady, a bit indistinct in the distance, but unashamed as she gathers flowers in her great, global garden. Though Lewicki is caught a tad awkwardly between Boticelli and fantasy art, I like the piece overall.

It is very much a piece of the period, but you can tell that Lewicki had actually taken the time to read Perelandra. Ransom is the Piebald Man, tanned on one side by his space voyage. He is naked and disoriented, caught on a floating island away from the only human he has yet seen. Lewicki has made an attempt to capture some of the vegetation, including the bubble trees–a “fruit” that provides refreshment and strength to Ransom in his visit to Venus. And there is the lady, a bit indistinct in the distance, but unashamed as she gathers flowers in her great, global garden. Though Lewicki is caught a tad awkwardly between Boticelli and fantasy art, I like the piece overall.

If you still feel a little bit unsatisfied by the painting, you should know that Lewis predicted you would be.

She was standing a few yards away, motionless but not apparently disengaged—doing something with her mind, perhaps even with her muscles, that he did not understand. It was the first time he had looked steadily at her, himself unobserved, and she seemed more strange to him than before. There was no category in the terrestrial mind which would fit her. Opposites met in her and were fused in a fashion for which we have no images. One way of putting it would be to say that neither our sacred nor our profane art could make her portrait. Beautiful, naked, shameless, young—she was obviously a goddess: but then the face, the face so calm that it escaped insipidity by the very concentration of its mildness, the face that was like the sudden coldness and stillness of a church when we enter it from a hot street—that made her a Madonna. The alert, inner silence which looked out from those eyes overawed him; yet at any moment she might laugh like a child, or run like Artemis or dance like a Maenad. All this against the golden sky which looked as if it were only an arm’s length above her head (Perelandra ch. 5).

We see how it was, visually speaking, an impossible task. So we should be grateful to James Lewicki for attempting to do moderately well on what so many have done so badly. Someone has recoloured and focussed the pieces, which I think enhances what we see–even if the colours are a bit brash (see the tiles below).

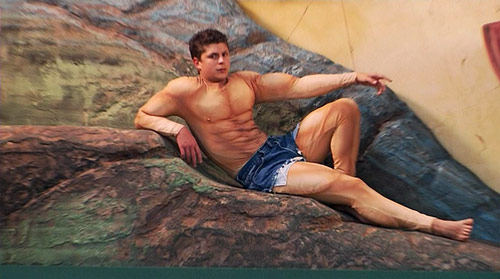

Of the imaginative fantasy art and terrible science-fiction interpretations, there is one cover of Perelandra that is clearly my favourite–one that I have tucked into every post that I felt I could get away with. This Avon cover on the right is just so painfully bad that it fills my Perelandra lectures with opportunities for pure mockery and teachable moments about art, writing, and culture.

Giant green-bodied/pale-faced naked alien gods looming above with wispy clouds right where their fancy bits might go, while a Never Nude Ransom stands defiantly against them in his superman pose.

Really, super tight jean shorts?

If the man and woman were the Adam and Eve of Perelandra, it makes sense that Tinidril has a friendly smile to welcome a dear friend. But look at her face: Does she look more like the innocent child-mother of a fresh new world, or the girl in high school who wouldn’t talk to you? And why is Tor holding a sphere and looking like a soap opera star trying to find his lines in the meaningful distance?

While parts that might offend censors have been tastefully covered for us readers, imagine the view from Ransom’s angle. Let’s face it: this god and goddess are extremely … fit and very … photogenic.

True, Ransom is looking pretty fine as well–not like someone who is slowly healing from near-fatal wounds and days of danger, distress, and darkness. Isn’t it amazing how Ransom’s hair is so neat and trimmed after months without a cut?

True, Ransom is looking pretty fine as well–not like someone who is slowly healing from near-fatal wounds and days of danger, distress, and darkness. Isn’t it amazing how Ransom’s hair is so neat and trimmed after months without a cut?

Of course, this picture is not of Tor and Tinidril, though, but of Malacandra and Perelandra, Mars and Venus, the angelic planetary intelligences Ransom knows as Eldils but who do not typically take visual form. At the end of Ransom’s adventures, they want to present themselves visually as they meet Tor and Tinidril, who have passed the test of temptation. After Mars and Venus attempt Ezekiel-like forms that disorient Ransom–though it would be amazing to see them in art–Ransom encounters them in a somewhat humanlike form. The passage is several pages, and I have included a part of that below, but here are some of the characteristics:

Their bodies, he said, were white. But a flush of diverse colours began at about the shoulders and streamed up the necks and flickered over face and head and stood out around the head like plumage or a halo…. The ‘plumage’ or halo of the one eldil was extremely different from that of the other. The Oyarsa of Mars shone with cold and morning colours, a little metallic—pure, hard, and bracing. The Oyarsa of Venus glowed with a warm splendour, full of the suggestion of teeming vegetable life.

