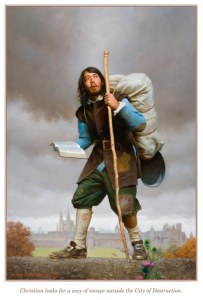

In my blog post last week, “Bunyan and Others and Me: Vicarious Bookshelf Friendship and a Jazz Hands Theory of Reading,” I offered two “Theories of Reading” from my experience of trying to find sympathy with John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress. I know, I know … I seem to be writing a lot about a book I don’t love. Before this reading theory piece, I rewrote my older piece, “The Pilgrim’s Progress and the Nursery Bookshelf: A Book’s Journey“–and I do think this little allegory has a striking pilgrimage as a book. And as I admitted in my reflection piece, “The Sloo/Slow/Sluff of Despond,” there is a good deal of psychological and spiritual truth in John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress–even if I have to work hard to read the book profitably.

In my blog post last week, “Bunyan and Others and Me: Vicarious Bookshelf Friendship and a Jazz Hands Theory of Reading,” I offered two “Theories of Reading” from my experience of trying to find sympathy with John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress. I know, I know … I seem to be writing a lot about a book I don’t love. Before this reading theory piece, I rewrote my older piece, “The Pilgrim’s Progress and the Nursery Bookshelf: A Book’s Journey“–and I do think this little allegory has a striking pilgrimage as a book. And as I admitted in my reflection piece, “The Sloo/Slow/Sluff of Despond,” there is a good deal of psychological and spiritual truth in John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress–even if I have to work hard to read the book profitably.

Well, let me write one more reflection on something I like in this book that eludes my sympathies.

In that “Theories of Reading” posts, I teased up the idea of how we become book friends with authors through other book friends. So many of the writers I like have appreciated The Pilgrim’s Progress. Thus, I keep picking up the book and seeing if this time it will be different.

C.S. Lewis is one of those book friends. Indeed, as a seventeen-year-old describing the his experience of reading, he describes Bunyan’s tale in exactly those terms of friendship:

I am reading at present, what do you think? Our own friend ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’. It is one of those books that are usually read too early to appreciate, and perhaps don’t come back to. I am very glad however to have discovered it. The allegory of course is obvious and even childish, but just as a romance it is unsurpassed, and also as a specimen of real English. Try a bit of your Ruskin or Macaulay after it, and see the difference between diamonds and tinsel (Mar 11, 1916 letter to his father).

Later that year, Lewis tells his friend Arthur Greeves that he was awfully “bucked” to have reread The Pilgrim’s Progress. As with so many other books he discovered in his critical period of faith-loss in 1915 and 1916, Lewis returns to Bunyan in that period of faith-return of 1930-31 before writing his own allegory, A Pilgrim’s Regress, in Arthur’s home in 1932.

In the “Vicarious Bookshelf Friendship and a Jazz Hands Theory of Reading” piece last week, I shared a little of what Lewis does with Bunyan from his later perspective as a literary historian and critic. Intriguingly, Lewis as a teenage Bunyan critic is largely in agreement with Lewis writing as a professional critic in the last months of his life.

In the “Vicarious Bookshelf Friendship and a Jazz Hands Theory of Reading” piece last week, I shared a little of what Lewis does with Bunyan from his later perspective as a literary historian and critic. Intriguingly, Lewis as a teenage Bunyan critic is largely in agreement with Lewis writing as a professional critic in the last months of his life.

For one, Lewis draws Bunyan into the centre of what he thinks is essential Western literature, setting Bunyan next to Dante and Milton and others. While Dante, Spenser, Milton, and Bunyan vie for pride of place in understanding what Lewis was doing in his fiction and scholarship, Lewis connects much more personally to Bunyan, drawing Bunyan’s story into his own emotional life.

And, as we see in the brief note above, from the time he was seventeen, Lewis was able to read The Pilgrim’s Progress at a level deeper than the religious allegory. In his 1962 essay, “The Vision of John Bunyan,” Lewis goes on to consider the allegorist Bunyan, sectarian and fantastic and writing in a chivalric mode, as a model realistic prose writer.

