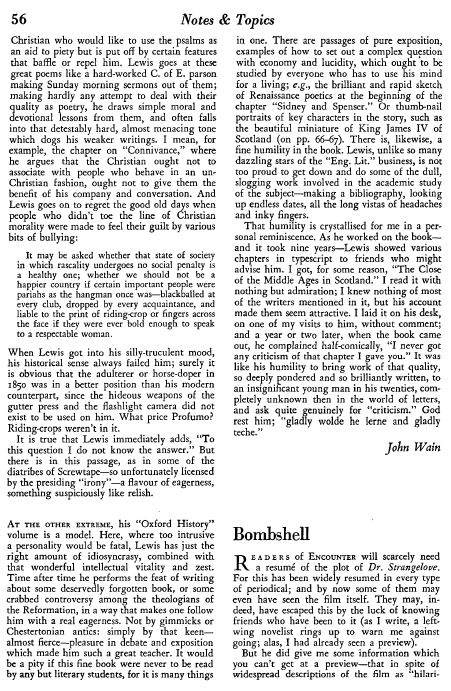

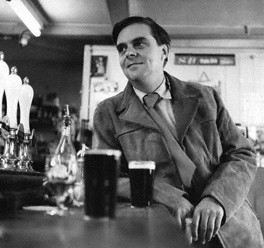

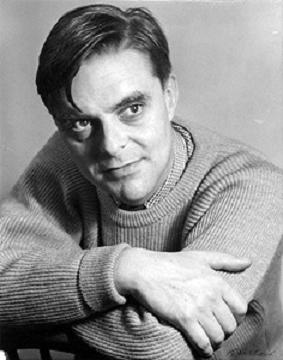

Today is the 57th anniversary of C.S. Lewis’ death. In past years, I have reflected upon Lewis dying in the shadows of great men like JFK and Aldous Huxley on 11/22/63. This year, I wanted to share an obituary of Lewis that most may not have access to. This is the memory of C.S. Lewis as a teacher and public figure, by poet-novelist-critic-playwright John Wain.

Today is the 57th anniversary of C.S. Lewis’ death. In past years, I have reflected upon Lewis dying in the shadows of great men like JFK and Aldous Huxley on 11/22/63. This year, I wanted to share an obituary of Lewis that most may not have access to. This is the memory of C.S. Lewis as a teacher and public figure, by poet-novelist-critic-playwright John Wain.

In C.S. Lewis studies, John Wain is a complicated character. He comes into Lewis’ story not just as a student, but as someone connected to the Inklings and yet separate from them. Wain was a well-known literary figure whose 1962 memoir, Sprightly Running, raised Lewis’ ire where it touched the Inklings (see Bruce Charlton’s blog post here for more). Wain wasn’t far off the mark, however, and his obituary is engaging reading. Wain was an insider-outsider who could speak with both intimacy and distance in the dynamic and changing milieu of Britain’s 1960s literary scene, of which Wain wanted to see himself as a kind of revolutionary.

I clearly don’t agree with Wain that Lewis’ novels are “simply bad” and that an author’s interest in science fiction is “a reliable sign of imaginative bankruptcy”–but, of course, I reject his thesis that popular writing is bad thinking. But his assessment of the “OHEL” volume on 16th-century literature is quite strong–and leads nicely to his conclusion with a Chaucer quotation, “gladly would he learn and gladly teach.” And I don’t share John Wain’s understanding of how Lewis told his own story, though I understand why Lewis’ old student only saw the veiled Lewis and never the revealed one. Of Lewis’ personal walls of protection against a public life, however, Wain may have something to say. In either case, John Wain’s obituary makes for good reading on this the anniversary of C.S. Lewis’ death on Nov 22nd, 1963.

