Last week I took time to share my “cheat sheet“–a project that began for me on a scrap of paper but slowly grew up into an excel sheet resource that I consult pretty frequently. What I wanted to do was immerse myself in C.S. Lewis’ writing culture (knowing that the publication dates at the front of our books don’t tell much of the story). What can we learn from the cheat sheet?

Last week I took time to share my “cheat sheet“–a project that began for me on a scrap of paper but slowly grew up into an excel sheet resource that I consult pretty frequently. What I wanted to do was immerse myself in C.S. Lewis’ writing culture (knowing that the publication dates at the front of our books don’t tell much of the story). What can we learn from the cheat sheet?

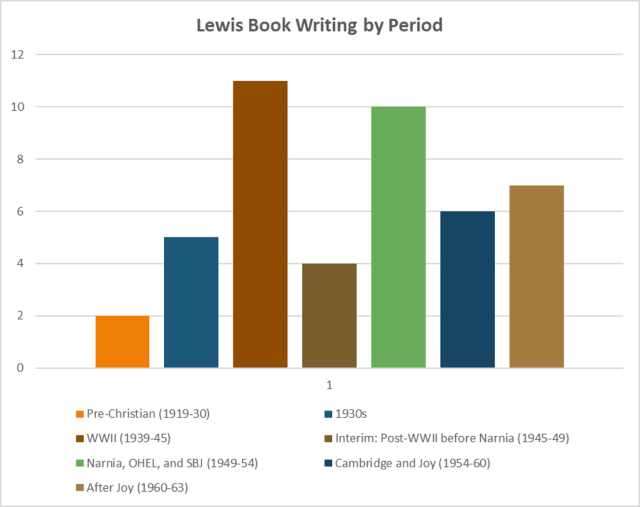

It is obviously a tool that can be adapted by scholars and biographers for their own purposes. And anyone who wants to attempt a chronological reading of C.S. Lewis will find it invaluable. Today, I want to focus in on the periods of Lewis’ life, and the kind of things he produced at different points in his life. I have altered the cheat sheet a bit since last week, and even as I type this up I’m a bit unsatisfied. Should I include Boxen and C. S. Lewis’s Lost Aeneid? What about short pieces that come to light, such as a cluster of reviews that Lewis wrote in the late 20’s and early 30’s? What about things that have emerged from his teaching notebooks? Should his “Great War” letters with Own Barfield in the 20s count as a book fragment? I have left all of these out. Still, I think we see Lewis’ life shape up pretty well in these periods:

| Era | Dates |

| Pre-Christian | Through Oct 1931 |

| 1930s | Oct 1931-Sep 1939 |

| WWII | Sep 1939-Sep 1945 |

| Interim: Post-WWII before Narnia | Sep 1945-Mar 1949 |

| Narnia, OHEL, and Surprised by Joy | Mar 1949-Nov 1954 |

| Cambridge and Joy Davidman | Nov 1954-Jul 1960 |

| After Joy | Jul 1960-Nov 1963 |

When we break his life up into periods, we can get a sense of what defined his life and his work. I have included the full chart below, adding to it a couple of elements that pace his work (the number of months it took to publish each book and essay). Here are some trends that came out of the data for me.

While Lewis was a prolific author, it took him years to develop his literary voice. Lewis endeavoured to be a poet and was thrilled to find his teenage poetry published as a collection, Spirits in Bondage (1919). If there was not a hunger in UK society to hear from war poets, however, it is doubtful that this volume would have found a prominent publisher. When his narrative poem Dymer was finished in 1925, his publisher rejected it. When it was finally published on merit, it sold very poorly, and Lewis set his dream of being a great poet aside. He attempted at least three other narrative poems at the end of the 20s and the early 30s, but he never completed them.

Because Lewis left the long-form poetry behind, doesn’t mean that he became disinterested in telling stories. In The Pilgrim’s Regress (1933), Lewis drew some of his conversion poetry into a piece that he would never replicate in form (allegory) or voice (highly complex and obscure references). After reading David Lindsay, J.B.S. Haldane, and Charles Williams–and taking up a wager with J.R.R. Tolkien–Lewis gave SF writing a try with Out of the Silent Planet (1938). If the conversion allegory was a misstep in literary development, for all its flaws Out of the Silent Planet sets the stage for 15 years of storytelling to follow.

