Since the first time I read C.S. Lewis’ peculiar and beautiful memoir, Surprised by Joy, I have been fascinated by Lewis’ numinous experience of joy that came with his encounter between a moment in Wagner’s Ring Cycle and one of Arthur Rackham’s illustrations. In a sense, A Pilgrim in Narnia has become a curated sandbox to think about the spiritual and artistic importance of this moment in Lewis’ life.

Since the first time I read C.S. Lewis’ peculiar and beautiful memoir, Surprised by Joy, I have been fascinated by Lewis’ numinous experience of joy that came with his encounter between a moment in Wagner’s Ring Cycle and one of Arthur Rackham’s illustrations. In a sense, A Pilgrim in Narnia has become a curated sandbox to think about the spiritual and artistic importance of this moment in Lewis’ life.

One of my early blog posts was, “Balder the Beautiful Is Dead, Is Dead: C.S. Lewis’ Imaginative Conversion.” I really should rewrite that piece. However, I was correct in making links to the Elder Edda–which I connect to my review of Canadian poet Jeramy Dodds’ translation of The Poetic Edda and a note on J.R.R. Tolkien’s Sigurd and Gudrún in what I think to be one of my favourite and least helpful blog titles, “Ragnarök’n’roll!” And I was right to share Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s version of Tegner’s Drapa, for that is where Lewis’ literary imagination had provided the story for what he saw on the page.

While I had some good instincts, I did not find my way to the bottom of the story. I keep writing about it, and it is even behind experimental blog posts like “Lewis, Wagner, and Frankenstein: Literary Accident or Reader’s Providence?” I have also opened this moment of encounter up for some of our guest writers. This encounter is a key feature in Yvonne Aburrow’s piece on Lewis and paganism, “Gods or Angels?“, and is critical to Josiah Peterson’s piece in the “Inklings and King Arthur” series, “Thor: Ragnarok and C.S. Lewis’ Mythic Passions.” Justin Keena moves us even deeper in his paper, “C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien: Friendship, True Myth, And Platonism.” Indeed, all the biographers include this moment in Lewis’ life. For student and friend George Sayer, the “Northernness” that Lewis and Tolkien shared moved deeply inside of him and became part of his own romantic attraction to the Inklings (which I talk about here).

And yet, as this piece by Norbert Feinendegen shows, there is a mystery that has remained unsolved. Norbert is a German philosopher with a particular eye for detail in the most important historical moments of C.S. Lewis’ intellectual journey. As he provokes new questions and finds new clues in the archives, I hope Norbert’s proposal can help fill out this famous moment of Lewis’ teenage life with new richness.

Which Image Triggered C. S. Lewis’ Enthusiasm for Wagner’s Ring Cycle? A Proposal by Norbert Feinendegen

In his autobiography Surprised by Joy, C. S. Lewis recounts a seminal moment that occurred quite early in his life but had an enormous impact on his spiritual development. This encounter of art and imagination has become famous, and yet the image at the centre of the story has remained a mystery.

In his autobiography Surprised by Joy, C. S. Lewis recounts a seminal moment that occurred quite early in his life but had an enormous impact on his spiritual development. This encounter of art and imagination has become famous, and yet the image at the centre of the story has remained a mystery.

