I have to admit that I was a wee bit skeptical when Winged Lion Press editor Bob Trexler asked me if I would consider writing a “blurb” for Jim Como’s new book, Mystical Perelandra: My Lifelong Reading of C.S. Lewis and His Favorite Book.

I have to admit that I was a wee bit skeptical when Winged Lion Press editor Bob Trexler asked me if I would consider writing a “blurb” for Jim Como’s new book, Mystical Perelandra: My Lifelong Reading of C.S. Lewis and His Favorite Book.

It was not Como’s work that concerned me. Como is an expert in rhetoric and one of the founding members of the New York C.S. Lewis Society–the world’s oldest active society for sharing the enjoyment and considering the impact of C.S. Lewis‘ life and work. I got to see Como’s “Very Short Introduction” volume for C.S. Lewis in galley-proofs (for a reason I can no longer remember), and I purchased it as soon as it hit the stories. I have read about 20 of these Very Short Introductions, and I was surprised this little volume was as good as it is. Though the books in the series aim to balance brevity and thoroughness, Como’s C.S. Lewis is peculiarly successful in this respect. He allows for the strong presence of Lewis’ voice within an accessible introduction to Lewis’ life that a few surprising and refreshing moments.

It was not Como’s work that concerned me. Como is an expert in rhetoric and one of the founding members of the New York C.S. Lewis Society–the world’s oldest active society for sharing the enjoyment and considering the impact of C.S. Lewis‘ life and work. I got to see Como’s “Very Short Introduction” volume for C.S. Lewis in galley-proofs (for a reason I can no longer remember), and I purchased it as soon as it hit the stories. I have read about 20 of these Very Short Introductions, and I was surprised this little volume was as good as it is. Though the books in the series aim to balance brevity and thoroughness, Como’s C.S. Lewis is peculiarly successful in this respect. He allows for the strong presence of Lewis’ voice within an accessible introduction to Lewis’ life that a few surprising and refreshing moments.

All well and good. However, with a title like Mystical Perelandra showing up in the midst of a busy term, I took a beat to think about it.

It isn’t the “mysticism” thing–though that might be a stumbling block for some. David C. Downing’s 2005 Into the Region of Awe is at its roots a study of Lewis as a mystic. I admit in my 2014 review (see here) that I found the book both compelling and well-written. Though I don’t see any direct ways it influenced my forthcoming book on Lewis’ spiritual theology (more of that anon), I admitted to David in 2012 that I thought he was on to something. Thus, I wonder if in some way the last decade of my research on Lewis’ “invitation to spiritual life” is complementing Into the Region of Awe. So I am open to the idea of Lewis as a mystic.

It isn’t the “mysticism” thing–though that might be a stumbling block for some. David C. Downing’s 2005 Into the Region of Awe is at its roots a study of Lewis as a mystic. I admit in my 2014 review (see here) that I found the book both compelling and well-written. Though I don’t see any direct ways it influenced my forthcoming book on Lewis’ spiritual theology (more of that anon), I admitted to David in 2012 that I thought he was on to something. Thus, I wonder if in some way the last decade of my research on Lewis’ “invitation to spiritual life” is complementing Into the Region of Awe. So I am open to the idea of Lewis as a mystic.

Honestly, my hesitation was that I didn’t want to read something goofy–as some interpretations of Lewis’ work have been–or even something that isn’t a great read.

Yes, I know, that is pretty judgemental. However, there is a good deal of heartfelt material written about C.S. Lewis, and not all of it is good, beautiful, and true as literature, history, and biography. Indeed, there is something of what Robert MacSwain calls “Jacksploitation” in the publishing industry–a rather cynical play on Lewis’ name and fame to create sales without an honest immersion in his work. This kind of thing strikes me as the literary equivalent of cheap logo lunchboxes and Marlboro Man ads.

Yes, I know, that is pretty judgemental. However, there is a good deal of heartfelt material written about C.S. Lewis, and not all of it is good, beautiful, and true as literature, history, and biography. Indeed, there is something of what Robert MacSwain calls “Jacksploitation” in the publishing industry–a rather cynical play on Lewis’ name and fame to create sales without an honest immersion in his work. This kind of thing strikes me as the literary equivalent of cheap logo lunchboxes and Marlboro Man ads.

However, Como knows his material and he tends to write in a lively style. I decided to take a look at the book.

Rather than another difficult piece of work in a busy term, Mystical Perelandra ended up being both refreshing and thoughtful. It was also a helpful resource as I once again taught C.S. Lewis’ strange and beautiful and puzzling novel of the Ransom Cycle, Perelandra. My “blurb bar” is pretty high, but I was pleased to provide a note for the book and wanted to fill that out a bit here.