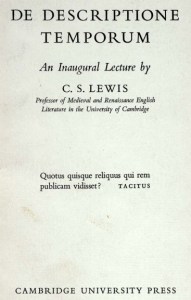

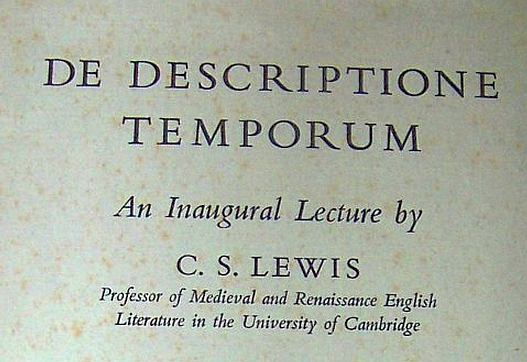

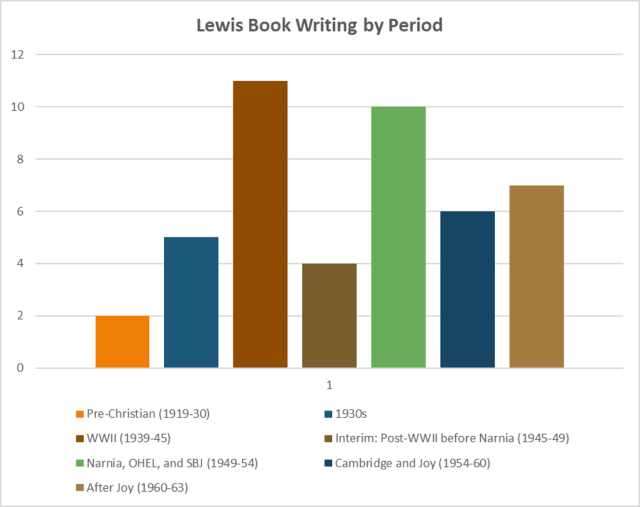

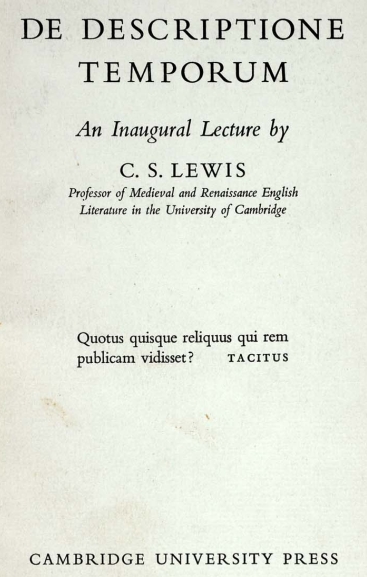

Next week, on Lewis’ 122nd birthday, I will talk more about the “dinosaur” lecture that Wain mentions below. The transcription is my own from the May 1964 Encounter, and I include photographs of it below. The pictures and links are obviously my editorial inclusions, along with some changes in the format (though none of the words). Best wishes on this day of memory.

Most dons, like most schoolmasters, are more or less conscious “characters.” Their lives are lived in the gaze of numerous watchful young eyes, and their ordinary human traits are discussed and commented on by eager young tongues until they become magnified into lovable or laughable idiosyncrasies. Student generations succeed each other so rapidly that by the time a don has been in his post for a mere fifteen years or so, his pupils are being asked by people who seem to them middle-aged, “Is old So-and-so still as such-and-such as ever?” In time, even the most retiring don becomes a legend; his face and voice, walk and gestures, are studied far more intimately than those of a merely public figure such as a politician. For the don is semiprivate. He “belongs to” the university at which he works. His activities are watched and criticised by an audience who feel themselves personally

insulted if he does something they don’t like, personally complimented if they approve.

For this reason every don is equipped with a persona, a set of public characteristics which in time he finds it hard to lay aside even in privacy. After all, the politician who sets up an image simple enough to be adopted by cartoonists, or the “maverick” man of letters who aims to capture the attention of journalists and TV interviewers, need only construct a scarecrow with some faint resemblance to himself.

But the don’s image is tested and scrutinised by alert twenty-year-old eyes, half-a-dozen times a day, in the privacy of his study fireside. It has to be lifelike. It must very nearly approximate to his real character: the mask must have almost the same play of expression as the face beneath it.

So that the don who makes an impact on the wider scene (Gilbert Murray, F. R. Leavis) or becomes a star performer in a mass medium (C. M. Joad, A. J. P. Taylor) starts with a big advantage over the cruder performer from Westminster or Fleet Street. Such men are like Dickens characters. We know they are not real, that no human being was ever quite like that; but we cannot deny that they are true to a certain kind of “nature.”

So that the don who makes an impact on the wider scene (Gilbert Murray, F. R. Leavis) or becomes a star performer in a mass medium (C. M. Joad, A. J. P. Taylor) starts with a big advantage over the cruder performer from Westminster or Fleet Street. Such men are like Dickens characters. We know they are not real, that no human being was ever quite like that; but we cannot deny that they are true to a certain kind of “nature.”

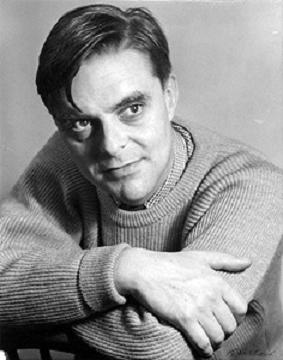

C.S. Lewis was a rare case of the don who is forced into the limelight by the demands of his own conscience. He had a secure academic reputation before beginning that series of popular theological works which made him world-famous; I believe he would never have bothered to court the mass public at all had he not seen it as his duty to defend the Christian faith, to which he became a convert in early adult life, against the hostility or indifference that surrounded it.

