In the warm and appreciative introduction to a festschrift honouring Walter Hooper (1931-2020), C.S. Lewis and the Church (eds., Judith Wolfe and Brendan N. Wolfe), Andrew Cuneo compares Walter Hooper to James Boswell, 9th Laird of Auchinleck and biographer of the greatest curators of English words, Samuel Johnson. Boswell, a younger friend and longtime companion of Dr. Johnson‘s, sought to memorialize the 18th-century writer, editor, and wordhoard-keeper he admired so greatly. Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D. (1791) is full of little anecdotes of Johnson’s articulate and witty sayings, placed in the context of stories about his life, works, and legacy. While not always strictly accurate–we would want to say that Boswell’s Life is often ipsissima vox rather than ipsissima verba, the authentic voice if not always the exact words–Boswell’s biography is so astoundingly entertaining that it continues to be read for its sheer entertainment value, quite apart from any historical or biographical value.

In the warm and appreciative introduction to a festschrift honouring Walter Hooper (1931-2020), C.S. Lewis and the Church (eds., Judith Wolfe and Brendan N. Wolfe), Andrew Cuneo compares Walter Hooper to James Boswell, 9th Laird of Auchinleck and biographer of the greatest curators of English words, Samuel Johnson. Boswell, a younger friend and longtime companion of Dr. Johnson‘s, sought to memorialize the 18th-century writer, editor, and wordhoard-keeper he admired so greatly. Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D. (1791) is full of little anecdotes of Johnson’s articulate and witty sayings, placed in the context of stories about his life, works, and legacy. While not always strictly accurate–we would want to say that Boswell’s Life is often ipsissima vox rather than ipsissima verba, the authentic voice if not always the exact words–Boswell’s biography is so astoundingly entertaining that it continues to be read for its sheer entertainment value, quite apart from any historical or biographical value.

I won’t memorialize the memorial, but C.S. Lewis read the Life of Johnson while under the tutelage of Kirkpatrick, while recovering in the hospital during WWI, and at various times throughout his life. The memoir, Lewis thought, was an occasional book–one to dip into here and there when the time was right. Lewis almost always includes Boswell’s memoir in his lists of great books, and considered Life of Johnson a book friend (see Lewis’ essay, “Kipling’s World”). When his brother Warren was doing WWII work, Lewis sent him a letter, asking this question:

“Do you ever spend an hour on Boswell without finding something new?” (Feb 3, 1940 letter).

So it is not insignificant when Warren, cries out in his journal in 1966, 3 years of the death of the Narnian:

So it is not insignificant when Warren, cries out in his journal in 1966, 3 years of the death of the Narnian:

“With what jealous care I would have Boswellised him.” (Clyde S. Kilby and Marjorie Lamp Mead, eds, Brothers and Friends: An Intimate Portrait of C.S. Lewis, 1982, p. 270; also in the Collected Letters.

Warren brought the first letter collection together with clear biographical intent, but it would be up to others to tell Lewis’ story in detail. Early on, there were folks like publisher Jocelyn Gibb, close friend Owen Barfield, and friend-biographers like Chad Walsh and Roger Lancelyn Green. While Warren was a strong historian in his own right, curating a legacy for his deepest love and deepest loss was not his strength. In time, these other figures had their own work to attend to. The task of curating a legacy then fell to Walter Hooper, Lewis’ late-in-life literary secretary to the man who gave us Narnia and Mere Christianity and The Preface to Paradise Lost.

Owen Barfield & Walter Hooper – 19 Nov. 1985. With permission from the Owen Barfield Literary Estate.

And “curate” is a good word for what Hooper did. He recalls in his essay for the Wake Forest collection that he was initially sent reeling from the blow of Lewis’ untimely death, just shy of this 65th birthday. After all, Hooper said that

“Lewis had been the center of my life since I first came across his writings” a decade before (“Editing C.S. Lewis, Views from Wake Forest, ed. Michael Travers, 2008, 13).

However, Hooper began to work to prove C.S. Lewis and the publishing industry wrong. Lewis was certain he would be forgotten not long after his death, and the publishing industry typically predicts a drop in book sales when one of their authors has passed away. With the publishing advice from Jock Gibb that new books help sell the old ones, Hooper set to work bringing together papers, poems, and letters into various collections.