There is another aspect of Lewis’ writing about Bunyan that is worth noting, and that is his observation about how Bunyan found himself writing The Pilgrim’s Progress. Here Lewis explains:

To ask how a great book came into existence is, I believe, often futile. But in this case Bunyan has told us the answer, so far as such things can be told. It comes in the very pedestrian verses prefixed to Part 1. He says that while he was at work on quite a different book he ‘Fell suddenly into an Allegory’. He means, I take it, a little allegory, an extended metaphor that would have filled a single paragraph. He set down ‘more than twenty things’. And, this done, ‘I twenty more had in my Crown’. The ‘things’ began ‘to multiply’ like sparks flying out of a fire. They threatened, he says, to ‘eat out’ the book he was working on. They insisted on splitting off from it and becoming a separate organism. He let them have their head.

It is already an organic process of writing: a little image that becomes many images, sparks lovely and dangerous leaping from a fire, a horse that is ready to gallop and a steady rider who gives it its head. But Lewis narrows in on the humble discovery that speaks to writing beyond the poet Bunyan or his chosen genre. Lewis writes:

It is already an organic process of writing: a little image that becomes many images, sparks lovely and dangerous leaping from a fire, a horse that is ready to gallop and a steady rider who gives it its head. But Lewis narrows in on the humble discovery that speaks to writing beyond the poet Bunyan or his chosen genre. Lewis writes:

Then come the words which describe, better than any others I know, the golden moments of unimpeded composition:

“For having now my Method by the end; Still as I pull’d, it came.”

It came. I doubt if we shall ever know more of the process called ‘inspiration’ than those two monosyllables tell us.

“It came,” which is “the golden moments of unimpeded composition.” Wow, yes. I suspect for most readers, Bunyan captures in two words and Lewis captures in a paragraph of reflection what I was still only grasping at in my 1,500-word essay, “The Thieves of Time and Waking Wonder: Writing as Discovery and the Stone-Carver’s Art.”

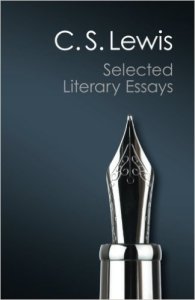

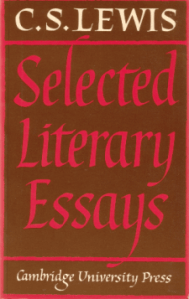

Lewis’ entire essay, “The Vision of John Bunyan,” is worth reading. This reflection originated as a BBC lecture before being published first in The Listener and then in Selected Literary Essays (1969). Unlike most of Lewis’ BBC work, the recording of this piece is available in the archives (with actors reading the Bunyan quotations). Lewis’ voice has a buoyant tone in reading his piece; a “wink” is never far from the surface of the text.

Lewis’ piece, written and recorded at his home at the Kiln’s about a year before he passed away, is an essay in the older sense: an attempt, a teasing out of the implications of an idea. And, if we go to the root of the Latin, it is an idea set in motion, on the way–an experiment of thought set on the road of pilgrimage, if you will. In this essay, Lewis is testing out an argument about Bunyan as a realistic writer rather than specifically a religious writer, and thus is worth reading in full.

Lewis’ piece, written and recorded at his home at the Kiln’s about a year before he passed away, is an essay in the older sense: an attempt, a teasing out of the implications of an idea. And, if we go to the root of the Latin, it is an idea set in motion, on the way–an experiment of thought set on the road of pilgrimage, if you will. In this essay, Lewis is testing out an argument about Bunyan as a realistic writer rather than specifically a religious writer, and thus is worth reading in full.

So although you need the whole piece to get the full sense of Lewis’ interest in the book, I thought it would be useful to provide a bit more of Lewis’ reflections on The Pilgrim’s Progress. Following this, I include Bunyan’s “Apology for his Book,” which makes up in literary self-reflection what it lacks in poetic artistry. It has become my favourite part of the book (which I keep saying, perhaps unconvincingly by now, that I don’t like).

In these selections, we see not only what Lewis noted–the sublime description of “it came” to describe artistic discovery–but also one of the (perhaps unrecognized?) aspects of what Lewis admires in literary art. With no exceptions that I can think of, Lewis has a love of integrative poetry and fiction. In discussing Bunyan, Lewis describes it here as “the whole man,” the bringing together of the “poet” as maker and creator of art, with the “person” as moral agent, wanting to do something in the world. This is, for Lewis, the transcendental combination of “the beautiful” with “the good” that makes a text “true.”

And … can you see it? What Lewis was attempting in Narnia was not as an allegorical or didactic tale. Instead, what he allowed to take place in his own artistic discovery is the integration of the creative writer and Christian neighbour. Lewis’ fairy tales and his spec fic stories are not meant not simply to inspire religious or philosophical or moral or creative ideas, but to also put the story in a new light. In Narnia, this means imagery and story that is not filtered through stained glass.