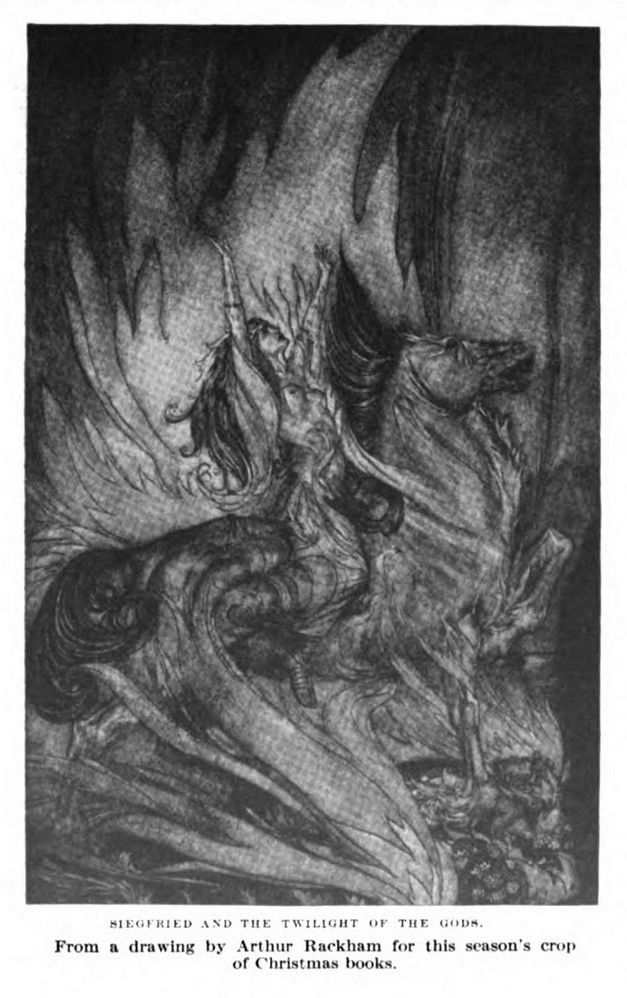

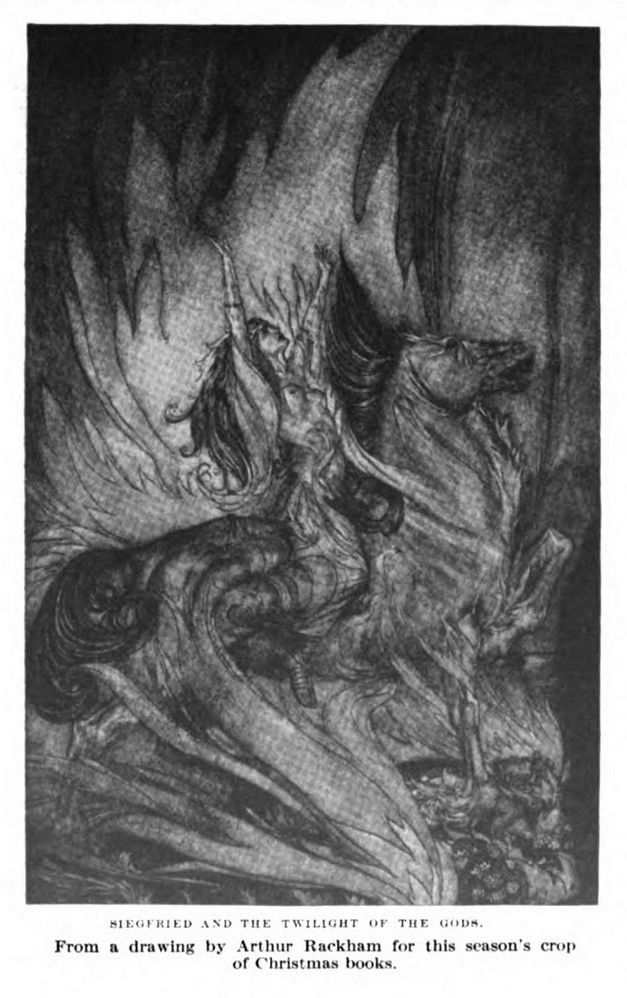

Between January 1911 and July 1913, Lewis was educated at Cherbourg House, Malvern, a preparatory school southwest of Birmingham, England. At some point during these 2 ½ years, his eyes happened to fall on an advertisement in a literary magazine that promoted Volume 2 of Arthur Rackham’s illustrations of Richard Wagner’s Ring des Nibelungen cycle.[1] He saw one of Rackham’s paintings and at the same time read these words: Siegfried and The Twilight of the Gods. This quick glance resulted in an intense experience of Joy – the first since his childhood days – and established his lifelong fascination with Norse mythology.