In describing a lifetime of reading Perelandra, James Como captures the critic’s dilemma in discussing C.S. Lewis’ singular achievement in ascendent prose in Perelandra:

“To do justice to the mythopoeic depth of the encounter I would have to quote it all.”

I get this. As in a few other startling literary moments–like the “Weight of Glory” sermon, the denouement of The Last Battle, the closing words of An Experiment in Criticism, and resonant high points in The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader–Lewis presents a grand poetic vision that spans many pages but is meant to be taken into imaginations in a single moment of receptivity. Then, it draws us mythically into something truer and deeper and brighter in spiritual life that is beyond poetic possibilities. Maybe this is what poets always do, but in these moments, including in Perelandra, Lewis is using words to draw us beyond what words can do.

I get this. As in a few other startling literary moments–like the “Weight of Glory” sermon, the denouement of The Last Battle, the closing words of An Experiment in Criticism, and resonant high points in The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader–Lewis presents a grand poetic vision that spans many pages but is meant to be taken into imaginations in a single moment of receptivity. Then, it draws us mythically into something truer and deeper and brighter in spiritual life that is beyond poetic possibilities. Maybe this is what poets always do, but in these moments, including in Perelandra, Lewis is using words to draw us beyond what words can do.

Thus, with no little irony, professor of rhetoric James Como provides a book about Perelandra while admitting to the inadequacy of words to describe it.

To do this thing which cannot really be done, Como draws us into the mysterious heart of the reader’s experience with his in Mystical Perelandra. His reflections are an invitation for us to live within rather than merely analyze Lewis’ literary vision. The result is alchemical, poetic, and mercurial–a narrative spiritual theology where we imbibe the transcendent nature of Ransom’s planetary journey through Como’s imaginative, sacramental, life-integrated, mystical experience as a reader. For Como writes of Lewis’ Perelandra that

“no single book intertwines his intellectual and imaginative powers as well as the breadth and depth of the man himself more fully than does Perelandra. It is nothing less than a mini-summa: of the cosmology and mythology of Western Christendom, of spiritual theology (that is, of spiritual formation), and – especially – of an intensely personal mysticism, a side of Lewis insufficiently explored or appreciated. In short, Perelandra is an effusion” (1).

Perelandra is “meta-literary” (4), Como argues–literature that is both immersive and requires immersion in order to experience its full effect. Following Downing and infusing the project both with a critical rhetorical lens and an interest in spiritual theology, “irrupting mysticism” (52) is the motif that Como uses to invite the reader into this fuller experience of Lewis’ heart in Perelandra. To get a sense of what Como is doing chapter 1, “The Tongue is Also a Fire” shows the ways that Como brings together Lewis’ story and writing with his own personal story of transformation in reading Lewis and his expertise as a scholar of words. The result is a startlingly original reconsideration of the story of one of the 20th-century’s most famous converts.

Perelandra is “meta-literary” (4), Como argues–literature that is both immersive and requires immersion in order to experience its full effect. Following Downing and infusing the project both with a critical rhetorical lens and an interest in spiritual theology, “irrupting mysticism” (52) is the motif that Como uses to invite the reader into this fuller experience of Lewis’ heart in Perelandra. To get a sense of what Como is doing chapter 1, “The Tongue is Also a Fire” shows the ways that Como brings together Lewis’ story and writing with his own personal story of transformation in reading Lewis and his expertise as a scholar of words. The result is a startlingly original reconsideration of the story of one of the 20th-century’s most famous converts.

As a writer knowing his limitations as a writer and yet still writing, Como has these moments of ascendency, originality, and circumspection that make the reader’s experience of Mystical Perelandra richer. Here are some examples:

“Upon first reading this passage, I felt meta-theoretical scales drop from my eyes, saw planets line up, heard gears grip into place. My understanding of art deepened exponentially, and then so did my judgments and appreciation” (70).

“These combinations of colors, contours, and experiences; of psychology, cosmology and angelology; of rumination, drama, and violence (both on a floating island and at sea); of

Ransom finally killing the Un-man during a horrific ascent in darkness; his emergence into a world so fresh and beckoning, so utterly glorious – all swept me along through peaks and troughs and loops of excitement, elation, fear and satisfaction” (72)“Lewis’s psychological insights are everywhere, and everywhere organic, though casually posited” (97)

While I quite loved reading this unusual book, there are certain limitations of Mystical Perelandra that leave me wanting a bit more.

While I quite loved reading this unusual book, there are certain limitations of Mystical Perelandra that leave me wanting a bit more.