Because Lewis left the long-form poetry behind, doesn’t mean that he became disinterested in telling stories. In The Pilgrim’s Regress (1933), Lewis drew some of his conversion poetry into a piece that he would never replicate in form (allegory) or voice (highly complex and obscure references). After reading David Lindsay, J.B.S. Haldane, and Charles Williams–and taking up a wager with J.R.R. Tolkien–Lewis gave SF writing a try with Out of the Silent Planet (1938). If the conversion allegory was a misstep in literary development, for all its flaws Out of the Silent Planet sets the stage for 15 years of storytelling to follow.

While he would continue to write lyric poetry for the rest of his life, Lewis typically published them under a pseudonym. I have left short book reviews out of my essay treatment (here) and the list below, but in the late 20s Lewis started doing reviews connected with the book that would become The Allegory of Love (1936). These reviews and his literary essays of the 1930s was a testing ground for Lewis’ voice as a literary historian and cultural critic. By the time WWII erupted in Europe, Lewis had trained his voice to meet the public as a controversialist Oxford Don.

It has been noted by biographers, but it is supported by data: C.S. Lewis found his voice as a writer when he surrendered to belief in God and returned to the church in 1930. What an un-reverted Lewis would have produced in his life is unknown to us, but Christianity most certainly energized Lewis in producing a diverse and full catalogue of works.

Book Publication Pace

While Lewis did not begin publishing books in earnest until the late 1930s, he kept a remarkable pace from that point onward, shepherding 45 books to publication (or nearly to publication) in his life. In the 30s, Lewis published a book about every 19 months. In WWII, he increased that pace to a book every 5-6 months. He never quite matched the pace of WWII output in numbers of books, but came close in the Narnian period (a book every 6-7 months) and, intriguingly, during the period after Joy Davidman passed away (a book every 6 months).

Taking into consideration the page counts of the published books–an inaccurate but helpful measure–and we get a clearer image of output. In terms of published pages, taking out reprints, Lewis published 1,000-1,200 pages in each of these four periods: the 1930s, the Interim, Cambridge & Joy, and After Joy. In WWII, Lewis’ published output was 1,772 pages–about 50% higher than normal. In the Narnia period, Lewis produced double his typical output with 2487 published pages (leaving aside his reprint of the various BBC talks as Mere Christianity).

Taking into consideration the page counts of the published books–an inaccurate but helpful measure–and we get a clearer image of output. In terms of published pages, taking out reprints, Lewis published 1,000-1,200 pages in each of these four periods: the 1930s, the Interim, Cambridge & Joy, and After Joy. In WWII, Lewis’ published output was 1,772 pages–about 50% higher than normal. In the Narnia period, Lewis produced double his typical output with 2487 published pages (leaving aside his reprint of the various BBC talks as Mere Christianity).

Beyond these two measures, there is also Lewis’ continual work in writing essays. They largely fall into two camps–Christian essays and literary essays. Overall, Lewis kept a remarkable essay-writing pace. He wrote mostly literary essays in the 1930s at a pace of 2 per year. Beginning at about the start of WWII, Lewis took an interest in apologetics, cultural criticism, and Christian teaching. Must of this interest was focussed on essay writing and other short pieces (like sermons and editorials). All through the two periods that dominated the 1940s, Lewis produced an essay every 6 weeks. This slowed down in the Narnian period, and then increased to a pace of an essay every 9 weeks in the last decade of his life. Intriguingly, the Narnian period is an outlier, where essays dropped to just over 2 per year. Much of this was a drop in academic work: Lewis typically kept a pace of 2-3 literary essays per year, but that dropped to less than 1 per year in the period where he is writing Narnia, OHEL, and his memoir.

What does this teach us? I think there are a few lessons:

The experiences of WWII formed the Lewis we know through a chain of events: Out of the Silent Planet (1938) led to The Problem of Pain (1940) and his work as an apologist. These factors, with The Screwtape Letters (1941) led to the BBC talks and a lot of work in apologetics in the 1940s. Meanwhile, Charles Williams‘ and his own lectures in Paradise Lost led to an academic introduction and Perelandra (1943). Everything seemed to trip forward for Lewis along what seemed like different academic, Christian, and popular pathways. By the end of WWII, it was clear that those pathways were running all along together.