Lewis gives two accounts of the event. The first is the well-known passage in Chapter 5 “Renaissance” of Surprised by Joy (SbJ):

“This long winter broke up in a single moment, fairly early in my time at Chartres [Cherbourg House]. (…) Someone must have left in the schoolroom a literary periodical: The Bookman, perhaps, or the Times Literary Supplement. My eye fell upon a headline and a picture, carelessly, expecting nothing. A moment later, as the poet says, ‘The sky had turned round’.

“What I had read was the words Siegfried and the Twilight of the Gods. What I had seen was one of Arthur Rackham’s illustrations to that volume. I had never heard of Wagner, nor of Siegfried. I thought the Twilight of the Gods meant the twilight in which the gods lived. How did I know, at once and beyond question, that this was no Celtic, or silvan, or terrestrial twilight? But so it was. Pure ‘Northernness’ engulfed me: a vision of huge, clear spaces hanging above the Atlantic in the endless twilight of Northern summer, remoteness, severity… and almost at the same moment I knew that I had met this before, long, long ago (it hardly seems longer now) in Tegner’s Drapa, that Siegfried (whatever it might be) belonged to the same world as Balder and the sunward-sailing cranes.”

The second account is a passage in “Early Prose Joy” (EPJ), an autobiographical sketch Lewis wrote in late 1930/early 1931 (published by Andrew Lazo in VII, Vol 30 [2013], p. 13-40):

The second account is a passage in “Early Prose Joy” (EPJ), an autobiographical sketch Lewis wrote in late 1930/early 1931 (published by Andrew Lazo in VII, Vol 30 [2013], p. 13-40):

“For two school years of busy and unprofitable boyhood, nothing befell me that concerns the subject of this book. Then all in a moment the frost broke up. I saw one day in a newspaper the reproduction of some picture that Arthur Rackham had drawn for Wagner’s Ring. I suppose that what I was looking at must have been a publisher’s advertisement, for my eyes, at the same moment, took in the words Siegfried and The Twilight of the Gods printed close beside the picture. I had never heard of Wagner, nor of Siegfried: and I thought that ‘the twilight of the gods’ meant the twilight in which the gods lived. It is a little remarkable that though I knew nothing of the Northern mythology till then, save what could be learned from Longfellow, I spontaneously set this twilight and these gods in a place quite apart either from the Celtic or from the Grecian stories. Perhaps the flavour of Rackham’s drawings is truly Germanic and guided me aright. Whatever the cause, those printed words flashed instantly upon my mind a riot of imagery which later knowledge has shown to be surprisingly correct. I saw that twilight hanging pale and motionless over the Atlantic, slowly fading through the endless summer evening of the North: I saw those gods wheeling through it aloft on flying horses: I think (but of this I am uncertain) [that] even then, from some forgotten source, I supplied them with winged helmets.”

Lewis does not say in these two passages which of Rackham’s illustrations he saw, but he assumes in SbJ that the advertisement appeared in The Bookman or The Times Literary Supplement. In both SbJ and EPJ, he emphasises that he saw the illustration and read the words Siegfried and The Twilight of the Gods next to it. Intriguingly, the way that these words sit with the illustration is a fact that has received little attention until now.

According to the Roger Lancelyn Green and Walter Hooper biography of C.S. Lewis (p. 31 in the revised 1994 edition), it was the Christmas edition of The Bookman (December 1911) that fell into Lewis’ hands, which contained a supplement printed in colour with several Rackham illustrations of the Ring.[2] However, a little historical searching shows that this is not so. The “Christmas Double Number” of The Bookman (which is also the December issue) was accompanied by a 138-page “Christmas Supplement” in black and white, as well as by a “Portfolio” with three colour plates by Hugh Thomson (= illustrations for R. B. Sheridan’ The School for Scandal).[3] Neither the 1911 Christmas edition nor the supplement contains any of Rackham’s illustrations for Siegfried & The Twilight of the Gods;[4] the latter does contain an advertisement for the volume on p. 127, but it is not illustrated.[5]

