As I have been chest-deep in academic works about C.S. Lewis and at least knee-deep in the same kinds of J.R.R. Tolkien books and articles, I conceived of a thought experiment. Without even glancing at my bookshelf, I can name a dozen essential scholarly volumes treating Lewis’ thought, writing, and impact, and some other creative, beautiful, and transformational projects. However, there is just something that invites Tolkien scholarship that is a step above in quality–both in individual examples and in the weight of the work as a whole.

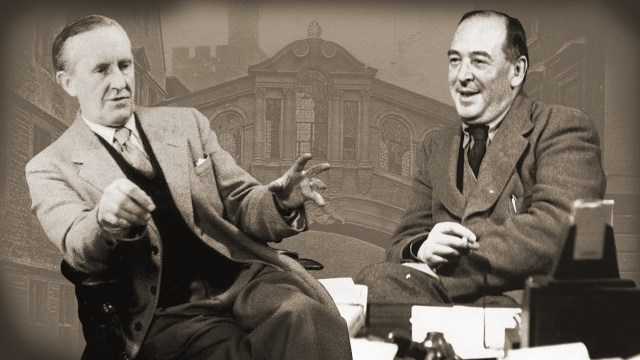

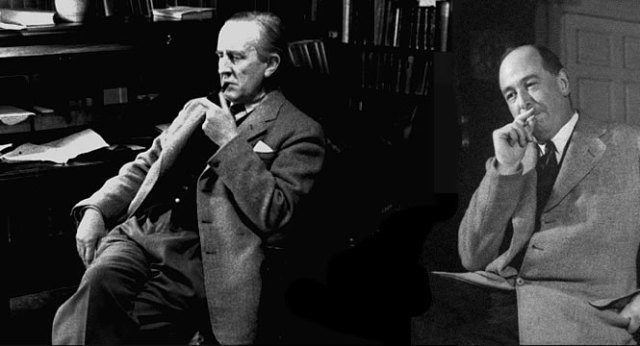

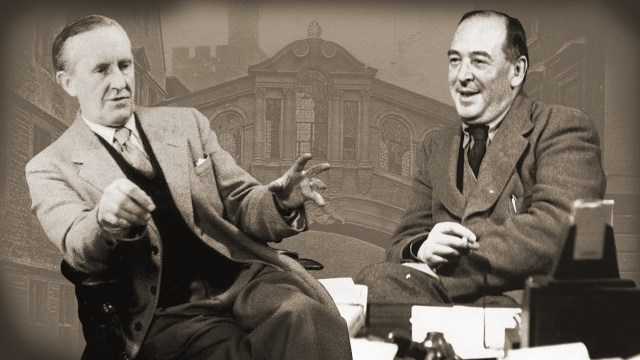

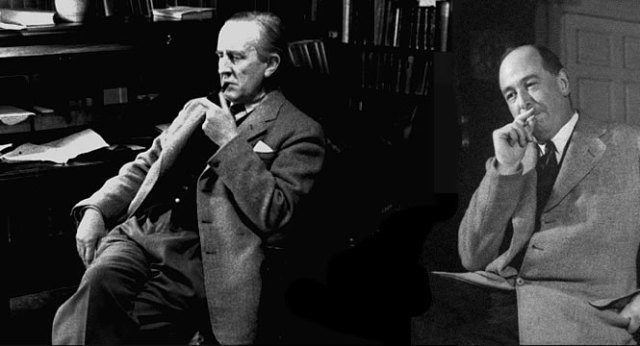

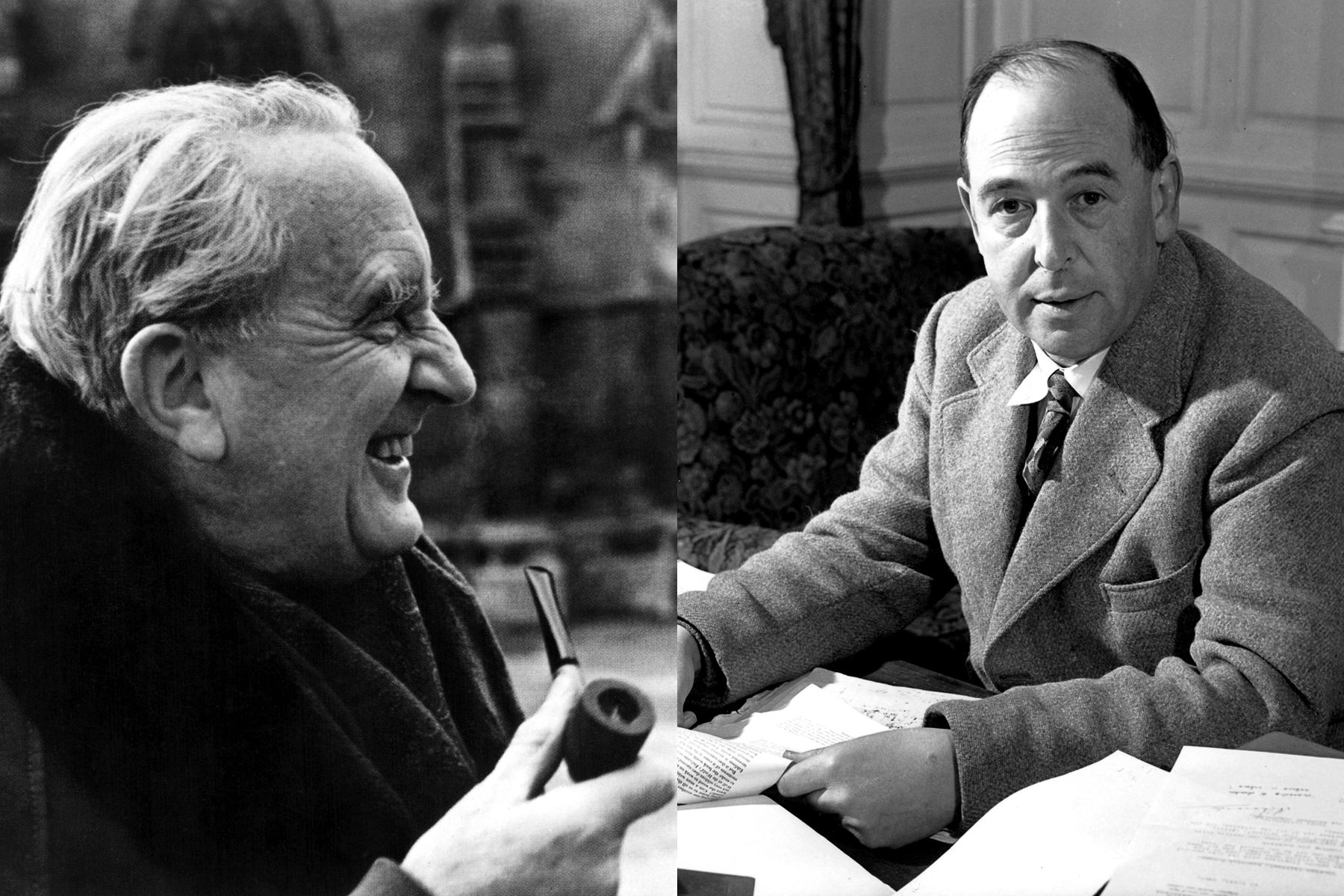

Thus, as a thought experiment, I began a series where I consider factors that could explain a difference, if there is one. My goal wasn’t to set Lewis scholarship as a whole next to Tolkien scholarship, or to create a thunder dome atmosphere where I set scholarly works against each other–though some of that happened as I thought and wrote and engaged with others. In Part 1 of this series entitled, “Why is Tolkien Scholarship Stronger than Lewis Scholarship?,” I talked about four moments in Tolkien readership that resulted in bursts of creative scholarly energy, including the early audiences of Tolkien and Lewis readers, Tolkien and Lewis as literary scholars, the fight for “literary” recognition, and the impact of Peter Jackson’s adaptations for inspiring scholarship. In Part 2, I took the daring approach of comparing and contrasting the work of Lewis and Tolkien. While Lewis excels in a playfulness of genre, quick output, and a broad range of topics in his work, Tolkien was a master of literary and imaginative depth. There is a factor in Lewis scholarship that I call the “Piggyback” effect, where journalists and scholars mistake Lewis’ accessibility for a lack of depth, but there is also the internal reality that Tolkien produced an epic, while Lewis wrote fairy tales and romances.

Of the internal, literary reasons I provide in JRRT vs. CSL Part 2, I think there is a good case to be made about why Tolkien scholarship might invite more depth as it mirrors the depth of its master. But a reason is not a necessity–and in terms of critical approach, literary care, or the adventurous nature of the work, it cannot explain why the culture of Tolkien scholarship has simply been more effective. In Part 3, I develop thoughts from the first two articles by turning to other factors, such as the tools and techniques that Lewis and Tolkien scholars are comfortable in using in their work.

