I have always loved Ursula K. Le Guin‘s Earthsea Cycle and have mused once about whether I liked Ged or Arha better. Though Earthsea suits me as a fantasy reader, I recognize that Le Guin’s Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed are her great works–and there is a sense of adventure, curiosity, subversiveness, and challenge to her SciFi novels that I love. And I admire Le Guin’s approach to writing speculative fiction, what she calls “lying” in her foreword to my copy of The Left Hand of Darkness–at least theoretically, as I loaned out my copy and it has slipped from my memory.

I have always loved Ursula K. Le Guin‘s Earthsea Cycle and have mused once about whether I liked Ged or Arha better. Though Earthsea suits me as a fantasy reader, I recognize that Le Guin’s Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed are her great works–and there is a sense of adventure, curiosity, subversiveness, and challenge to her SciFi novels that I love. And I admire Le Guin’s approach to writing speculative fiction, what she calls “lying” in her foreword to my copy of The Left Hand of Darkness–at least theoretically, as I loaned out my copy and it has slipped from my memory.

After being prodded by a couple of writerly friends, rather than pick up Earthsea again as a summer read I decided to read the Hainish Cycle in order–the world where The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed are set. In order of publication, this reading begins with Le Guin’s breakout short novel, Rocannon’s World.

The story of an interstellar anthropologist trapped in a pre-technological world under siege by a rogue superpower, Rocannon’s World is the true beginning of Le Guin’s inversive fictional experiment in science and social life. The prologue is a lovely and bittersweet true legend of one woman’s mythic quest. While I enjoy the anthropological elements and outsider-insider perspectives of this book (one of my favourite aspects of The Left Hand of Darkness), I am honestly struggling quite a bit. It isn’t often that I have basic comprehensive issues with a story. I have always wondered at Le Guin’s brevity, but I need a bit more in this text to help me understand what’s going on. What one online reviewer called a “light read” has been for me a bit of a fight.

Ultimately, I used a few of my classic coping mechanisms for hard books.

First, I made a character list–and “characters” in this book include humans, humanoids, other intelligent creatures, semi-sentient creatures, intelligent animals, and personified planets. Making the list has helped me pull the story into place.

Second, I decided to “trust” the book and just keep reading–like we used to trust the voice of the person who read to us as children even if some of the details were hazy. This lap-reading technique has helped. As I move through the story, I find that the details that puzzled me a few pages earlier begin to fall into place. So I chose to stop worrying and learn to love the obscurity.

Third, I wrote about it–just now, what you are reading. Thinking allowed about reading has the effect, for me, of clarifying and helping me enter a text.

So, fourth, I scheduled a conversation with a couple of other smart readers to chat about the novel.

My approach is good overall, but while waiting for the ad hoc book club discussion, I turned to Google for help. There isn’t much there, frankly. But in my digital wanderings, I found Le Guin’s introduction to Ursula K. Le Guin: The Hainish Novels & Stories, Volume One, which is meant to provide a bit of background to the Hainish Cycle. Unsurprisingly for Le Guin, it is an idiosyncratic introduction at best.

But what this piece–which I have retitled “Inventing a Universe is a Complicated Business”–succeeds in doing is giving the reader another invitation to the mental architecture behind the way Le Guin shapes imaginative worlds. While not one of our most precise speculative world-builders, she is one of our more important ones. The worlds she builds have meaning, not just the actions and people in the worlds. And, without fail, in this piece Le Guin offers us such strange and thoughtful ways of looking at the task of telling stories. “God knows inventing a universe is a complicated business,” Le Guin quips at the beginning of this piece–a line that has its own kind of unusual context in her light and thought.

After deprecating herself as a nonmethodical “cosmos-maker,” Le Guin invites us into the story of how her early science fiction writing came about. Here is a unique look at what sets her writing apart:

“I’d been sending fiction out for years to mainstream editors who praised my writing but said they didn’t know what it was. Science fiction and fantasy editors did know what it was, or at least what they wanted to call it. Many of the established figures of the genre were open-minded and generous, many of its readers were young and game for anything. So I had spent a lot of time on that planet.”

And like all emerging authors, Le Guin was haunted by doubt. Even when she sensed there was a story there, she admits that she was not always the best judge of her own work. The book that has changed the way we think about both fiction and relational life, The Left Hand of Darkness, looked to Le Guin like a “natural flop”:

“Its style is not the journalistic one that was then standard in science fiction, its structure is complex, it moves slowly, and even if everybody in it is called he, it is not about men…. The Nebula and Hugo Awards for that book came to me as validation when I most needed it. They proved that among my fellow writers of science fiction, who vote the Nebula, and its readers, who vote the Hugo, I had an audience who did recognise what I was doing and why, and for whom I could write with confidence that they’d let me sock it to them. That’s as valuable a confirmation as an artist can receive. I’d always been determined to write what and as I chose, but now that determination felt less like challenging the opposition, and more like freedom.”