According to the Roger Lancelyn Green and Walter Hooper biography of C.S. Lewis (p. 31 in the revised 1994 edition), it was the Christmas edition of The Bookman (December 1911) that fell into Lewis’ hands, which contained a supplement printed in colour with several Rackham illustrations of the Ring.[2] However, a little historical searching shows that this is not so. The “Christmas Double Number” of The Bookman (which is also the December issue) was accompanied by a 138-page “Christmas Supplement” in black and white, as well as by a “Portfolio” with three colour plates by Hugh Thomson (= illustrations for R. B. Sheridan’ The School for Scandal).[3] Neither the 1911 Christmas edition nor the supplement contains any of Rackham’s illustrations for Siegfried & The Twilight of the Gods;[4] the latter does contain an advertisement for the volume on p. 127, but it is not illustrated.[5]

While Lewis speaks of an advertisement for the Rackham volume, Sayer in his 1988 biography Jack (p. 76 in the 1994 edition) claims that he got hold of a magazine that contained a review of the Rackham volume and featured an illustration: a painting of Siegfried looking down on the sleeping Brünnhilde in the light of the rising sun (whose breastplate he has removed so that her naked breasts are visible, cf. plate 13/30 of Rackham’s illustrations). However, he cites no source for this assertion;[6] on the contrary, he quotes the verses printed in Rackham’s volume on the left-hand page (facing the illustration)[7] and adds that these verses were presumably not reproduced in the review. It therefore appears that Sayer never saw the review himself, which he claims was the trigger for Lewis’ experience.

While Lewis speaks of an advertisement for the Rackham volume, Sayer in his 1988 biography Jack (p. 76 in the 1994 edition) claims that he got hold of a magazine that contained a review of the Rackham volume and featured an illustration: a painting of Siegfried looking down on the sleeping Brünnhilde in the light of the rising sun (whose breastplate he has removed so that her naked breasts are visible, cf. plate 13/30 of Rackham’s illustrations). However, he cites no source for this assertion;[6] on the contrary, he quotes the verses printed in Rackham’s volume on the left-hand page (facing the illustration)[7] and adds that these verses were presumably not reproduced in the review. It therefore appears that Sayer never saw the review himself, which he claims was the trigger for Lewis’ experience.

The actual source of Lewis’ teenage encounter with Northernness appears to have eluded biographers thus far.

After an exhaustive search, I have only been able to find one issue of a contemporary literary journal that contains the combination of illustration and the words Siegfried and The Twilight of the Gods. In the popular US magazine The Literary Digest, a reproduction of plate 29/30 from the Rackham volume appeared on 30 December 1911 with the caption Siegfried and The Twilight of the Gods. The picture shows Brünnhilde in the evening light leaping with her horse Grane onto the funeral pyre on which the dead Siegfried is being burned.

Are there reasons to suppose that it was this illustration that Lewis saw as a young adult? I believe so.

Are there reasons to suppose that it was this illustration that Lewis saw as a young adult? I believe so.

This illustration and caption include both elements of the memory of Balder that triggered joy in Lewis: Rackham’s illustration and the words printed next to it, Siegfried and The Twilight of the Gods. Tegnér’s Drapa[8] says of the dead Balder:

They laid him in his ship,

With horse and harness,

As on a funeral pyre. …

They launched the burning ship!

It floated far away

Over the misty sea,

Till like the sun it seemed,

Sinking beneath the waves.

Balder returned no more!

Here, too, a dead god is handed over to a funeral pyre (and a horse appears). And Longfellow also immerses his scene in the light of the setting sun, which may have provided an additional incentive for Lewis’ (mis)interpretation of the “Twilight of the Gods” as merely evening.[9]

The similarity between the two scenes is unmistakable. This synchronicity could be the reason why Rackham’s image evoked the memory of the dead Balder in Lewis as he intuitively knew that Siegfried belonged to the same world as Balder (the images which came up in him apparently also resembled the imagery of Longfellow’s poem).