This series of articles is simply here to create a start to the conversation–though I hope to inspire Lewis scholars to dig in and take greater risks. Feel free to critique my reasons or enhance my understanding of Inklings studies with your own insights. Use the comment section or social media to challenge me or develop an idea further. If you want to write an essay in response proving me wrong or right, and if you can write it well enough, I’ll even give you space here to publish it. I think someone is taking me up on this for next week. And I will conclude when this conversation is done with some lessons learned.

8. Other Features of the Field: Christopher Tolkien vs. Walter Hooper

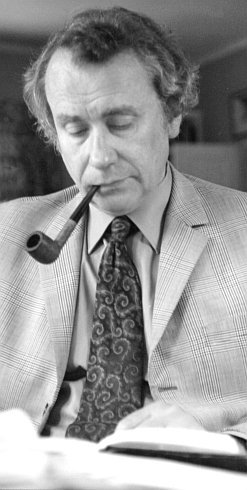

Among the other pieces of news in 2020, it was that year that saw the passing of both Christopher Tolkien–whom I called the “Curator of Middle-earth“–and Walter Hooper, one-time literary secretary and lifelong editor of Lewis’ works.

Among the other pieces of news in 2020, it was that year that saw the passing of both Christopher Tolkien–whom I called the “Curator of Middle-earth“–and Walter Hooper, one-time literary secretary and lifelong editor of Lewis’ works.

There is no doubt that Christopher Tolkien was an irreplaceable feature in Tolkien studies. With the help of others, he brought together a readable version of The Silmarillion before going on to edit the 12-volume History of Middle-earth, as well as a number of other highly edited and prefaced archival publications. Christopher Tolkien focussed so heavily on giving us as many literary, historical, and linguistic layers as possible in the legendarium that he has succeeded in moving The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings from the bedroom shelf to the study (though my paperback copies are still in the bedroom, of course!). It was scholarship that bred scholarship, modelling good practices (many that he had to make up as he went along) while giving ample space for future readers and researchers to come along after him.

While Christopher Tolkien naturally took up his father’s unfinished work, Lewis’ literary estate was in a far different condition when the Narnian died a decade earlier in 1963. Within a half-decade of Lewis’ life, it was clear that there was not a natural successor to Lewis in his family–either of Lewis’ stepsons or his brother, Warren–or his closest friends. Warren gave it a strong beginning with his collection of letters and an attempt at a biography. However, he lacked various capacities for continuing the work. Owen Barfield could very well have curated Lewis’ materials and did a great deal over the decades, but he was beginning a renewed career as a lecturer and public thinker and he excelled in matters other than archival research. Through the decade after Lewis’ death, a role evolved for Walter Hooper to edit Lewis materials, bring poems, letters, stories, and essays together over the next four decades.

Without offering a critique of Hooper’s work, it is no surprise that he naturally reflected Lewis’ diversity of writing in his approach to curating Lewis materials. Hooper gathered letters and poems and short pieces from locations far and wide, and then published them in thematically linked or comprehensive collections. There are a few archival pieces, but unlike Tolkien, most of this material came from magazine indices and collected volumes. Lewis published many of his poems pseudonymously, so there was a bit of trick to the trade. But the overall result reflects Lewis’ own approach to writing: eclectic collections that are thematically linked but could feel distant from the whole. The Weight of Glory is quite different from either God in the Dock or Collected Poems.

Without offering a critique of Hooper’s work, it is no surprise that he naturally reflected Lewis’ diversity of writing in his approach to curating Lewis materials. Hooper gathered letters and poems and short pieces from locations far and wide, and then published them in thematically linked or comprehensive collections. There are a few archival pieces, but unlike Tolkien, most of this material came from magazine indices and collected volumes. Lewis published many of his poems pseudonymously, so there was a bit of trick to the trade. But the overall result reflects Lewis’ own approach to writing: eclectic collections that are thematically linked but could feel distant from the whole. The Weight of Glory is quite different from either God in the Dock or Collected Poems.

And then there is what I argue is Hooper’s most important contribution: the Collected Letters. What a profound resource these letters are–and a personal encouragement in my own writing and faith. While we have some of Tolkien’s letters–many of the more important ones–it is a project that was not at the centre of Christopher Tolkien’s skillset or vision for his father’s legacy.