Thus, there is a striking connection between Lewis’ comments on Bunyan and his own reflections on writing Narnia in pieces like “It All Began with a Picture” and “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s to be Said“–pieces where he describes finding himself falling into a fairy tale, where “it came,” the story emerged, and the moral person took the work of the creative poet and made it into something whole. Or, in Bunyan’s terms, “the bigness which you see”:

For, having now my method by the end,

Still as I pulled, it came; and so I penned

It down: until it came at last to be,

For length and breadth, the bigness which you see.

Selection from C.S. Lewis, “The Vision of John Bunyan”

Perhaps we may hazard a guess as to why it came at just that moment. My own guess is that the scheme of a journey with adventures suddenly reunited two things in Bunyan’s mind which had hitherto lain far apart. One was his present and lifelong preoccupation with the spiritual life. The other, far further away and longer ago, left behind (he had supposed) in childhood, was his delight in old wives’ tales and such last remnants of chivalric romance as he had found in chap-books. The one fitted the other like a glove. Now, as never before, the whole man was engaged.

Perhaps we may hazard a guess as to why it came at just that moment. My own guess is that the scheme of a journey with adventures suddenly reunited two things in Bunyan’s mind which had hitherto lain far apart. One was his present and lifelong preoccupation with the spiritual life. The other, far further away and longer ago, left behind (he had supposed) in childhood, was his delight in old wives’ tales and such last remnants of chivalric romance as he had found in chap-books. The one fitted the other like a glove. Now, as never before, the whole man was engaged.

The vehicle he had chosen – or, more accurately, the vehicle that had chosen him – involved a sort of descent. His high theme had to be brought down and incarnated on the level of an adventure story of the most unsophisticated type – a quest story, with lions, goblins, giants, dungeons and enchantments.

But then there is a further descent. This adventure story itself is not left in the world of high romance. Whether by choice or by the fortunate limits of Bunyan’s imagination – probably a bit of both — it is all visualized in terms of the contemporary life that Bunyan knew. The garrulous neighbours; Mr Worldly-Wiseman who was so clearly (as Christian said) ‘a Gentleman’; the bullying, foul-mouthed Justice; the field-path, seductive to footsore walkers; the sound of a dog barking as you stand knocking at a door; the fruit hanging over a wall which the children insist on eating though their mother admonishes them ‘that Fruit is none of ours’ — these are all characteristic. No one lives further from Wardour Street than Bunyan. The light is sharp: it never comes through stained glass.

And this homely immediacy is not confined to externals. The very motives and thoughts of the pilgrims are similarly brought down to earth…

The Author’s Apology for his Book

The Author’s Apology for his Book

{1} When at the first I took my pen in hand

Thus for to write, I did not understand

That I at all should make a little book

In such a mode; nay, I had undertook

To make another; which, when almost done,

Before I was aware, I this begun.

And thus it was: I, writing of the way

And race of saints, in this our gospel day,

Fell suddenly into an allegory

About their journey, and the way to glory,

In more than twenty things which I set down.

This done, I twenty more had in my crown;

And they again began to multiply,

Like sparks that from the coals of fire do fly.

Nay, then, thought I, if that you breed so fast,

I’ll put you by yourselves, lest you at last

Should prove ad infinitum, and eat out

The book that I already am about.

Well, so I did; but yet I did not think

To shew to all the world my pen and ink

In such a mode; I only thought to make

I knew not what; nor did I undertake

Thereby to please my neighbour: no, not I;

I did it my own self to gratify.

{2} Neither did I but vacant seasons spend

{2} Neither did I but vacant seasons spend

In this my scribble; nor did I intend

But to divert myself in doing this

From worser thoughts which make me do amiss.

Thus, I set pen to paper with delight,

And quickly had my thoughts in black and white.

For, having now my method by the end,

Still as I pulled, it came; and so I penned

It down: until it came at last to be,

For length and breadth, the bigness which you see.

Well, when I had thus put mine ends together,

I shewed them others, that I might see whether

They would condemn them, or them justify:

And some said, Let them live; some, Let them die;

Some said, JOHN, print it; others said, Not so;

Some said, It might do good; others said, No.

Now was I in a strait, and did not see

Which was the best thing to be done by me:

At last I thought, Since you are thus divided,

I print it will, and so the case decided.

{3} For, thought I, some, I see, would have it done,

{3} For, thought I, some, I see, would have it done,

Though others in that channel do not run:

To prove, then, who advised for the best,

Thus I thought fit to put it to the test.