The experiences of WWII formed the Lewis we know through a chain of events: Out of the Silent Planet (1938) led to The Problem of Pain (1940) and his work as an apologist. These factors, with The Screwtape Letters (1941) led to the BBC talks and a lot of work in apologetics in the 1940s. Meanwhile, Charles Williams‘ and his own lectures in Paradise Lost led to an academic introduction and Perelandra (1943). Everything seemed to trip forward for Lewis along what seemed like different academic, Christian, and popular pathways. By the end of WWII, it was clear that those pathways were running all along together. At the end of the war, Lewis turned an editorial eye to those who influenced him, creating an anthology of George MacDonald‘s work and two Charles Williams‘ collections (one which meant editing J.R.R. Tolkien’s famous “On Fairy-stories). When you consider that much Miracles was made up of material disseminated in various forms during WWII, we see how the Interim period is nearly void of fresh writing. It is the only period where he was interested in editing the work of others and where his own imaginative input was thin.

At the end of the war, Lewis turned an editorial eye to those who influenced him, creating an anthology of George MacDonald‘s work and two Charles Williams‘ collections (one which meant editing J.R.R. Tolkien’s famous “On Fairy-stories). When you consider that much Miracles was made up of material disseminated in various forms during WWII, we see how the Interim period is nearly void of fresh writing. It is the only period where he was interested in editing the work of others and where his own imaginative input was thin. Lewis’ sabbatical in 1951-52 clearly contributed to output, allowing him to move Narnia fr0m a couple of books to a full series, and allowing him to finish OHEL. It might be, too, that the step away from academic life gave Lewis some mental space that moved into his memoir writing.

Lewis’ sabbatical in 1951-52 clearly contributed to output, allowing him to move Narnia fr0m a couple of books to a full series, and allowing him to finish OHEL. It might be, too, that the step away from academic life gave Lewis some mental space that moved into his memoir writing.- The sabbatical, however, does not solely explain output in the Narnian period. This was the only period in post-conversion life when he didn’t produce 5-8 essays a year, and it seems that the focus on his long-form fiction and magnum opus academic work paid off–even if it meant that Lewis disappeared from public view.

I don’t think there is any doubt that Mrs. Moore’s death in 1951 freed Lewis up for work. The period of 1951-53 is the most productive of Lewis’ life, save the period of 1941-43.

I don’t think there is any doubt that Mrs. Moore’s death in 1951 freed Lewis up for work. The period of 1951-53 is the most productive of Lewis’ life, save the period of 1941-43.- There isn’t a single lesson about busyness and Lewis’ productivity. When Lewis was healthy, the busy periods seemed to spur him on to great work (like in the WWII period). But the Interim period is a testament that to the fact that competing pressures took their toll. The death of his best friend, the soft response to his 1945-47 books, the explosion of post-war students in Oxford, his brother’s increasingly destructive binges, pressures at home, and (potentially) a public defeat in philosophical debate in 1948 choked out Lewis’ productivity and led to a collapse. The busyness of the WWII period produced much good, while the period of the post-war period produced only exhaustion.

We have an intriguing dark period after Lewis met Joy Davidman and he moved to Cambridge. Joy clearly helped with Till We Have Faces (1956), but it was a couple years later that Lewis produced Reflections on the Psalms (1958). Joy’s influence touches the entire period as she helped shape Till We Have Faces and encouraged the academic books that would fill his last 5 years of work. Still, this 1956 space is an intriguing emptiness.

We have an intriguing dark period after Lewis met Joy Davidman and he moved to Cambridge. Joy clearly helped with Till We Have Faces (1956), but it was a couple years later that Lewis produced Reflections on the Psalms (1958). Joy’s influence touches the entire period as she helped shape Till We Have Faces and encouraged the academic books that would fill his last 5 years of work. Still, this 1956 space is an intriguing emptiness.- Is it surprising that after Joy’s death he turned to writing? A Grief Observed (1961) is a small project that followed her death, but almost immediately

Lewis pinned An Experiment in Criticism and worked on editing his essays (which are suggestive of a new period, I think, should Lewis have lived).

Lewis pinned An Experiment in Criticism and worked on editing his essays (which are suggestive of a new period, I think, should Lewis have lived). - It looks to me, given the productivity, that after his illness in 1962, that Lewis was moving forward with new work in 1963. Had he lived, what would have written?

- After his early 30s, Lewis rarely began anything that he didn’t complete (or kept nothing of what he didn’t think he would complete). I have looked through his remaining sketchbooks, where he tried out various ideas, voices, poems, lectures, book outlines, and introductions. But when he took something to a substantial beginning, he either finished it or burned it.