For someone working full time (as an Anglican chaplain), Hooper’s output in the 1960s is truly remarkable. While helping Warren create a letter-centred biography, Hooper collected Lewis’ variously published or forgotten lyric poems together and published them in 1964. In 1966, Hooper produced two strong literary-critical volumes, the diverse and delightful Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories and the more academic, Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature. Following these moderately successful volumes of Lewis’ (mostly) published papers and talks, Hooper edited Christian Reflections (1967), Selected Literary Essays (1969), and God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics, (1970)–one of the books Hooper worked hardest on, and one of the more important books for providing Christian resources to British and American readers.

For someone working full time (as an Anglican chaplain), Hooper’s output in the 1960s is truly remarkable. While helping Warren create a letter-centred biography, Hooper collected Lewis’ variously published or forgotten lyric poems together and published them in 1964. In 1966, Hooper produced two strong literary-critical volumes, the diverse and delightful Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories and the more academic, Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature. Following these moderately successful volumes of Lewis’ (mostly) published papers and talks, Hooper edited Christian Reflections (1967), Selected Literary Essays (1969), and God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics, (1970)–one of the books Hooper worked hardest on, and one of the more important books for providing Christian resources to British and American readers.

It was also in this period that Hooper supplemented the lyric poetry volume with Narrative Poems (1969), including complete and incomplete story poems that were a large part of Lewis’ early writing life. Hooper rereleased Spirits in Bondage: A Cycle of Lyrics in 1984, with an introduction to one of the more difficult-to-find volumes of Lewis’ materials. Hooper later provided a Collected Poems volume in 1994, though it is Don King’s Collected Poems in 2015 that is what we look to as a critical edition (though it does not include most variants, as a full critical edition would). While I think Chad Walsh’s assessment is true that Lewis is not a great poet, Walsh is right that he is an interesting one, so this editorial work is helpful to readers of Lewis.

It was also in this period that Hooper supplemented the lyric poetry volume with Narrative Poems (1969), including complete and incomplete story poems that were a large part of Lewis’ early writing life. Hooper rereleased Spirits in Bondage: A Cycle of Lyrics in 1984, with an introduction to one of the more difficult-to-find volumes of Lewis’ materials. Hooper later provided a Collected Poems volume in 1994, though it is Don King’s Collected Poems in 2015 that is what we look to as a critical edition (though it does not include most variants, as a full critical edition would). While I think Chad Walsh’s assessment is true that Lewis is not a great poet, Walsh is right that he is an interesting one, so this editorial work is helpful to readers of Lewis.

And so the story goes–or “so the stories go” in Hooper’s case. As the 1970s continued, Walter Hooper expanded his work of publishing papers he found in the archives by turning to some of the more substantial unpublished fictional and nonfictional pieces. The result was the controversial The Dark Tower and Other Stories (1977) and a fan favourite, Past Watchful Dragons: The Narnian Chronicles of C.S. Lewis (1979). Beyond these archive-heavy books, Hooper created early letter collections like They Stand Together: The Letters of C.S. Lewis to Arthur Greeves (1914–1963) (1979), and republished a revised and enlarged Letters of C.S. Lewis, edited with a memoir by W.H. Lewis (1988).

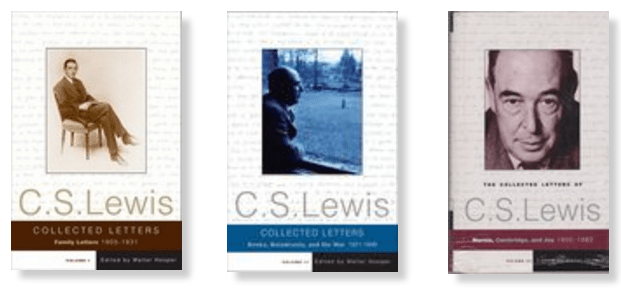

Hooper would produce a dozen or so more volumes of essays and anthologies, so that I needed to create (with the help of Arend Smilde’s work) a spreadsheet and assault plan on the collected short pieces of C.S. Lewis (see here). Ultimately, though, beyond his helpful C.S. Lewis: A Companion and Guide (1996), Hooper’s greatest gift to scholars and biographers is the substantial project of letter publication in three volumes:

Hooper would produce a dozen or so more volumes of essays and anthologies, so that I needed to create (with the help of Arend Smilde’s work) a spreadsheet and assault plan on the collected short pieces of C.S. Lewis (see here). Ultimately, though, beyond his helpful C.S. Lewis: A Companion and Guide (1996), Hooper’s greatest gift to scholars and biographers is the substantial project of letter publication in three volumes:

- C.S. Lewis: Collected Letters, Volume 1: Family Letters (1905–1931), 2004.

- C.S. Lewis: Collected Letters, Volume 2: Books, Broadcasts and War (1931–1949), 2004.

- C.S. Lewis: Collected Letters, Volume 3: Narnia, Cambridge and Joy (1950–1963), 2007.

Carefully edited, easy to read and write notes in, restrained in editorial comments, reasonably complete, and now digitally available (though the 3rd volume is tough to find in print), the letters have lit up Lewis scholarship, providing a depth of knowledge about Lewis that the biographies have not been able to catch. At more than 4000 pages of letters, explanatory notes, biographies, and indices, it is a researcher’s dream resource.

I have included my working Walter Hooper bibliography below, but his production is astounding–creating books at a rate of one every 13 or 14 months until the end of the -90s, and spending much of the first decade of this century editing the Collected Letters. Since the three-volume publication of the Collected Letters in 2007, new C. S. Lewis essays, fragments, literary variants, unfinished stories, marginalia, letters, poems, interviews, and photographs have appeared in steady succession. Others have come alongside Lewis’ literary secretary to bring new work to the world, including monographs by Clyde Kilby, Marjorie Lamp Mead, and Don King–not to mention dozens of pieces, poems, and fragments recently published by folks like Crystal Hurd, Norbert Feinendegen, Arend Smilde, Steven Beebe, Bruce Johnson, David Downing, Diana Pavlac Glyer, Andrew Lazo, and Charlie W. Starr. I have been given a small part of that work, but it still is not anything like the depth that Walter Hooper has given us.

I have included my working Walter Hooper bibliography below, but his production is astounding–creating books at a rate of one every 13 or 14 months until the end of the -90s, and spending much of the first decade of this century editing the Collected Letters. Since the three-volume publication of the Collected Letters in 2007, new C. S. Lewis essays, fragments, literary variants, unfinished stories, marginalia, letters, poems, interviews, and photographs have appeared in steady succession. Others have come alongside Lewis’ literary secretary to bring new work to the world, including monographs by Clyde Kilby, Marjorie Lamp Mead, and Don King–not to mention dozens of pieces, poems, and fragments recently published by folks like Crystal Hurd, Norbert Feinendegen, Arend Smilde, Steven Beebe, Bruce Johnson, David Downing, Diana Pavlac Glyer, Andrew Lazo, and Charlie W. Starr. I have been given a small part of that work, but it still is not anything like the depth that Walter Hooper has given us.

Even if we appreciate that editorial work, it is easy to think about Hooper’s publication story in linear terms: Hooper found and published the pieces; now I get to read them. The result of the work is not linear, however, but algorithmic. People like Stephanie Derrick, Sam Joeckel, Alan Snyder, and George Marsden have chronicled the more complex stories of how Lewis grew from an interesting but obscure don to an international bestseller. It does not take long in Lewis studies to know that Walter Hooper’s own legacy is complicated and messy. In terms of the positive output, though, Gibb’s premise about how new books help sell old ones was precisely correct. Hooper was largely responsible for creating a steady stream of new materials for fans new and old to discover in their local bookshops. While there is some hyperbole in the first part of the following statement, Cuneo’s assessment as a whole is not far off.

“That there is a C.S. Lewis legacy is for the most part due to Hooper’s work; that several generations of readers have a living link to C.S. Lewis is due to his generosity. I know of no twentieth- or twenty-first-century editor who has done anything comparable” (Cuneo, C.S. Lewis and the Church: Essays in Honour of Walter Hooper 1).