Ultimately, then, Lewis and Tolkien scholarship followed the resources that were available to them. Oversimplifying the matter, Tolkien scholars followed the material into greater and greater depth, while Lewis scholars followed him out into various areas of study. These are not really “better” and “worse” categories–and I believe that Lewis and Tolkien scholars are equally adept at biographical criticism–but could be a factor in the difference between the scholarship.

9. The Bugbear of Literary Theory

9. The Bugbear of Literary Theory

In my first post in this series, I invited readers to look at academic book catalogues or award finalists and compare Lewis and Tolkien scholarship. One trend is clear in three important Tolkien books from Palgrave MacMillan:

- Dimitra Fimi, Tolkien, Race, and Cultural History: From Fairies to Hobbits (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), Mythopoeic Award winner in Inklings Studies

- Jane Chance, Tolkien, Self and Other: “This Queer Creature” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), Mythopoeic Award nominee in Inklings Studies

- C. Vaccaro and Y. Kisor, eds, Tolkien and Alterity (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017)

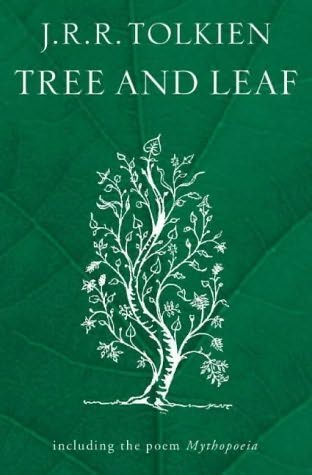

Each of these strong volumes represents theoretical approaches to literary criticism in this generation. There are many great Tolkien volumes that are not driven by literary theory particular to the last century, such as (for the most part) Amy Amendt-Raduege’s 2020 Inklings Studies award-winning volume, “The Sweet and the Bitter”: Death and Dying in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (The Kent State University Press, 2018). However, with exceptional strength in linguistic theory and medieval studies, Tolkien scholarship is often able to walk with literary theory in fruitful ways.

Without a doubt, I have discovered a real resistance in many strands of Lewis scholarship to using literary theoretical tools. That there is a broad and energetic conversation about “Queering Tolkien” is telling: there really isn’t anything like that in Lewis studies, though I think Lewis’ fiction invites such a reading. Lewis’ work begs for a discussion on “alterity”–or “the taste for the other” in Lewis’ own words. What can linguistic theory, in-depth political science questions, or speculative world-building scholarship teach us about Lewis’ fiction? We don’t know–or don’t know fully–because of an anxiety in the field about literary theory.

Without a doubt, I have discovered a real resistance in many strands of Lewis scholarship to using literary theoretical tools. That there is a broad and energetic conversation about “Queering Tolkien” is telling: there really isn’t anything like that in Lewis studies, though I think Lewis’ fiction invites such a reading. Lewis’ work begs for a discussion on “alterity”–or “the taste for the other” in Lewis’ own words. What can linguistic theory, in-depth political science questions, or speculative world-building scholarship teach us about Lewis’ fiction? We don’t know–or don’t know fully–because of an anxiety in the field about literary theory.

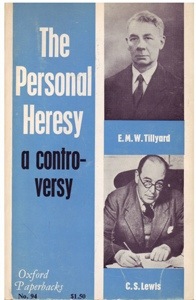

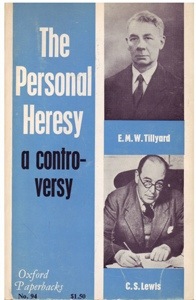

I think this resistance to lit theory comes from four main points of resistance, I think: 1) following Lewis in resisting certain kinds of reading approaches (like psychological approaches or the conversation in The Personal Heresy that actually helped stimulate the “New Criticism” theory movement); 2) a conservative resistance to identity studies among some Lewis scholars; 3) the elitist nature of the literary theory conversation itself; and 4) theoretical conversations about Lewis’ work that have not always read Lewis well or that aren’t evidentially based.

However, I think it is a missed opportunity if we follow this rule of thumb: literary theory is only as good as the readings it produces. A lot of terrible work in psychological criticism comes from the fact that the critics were not great readers. Gender and feminist critics of Lewis–and they abound–have not always read carefully in their haste to bring up concerns or save Lewis from criticism.