The faces surprised him very much. Nothing less like the ‘angel’ of popular art could well be imagined. The rich variety, the hint of undeveloped possibilities, which make the interest of human faces, were entirely absent. He concluded in the end that [their look] was charity. But it was terrifyingly different from the expression of human charity, which we always see either blossoming out of, or hastening to descend into, natural affection. Here there was no affection at all: no least lingering memory of it even at ten million years’ distance, no germ from which it could spring in any future, however remote. Pure, spiritual, intellectual love shot from their faces like barbed lightning. It was so unlike the love we experience that its expression could easily be mistaken for ferocity.

Both the bodies were naked, and both were free from any sexual characteristics, either primary or secondary…. Ransom … has said that Malacandra was like rhythm and Perelandra like melody. He has said that Malacandra affected him like a quantitative, Perelandra like an accentual, metre. He thinks that the first held in his hand something like a spear, but the hands of the other were open, with the palms towards him…. At all events what Ransom saw at that moment was the real meaning of gender.

The two white creatures were sexless. But he of Malacandra was masculine (not male); she of Perelandra was feminine (not female). Malacandra seemed to him to have the look of one standing armed, at the ramparts of his own remote archaic world, in ceaseless vigilance, his eyes ever roaming the earthward horizon whence his danger came long ago…. But the eyes of Perelandra opened, as it were, inward, as if they were the curtained gateway to a world of waves and murmurings and wandering airs, of life that rocked in winds and splashed on mossy stones and descended as the dew and arose sunward in thin-spun delicacy of mist.

Well, that explains the spear and the open hands–and perhaps the looks of Mars and Venus are attempts to capture that here. And there is “mist” in this scene–hence the clouds? But I believe that I detect both primary and secondary sexual characteristics–and in very fine form. When pressed to paint a scene of sexless gendered gods, the artist chose to over-sex them.

Well, that explains the spear and the open hands–and perhaps the looks of Mars and Venus are attempts to capture that here. And there is “mist” in this scene–hence the clouds? But I believe that I detect both primary and secondary sexual characteristics–and in very fine form. When pressed to paint a scene of sexless gendered gods, the artist chose to over-sex them.

As Lewis is doing something with words that is too specific and complex for either words or images, I wouldn’t be so harsh to judge the artist except for three things.

As Lewis is doing something with words that is too specific and complex for either words or images, I wouldn’t be so harsh to judge the artist except for three things.

The first is the ridiculously sexy nature of the painting. I mean, goodness.

The second is the awkward racism of this piece. When confused by the colours–the text has the angels as white-bodied to the shoulder (white, not pinkish pale bland flesh like mine) with polyvalent heads or headpieces–the artist made the bodies a humanoid Perelandran green like Tor and Tinidril. But then the artist made the faces white–the pinkish pale bland flesh kind like mine, though better looking–to ensure that readers are selecting a book about tastefully sexy nude Caucasian aliens.

And third, I am sure that Dr. Ransom’s bum would have been quite well-shaped, given this artist’s visual imagination. So why the blue jean shorts?

And third, I am sure that Dr. Ransom’s bum would have been quite well-shaped, given this artist’s visual imagination. So why the blue jean shorts?

We are so far into the realm of the ridiculous that I am now going to explain why I call this the “Never Nude” book cover in my lectures and blog posts.

Besides “Never Nude” being an apt title for a book about nudity that an artist hilariously tries to hide with denim and wispy clouds, “Never Nude” is a pop culture thing.

For those who know the smart-goofy American TV serial, Arrested Development, you got it from the title. For the rest, “Never Nude” is a psychological complex that Tobias Fünke suffers from. Tobias, a former psychiatrist, is completely unable to be naked–even in the shower or with his wife. Instead, Tobias copes with Never Nude Syndrome by taking a cue from Dr. Ransom on Perelandra and wearing tight jean cutoffs under his clothes. While this syndrome is not widely known by psychologists, Tobias is not the only character to suffer from it.

For those who know the smart-goofy American TV serial, Arrested Development, you got it from the title. For the rest, “Never Nude” is a psychological complex that Tobias Fünke suffers from. Tobias, a former psychiatrist, is completely unable to be naked–even in the shower or with his wife. Instead, Tobias copes with Never Nude Syndrome by taking a cue from Dr. Ransom on Perelandra and wearing tight jean cutoffs under his clothes. While this syndrome is not widely known by psychologists, Tobias is not the only character to suffer from it.