In brief form, I argue that Hooper filled seven key roles in helping establish Lewis readership for the next generation:

Compiler: When it comes to the management of his own papers, C.S. Lewis might be among the worst modern historical figures of note. Long before the benefits of searchable PDFs and a Googleplex of possible digital tools, Hooper spent years in the archives, looking for early work, stray papers, and publications no one knew about. The result was that readers had dozens of pieces that would have mouldered in memory until the digital age. God in the Dock, Present Concerns, The Collected Poems, the major academic collections, and gems like Of Other Worlds (or On Stories or Of This and Other Worlds) are primarily made up of pieces Hooper gathered over the years in sitting at a desk and thumbing through popular magazines and academic journals.

Compiler: When it comes to the management of his own papers, C.S. Lewis might be among the worst modern historical figures of note. Long before the benefits of searchable PDFs and a Googleplex of possible digital tools, Hooper spent years in the archives, looking for early work, stray papers, and publications no one knew about. The result was that readers had dozens of pieces that would have mouldered in memory until the digital age. God in the Dock, Present Concerns, The Collected Poems, the major academic collections, and gems like Of Other Worlds (or On Stories or Of This and Other Worlds) are primarily made up of pieces Hooper gathered over the years in sitting at a desk and thumbing through popular magazines and academic journals. Archivist: Or perhaps “Archival Revealer” is a better title. Over the years, Hooper has found in paper collections and in archives dozens of valuable pieces–from snatches of poetry to incomplete novels, from lecture notes to books left unfinished. Among my favourite discoveries are the Narnian bits in Past Watchful Dragons: The Narnian Chronicles of C.S. Lewis, which I describe in my bibliography below. The Dark Tower collection is a combination of these new archival revelations and stories in American science fiction magazines that may have gone unread. There are also the letters which he collected from far and wide, including various archives, libraries, and collections. And even when most of the more glamorous work was done, he was still publishing new letters or lists or resources, some of which I catalogue below.

Archivist: Or perhaps “Archival Revealer” is a better title. Over the years, Hooper has found in paper collections and in archives dozens of valuable pieces–from snatches of poetry to incomplete novels, from lecture notes to books left unfinished. Among my favourite discoveries are the Narnian bits in Past Watchful Dragons: The Narnian Chronicles of C.S. Lewis, which I describe in my bibliography below. The Dark Tower collection is a combination of these new archival revelations and stories in American science fiction magazines that may have gone unread. There are also the letters which he collected from far and wide, including various archives, libraries, and collections. And even when most of the more glamorous work was done, he was still publishing new letters or lists or resources, some of which I catalogue below. Anthologist: Beyond compiling original collections of new and rediscovered materials, in the ’80s and ’90s Hooper created various anthologies like The Business of Heaven and Readings for Meditation and Reflection. While Hooper was not alone in the sort of endeavour–what Christian publisher wouldn’t want to put out an easily digestible collection of Lewis’ best?–countless readers have found C.S. Lewis’ works through a church or family gift book like these.

Anthologist: Beyond compiling original collections of new and rediscovered materials, in the ’80s and ’90s Hooper created various anthologies like The Business of Heaven and Readings for Meditation and Reflection. While Hooper was not alone in the sort of endeavour–what Christian publisher wouldn’t want to put out an easily digestible collection of Lewis’ best?–countless readers have found C.S. Lewis’ works through a church or family gift book like these. Editor: While the compilation of published materials is one set of skills, editing is another skill altogether. Others could perhaps assess Hooper’s editorial skills more precisely, but his works are functional and accessible. Errors are normal in publication, but Hooper’s editorial work is generally sharp and crisp. I have already given my assessment of what is are the magnum opera of his life, the Collected Letters. No doubt he learned as he went along, but in the fullness of time, his editorial restraint and production have benefited researchers like me.