I further thought, if now I did deny

Those that would have it, thus to gratify.

I did not know but hinder them I might

Of that which would to them be great delight.

For those which were not for its coming forth,

I said to them, Offend you I am loth,

Yet, since your brethren pleased with it be,

Forbear to judge till you do further see.

If that thou wilt not read, let it alone;

Some love the meat, some love to pick the bone.

Yea, that I might them better palliate,

I did too with them thus expostulate:–

{4} May I not write in such a style as this?

{4} May I not write in such a style as this?

In such a method, too, and yet not miss

My end–thy good? Why may it not be done?

Dark clouds bring waters, when the bright bring none.

Yea, dark or bright, if they their silver drops

Cause to descend, the earth, by yielding crops,

Gives praise to both, and carpeth not at either,

But treasures up the fruit they yield together;

Yea, so commixes both, that in her fruit

None can distinguish this from that: they suit

Her well when hungry; but, if she be full,

She spews out both, and makes their blessings null.

You see the ways the fisherman doth take

To catch the fish; what engines doth he make?

Behold how he engageth all his wits;

Also his snares, lines, angles, hooks, and nets;

Yet fish there be, that neither hook, nor line,

Nor snare, nor net, nor engine can make thine:

They must be groped for, and be tickled too,

Or they will not be catch’d, whate’er you do.

How does the fowler seek to catch his game

By divers means! all which one cannot name:

His guns, his nets, his lime-twigs, light, and bell:

He creeps, he goes, he stands; yea, who can tell

Of all his postures? Yet there’s none of these

Will make him master of what fowls he please.

Yea, he must pipe and whistle to catch this,

Yet, if he does so, that bird he will miss.

If that a pearl may in a toad’s head dwell,

And may be found too in an oyster-shell;

If things that promise nothing do contain

What better is than gold; who will disdain,

That have an inkling of it, there to look,

That they may find it? Now, my little book,

(Though void of all these paintings that may make

It with this or the other man to take)

Is not without those things that do excel

What do in brave but empty notions dwell.

{5} ‘Well, yet I am not fully satisfied,

{5} ‘Well, yet I am not fully satisfied,

That this your book will stand, when soundly tried.’

Why, what’s the matter? ‘It is dark.’ What though?

‘But it is feigned.’ What of that? I trow?

Some men, by feigned words, as dark as mine,

Make truth to spangle and its rays to shine.

‘But they want solidness.’ Speak, man, thy mind.

‘They drown the weak; metaphors make us blind.’

Solidity, indeed, becomes the pen

Of him that writeth things divine to men;

But must I needs want solidness, because

By metaphors I speak? Were not God’s laws,

His gospel laws, in olden times held forth

By types, shadows, and metaphors? Yet loth

Will any sober man be to find fault

With them, lest he be found for to assault

The highest wisdom. No, he rather stoops,

And seeks to find out what by pins and loops,

By calves and sheep, by heifers and by rams,

By birds and herbs, and by the blood of lambs,

God speaketh to him; and happy is he

That finds the light and grace that in them be.

{6} Be not too forward, therefore, to conclude

{6} Be not too forward, therefore, to conclude

That I want solidness–that I am rude;

All things solid in show not solid be;

All things in parables despise not we;

Lest things most hurtful lightly we receive,

And things that good are, of our souls bereave.

My dark and cloudy words, they do but hold

The truth, as cabinets enclose the gold.

The prophets used much by metaphors

To set forth truth; yea, who so considers Christ,

his apostles too, shall plainly see,

That truths to this day in such mantles be.

Am I afraid to say, that holy writ,

Which for its style and phrase puts down all wit,

Is everywhere so full of all these things–

Dark figures, allegories? Yet there springs

From that same book that lustre, and those rays

Of light, that turn our darkest nights to days.

{7} Come, let my carper to his life now look,

{7} Come, let my carper to his life now look,

And find there darker lines than in my book

He findeth any; yea, and let him know,

That in his best things there are worse lines too.

May we but stand before impartial men,

To his poor one I dare adventure ten,

That they will take my meaning in these lines

Far better than his lies in silver shrines.

Come, truth, although in swaddling clouts, I find,

Informs the judgement, rectifies the mind;

Pleases the understanding, makes the will

Submit; the memory too it doth fill

With what doth our imaginations please;

Likewise it tends our troubles to appease.

Sound words, I know, Timothy is to use,

And old wives’ fables he is to refuse;

But yet grave Paul him nowhere did forbid

The use of parables; in which lay hid

That gold, those pearls, and precious stones that were

Worth digging for, and that with greatest care.