However, I think it is a missed opportunity if we follow this rule of thumb: literary theory is only as good as the readings it produces. A lot of terrible work in psychological criticism comes from the fact that the critics were not great readers. Gender and feminist critics of Lewis–and they abound–have not always read carefully in their haste to bring up concerns or save Lewis from criticism.

Frederick Crews’ The Perplex and Postmodern Pooh are pretty great volumes for showing the silliness that tempts some “cutting-edge” literary theorists. But these books also show the potential–a potential worked out in some daring scholars. A great case is Monika B. Hilder’s Mythopoeic Award-nominated C.S. Lewis and gender series, consisting of The Feminine Ethos in C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia (Peter Lang, 2012); The Gender Dance: Ironic Subversion in C.S. Lewis’s Cosmic Trilogy (Peter Lang, 2013); and Surprised by the Feminine: A Rereading of C.S. Lewis and Gender (Peter Lang, 2013). This is solid, engaging work that invites me more deeply into Lewis’ writings. I hope that others look for opportunities to expand their literary toolkit in the years ahead.

10. Literary Societies

My first academic paper in Lewis studies was at the C.S. Lewis and Friends Colloquium at Taylor University, co-sponsored by the C.S. Lewis and Inklings Society. It was a brilliant conference, and I found myself drawn into a world of great reading and writing. In 2018, I spoke at the Oxford C.S. Lewis Society, a society approaching four decades of scholarship and conversation. These are two great societies, and I hope to one day get to the The New York C.S. Lewis Society, founded in 1969, six years after Lewis passed away. These groups and a dozen others have their own niche, producing and giving space to scholarship and popular writing in various kinds of modes. I have nothing but good will for these folks who have taught me so much.

My first academic paper in Lewis studies was at the C.S. Lewis and Friends Colloquium at Taylor University, co-sponsored by the C.S. Lewis and Inklings Society. It was a brilliant conference, and I found myself drawn into a world of great reading and writing. In 2018, I spoke at the Oxford C.S. Lewis Society, a society approaching four decades of scholarship and conversation. These are two great societies, and I hope to one day get to the The New York C.S. Lewis Society, founded in 1969, six years after Lewis passed away. These groups and a dozen others have their own niche, producing and giving space to scholarship and popular writing in various kinds of modes. I have nothing but good will for these folks who have taught me so much.

However, none of these societies has the kind of energy and productivity of the Tolkien Society. The Oxford Lewis society produces occasional volumes and has a partnership of some kind with The Journal of Inklings Studies. The NY CSL Society’s journal is a great history of Lewis reading for more than 50 years with sparks of brilliance and good solid work. But before Tolkien had passed away, the Tolkien Society was already on the move. Today, programs like Oxonmoot, the Birthday Toast, Tolkien Reading Day, and various meetings create a unique global readerly and scholarly energy. More than that, though, various scholarly journals and publications combine with The Tolkien Society Awards to encourage scholarship in a way that Lewis societies cannot match. The Mythopoeic Society does this well for both Lewis and Tolkien, but the Tolkien Society with its local smials have energized rooted scholarship for decades.

However, none of these societies has the kind of energy and productivity of the Tolkien Society. The Oxford Lewis society produces occasional volumes and has a partnership of some kind with The Journal of Inklings Studies. The NY CSL Society’s journal is a great history of Lewis reading for more than 50 years with sparks of brilliance and good solid work. But before Tolkien had passed away, the Tolkien Society was already on the move. Today, programs like Oxonmoot, the Birthday Toast, Tolkien Reading Day, and various meetings create a unique global readerly and scholarly energy. More than that, though, various scholarly journals and publications combine with The Tolkien Society Awards to encourage scholarship in a way that Lewis societies cannot match. The Mythopoeic Society does this well for both Lewis and Tolkien, but the Tolkien Society with its local smials have energized rooted scholarship for decades.

11. The Beautiful Problem of Scholarly Friends

It is odd, perhaps, to end with a positive-negative, but it is worth doing. Part of the story I have told of my journey into Lewis studies has been the support and encouragement of other scholars. There have been times that the community has split, such as the “Lindskoog Affair.” But part of the reason that rift in Lewis scholarship was so painful was because there has always been a desire to engender fellowship among Lewis scholars. I think this comes from a desire to reflect the Inklings’ ability to inspire some of the more important books and stories of the 20th-century from within a small collective. But we also must admit that there is some sense in which Lewis scholarship is endeavouring to be Christian scholarship and fellowship in a way that Tolkien scholarship as a whole is not.