Editor: While the compilation of published materials is one set of skills, editing is another skill altogether. Others could perhaps assess Hooper’s editorial skills more precisely, but his works are functional and accessible. Errors are normal in publication, but Hooper’s editorial work is generally sharp and crisp. I have already given my assessment of what is are the magnum opera of his life, the Collected Letters. No doubt he learned as he went along, but in the fullness of time, his editorial restraint and production have benefited researchers like me. Publisher: While most of this work is invisible to us, and although Hooper himself admits to being jejune in the publishing industry early on, Hooper made some critical decisions early on that opened up far greater possibilities later. I have already mentioned how Hooper committed himself to regular fresh books, knowing that it would invite readers to Lewis’ back catalogue. He also made some technical decisions that may have benefitted the estate and cleverly chose an American evangelical publisher for God in the Dock. But the single stroke of genius was the deal he struck with publishing magnate, Lady Collins. Hooper authorized the reprinting of Lewis’ most popular books on the condition that the publishers also reprint something that is far less popular. While it was a risk for publishers like Collins, it was one that paid off for everyone–especially the readers, who were able to read books like The Abolition of Man that may have been only accessible in the pirated photocopied versions that passed around 20th-century Lewis societies.

Publisher: While most of this work is invisible to us, and although Hooper himself admits to being jejune in the publishing industry early on, Hooper made some critical decisions early on that opened up far greater possibilities later. I have already mentioned how Hooper committed himself to regular fresh books, knowing that it would invite readers to Lewis’ back catalogue. He also made some technical decisions that may have benefitted the estate and cleverly chose an American evangelical publisher for God in the Dock. But the single stroke of genius was the deal he struck with publishing magnate, Lady Collins. Hooper authorized the reprinting of Lewis’ most popular books on the condition that the publishers also reprint something that is far less popular. While it was a risk for publishers like Collins, it was one that paid off for everyone–especially the readers, who were able to read books like The Abolition of Man that may have been only accessible in the pirated photocopied versions that passed around 20th-century Lewis societies. Before-speaker: A “before-speaker” is my word for preface writer, from Latin praefationem, “fore-speaking”, quite literally, “introduction,” from past participle stem of praefari “to say beforehand,” from prae “before” (see pre-) + fari “speak,” from the Proto-Indo-European bha-, where we get saying-aloud words like fable, fame, polyphony, professor, prophet (or the opposite, like nefandous, nefarious, cacophony, or blasphemy), as well as words like “fate” or “fairy”–see, I’m lost in the words, in the details, before we have even gotten to the point! While the prefaces Hooper wrote for Lewis’ edited volumes are admittedly a little rose-tinged, and Screwtape prefaces were proliferating for a period, these before-text words are generally informative and short. Moreover, Hooper has written dozens of forewords and prefaces for scholars and editors trying to do their bit to share something interesting with the world.

Before-speaker: A “before-speaker” is my word for preface writer, from Latin praefationem, “fore-speaking”, quite literally, “introduction,” from past participle stem of praefari “to say beforehand,” from prae “before” (see pre-) + fari “speak,” from the Proto-Indo-European bha-, where we get saying-aloud words like fable, fame, polyphony, professor, prophet (or the opposite, like nefandous, nefarious, cacophony, or blasphemy), as well as words like “fate” or “fairy”–see, I’m lost in the words, in the details, before we have even gotten to the point! While the prefaces Hooper wrote for Lewis’ edited volumes are admittedly a little rose-tinged, and Screwtape prefaces were proliferating for a period, these before-text words are generally informative and short. Moreover, Hooper has written dozens of forewords and prefaces for scholars and editors trying to do their bit to share something interesting with the world. Mentor: Finally, while most people will not know this, Walter Hooper made himself available to hundreds of students, editors, publishers, writers, journalists, biographers, film-makers, scholars, and committed fans over the years. I have seen his visitor books, filled with names of people from around the world. My name is there too. But within these pages are a select few whom Hooper has shaped and mentored over the years. I do not know if anyone will fill his shoes, but he has helped innumerable people in finding their own voice and locating their own way.

Mentor: Finally, while most people will not know this, Walter Hooper made himself available to hundreds of students, editors, publishers, writers, journalists, biographers, film-makers, scholars, and committed fans over the years. I have seen his visitor books, filled with names of people from around the world. My name is there too. But within these pages are a select few whom Hooper has shaped and mentored over the years. I do not know if anyone will fill his shoes, but he has helped innumerable people in finding their own voice and locating their own way.