The similarity between the two scenes is unmistakable. This synchronicity could be the reason why Rackham’s image evoked the memory of the dead Balder in Lewis as he intuitively knew that Siegfried belonged to the same world as Balder (the images which came up in him apparently also resembled the imagery of Longfellow’s poem).

And there is a second (somewhat less obvious) reason this connection seems likely. In EPJ, Lewis explains his memory of the imaginative encounter:

“I saw that twilight hanging pale and motionless over the Atlantic, slowly fading through the endless summer evening of the North: I saw those gods wheeling through it aloft on flying horses: I think (but of this I am uncertain) [that] even then, from some forgotten source, I supplied them with winged helmets.”

Lewis’ hesitation about the winged helmets suggests that he was certain about the flying horses – that they were part of the original vision and not a later back-projection. Longfellow, who, according to EPJ, was Lewis’ only source for Norse mythology up to that point, does not mention flying horses anywhere. Thus, the question arises as to how Lewis came up with the idea of having his gods fly on horses – unless the picture itself gave him cause to do so.

As it turns out, Brünnhilde on Grane is the only illustration in the volume that shows a deity on a horse. This alone does not explain why Lewis, with his (very vivid) visual imagination, should have seen gods on flying horses. It is conceivable, however, that he had seen paintings of flying gods somewhere else, and that the illustration evoked the memory of these paintings in him. The Edda, which Lewis came to know only afterwards, features horses as mounts of the gods, and Wagner’s Valkyries are also often depicted on flying horses.[10]

After all, we cannot be certain that The Literary Digest was available at Cherbourg House. The Bookman and The Times Literary Supplement are more likely suspects to be found in the school’s library or common room. As we have seen, though, the archives reveal that they contain no illustrations of Siegfried and The Twilight of the Gods.

After all, we cannot be certain that The Literary Digest was available at Cherbourg House. The Bookman and The Times Literary Supplement are more likely suspects to be found in the school’s library or common room. As we have seen, though, the archives reveal that they contain no illustrations of Siegfried and The Twilight of the Gods.

Thus, if Lewis really saw the image of Brünnhilde jumping with Grane onto the funeral pyre of the dead Siegfried, his reaction to both image and title would find an easy explanation. In the spirit of a cautious suggestion, it remains an open question whether Lewis actually saw this image in The Literary Digest or in some other unknown magazine. The combination of Lewis’ description of a Rackham illustration titled with the exact phrase, Siegfried and the Twilight of the Gods, suggests, in my opinion, that we are on the right track. It would be a striking coincidence if another literary journal had published exactly the same combination of image and caption at about the same time.

So the hunt is on: If someone should find the combination of image and title mentioned by Lewis in a British magazine (whether with the same illustration or a different one), and/or should put forward an equally plausible or even more plausible idea of what Lewis might have seen in his schoolroom at Cherbourg House, I’d be delighted – I’m sure we all would be delighted – to hear about it! Meanwhile, when we bring together the autobiography Surprised by Joy with the recently published evidence of “Early Prose Joy,” the Literary Digest advertisement remains strikingly resonant of Lewis’ profound teenage encounter with Northernness.

Norbert Feinendegen has studied philosophy and theology at the philosophical and theological faculties of the RWTH Aachen and Bonn’s Friedrich Wilhelms Universität (State Examination) and holds a PhD in Roman Catholic Theology from the FWU Bonn. He has worked for several years as a research assistant at the Theological Faculty of the University of Bonn and is a freelance author and lecturer in the field of religious education for the Archdiocese of Cologne. He is the author of two German books and several peer-reviewed articles about C. S. Lewis and has published with Arend Smilde The ‘Great War’ of Owen Barfield and C. S. Lewis Philosophical writings 1927-1930 (2015) and C.S. Lewis: Tutor and Lecturer in Philosophy: Philosophical Notes, 1924 (2021). He is advisor to the Owen Barfield Literary Estate and was a long-time board member of the German Inklings Society. His academic work focuses on the philosophy of C. S. Lewis, Christian apologetics, ethics and the relation of faith and science.