It is odd, perhaps, to end with a positive-negative, but it is worth doing. Part of the story I have told of my journey into Lewis studies has been the support and encouragement of other scholars. There have been times that the community has split, such as the “Lindskoog Affair.” But part of the reason that rift in Lewis scholarship was so painful was because there has always been a desire to engender fellowship among Lewis scholars. I think this comes from a desire to reflect the Inklings’ ability to inspire some of the more important books and stories of the 20th-century from within a small collective. But we also must admit that there is some sense in which Lewis scholarship is endeavouring to be Christian scholarship and fellowship in a way that Tolkien scholarship as a whole is not.

There is a lot that is beautiful about this community of scholarly Lewis friends, but there is a downside. Pick up a volume of one of the Lewis scholarly journals–I just picked up the 2020 Sehnsucht, a critical Lewis scholarship journal–and you will find warm, glowing reviews nearly across the board. They are well written and respectful, offering a point or two of rebuttal or correction, but they are rarely reviews that really challenge the work at its core or in detail. When they do, it is sometimes because the author under review has been tempted to co-opt or misinterpret Lewis–so the reviewer is operating on an instinct to protect Lewis.

I am not saying that these are bad critics, that they missed things in the books under review in this recent journal, or that protecting an author is totally bad. My review writing is usually pretty glowing, I admit. I want to read good books I want collaboration–and this same volume of Sehnsucht has a correction by Joe Ricke of something that Charlie Starr and I did together. It is a great example of how a good challenge is an opportunity for growth. But there is little in Lewis scholarship and almost nothing in the reviews like the Lewis-Barfield belief that “opposition is true friendship.” The iron-sharpens-iron approach is just too rare in Lewis studies.

I am not saying that these are bad critics, that they missed things in the books under review in this recent journal, or that protecting an author is totally bad. My review writing is usually pretty glowing, I admit. I want to read good books I want collaboration–and this same volume of Sehnsucht has a correction by Joe Ricke of something that Charlie Starr and I did together. It is a great example of how a good challenge is an opportunity for growth. But there is little in Lewis scholarship and almost nothing in the reviews like the Lewis-Barfield belief that “opposition is true friendship.” The iron-sharpens-iron approach is just too rare in Lewis studies.

And frankly, for me anyway, oppositional friendship is exhausting. I don’t want to spend time reviewing bad books, and I don’t want to critique my friends publicly. Indeed, if I had enemies–or even a nemesis–I wouldn’t want to critique them either! I just completed a largely negative review for an academic journal and wish that I had never heard of the book rather than have to spend my time that way. Indeed, I have mostly given up academic reviewing because I cannot seem to balance the negative and positive well. And as someone who does all this for free, I can make that choice.

Moreover, when I have endeavoured to make this sort of public challenge–as I did of Michael Ward’s generative Planet Narnia thesis–some caring scholars reached out to me to make sure that I walked carefully. Many Lewis readers have really invested in the Planet Narnia approach and I might cause some harm to myself or others. Michael Ward himself seemed pleased rather than otherwise to find I was challenging him–though I have not spoken to him since it was published. But there is a whiff of bad faith about those who step out of the fellowship of scholars and challenge too much.

The reader will see that I am naming my weakness here as much as anyone’s, but it is an intriguing problem. I have compensated for this weakness that is also a strength by cultivating scholarly connections in Lewis studies that will, I am afraid, leave me no quarter when I am not at my best.

The reader will see that I am naming my weakness here as much as anyone’s, but it is an intriguing problem. I have compensated for this weakness that is also a strength by cultivating scholarly connections in Lewis studies that will, I am afraid, leave me no quarter when I am not at my best.

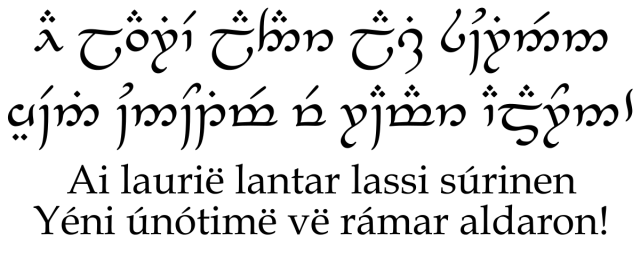

And I want to caution readers that I am saying nothing bad about Tolkien scholars communities. As much as my small forays into the Tolkien studies field have been so positive and encouraging, their dynamic is more critical. Indeed, I have suggested that there such a thing as a Tolkien Expertise Anxiety Syndrome (TEAS). I am certain that whenever I talk about Tolkien in lectures and writing, two Tolkienists are in the back of the room mocking me in Quenya. So it goes! But most of my experiences have been both thoughtful and positive.