I have no doubt that, like Warren, Hooper wanted to “Boswellize” the writer he loved so deeply–and a figure in whom we have some interest as well. Frankly, though, when it comes to the art of the biography, Hooper’s C.S. Lewis: A Biography (1974) with Roger Lancelyn Green is not the best. It lacks the vivacity of Green’s storytelling and the energy of Hooper’s great breadth of knowledge; thus for me it lacks much of Lewis’ ipsissima vox, though it is strong on ipsissima verba. The facts are largely in place now, so it is the authentic voice I care most about. I want Lewis-the-man and Lewis-the-poet to come leaping off the page when I read about him–bounding into my own story the way that Aslan evaded Lewis’ imagination at some point in 1948 or 1949. Instead, Green & Hooper’s biography is flat and useful, setting an important stage for more to come. Hooper was not a Boswell to what we can argue is the 20th-century’s Samuel Johnson, C.S. Lewis. And, by now, all those who might have been are dead.

I have no doubt that, like Warren, Hooper wanted to “Boswellize” the writer he loved so deeply–and a figure in whom we have some interest as well. Frankly, though, when it comes to the art of the biography, Hooper’s C.S. Lewis: A Biography (1974) with Roger Lancelyn Green is not the best. It lacks the vivacity of Green’s storytelling and the energy of Hooper’s great breadth of knowledge; thus for me it lacks much of Lewis’ ipsissima vox, though it is strong on ipsissima verba. The facts are largely in place now, so it is the authentic voice I care most about. I want Lewis-the-man and Lewis-the-poet to come leaping off the page when I read about him–bounding into my own story the way that Aslan evaded Lewis’ imagination at some point in 1948 or 1949. Instead, Green & Hooper’s biography is flat and useful, setting an important stage for more to come. Hooper was not a Boswell to what we can argue is the 20th-century’s Samuel Johnson, C.S. Lewis. And, by now, all those who might have been are dead.

But I do not mourn the Boswellian loss for what has come to be a Hooperian result. Andrew Cuneo has once again captured the point:

“I do not think it a stretch to say that the friend and editor of C.S. Lewis to whom this book is dedicated, Walter Hooper, has done more in his own steady way than Boswell himself” (Cuneo, C.S. Lewis and the Church: Essays in Honour of Walter Hooper 1).

That is precisely it: Whatever Walter Hooper’s intentions, he has become Lewis’ better-than-Boswell, for he has provided us with the materials that Lewis himself wrote. I think that is what we have showed up for anyway. It is thus a loss to the Lewis studies community and the end of an era. Lewis’ late-in-life teamaker and posthumous legend-maker is gone, but time will tell who will continue to shape the world’s perception of that rooted and enigmatic figure, C.S. Lewis.

That is precisely it: Whatever Walter Hooper’s intentions, he has become Lewis’ better-than-Boswell, for he has provided us with the materials that Lewis himself wrote. I think that is what we have showed up for anyway. It is thus a loss to the Lewis studies community and the end of an era. Lewis’ late-in-life teamaker and posthumous legend-maker is gone, but time will tell who will continue to shape the world’s perception of that rooted and enigmatic figure, C.S. Lewis.

A Select Bibliography of Walter Hooper’s Published Works (Brenton’s Working Version)

A Select Bibliography of Walter Hooper’s Published Works (Brenton’s Working Version)

Monographs by Walter Hooper:

- C.S. Lewis: A Biography, co-authored with Roger Lancelyn Green, 1974.

- Study guide to The Screwtape Letters with Owen Barfield, 1976; there is an audiobook of The Screwtape Letters around his time with Walter Hooper’s voice in the introduction and introducing the chapters; see also Lord & King American editions of The Screwtape Letters with illustrations by Wayland Moore and Hooper’s revised Study Guide in the paperback version; see also Hooper’s 1982 released of Screwtape with “Screwtape Proposes a Toast” and “the New Preface” Lewis wrote in 1960.

- Past Watchful Dragons: The Narnian Chronicles of C.S. Lewis, 1979, including some archival pieces:

- “Outline of Narnian history so far as it is known,” 41-44.

- “Plots”, 46 (rough sketch of The Voyage of the Dawn Treader).