Many of his Oxford acquaintances never forgave him for a book like The Screwtape Letters, with its knock-down arguments, its obvious ironies, its journalistic facility. But Lewis used to quote with approval General Booth’s remark to Kipling: “Young man, if I could win one soul for God by playing the tambourine with my toes, I’d do it.” Lewis did plenty of playing the tambourine with his toes, to the distress of some of the refined souls by whom he was surrounded at Oxford.

He had a naturally rhetorical streak in him which made it a pleasure to cultivate the arts of winning people’s attention and assent.

Lewis’ father was a lawyer, and the first thing that strikes one on opening any of his books is that he is always persuading, always arguing a case. If he wrote a book or essay about an author, the assumption was that he had accepted a brief to defend that author. It was his duty to bring the jury round to his point of view by advancing whatever argument would be likely to carry weight with them. It is this, more than anything else, that gives his literary criticism its curious impersonality. We feel that Lewis is simply not interested in telling us what it was that first made him, Lewis, a devotee of Spenser or Milton or William Morris. He consistently attacked what he called “the personal heresy,” and despised the argumentum ad hominem. To him, every important issue lay in the domain of public debate. Whether it was the choice of a book to read or the choice of a God to believe in, Lewis argued the matter like a counsel. His personal motives were kept well back from the reach of curious eyes. All was forensic; the jury were to be won over and that was all.

Lewis’ father was a lawyer, and the first thing that strikes one on opening any of his books is that he is always persuading, always arguing a case. If he wrote a book or essay about an author, the assumption was that he had accepted a brief to defend that author. It was his duty to bring the jury round to his point of view by advancing whatever argument would be likely to carry weight with them. It is this, more than anything else, that gives his literary criticism its curious impersonality. We feel that Lewis is simply not interested in telling us what it was that first made him, Lewis, a devotee of Spenser or Milton or William Morris. He consistently attacked what he called “the personal heresy,” and despised the argumentum ad hominem. To him, every important issue lay in the domain of public debate. Whether it was the choice of a book to read or the choice of a God to believe in, Lewis argued the matter like a counsel. His personal motives were kept well back from the reach of curious eyes. All was forensic; the jury were to be won over and that was all.

For this reason the parts of Lewis’ work that are most disappointing are those that ought to be personal and aren’t. He wrote a great deal about Christian belief, and liked to begin his discourse with, “When I was an atheist.. . .” But the personal revelation was entirely mechanical; the former Lewis had taken a generalised atheistic position, the present-day Lewis took a generalised Christian position. So that when his autobiography, Surprised by Joy, appeared in 1955, many people turned eagerly to the account of his own conversion, hoping at last to have a glimpse of the personal reasons behind it, the reasons that counted for something in the silence of his own heart. The result was disappointment. The account is as lame and unconvincing as it could possibly be. All one brings away from it is the fact that it occurred at Whipsnade.

This inability to share his inner life is of course no disgrace to Lewis. We have suffered too much in this century from men and women who rush in, proffering their souls on a tin plate, eager to button-hole us and “tell all”; and then, in most cases, making up a pack of lies. Lewis would have been too honest to follow their example. And on the rare occasions when some kind of personal element was needed–in his work or in his relationships with people–what held him back was not lack of honesty but simply a deep-seated inhibition which he could not break.

This inability to share his inner life is of course no disgrace to Lewis. We have suffered too much in this century from men and women who rush in, proffering their souls on a tin plate, eager to button-hole us and “tell all”; and then, in most cases, making up a pack of lies. Lewis would have been too honest to follow their example. And on the rare occasions when some kind of personal element was needed–in his work or in his relationships with people–what held him back was not lack of honesty but simply a deep-seated inhibition which he could not break.

Everyone who knew Lewis was aware of this strange dichotomy. The outer self-brisk, challenging, argumentative, full of an overwhelming physical energy and confidence-covered an inner self as tender and as well-hidden as a crab’s. One simply never got near him. It was an easy matter to become an acquaintance, for he was gregarious and enjoyed matching his mind against all comers. And if he liked what he saw of you, it was easy to go further and become a friend–invited to visit him at Magdalen and enjoy many hours of wide-ranging conversation. But the territory was clearly marked. You were made free of a certain area-the scholarly, debating, skirmishing area which the whole world knew. Beyond that, there was a heavily protected inner self which no one ever saw.