There is an almost accidental and deeply personal reality to Le Guin’s greatness, it seems–and we see this in her other great work:

“The Dispossessed started as a very bad short story, which I didn’t try to finish but couldn’t quite let go.”

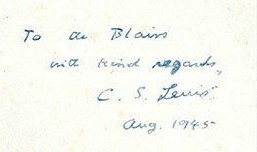

Le Guin reveals to us something about her story-invention process that is likely not a surprise to avid readers. While her stories often begin as sketches of characters or worlds–and Rocannon’s World is limited by a love for the world more than the characters, I think–the stories develop because of certain thought experiments. Using what C.S. Lewis called “imaginative supposals,” Ursula Le Guin plays out the story by wondering what would happen if we re-thought not just gender but sex, not just war but peace, not just love but friendship, not just hatred but entwined enemyship, and so on. The result is that she can flip our expectations of what meeting another culture might be, or how morality might work in different contexts, or how heroism or love or failure can transform not just the world around us but our very selves.

These are her supposals, questions, inversions, experiments of thought for which she is famous.

But there is also what she calls her own “irresponsible” tourism. Le Guin keeps wanting to go back to the worlds she has made, taking more time to live in the environment or with the characters–or to play out in some other time and place the literary experiments that are still unsatisfied. Always the anthropologist, like Rocannon, Genly Ai, and others, Le Guin writes because she longs

“to go back to Gethen at last, and enter a Gethenian kemmerhouse, and find out what people did there. I enjoyed the experience immensely.”

Writing is a kind of discovery for Le Guin, which pleases me deeply. True, it is tougher to keep her worlds together, mentally, than with a more precise cosmos-maker. But it leads her to make sardonic and slightly shocking comments like this:

“Irresponsible as a tourist, I wandered around in my universe forgetting what I’d said about it last time, and then trying to conceal discrepancies with implausibilities, or with silence. If, as some think, God is no longer speaking, maybe it’s because he looked at what he’d made and found himself unable to believe it.”

And then there is Le Guin’s occasional need to complain in a humorous fashion even as she makes an important point, like this gem:

“The word-hound in me protests against the word “prequel”—“sequel” has honest roots, it grew out of Latin sequor, “prequel” is a rootless fake, there isn’t any verb praequor… but it doesn’t matter. What matters most about a word is that it says what we need a word for. (That’s why it matters that we lack a singular pronoun signifying non-male/female, inclusive, or undetermined gender. We need that pronoun.) So “The Day Before the Revolution” is, as its title perhaps suggests, a prequel to the novel The Dispossessed, set a few generations earlier. But it is also a sequel, in that it was written after the novel.”

So I continue with the Hainish Cycle, knowing that in the better and worse there will be some genius, some discomfort, and not a little pleasure. I would encourage you to read this piece by Le Guin. I have included just enough, I hope, to lure you into clicking the link to read on into Le Guin’s imaginative world(s).

“Inventing a Universe is a Complicated Business” by Ursula K. Le Guin

“Inventing a Universe is a Complicated Business” by Ursula K. Le Guin

God knows inventing a universe is a complicated business. Science fiction writers know that re-using one you already invented is a considerable economy of effort, and you don’t have to explain so much to readers who have already been there. Also, exploring farther in an invented cosmos, the author may find interesting new people and places, and perhaps begin to understand its history and workings better. But problems arise if you’re careless about what things happen(ed) when and where.

In many of my science fiction stories, the peoples on the various worlds all descend from long-ago colonists from a world called Hain. So these fictions came to be called “Hainish.” But I flinch when they’re called “The Hainish Cycle” or any such term that implies they are set in a coherent fictional universe with a well-planned history, because they aren’t, it isn’t, it hasn’t. I’d rather admit its inconsistencies than pretend it’s a respectable Future History.

Methodical cosmos-makers make plans and charts and maps and timelines early in the whole process. I failed to do this. Any timeline for the books of the Hainish descent would resemble the web of a spider on LSD. Some stories connect, others contradict. Irresponsible as a tourist, I wandered around in my universe forgetting what I’d said about it last time, and then trying to conceal discrepancies with implausibilities, or with silence. If, as some think, God is no longer speaking, maybe it’s because he looked at what he’d made and found himself unable to believe it.

Usually silence is best….

Read the entire piece here, which is the introduction that Ursula K. Le Guin wrote for Ursula K. Le Guin: The Hainish Novels & Stories, Volume One, edited by that ever-productive fellow, Brian Attebery.

I was pleased last week to have G. Connor Salter provide a piece for the

I was pleased last week to have G. Connor Salter provide a piece for the

A couple of months ago, I wrote about “

A couple of months ago, I wrote about “ “

“