12. No More Lewis Studies, Please

Lastly, and just as a brief note, there is an odd phenomenon in Lewis scholarship. Because of a perception of too much published content in the mid-2000s with the release of the Disney Narnian adaptations and the 50th anniversary of Lewis’ death in 2013. There has been some resistance among publishers to take new Lewis studies into their catalogues. This is enhanced, I think, by the piggyback phenomenon I talked about last week, what others call Jacksploitation or “the Lewis industry.” “No more Lewis studies, please” was what I was told just as I began my PhD a few years ago–a pretty discouraging thing to hear as a new scholar!

Lastly, and just as a brief note, there is an odd phenomenon in Lewis scholarship. Because of a perception of too much published content in the mid-2000s with the release of the Disney Narnian adaptations and the 50th anniversary of Lewis’ death in 2013. There has been some resistance among publishers to take new Lewis studies into their catalogues. This is enhanced, I think, by the piggyback phenomenon I talked about last week, what others call Jacksploitation or “the Lewis industry.” “No more Lewis studies, please” was what I was told just as I began my PhD a few years ago–a pretty discouraging thing to hear as a new scholar!

It is true that there is a challenging sales dynamic for in-depth literary studies. In order to make a book or series affordable to a hungry Lewis-reading audience, the book has to be written and designed to meet that smart but not always academically trained readership. It is a delicate balance of research, writing, editing, and book production that challenges scholars and may make some editors hesitant. I know that there are some strong academic Lewis studies books where the scholar has struggled to find a publishing home. But I also know that there are some small- and medium-sized presses wanting to extend their Inklings line–as well as some large presses like Peter Lang or Oxford that will consider a Lewis book of exceptional value.

So I end with a note of hope. Perhaps a publishing industry hesitancy has existed at times, but there is still room for a great book to come along–including yours, perhaps?

I believe in open access scholarship. Because of this, since 2011 I have made A Pilgrim in Narnia free with nearly 1,000 posts on faith, fiction, and fantasy. Please consider sharing my work so others can enjoy it.

Among the other pieces of news in 2020, it was that year that saw the passing of both Christopher Tolkien–whom I called the “

Among the other pieces of news in 2020, it was that year that saw the passing of both Christopher Tolkien–whom I called the “ Without offering a critique of Hooper’s work, it is no surprise that he naturally reflected

Without offering a critique of Hooper’s work, it is no surprise that he naturally reflected  9. The Bugbear of Literary Theory

9. The Bugbear of Literary Theory Without a doubt, I have discovered a real resistance in many strands of Lewis scholarship to using literary theoretical tools. That there is a broad and energetic conversation about “Queering Tolkien” is telling: there really isn’t anything like that in Lewis studies, though I think Lewis’ fiction invites such a reading. Lewis’ work begs for a discussion on “alterity”–or “the taste for the other” in Lewis’ own words. What can linguistic theory, in-depth political science questions, or speculative world-building scholarship teach us about Lewis’ fiction? We don’t know–or don’t know fully–because of an anxiety in the field about literary theory.

Without a doubt, I have discovered a real resistance in many strands of Lewis scholarship to using literary theoretical tools. That there is a broad and energetic conversation about “Queering Tolkien” is telling: there really isn’t anything like that in Lewis studies, though I think Lewis’ fiction invites such a reading. Lewis’ work begs for a discussion on “alterity”–or “the taste for the other” in Lewis’ own words. What can linguistic theory, in-depth political science questions, or speculative world-building scholarship teach us about Lewis’ fiction? We don’t know–or don’t know fully–because of an anxiety in the field about literary theory. However, I think it is a missed opportunity if we follow this rule of thumb: literary theory is only as good as the readings it produces. A lot of terrible work in psychological criticism comes from the fact that the critics were not great readers. Gender and feminist critics of Lewis–and they abound–have not always read carefully in their haste to bring up concerns or save Lewis from criticism.

However, I think it is a missed opportunity if we follow this rule of thumb: literary theory is only as good as the readings it produces. A lot of terrible work in psychological criticism comes from the fact that the critics were not great readers. Gender and feminist critics of Lewis–and they abound–have not always read carefully in their haste to bring up concerns or save Lewis from criticism.