No one? Doubtless there were a few, here and there; two or three friends of forty years’ standing, who were of his own generation and shared his Christianity; the wife he married late in life; possibly a few blood-relations. But if anyone ever really knew his inner mind, the secret was well kept.

If anyone doubts this, let him take a look at the book Lewis wrote about the experience of

If anyone doubts this, let him take a look at the book Lewis wrote about the experience of

having to endure his wife’s death and the subsequent religious and philosophical turmoil of his thoughts. It was published by Faber & Faber in 1961 as A Grief Observed, by “N. W. Clerk.” (“N. W.” was Lewis’s signature for the clever pieces of light verse he was at one time in the habit of contributing to Punch; it stands for “nat while’’–more correctly, I think, “hwilc”–which is Anglo-Saxon for “I know not whom.”) This book, evidently composed with a great deal of care as a refuge from grief and a monument to love, is just as impersonal, as non-intimate, as anything signed by Lewis. One gets no impression of the living presence of a real woman. I don’t mean only that we are not told whether she was tall or short, fat or thin. (Though even that would have helped.) The want is subtler.

A palpable human presence is there, but it is the presence of a mind; it has no heartbeat or smell or weight. Characteristically, we are given a description of her mind; it was “lithe and quick and muscular as a leopard. Passion, tenderness, and pain were all unable to disarm it.” Beyond that, nothing.

Not that the book fails to take us into a human situation. Its notes on the psychology of grief are interesting and valuable. But what we see is generalised grief, not one particular man’s. It is what Johnson desiderated for literature, a “just representation of general

nature.”

What caused this withdrawal, this inner timidity, I do not know. I could make a clumsy, amateur effort to psycho-analyse Lewis, but my findings could not be of any clinical value, and in any case I shrink from any such probings; I liked and admired the man, and if he wanted his inner self left alone I think we should leave it alone. I mention the matter only because it is one of the keys to the work he has left us. In his writings Lewis adopts a strongly marked role, for the reasons I gave at the beginning. But this role is a wooden dummy. It bears the individual features of no living man. Lewis grew up in the Edwardian age and his chief allegiances were to that age. He became a Fellow of Magdalen in 1925 and from then on it was easy for him to ignore the modern world; the interior of an Oxford college has probably changed less since Edwardian days than anywhere, always excepting the House of Commons. And even before he got his Fellowship, he had noticed the 1920s only to draw away from them in hostile dissent. From about 1914 onwards, he disliked modern literature because it reflected modern life.

What caused this withdrawal, this inner timidity, I do not know. I could make a clumsy, amateur effort to psycho-analyse Lewis, but my findings could not be of any clinical value, and in any case I shrink from any such probings; I liked and admired the man, and if he wanted his inner self left alone I think we should leave it alone. I mention the matter only because it is one of the keys to the work he has left us. In his writings Lewis adopts a strongly marked role, for the reasons I gave at the beginning. But this role is a wooden dummy. It bears the individual features of no living man. Lewis grew up in the Edwardian age and his chief allegiances were to that age. He became a Fellow of Magdalen in 1925 and from then on it was easy for him to ignore the modern world; the interior of an Oxford college has probably changed less since Edwardian days than anywhere, always excepting the House of Commons. And even before he got his Fellowship, he had noticed the 1920s only to draw away from them in hostile dissent. From about 1914 onwards, he disliked modern literature because it reflected modern life.

This withdrawal from the age he lived in went easily hand in hand with Lewis’ impersonality in human contacts, his construction of a vast system of intellectual outworks to protect the deeply-hidden core of his personality. As time went on, and the younger people he met began to seem more and more Martian (as they do to all of us, goodness knows), Lewis deliberately adopted the role of a survival. He was “Old Western Man,” his attitudes dating from before Freud, before modern art or poetry, before the machine even. When, in 1954, he left Oxford for Cambridge, he introduced himself to his new audience in this role.

You don’t want to be lectured on Neanderthal Man by a Neanderthaler, still less on dinosaurs by a dinosaur. And yet, is that the whole story? If a live dinosaur dragged its slow length into the laboratory, would we not all look back as we fled? What a chance to know at last how it really moved and looked and smelled and what noises it made! And if the Neanderthaler could talk, then, though his lecturing technique might leave much to be desired, should we not almost certainly learn from him some things about him which the best modern anthropologist could never have told us? He would tell us without knowing he was telling.

Hence:

Hence:

Speaking not only for myself but for all other old Western men whom you may meet, I would say, use your specimens while you can. There are not going to be many more dinosaurs.