For example, there are moments that Como is resonating with the work of Lewis scholars, including my own argument about “the shape of story” that he discusses in the second chapter and is a critical section in a section of my thesis. However, Como doesn’t treat Lewis scholarship extensively and he seems occasionally antagonistic to certain approaches. In chapter 3 on “Storytelling,” for example, Como critiques Sanford Schwartz’s book on the Ransom Cycle as being “a torrent of learning” in a small book. Schwartz’s literary criticism is thus contrary to the sympathies of Ransom in Perelandra, Lewis writing Perelandra, and Como writing about Perelandra. Besides a strange irony in the comment about “learning” and small books, Como sets Schwartz’s approach over against the core of the story, which he argues is Ransom’s spiritual development (57). Why the contradistinction? Of any writer, isn’t it true that Lewis integrates intellectual and spiritual development, leaving such dichotomies aside?

We see this binary at the heart of Como’s work, where he reduces “spiritual theology” to “spiritual formation”–leaving behind the theological structure of spiritual life that is the typical definition of spiritual theologians. Contrasting his own definition–and this is why the conversation is important–in a way similar to leading spiritual theologians, Como consistently shows in his analysis that Lewis’ spiritual theology is intellectual and thoughtful as well as active and living, even if he reduces the definition to “spiritual formation.”

Thus, quite beyond literature reviews, Como would have benefited from inviting other voices in to his relatively narrow bibliography–though he captures some of the more popular Lewis studies names.

There are other points where I would have wished that Como leave us some breadcrumbs on the trails that he mentions but does not map for us. In the first part of chapter 2, for example, Como provides a brief essay on Lewis and rhetoric and makes this note:

There are other points where I would have wished that Como leave us some breadcrumbs on the trails that he mentions but does not map for us. In the first part of chapter 2, for example, Como provides a brief essay on Lewis and rhetoric and makes this note:

“his even-handed treatment of rhetorical history in his professional work, his notebooks offer virtually no use of rhetoric that is not derogatory, this in spite of Dante, who called it the ‘the sweetest of all the other sciences’” (36).

I would love to see more of the data on that claim, which I believe on instinct to be correct.

Beyond curiosity, I really need to see proof for Como’s undemonstrated claim that when Mrs Moore died Lewis felt the forgiveness of sins (109). And with other claims that strike me as absurd (Owen Barfield learned nothing from Lewis (79)) or disturbing (“I’ve concluded since that much that we take for madness is actually demonic” (105)), we need the author’s argument so that we can find some way of responding.

Finally, there are sometimes background studies that really need a bit more detail and explanation for most readers, such as his references to Newman, Kierkegaard, Frazer, Jung, and some of the mystics and devotional writers in his conversation.

I understand the limitations of this genre of book. And part of the richness of it as a work of literature itself is the broad, sweeping voice and penetrating observations of a senior scholar reflecting on a lifetime of reading. However, a combination of no footnotes and frayed threads is offputting in a way that is not helpful in Como’s daring and fruitful study.

I understand the limitations of this genre of book. And part of the richness of it as a work of literature itself is the broad, sweeping voice and penetrating observations of a senior scholar reflecting on a lifetime of reading. However, a combination of no footnotes and frayed threads is offputting in a way that is not helpful in Como’s daring and fruitful study.

For Mystical Perelandra is a literary risk, with a title and subtitle that will alienate some readers. For the curious and thoughtful reader of Perelandra, this book is a risk that will make our experience richer. Moreover, why should we limit the kinds of questions that we ask of Lewis’ remarkable experiment in space fantasy? Should our responses to Lewis’ most lyrical journey of mythmaking be limited to critical analysis in academic prose? Should we not also invite the mythopoeic response of the storyteller and the literary artistry of the poet? In providing something of the latter, if we are open to the journey, Como’s reflections on Perelandra transport us, like Ransom, to a world of myth and meaning much greater than a book. We should be grateful to Como for providing his essay and to Winged Lion Press for providing a place for a piece like this.

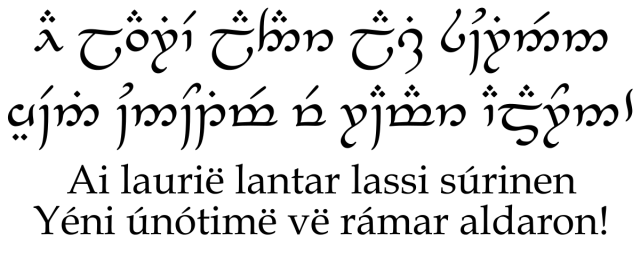

The magnetic oddments served the purpose well, so that when people arrived it was clear to them that I had made what I was calling in my head an “alphabet”—although “alpha” and “beta” had no part in it. The distinctive rhythms and tonal patterns of the Japanese language had entirely infused my mind, but my system didn’t sound like Japanese. It was richer in Ls and Rs, with some gutturals and sibilants from the Hebrew alephbet I was learning at the time. It was the syllabary I wanted to capture from my new culture, not the staccato give and take of Japanese speech–a speech that somehow has contrasts and apologies and the land and something almost monastic hidden in its script.