Though Lewis produced books and essays at a furious pace, what most don’t know is that they often took a long time:

Though Lewis produced books and essays at a furious pace, what most don’t know is that they often took a long time:

- His two books of poetry represented at least 4 years each of concentrated work.

- The Pilgrim’s Regress was written in 2 weeks but included poetry from 2 years of work.

- The Allegory of Love is about 7 years of effort.

- Each of his edited volumes composed 5-15 years of essays.

Miracles was made up of essays and speeches over a 3-4 year period, then was abridged in 1958 and revised in 1959 for an (unusual) 2nd edition.

Miracles was made up of essays and speeches over a 3-4 year period, then was abridged in 1958 and revised in 1959 for an (unusual) 2nd edition.- The Magician’s Nephew was begun in 1948 or 1949, and was the only book of the Narniad that Lewis struggled with. Though published 2nd last after 5+ years of work–and though it is 1st in American editions–it was completed last.

- OHEL was commisioned in 1935 and the last bits were completed in 1953, representing 18 years of scholarly work.

Surprised by Joy was probably written quickly in 1954, but Lewis had been attempting to write a memoir since at least 1930.

Surprised by Joy was probably written quickly in 1954, but Lewis had been attempting to write a memoir since at least 1930.- Till We Have Faces flowed quickly with Joy Davidman as writing partner, but the central story had been in Lewis’ mind for decades.

- The Four Loves was written as a lecture series in 1958 and then adapted to a book in 1959, but began as a germ of an idea in the mid-1930s.

- In the early 1940s Lewis tried to think about a book on prayer, but it didn’t come until he turned to epistolary fiction again in 1963, producing Letters to Malcolm.

- The Discarded Image, Lewis’ last and one of his most enduring works of literary history, began as lectures in as early as 1934.

C.S. Lewis was a terrifyingly efficient writer. Moreover, he was committed to book publication, and he was almost constantly shepherding a book through the stages of conception, writing, editing, publication correspondence, or proofs. In his three biggest periods–WWII, Narnia, and After Joy–he had a book or essay published every 5 or 6 weeks. It is a tremendous accomplishment.

Even though I produced the chart below this morning, I have already begun adapting it (adding page numbers). I’m also trying to figure out a timeline feature to add all the publication points on a single line. It will, I think, be a project that takes me longer than most of Lewis’ books. I hope you find Lewis’ books more interesting than my analysis, but if the analysis helps–or if you can offer corrections or additions–do let me know.

Bks=Books Complete; Frags=Significant Fragments published later; Mo/Bk=how many months on average it took to publish a book; Mo/Ess=how many months on average it took to publish an essay; Mo/Lit=how many months on average it took to publish a literary essay. Do note the difference between publication year and the year(s) Lewis was working on the project. I have left the pre-Christian period out of some of the analysis. This chart doesn’t include books of Lewis’ works that were not edited by him.

Bks=Books Complete; Frags=Significant Fragments published later; Mo/Bk=how many months on average it took to publish a book; Mo/Ess=how many months on average it took to publish an essay; Mo/Lit=how many months on average it took to publish a literary essay. Do note the difference between publication year and the year(s) Lewis was working on the project. I have left the pre-Christian period out of some of the analysis. This chart doesn’t include books of Lewis’ works that were not edited by him.

Very helpful data! Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the note, Paul. You (literally) wrote the book on Narnia resources. This is more for the nerds in behind.

LikeLike

Fascinating stuff! And a call to all writers to put in the work!

I want to add a brief comment on A Preface to Paradise Lost that my English teacher when I studied Eng Lit for A Level encouraged me to read. I was in my pre Christian conversion stage, searching for something to make sense of my life, and was entirely convinced by Lewis’s argument about why Satan appears as a more attractive character than God in Paradise Lost. My defences were slowly coming down. Thank you, Mr Hills!

LikeLike

Interesting story, Stephen. Cool story. What I find interesting about that book is the response it elicits from good readers. Harold Bloom is a bit sarcastic about it, but generally when I meet scholars and Milton readers they often say, “Well, no, I don’t think he’s right, but wow, what a marvellous book!” Less occasionally they agree with him, but he has the advantage of being mentioned in most Milton books but readable by most normal humans.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was very interesting to read – thanks for the data and analysis. Whichever way I look at it, C.S. Lewis was prolific, he certainly set the benchmark high!