Such a public application of the grease-paint did him, I believe, no good among the stern, no-nonsense men of Cambridge, who have no time for play-acting. And it must be admitted that there is an element of disabling unreality about the striking of such an attitude. A man born in 1850 might naturally inhabit an older “order”; a man born, as Lewis was, in 1898 could only reconstruct it from boyhood memories and adult reading. Lewis, who was twenty-four in the year that saw the publication of The Waste Land, couldn’t claim to belong to a generation whose taste in poetry, for instance, was formed before Eliot “came along.” His true role was not that of either “Old Western Man” or a dinosaur, but the humbler and more commonplace role of laudator temporis acti [one who praised the past].

Once this has been grasped, the all-pervading contentiousness of Lewis’ writing becomes more explicable. He was fighting a perpetual rearguard action in defence of an army that had long since marched away.

In some respects this may be a valuable thing to do; to be “modern” and up-to-date is not necessarily a good quality–many of the most appalling people have it. On the other hand, Lewis’ parallel about the dinosaur creeping into the laboratory is an unhelpful oversimplification. Lectures given by an Elizabethan critic on Shakespeare would be very

illuminating, but only to scholars who already understood the main points of 16th-century

thought, and wanted clarification on the finer shades. To interpret the masterpieces of one age to the young of another, we need such understanding as we can muster of both ages. As Allen Tate has remarked, “The scholar who tells us that he understands Dryden but makes nothing of Yeats or Hopkins is telling us that he does not understand Dryden.” What Lewis was actually doing, most of the time, was interpreting the past in terms of the Chesterbelloc era as he reconstructed that era in his own mind.

Thus we find him, in an after-dinner speech on Scott (They Asked for a Paper, pp. 98-99), admitting the charge that Scott often turned out work that he knew to be inferior and was quite happy as long as it sold. “There is little sign, even in his best days, of a serious and costly determination to make each novel as good in its own kind as he could make it. And at the end, when he is writing to pay off his debts, his attitude to his work is, by some standards, scandalous and cynical.” And Lewis goes on:

Thus we find him, in an after-dinner speech on Scott (They Asked for a Paper, pp. 98-99), admitting the charge that Scott often turned out work that he knew to be inferior and was quite happy as long as it sold. “There is little sign, even in his best days, of a serious and costly determination to make each novel as good in its own kind as he could make it. And at the end, when he is writing to pay off his debts, his attitude to his work is, by some standards, scandalous and cynical.” And Lewis goes on:

Here we come to an irreducible opposition between Scott’s outlook and that of our more influential modern men of letters. These would blame him for disobeying his artistic conscience; Scott would have said he was obeying his conscience. He knew only one kind of conscience. It told him that a man must pay his debts if he possibly could. The idea that some supposed obligation to write good novels could override this plain, universal demand of honesty, would have seemed to him the most pitiful subterfuge of vanity and idleness, and a prime specimen of that ‘literary sensibility’ or ‘affected singularity’ which he most heartily despised.

Two different worlds here clash. And who am I to judge between them? It may be true, as Curtius has said, that ‘the modern world immeasurably overvalues art’. Or it may be that the modern world is right and that all previous ages have greatly erred in making art, as they did, subordinate to life, so that artists worked to teach virtue, to adorn the city, to solemnize feasts and marriages, to please a patron, or to amuse the people.

The point is gracefully made; but that list of the possible motives for art in the traditional society simply breaks down when we try to appt it to Shakespeare, or Michelangelo, or Beethoven. (Or is Beethoven already corrupted by modernity?) And whatever Curtius may have meant by his remark, do we in the 20th century actually feel that we live in an age that “overvalues” art, or values it at all, for that matter? But how characteristically skilful of Lewis to bring up a big gun in defence of a weak point!

