My past past few days has been taken up by Canada’s annual Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences, Congress2021–what scholarly Canadians used to call “the Learneds.” It was certainly a learning experience for me–and I am a bit mentally tapped as I start a new week of work.

My past past few days has been taken up by Canada’s annual Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences, Congress2021–what scholarly Canadians used to call “the Learneds.” It was certainly a learning experience for me–and I am a bit mentally tapped as I start a new week of work.

At the Canadian-American Theological Association (CATA), I presented material from my forthcoming book, The Shape of the Cross in C.S. Lewis’ Spiritual Theology. As I hunt for a publisher, this presentation allowed me to return to one of my early discoveries for C.S. Lewis. As CATA is filled with dynamic, bright, and integrative thinkers, I was able to think about the implications of my work both for Lewis studies and for theological method.

I am pleased to be able to share a video of the lecture for you. This video is not of the live conference paper but prepared specially for you. I hope you find it a fruitful discussion. There are some resources below (including abstracts, a PDF of the slides, and links to background reading) that might be helpful.

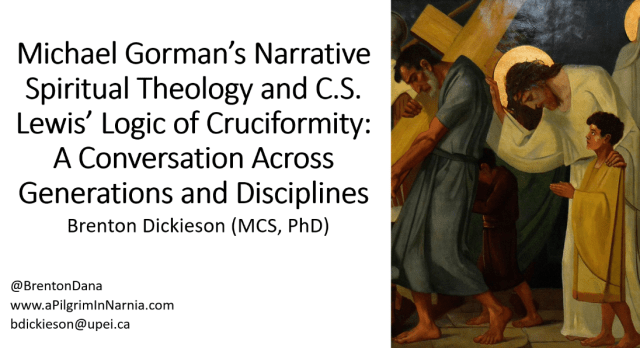

“Michael Gorman’s Narrative Spiritual Theology and C.S. Lewis’ Logic of Cruciformity: A Conversation Across Generations and Disciplines” by Brenton D.G. Dickieson

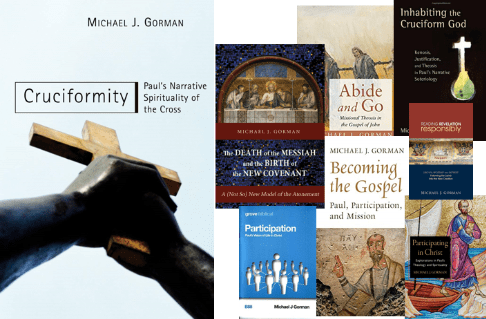

In 2001, Michael J. Gorman produced a ground-breaking study in biblical theology. Cruciformity: Paul’s Narrative Spirituality of the Cross was unique in its focus on Pauline spirituality as revealed in the story patterns within the text. For Paul, the cross is not merely the redemptive hinge of history but also the normative pattern for Christian spirituality. Discipleship is cross-shaped, so the believer’s life echoes the death and resurrection of Christ. Paul captures this cruciform principle of spirituality in narrative patterns of the cross embedded in his letters, speaking less in terms of theological systematization and, more commonly, in terms of pastoral, spiritual theology. The cross event, then, invites believers into narrative unity with Christ in spiritual life.

Though writing as a popular theologian lacking Gorman’s systematic treatment, and writing in an older generation, C.S. Lewis anticipates Gorman’s approach to Pauline narrative spiritual in intriguing ways. There is, I argue, a “Logic of Cruciformity” evident in Lewis’ apologetics trilogy and throughout his corpus. The Pauline cruciform spirituality that Gorman describes is the all-encompassing, integrating narrative reality that informs all of Lewis’s life and works. This proto-theological instinct in Lewis makes Gorman useful for framing Lewis’ ideas into a coherent whole. Moreover, the fact that Lewis’ nonsystematic understanding of Cruciformity is revealed not only in his theological works but also in his popular fiction and literary theory confirms Gorman’s interest in the embedded, storied nature of spirituality and the power of these patterns for creating narrative unity between the cross event and spiritual life.

Here is a PDF of the slides that I will use for my paper: Dickieson-CSL-Gorman Cruciformity CATA 2021.

Checking out my biography will give you a sense of the kinds of things I’m am doing as a theologian of literature and literary theologian. This work will be part of what will appear (hopefully) as The Shape of the Cross in C.S. Lewis’ Spiritual Theology, and came out of my PhD research (which you can read about here). I first discerned the heart of this particular work in the autumn of 2013, preparing for a conference at the Atlantic School of Theology in Halifax, NS (you can see the details here). I wrote my initial findings in a chapter entitled “‘Die Before You Die’: St. Paul’s Cruciformity in C.S. Lewis’s Narrative Spirituality” in Both Sides of the Wardrobe: C.S. Lewis, Theological Imagination, and Everyday Discipleship, edited by Rob Fennell (Eugene, OR: Resource Publications, 2015), pp 32-45. For a popular, brief vision of these findings, see my guest blog post at “Theological Miscellany” of the Westminster Theological Centre.

If you are interested in publishing The Shape of the Cross in C.S. Lewis’ Spiritual Theology, of if you are a researcher looking for the larger, detailed chapter in my embargoed thesis, “The Great Story on Which the Plot Turns”: Cruciformity in C.S. Lewis’ Narrative Spiritual Theology, email me: junkola [at] gmail [dot] com.

Finally, I do recommend Michael Gorman’s biblical-theological works as smart, excellently conceived and executed, and practically oriented.

There are three other Lewis papers at this year’s CSLG:

There are three other Lewis papers at this year’s CSLG: Short Abstract

Short Abstract Longer Abstract

Longer Abstract

Resources for More

Resources for More