The magnetic oddments served the purpose well, so that when people arrived it was clear to them that I had made what I was calling in my head an “alphabet”—although “alpha” and “beta” had no part in it. The distinctive rhythms and tonal patterns of the Japanese language had entirely infused my mind, but my system didn’t sound like Japanese. It was richer in Ls and Rs, with some gutturals and sibilants from the Hebrew alephbet I was learning at the time. It was the syllabary I wanted to capture from my new culture, not the staccato give and take of Japanese speech–a speech that somehow has contrasts and apologies and the land and something almost monastic hidden in its script. I can’t remember if I was annoyed at being derivative back then, but I have since become comfortable with that status. When it comes to the constructed languages in fiction (conlangs), Tolkien is the master.

I can’t remember if I was annoyed at being derivative back then, but I have since become comfortable with that status. When it comes to the constructed languages in fiction (conlangs), Tolkien is the master.  Back in 2001, I knew little about Tolkien’s philological idiosyncrasies. I was a fan, reading as a lover of Tolkien’s words and worlds and responding with my own bit of word-playfulness. Good readers do this, I think, sketching out family trees and maps, rewriting the story and playing with its possibilities. And, in the case of a carefully constructed speculative universe with diegetic languages that have some heft, playing with the words of that world is something we love to do.

Back in 2001, I knew little about Tolkien’s philological idiosyncrasies. I was a fan, reading as a lover of Tolkien’s words and worlds and responding with my own bit of word-playfulness. Good readers do this, I think, sketching out family trees and maps, rewriting the story and playing with its possibilities. And, in the case of a carefully constructed speculative universe with diegetic languages that have some heft, playing with the words of that world is something we love to do. As such, Dimitra Fimi and Andrew Higgins’ 2016 publication of J.R.R. Tolkien’s “A Secret Vice” in a critical form is very welcome. A Secret Vice: Tolkien on Invented Language is a beautifully designed edition in the HarperCollins Middle-earth series, and includes critical texts with extensive notes of two of Tolkien’s connected lectures, “A Secret Vice” and “Essay on Phonetic Symbolism.” They also publish a number of related manuscript notes from

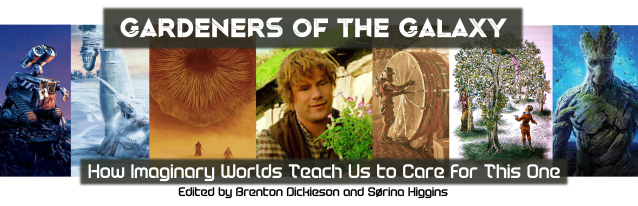

As such, Dimitra Fimi and Andrew Higgins’ 2016 publication of J.R.R. Tolkien’s “A Secret Vice” in a critical form is very welcome. A Secret Vice: Tolkien on Invented Language is a beautifully designed edition in the HarperCollins Middle-earth series, and includes critical texts with extensive notes of two of Tolkien’s connected lectures, “A Secret Vice” and “Essay on Phonetic Symbolism.” They also publish a number of related manuscript notes from  My criticism and concerns are issues of publication rather than editorial control. I am eternally frustrated by endnotes, especially in critical editions. This is even less endearing when we are dealing with conlang poetry. My shout into the wind on this issue will do little to shift what is the normal practice in the industry. Beyond that, the “coda” that offers the section on Tolkien language reception could have been longer. A little more detail about the living nature of Elvin tongues would be welcome, but I am surprised we don’t have a significant portion on what is the most extensive and complete post-Tolkien Tolkienist conlang, that of

My criticism and concerns are issues of publication rather than editorial control. I am eternally frustrated by endnotes, especially in critical editions. This is even less endearing when we are dealing with conlang poetry. My shout into the wind on this issue will do little to shift what is the normal practice in the industry. Beyond that, the “coda” that offers the section on Tolkien language reception could have been longer. A little more detail about the living nature of Elvin tongues would be welcome, but I am surprised we don’t have a significant portion on what is the most extensive and complete post-Tolkien Tolkienist conlang, that of