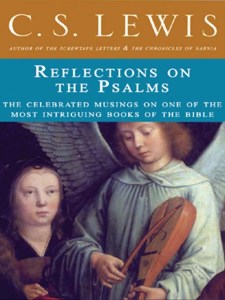

It is early days yet for a final estimate of Lewis’ work, but I think the general view, ultimately, will be that his writing improves as it gets further from the popular and demagogic. Thus, in a miscellany like They Asked for a Paper, the weaker pieces are those in which he could assume an audience less intelligent than himself (e.g., the English Association lecture on Kipling, or the banquet speech about Scott), and the best those in which he addressed himself to some problem before fully qualified people (e.g., the very original and acute “Is Theology Poetry? ”). Setting aside his novels, which I take it are simply bad–he developed in later years a tell-tale interest in science fiction, which is usually a reliable sign of imaginative bankruptcy–think I would put his Reflections on the Psalms at the bottom of the scale, and at the top his contribution to the “Oxford History of English Literature,” English Literature in the Sixteenth Century. The “psalms” volume is frankly popular, addressed to the average Christian who would like to use the psalms as an aid to piety but is put off by certain features that baffle or repel him. Lewis goes at these great poems like a hard-worked C. of E. parson making Sunday morning sermons out of them; making hardly any attempt to deal with their quality as poetry, he draws simple moral and devotional lessons from them, and often falls into that detestably hard, almost menacing tone which dogs his weaker writings. I mean, for example, the chapter on “Connivance,” where he argues that the Christian ought not to associate with people who behave in an un-Christian fashion, ought not to give them the benefit of his company and conversation. And Lewis goes on to regret the good old days when people who didn’t toe the line of Christian morality were made to feel their guilt by various bits of bullying:

It is early days yet for a final estimate of Lewis’ work, but I think the general view, ultimately, will be that his writing improves as it gets further from the popular and demagogic. Thus, in a miscellany like They Asked for a Paper, the weaker pieces are those in which he could assume an audience less intelligent than himself (e.g., the English Association lecture on Kipling, or the banquet speech about Scott), and the best those in which he addressed himself to some problem before fully qualified people (e.g., the very original and acute “Is Theology Poetry? ”). Setting aside his novels, which I take it are simply bad–he developed in later years a tell-tale interest in science fiction, which is usually a reliable sign of imaginative bankruptcy–think I would put his Reflections on the Psalms at the bottom of the scale, and at the top his contribution to the “Oxford History of English Literature,” English Literature in the Sixteenth Century. The “psalms” volume is frankly popular, addressed to the average Christian who would like to use the psalms as an aid to piety but is put off by certain features that baffle or repel him. Lewis goes at these great poems like a hard-worked C. of E. parson making Sunday morning sermons out of them; making hardly any attempt to deal with their quality as poetry, he draws simple moral and devotional lessons from them, and often falls into that detestably hard, almost menacing tone which dogs his weaker writings. I mean, for example, the chapter on “Connivance,” where he argues that the Christian ought not to associate with people who behave in an un-Christian fashion, ought not to give them the benefit of his company and conversation. And Lewis goes on to regret the good old days when people who didn’t toe the line of Christian morality were made to feel their guilt by various bits of bullying:

It may be asked whether that state of society in which rascality undergoes no social penalty is a healthy one; whether we should not be a happier country if certain important people were pariahs as the hangman once was-blackballed at every club, dropped by every acquaintance, and liable to the print of riding crop or fingers across the face if they were ever bold enough to speak to a respectable woman.

When Lewis got into his silly-truculent mood, his historical sense always failed him; surely it is obvious that the adulterer or horse-doper in 1850 was in a better position than his modern counterpart, since the hideous weapons of the gutter press and the flashlight camera did not exist to be used on him. What price Profumo? Riding-crops weren’t in it.

When Lewis got into his silly-truculent mood, his historical sense always failed him; surely it is obvious that the adulterer or horse-doper in 1850 was in a better position than his modern counterpart, since the hideous weapons of the gutter press and the flashlight camera did not exist to be used on him. What price Profumo? Riding-crops weren’t in it.

It is true that Lewis immediately adds, “To this question I do not know the answer.” But there is in this passage, as in some of the diatribes of Screwtape–so unfortunately licensed by the presiding “irony”–a flavour of eagerness, something suspiciously like relish.

At the other extreme, his “Oxford History” volume is a model. Here, where too intrusive a personality would be fatal, Lewis has just the right amount of idiosyncrasy, combined with that wonderful intellectual vitality and zest. Time after time he performs the feat of writing about some deservedly forgotten book, or some crabbed controversy among the theologians of the Reformation, in a way that makes one follow him with a real eagerness. Not by gimmicks or Chestertonian antics: simply by that keen–almost fierce–pleasure in debate and exposition which made him such a great teacher.

It would be a pity if this fine book were never to be read by any but literary students, for it is many things in one. There are passages of pure exposition, examples of how to set out a complex question with economy and lucidity, which ought to be studied by everyone who has to use his mind for a living; e.g., the brilliant and rapid sketch of Renaissance poetics at the beginning of the chapter “Sidney and Spenser.” Or thumbnail portraits of key characters in the story, such as the beautiful miniature of King James IV of Scotland (on pp. 66-67). There is, likewise, a fine humility in the book. Lewis, unlike so many dazzling stars of the “Eng. Lit.” business, is not too proud to get down and do some of the dull, slogging work involved in the academic study of the subject-making a bibliography, looking up endless dates, all the long vistas of headaches and inky fingers.