Norbert Feinendegen has studied philosophy and theology at the philosophical and theological faculties of the RWTH Aachen and Bonn’s Friedrich Wilhelms Universität (State Examination) and holds a PhD in Roman Catholic Theology from the FWU Bonn. He has worked for several years as a research assistant at the Theological Faculty of the University of Bonn and is a freelance author and lecturer in the field of religious education for the Archdiocese of Cologne. He is the author of two German books and several peer-reviewed articles about C. S. Lewis and has published with Arend Smilde The ‘Great War’ of Owen Barfield and C. S. Lewis Philosophical writings 1927-1930 (2015) and C.S. Lewis: Tutor and Lecturer in Philosophy: Philosophical Notes, 1924 (2021). He is advisor to the Owen Barfield Literary Estate and was a long-time board member of the German Inklings Society. His academic work focuses on the philosophy of C. S. Lewis, Christian apologetics, ethics and the relation of faith and science.

[1] Rackham’s illustrations of Siegfried and the Twilight of the Gods were published in late October 1911, together with Margaret Armour’s recent translation https://archive.org/details/siegfriedtwiligh00wagn/mode/2up. The first volume The Rhinegold and The Valkyrie was published in 1910.

[2] McGrath’s and Poe’s biogaphies make a similar claim but do not cite their sources or add further evidence. While Lewis speaks of only one image, all three (Green/Hooper too) seem to assume that Lewis saw a supplement with several illustrations.

[3] The 1906 Christmas edition of The Bookman, however, contained a Portfolio of three Rackham illustrations of Peter Pan.

[4] The title page of the Christmas Double Number states that it has a cover plate by Edmund Dulac and contains other (unspecified) full-page plates with pictures by Arthur Rackham, Charles Robinson, Claude A. Shepperson and Willy Pogány. However, such plates are neither (!) part of the portfolio, nor of the Christmas edition, nor of the supplement. I have not yet been able to solve this mystery.

[5] The US magazine of the same name (The Bookman), in its Christmas issue 1911, ran a full-page reproduction of plate 1/30 (p. 383), but with the subtitle “SIEGFRIED. BY ARTHUR RACKHAM”.

[6] It is theoretically possible that Lewis told his friend in a personal conversation that it was this painting he saw, but Sayer himself does not make this claim.

[7] “Mystical rapture / Pierces my heart; / Burning with terror; / I reel, my heart faints and fails” (Rackham p. 86). These are Siegfried’s words when, after removing the breastplate, he realises that the person in front of him is not a man but a woman. This four-liner is repeated on the left-hand page opposite the illustration (which is otherwise blank).

[8] https://archive.org/details/poeticalworksofh00long_1/page/216/mode/2up?q=balder

[9] Balder is referred to in Longfellow as the god of the summer sun, so that his burial coincides with the sunset; Lewis’s vision is marked by the fading of the summer evening of the north.

[10] Rackham’s first volume of Ring illustrations The Rhinegold and The Valkyrie also features the Valkyries riding flying horses, but Lewis didn’t see this volume until later. Whether he had a glimpse of this volume before he received it as a Christmas present from his father in 1913 is not known. The painting shown here is by Cesare Viazzi (1857-1943).

I believe in open access scholarship. Because of this, since 2011 I have made A Pilgrim in Narnia free with nearly 1,000 posts on faith, fiction, and fantasy. Please consider sharing my work so others can enjoy it.

Happy Friday fair readers! I am super pleased to announce my new Short Course with the Atlantic School of Theology: “Spirituality in the Writing of L.M. Montgomery.” This May 2022 4-week online audit course is completely open to anyone who is interested. There is still time to sign up and it has an incredibly low registration fee of $20.

Happy Friday fair readers! I am super pleased to announce my new Short Course with the Atlantic School of Theology: “Spirituality in the Writing of L.M. Montgomery.” This May 2022 4-week online audit course is completely open to anyone who is interested. There is still time to sign up and it has an incredibly low registration fee of $20. Spirituality in the Writing of L.M. Montgomery

Spirituality in the Writing of L.M. Montgomery