- “The Lefay Fragment,” 48-65.

- “Eustace’s Diary,”68-71.

- Pauline Baynes-C.S. Lewis correspondence, 77-80.

- Through Joy and Beyond: The Life of C.S. Lewis, co-authored with Anthony Marchington, 1979; there is a 1982 illustrated edition of this book, Through Joy and Beyond: A Pictorial Biography of C.S. Lewis and, allegedly, a documentary

- C.S. Lewis: A Companion and Guide, 1996; there is also a 1998 C.S. Lewis: A Complete Guide to His Life and Works, which is more difficult to find, but the Companion is a critical volume

Walter Hooper’s Edited Volumes of C.S. Lewis’s Works (most of which have prefaces by Hooper):

Diary and Juvenilia

- Boxen: The Imaginary World of the Young C.S. Lewis, with Warren Lewis, 1985 (various editions now exist).

- All My Road Before Me: The Diary of C.S. Lewis, 1922–27, 1991.

Essay and Short Piece Collections

Essay and Short Piece Collections

- Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories, 1966.

- Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature, 1966.

- Christian Reflections, 1967.

- Selected Literary Essays, 1969.

- God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics, 1970.

- Fern-seed and Elephants, and Other Essays on Christianity, 1975.

- The Dark Tower and Other Stories, 1977.

- The Weight of Glory and Other Addresses, revised, expanded, and introduced by Walter Hooper, 1980.

- Of This & Other Worlds. London: Collins, 1982.

- On Stories, and Other Essays on Literature, 1982.

- Present Concerns, 1986.

- Christian Reunion and Other Essays, 1990.

- Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories, 1994.

- Image and Imagination, 2013.

- They Stand Together: The Letters of C.S. Lewis to Arthur Greeves (1914–1963), 1979.

- Letters of C.S. Lewis. Edited with a memoir by W.H. Lewis, revised and enlarged by Walter Hooper, 1988.

- C.S. Lewis: Collected Letters, Volume 1: Family Letters (1905–1931), 2004.

- C.S. Lewis: Collected Letters, Volume 2: Books, Broadcasts and War (1931–1949), 2004.

- C.S. Lewis: Collected Letters, Volume 3: Narnia, Cambridge and Joy (1950–1963), 2007.

- The Business of Heaven: Daily Readings from C.S. Lewis. San Diego: Harcourt, 1984.

- C.S. Lewis: Readings for Meditation and Reflection, 1992.

- The Christian Way: Readings for Reflection, 1999.

Poetry

- Poems, 1964.

- Narrative Poems, 1969.

- Spirits in Bondage: A Cycle of Lyrics, 1984.

- The Collected Poems of C.S. Lewis. London: Fount, 1994.

Helpful Articles (Alphabetical Order):

Helpful Articles (Alphabetical Order):

- “Bibliography of the Writings of C.S. Lewis” in Jock Gibb, ed. Light on C.S. Lewis (1964).

- “It All Began with a Picture: The Making of C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia,” in C.S. Lewis and His Circle: Essays and Memoirs from the Oxford C.S. Lewis Society, edited by Roger White et al., 2015, pp. 150-163.

- “The Lectures of C. S. Lewis in the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge,” Christian Scholar’s Review 27, no. 4 (1998): 436-453.

- “Oxford’s Bonny Fighter” in James T. Como, ed.,S. Lewis at the Breakfast Table (1979), pp. 241-308.

- “Papers and Speakers at the Oxford University Socratic Club”, including a “Revised and Enlarged” version of his “Bibliography of the Writings of C.S. Lewis” in James T. Como, ed.,S. Lewis at the Breakfast Table (1979), pp. 293-308; 387-498.

- “Reminiscences,” Mythlore 3, no. 4 (1976): 5-9.

- “‘Warnie’s Problem’: An Introduction to a Letter from C.S. Lewis to Owen Barfield,” The Journal of Inklings Studies 5, no. 1 (2015): 3-19.

See especially the prefaces to God in the Dock, The Weight of Glory, and The Dark Tower.

Here is a talk by Walter Hooper at the Kilns, captured by David Beckman and hosted by Will Vaus, which I happened to attend.