That humility is crystallised for me in a personal reminiscence. As he worked on the book–and it took nine years–Lewis showed various chapters in typescript to friends who might advise him. I got, for some reason, “The Close of the Middle Ages in Scotland.” I read it with nothing but admiration; I knew nothing of most of the writers mentioned in it, but his account made them seem attractive. I laid it on his desk, on one of my visits to him, without comment; and a year or two later, when the book came out, he complained half-comically, ‘‘I never got any criticism of that chapter I gave you.” It was like his humility to bring work of that quality, so deeply pondered and so brilliantly written, to an insignificant young man in his twenties, completely unknown then in the world of letters, and ask quite genuinely for “criticism.” God rest him; “gladly wolde he lerne and gladly teche.”

I believe in open access scholarship. Because of this, since 2011 I have made A Pilgrim in Narnia free with nearly 1,000 posts on faith, fiction, and fantasy. Please consider sharing my work so others can enjoy it.

It really has been an extraordinary year. For those future readers who haunt these literary halls, 2020 began easily enough. The British were brexiting, the Americans were engulfed in a couple of primaries to see which old white man would compete to rule the known world, and the Canadians were apologizing (and quietly mocking you behind your back). There were destabilized regions in the world, no doubt: enough sorrow and heartache and loneliness to break one’s heart. But that is never new in any new year in our 7-billion person planetary bubble.

It really has been an extraordinary year. For those future readers who haunt these literary halls, 2020 began easily enough. The British were brexiting, the Americans were engulfed in a couple of primaries to see which old white man would compete to rule the known world, and the Canadians were apologizing (and quietly mocking you behind your back). There were destabilized regions in the world, no doubt: enough sorrow and heartache and loneliness to break one’s heart. But that is never new in any new year in our 7-billion person planetary bubble. I suppose we had some hint of things to come. I was in the midst of a 10-part sermon series called “Remembering Heaven,” only to discover how hard it is to talk about heaven when the world is ending all around you. As March began, cases were exploding in Europe and the United States had had its first exposure. In Canada, we had COVID-sufferers quarantining in military bases, but no community spread just yet. On Mar 1st, I preached about creation care, “A Rift in the Rim of the World.” We began livestreaming that day, knowing we had to figure it out so that older folks and those with illness could experience some teaching and singing while staying home. It turns out that it was a wise move, and the tech team at my little local church has spent countless hours this year making things as connected as possible.

I suppose we had some hint of things to come. I was in the midst of a 10-part sermon series called “Remembering Heaven,” only to discover how hard it is to talk about heaven when the world is ending all around you. As March began, cases were exploding in Europe and the United States had had its first exposure. In Canada, we had COVID-sufferers quarantining in military bases, but no community spread just yet. On Mar 1st, I preached about creation care, “A Rift in the Rim of the World.” We began livestreaming that day, knowing we had to figure it out so that older folks and those with illness could experience some teaching and singing while staying home. It turns out that it was a wise move, and the tech team at my little local church has spent countless hours this year making things as connected as possible. On Mar 15th, I gave the last live, in-person sermon of the series, a talk entitled “Fear Not!”–accompanied by a blog post with some of the same themes, “Why the Logic of Prevention will Always Fail for Some: Steady Thoughts in Response to COVID-19.” At the time, I was already seeing the politicization of what was evidently going to be a pandemic as places like the UK and the US destabilized in the midst of a flurry of confused messaging. I was teaching students in New York City online when it suddenly became a hotspot and the city shut down as various states were calling for shelter-in-place orders. Here in Prince Edward Island, the lockdown came just as the first community cases were appearing in Canada. My students scattered throughout the world, getting out if they could, getting in while they were able, and waiting out that first wave in the homes of family and friends–though sometimes in empty dorm rooms, by themselves, with their four walls.

On Mar 15th, I gave the last live, in-person sermon of the series, a talk entitled “Fear Not!”–accompanied by a blog post with some of the same themes, “Why the Logic of Prevention will Always Fail for Some: Steady Thoughts in Response to COVID-19.” At the time, I was already seeing the politicization of what was evidently going to be a pandemic as places like the UK and the US destabilized in the midst of a flurry of confused messaging. I was teaching students in New York City online when it suddenly became a hotspot and the city shut down as various states were calling for shelter-in-place orders. Here in Prince Edward Island, the lockdown came just as the first community cases were appearing in Canada. My students scattered throughout the world, getting out if they could, getting in while they were able, and waiting out that first wave in the homes of family and friends–though sometimes in empty dorm rooms, by themselves, with their four walls.