And so I leave you with the final bit of nonsense in this mostly nonsense post about some good but mostly puzzling, lazy, irrelevant, racist, sexist, and infelicitous interpretations of SF writing on classic book covers. In this selection of Arrested Development clips, Tobias shares his Never Nude disability with others for the first time–a secret known only to his wife, Lindsay Bluth-Fünke, played by Portia de Rossi. In the clip, George Michael Bluth is wearing a nude suit beneath his clothes–initially to get used to playing a nude Adam in a live local rendition of Michelangelo’s “The Creation of Adam.” As the suit makes him look more physically impressive, he has become addicted to it. Fortunately, his uncle is in a unique situation to sympathize and offer support.

From Perelandra, ch. 16:

Their bodies, he said, were white. But a flush of diverse colours began at about the shoulders and streamed up the necks and flickered over face and head and stood out around the head like plumage or a halo. He told me he could in a sense remember these colours—that is, he would know them if he saw them again—but that he cannot by any effort call up a visual image of them nor give them any name. The very few people with whom he and I can discuss these matters all give the same explanation. We think that when creatures of the hypersomatic kind choose to ‘appear’ to us, they are not in fact affecting our retina at all, but directly manipulating the relevant parts of our brain. If so, it is quite possible that they can produce there the sensations we should have if our eyes were capable of receiving those colours in the spectrum which are actually beyond their range. The ‘plumage’ or halo of the one eldil was extremely different from that of the other. The Oyarsa of Mars shone with cold and morning colours, a little metallic—pure, hard, and bracing. The Oyarsa of Venus glowed with a warm splendour, full of the suggestion of teeming vegetable life.

The faces surprised him very much. Nothing less like the ‘angel’ of popular art could well be imagined. The rich variety, the hint of undeveloped possibilities, which make the interest of human faces, were entirely absent. One single, changeless expression, so clear that it hurt and dazzled him, was stamped on each, and there was nothing else there at all. In that sense their faces were as ‘primitive’, as unnatural, if you like, as those of archaic statues from Aegina. What this one thing was he could not be certain. He concluded in the end that it was charity. But it was terrifyingly different from the expression of human charity, which we always see either blossoming out of, or hastening to descend into, natural affection. Here there was no affection at all: no least lingering memory of it even at ten million years’ distance, no germ from which it could spring in any future, however remote. Pure, spiritual, intellectual love shot from their faces like barbed lightning. It was so unlike the love we experience that its expression could easily be mistaken for ferocity.

Both the bodies were naked, and both were free from any sexual characteristics, either primary or secondary. That, one would have expected. But whence came this curious difference between them? He found that he could point to no single feature wherein the difference resided, yet it was impossible to ignore. One could try—Ransom has tried a hundred times to put it into words. He has said that Malacandra was like rhythm and Perelandra like melody. He has said that Malacandra affected him like a quantitative, Perelandra like an accentual, metre. He thinks that the first held in his hand something like a spear, but the hands of the other were open, with the palms towards him. But I don’t know that any of these attempts has helped me much.

At all events what Ransom saw at that moment was the real meaning of gender. Everyone must sometimes have wondered why in nearly all tongues certain inanimate objects are masculine and others feminine. What is masculine about a mountain or feminine about certain trees? Ransom has cured me of believing that this is a purely morphological phenomenon, depending on the form of the word. Still less is gender an imaginative extension of sex. Our ancestors did not make mountains masculine because they projected male characteristics into them. The real process is the reverse. Gender is a reality, and a more fundamental reality than sex. Sex is, in fact, merely the adaptation to organic life of a fundamental polarity which divides all created beings. Female sex is simply one of the things that have feminine gender; there are many others, and Masculine and Feminine meet us on planes of reality where male and female would be simply meaningless. Masculine is not attenuated male, nor feminine attenuated female. On the contrary, the male and female of organic creatures are rather faint and blurred reflections of masculine and feminine. Their reproductive functions, their differences in strength and size, partly exhibit, but partly also confuse and misrepresent, the real polarity.

All this Ransom saw, as it were, with his own eyes. The two white creatures were sexless. But he of Malacandra was masculine (not male); she of Perelandra was feminine (not female). Malacandra seemed to him to have the look of one standing armed, at the ramparts of his own remote archaic world, in ceaseless vigilance, his eyes ever roaming the earthward horizon whence his danger came long ago. “A sailor’s look,” Ransom once said to me; “you know … eyes that are impregnated with distance.” But the eyes of Perelandra opened, as it were, inward, as if they were the curtained gateway to a world of waves and murmurings and wandering airs, of life that rocked in winds and splashed on mossy stones and descended as the dew and arose sunward in thin-spun delicacy of mist. On Mars the very forests are of stone; in Venus the lands swim.

For now he thought of them no more as Malacandra and Perelandra. He called them by their Tellurian names. With deep wonder he thought to himself, ‘My eyes have seen Mars and Venus. I have seen Ares and Aphrodite.’