Let me add one word more. O man of God,

Art thou offended? Dost thou wish I had

Put forth my matter in another dress?

Or, that I had in things been more express?

Three things let me propound; then I submit

To those that are my betters, as is fit.

{8} 1. I find not that I am denied the use

{8} 1. I find not that I am denied the use

Of this my method, so I no abuse

Put on the words, things, readers; or be rude

In handling figure or similitude,

In application; but, all that I may,

Seek the advance of truth this or that way

Denied, did I say? Nay, I have leave

(Example too, and that from them that have

God better pleased, by their words or ways,

Than any man that breatheth now-a-days)

Thus to express my mind, thus to declare

Things unto thee that excellentest are.

2. I find that men (as high as trees) will write

Dialogue-wise; yet no man doth them slight

For writing so: indeed, if they abuse

Truth, cursed be they, and the craft they use

To that intent; but yet let truth be free

To make her sallies upon thee and me,

Which way it pleases God; for who knows how,

Better than he that taught us first to plough,

To guide our mind and pens for his design?

And he makes base things usher in divine.

3. I find that holy writ in many places

Hath semblance with this method, where the cases

Do call for one thing, to set forth another;

Use it I may, then, and yet nothing smother

Truth’s golden beams: nay, by this method may

Make it cast forth its rays as light as day.

And now before I do put up my pen,

I’ll shew the profit of my book, and then

Commit both thee and it unto that Hand

That pulls the strong down, and makes weak ones stand.

This book it chalketh out before thine eyes

The man that seeks the everlasting prize;

It shews you whence he comes, whither he goes;

What he leaves undone, also what he does;

It also shows you how he runs and runs,

Till he unto the gate of glory comes.

{9} It shows, too, who set out for life amain,

{9} It shows, too, who set out for life amain,

As if the lasting crown they would obtain;

Here also you may see the reason why

They lose their labour, and like fools do die.

This book will make a traveller of thee,

If by its counsel thou wilt ruled be;

It will direct thee to the Holy Land,

If thou wilt its directions understand:

Yea, it will make the slothful active be;

The blind also delightful things to see.

Art thou for something rare and profitable?

Wouldest thou see a truth within a fable?

Art thou forgetful? Wouldest thou remember

From New-Year’s day to the last of December?

Then read my fancies; they will stick like burs,

And may be, to the helpless, comforters.

This book is writ in such a dialect

As may the minds of listless men affect:

It seems a novelty, and yet contains

Nothing but sound and honest gospel strains.

Wouldst thou divert thyself from melancholy?

Wouldst thou be pleasant, yet be far from folly?

Wouldst thou read riddles, and their explanation?

Or else be drowned in thy contemplation?

Dost thou love picking meat? Or wouldst thou see

A man in the clouds, and hear him speak to thee?

Wouldst thou be in a dream, and yet not sleep?

Or wouldst thou in a moment laugh and weep?

Wouldest thou lose thyself and catch no harm,

And find thyself again without a charm?

Wouldst read thyself, and read thou knowest not what,

And yet know whether thou art blest or not,

By reading the same lines? Oh, then come hither,

And lay my book, thy head, and heart together.

When I think of it, in reflecting upon a lecture for students, I am writing a blog post about marginal notes I wrote next to a letter J.R.R. Tolkien wrote to a Lord of the Rings fan, which I found in Christopher Tolkien’s endnote to an author’s note his father wrote to an inserted episode from the 12-volume History of Middle-earth, which is the Legendarium, that is both the foundation of and the prequel to the published story, The Lord of the Rings.

When I think of it, in reflecting upon a lecture for students, I am writing a blog post about marginal notes I wrote next to a letter J.R.R. Tolkien wrote to a Lord of the Rings fan, which I found in Christopher Tolkien’s endnote to an author’s note his father wrote to an inserted episode from the 12-volume History of Middle-earth, which is the Legendarium, that is both the foundation of and the prequel to the published story, The Lord of the Rings.

Though I probably had an advantage going into the book, like Huck Finn I thought there were some tough things in it. There are pages of doctrinal discussions, where the allegorical characters are splitting hairs over issues that even I—who have studied evangelical theology—can’t see the significance of the distinctions.

Though I probably had an advantage going into the book, like Huck Finn I thought there were some tough things in it. There are pages of doctrinal discussions, where the allegorical characters are splitting hairs over issues that even I—who have studied evangelical theology—can’t see the significance of the distinctions.