Personally, I was not really lonely during the lockdown. At first, I was so overwhelmed by work that I could barely think about it. It was amusingly difficult to reign in 100 students in 4 different classes from across the continents so I could help them get across their semester-end finish line. Most of them made it, though students on the edge of failure at mid-term found the challenges of distanced-education and self-regulated workload and tech-necessity too much to bear. I began work early in the morning and worked until late at night–as my wife did, trying to figure out how to teach kindergarten through a screen, and as my son adjusted to grade 10 in a remote emergency educations system.

Personally, I was not really lonely during the lockdown. At first, I was so overwhelmed by work that I could barely think about it. It was amusingly difficult to reign in 100 students in 4 different classes from across the continents so I could help them get across their semester-end finish line. Most of them made it, though students on the edge of failure at mid-term found the challenges of distanced-education and self-regulated workload and tech-necessity too much to bear. I began work early in the morning and worked until late at night–as my wife did, trying to figure out how to teach kindergarten through a screen, and as my son adjusted to grade 10 in a remote emergency educations system. It really was a profound time. It still is. I am astounded by the human casualty due to the pandemic and the pandemic prevention measures. I feel deeply for those who are lost or trapped or in desperation. I wish I could say that I am surprised by the strange, self-serving politicization of COVID responses, but I am saddened by it–particularly as so many of my brothers and sisters in Christ, whose core commandment is to “love God” and “love your neighbour as you love yourself,” continue to speak in terms like “I gotta have my rights, see”–that’s a quote from one of C.S. Lewis’ characters in The Great Divorce–or who trap themselves in conspiratorial mind-prisons that limit their view of the world and show skeptics North American Christianity is really a me-first affair. I’m sad, but I am not surprised.

It really was a profound time. It still is. I am astounded by the human casualty due to the pandemic and the pandemic prevention measures. I feel deeply for those who are lost or trapped or in desperation. I wish I could say that I am surprised by the strange, self-serving politicization of COVID responses, but I am saddened by it–particularly as so many of my brothers and sisters in Christ, whose core commandment is to “love God” and “love your neighbour as you love yourself,” continue to speak in terms like “I gotta have my rights, see”–that’s a quote from one of C.S. Lewis’ characters in The Great Divorce–or who trap themselves in conspiratorial mind-prisons that limit their view of the world and show skeptics North American Christianity is really a me-first affair. I’m sad, but I am not surprised. But what impresses me most–what has shaken my unreflective self-consciousness–is how moved I am by COVID19. It has been a significant career disruption, but I have not lost anyone close to me or suffered any ill effects myself. I live in a safe place, with a loving family and good work to do–whether I am paid for it or not. I have a home and a garden and a church that is doing its dead-level best in the midst of the madness. I am in the best possible space to “do COVID well,” as the young folk say.

But what impresses me most–what has shaken my unreflective self-consciousness–is how moved I am by COVID19. It has been a significant career disruption, but I have not lost anyone close to me or suffered any ill effects myself. I live in a safe place, with a loving family and good work to do–whether I am paid for it or not. I have a home and a garden and a church that is doing its dead-level best in the midst of the madness. I am in the best possible space to “do COVID well,” as the young folk say. But when the world changed, I found it tremendously difficult to accept that change. Intellectually, I was fine. And yet I have remained stirred by this moment from the beginning.

But when the world changed, I found it tremendously difficult to accept that change. Intellectually, I was fine. And yet I have remained stirred by this moment from the beginning. It isn’t just that ordinary existence–“real life” Screwtape calls it sardonically–can distract me from deeper things. No. I have discovered that I am, body and soul, committed to the ordinary. I have always thought that I was not particularly susceptible to Screwtape’s key point about human spiritual life:

It isn’t just that ordinary existence–“real life” Screwtape calls it sardonically–can distract me from deeper things. No. I have discovered that I am, body and soul, committed to the ordinary. I have always thought that I was not particularly susceptible to Screwtape’s key point about human spiritual life:

So that the don who makes an impact on the wider scene (Gilbert Murray, F. R. Leavis) or becomes a star performer in a mass medium (C. M. Joad, A. J. P. Taylor) starts with a big advantage over the cruder performer from Westminster or Fleet Street. Such men are like Dickens characters. We know they are not real, that no human being was ever quite like that; but we cannot deny that they are true to a certain kind of “nature.”

So that the don who makes an impact on the wider scene (Gilbert Murray, F. R. Leavis) or becomes a star performer in a mass medium (C. M. Joad, A. J. P. Taylor) starts with a big advantage over the cruder performer from Westminster or Fleet Street. Such men are like Dickens characters. We know they are not real, that no human being was ever quite like that; but we cannot deny that they are true to a certain kind of “nature.”