LikeLike

Yes, pretty intense.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: That Hideous Graph – Idiosophy

Pingback: That Hideous Graph: Joe Hoffman Enhances the Data from my C.S. Lewis Writing Schedule Cheatsheet | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Lent Day 24 | A Pastor's Thoughts

Pingback: A Miraculous Find: C.S. Lewis First Editions | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Bethlehem as the Hingepoint of History: C.S. Lewis’ Christmas Revolution Poem | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: 2018: A Year of Reading: The Nerd Bit | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: C.S. Lewis in The Christian Century | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Some Follow-up on the Statistical Analysis of C.S. Lewis’ Letters | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: A Timeline of C.S. Lewis’ Major Talks | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: An Obituary of C.S. Lewis’ Life as an Oxford Don, by John Wain (The 65th Anniversary of Lewis’ Death) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “A Sense of the Season”: C.S. Lewis’ Birthday Pivot and the Cambridge Inaugural Address | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “The Planets” in C.S. Lewis’ Writing, with a Planet Narnia Chart (Throwback Thursday) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: It is Easy to Teach C.S. Lewis’ “Till We Have Faces,” but It’s Hard to Blog About It | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien: Friendship, True Myth, And Platonism,” a Paper by Justin Keena | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: The Poets Behind C.S. Lewis’ Paragraph about WWI (On Remembrance Day, with Wilfred Owen) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: An Obituary of C.S. Lewis’ Life as an Oxford Don, by John Wain (The 57th Anniversary of Lewis’ Death) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “Joy Beyond the Walls of the World, Poignant as Grief,” with J.R.R. Tolkien and Frederick Buechner | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Share with Me a Woman’s Voice on Shakespeare, with Thoughts on The Merchant of Venice | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “The Country Around Edgestow”: A Map from C.S. Lewis’ That Hideous Strength by Tim Kirk from Mythlore | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Why is Tolkien Scholarship Stronger than Lewis Scholarship? Part 2: Literary Breadth and Depth | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Have an extra $30,000/£22,000? 1st Edition of That Hideous Strength signed by C.S. Lewis for George Orwell–With Some Notes on Collecting C.S. Lewis | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “The Personal Heresy” and C.S. Lewis’ Autoethnographic Instinct: An Invitation to Intimacy in Literature and Theology (Congress2021 Paper) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “The Personal Heresy” and C.S. Lewis’ Autoethnographic Instinct: An Invitation to Intimacy in Literature and Theology | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: 5 Affordable Ways to Purchase Digital Books By and About C.S. Lewis | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: Splendour in the Dark: C. S. Lewis’s Dymer in His Life and Work by Jerry Root (Hansen Lecture) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: A Life of C.S. Lewis in 20 Minutes: Videos, Timelines, and Resource Articles (Throwback Thursday) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: The C.S. Lewis Studies Series: Where It’s Going and How You Can Contribute | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “A Sense of the Season”: C.S. Lewis’ Birthday Pivot and the Cambridge Inaugural Address (Updated) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “A Sense of the Season”: C.S. Lewis’ Birthday Pivot and the Cambridge Inaugural Address (Updated 2021) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Minor point of clarification! He DID actually finish The Nameless Isle and The Queen of Drum (two narrative poems). He didn’t finish Launcelot. 🙂

LikeLike

He never *published* any of them, is perhaps what you meant to say. ….

LikeLike

Pingback: “The 80th Anniversary of C.S. Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters” by Brenton Dickieson | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: John Bunyan’s Apology for his Book with a Note from C.S. Lewis on Writing as Holistic Discovery–and How Narnia Achieved the Bigness You See | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: “A Sense of the Season”: C.S. Lewis’ Birthday Pivot and the Cambridge Inaugural Address (Updated 2022) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: A Rationale for Teaching C.S. Lewis’ Fiction in The Wrong Order | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: A Brief Note on Many Times and Many Places: C.S. Lewis and the Value of History by Alan Snyder and Jamin Metcalf | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Pingback: An Obituary of C.S. Lewis’ Life as an Oxford Don, by John Wain (on the 60th Anniversary of Lewis’ Death) | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Great piece of analysis! I had the privilege of spending time with one of Lewis’s students from the 1930’s (of course very elderly when I met him); he would absolutely have been present at the lectures on which Lewis based some of the published works you mention.

LikeLike

I have the same experience, but met the student too late in his life, unfortunately. Thanks for the note!

LikeLike