My

My  However, none of these societies has the kind of energy and productivity of the Tolkien Society. The Oxford Lewis society produces occasional volumes and has a partnership of some kind with The Journal of Inklings Studies. The NY CSL Society’s journal is a great history of Lewis reading for more than 50 years with sparks of brilliance and good solid work. But before Tolkien had passed away, the Tolkien Society was already on the move. Today, programs like Oxonmoot, the Birthday Toast, Tolkien Reading Day, and various meetings create a unique global readerly and scholarly energy. More than that, though, various scholarly journals and publications combine with The Tolkien Society Awards to encourage scholarship in a way that Lewis societies cannot match. The Mythopoeic Society does this well for both Lewis and Tolkien, but the Tolkien Society with its local smials have energized rooted scholarship for decades.

However, none of these societies has the kind of energy and productivity of the Tolkien Society. The Oxford Lewis society produces occasional volumes and has a partnership of some kind with The Journal of Inklings Studies. The NY CSL Society’s journal is a great history of Lewis reading for more than 50 years with sparks of brilliance and good solid work. But before Tolkien had passed away, the Tolkien Society was already on the move. Today, programs like Oxonmoot, the Birthday Toast, Tolkien Reading Day, and various meetings create a unique global readerly and scholarly energy. More than that, though, various scholarly journals and publications combine with The Tolkien Society Awards to encourage scholarship in a way that Lewis societies cannot match. The Mythopoeic Society does this well for both Lewis and Tolkien, but the Tolkien Society with its local smials have energized rooted scholarship for decades. It is odd, perhaps, to end with a positive-negative, but it is worth doing. Part of the story I have told of my journey into Lewis studies has been the support and encouragement of other scholars. There have been times that the community has split, such as the “

It is odd, perhaps, to end with a positive-negative, but it is worth doing. Part of the story I have told of my journey into Lewis studies has been the support and encouragement of other scholars. There have been times that the community has split, such as the “ I am not saying that these are bad critics, that they missed things in the books under review in this recent journal, or that protecting an author is totally bad. My

I am not saying that these are bad critics, that they missed things in the books under review in this recent journal, or that protecting an author is totally bad. My  The reader will see that I am naming my weakness here as much as anyone’s, but it is an intriguing problem. I have compensated for this weakness that is also a strength by cultivating scholarly connections in Lewis studies that will, I am afraid, leave me no quarter when I am not at my best.

The reader will see that I am naming my weakness here as much as anyone’s, but it is an intriguing problem. I have compensated for this weakness that is also a strength by cultivating scholarly connections in Lewis studies that will, I am afraid, leave me no quarter when I am not at my best. Lastly, and just as a brief note, there is an odd phenomenon in Lewis scholarship. Because of a perception of too much published content in the mid-2000s with the release of the Disney Narnian adaptations and the 50th anniversary of Lewis’ death in 2013. There has been some resistance among publishers to take new Lewis studies into their catalogues. This is enhanced, I think, by the piggyback phenomenon I talked about

Lastly, and just as a brief note, there is an odd phenomenon in Lewis scholarship. Because of a perception of too much published content in the mid-2000s with the release of the Disney Narnian adaptations and the 50th anniversary of Lewis’ death in 2013. There has been some resistance among publishers to take new Lewis studies into their catalogues. This is enhanced, I think, by the piggyback phenomenon I talked about

So my question is this: Why is does the culture of Tolkien scholarship invite a critical depth and quality of adventurous scholarship that is found far more rarely in Lewis scholarship?

So my question is this: Why is does the culture of Tolkien scholarship invite a critical depth and quality of adventurous scholarship that is found far more rarely in Lewis scholarship?

There are different ways to think about depth and breadth. I

There are different ways to think about depth and breadth. I  Lewis is not like

Lewis is not like

The “Piggyback Effect” is a particularly nefarious version of the previous conversation about missing Lewis’ depth because the breadth seems insurmountable. Particularly after the release of the Narnia films, there has been a tendency for journalists, writers, and scholars to pick up Lewis’ story and run with it. Scholars in other fields, as well, sometimes feel free to take up Lewis without necessarily committing to becoming comprehensive experts in his thought–or even aware of his deeper resonances. Whether cherry-picking from Lewis’ best and worst bits, or simply using the energy of a public conversation to sell books or to capitalize on media attention, there is an assumption that scholars and commentators can simply walk in, quote a bit of Lewis, and feel like they have captured the whole.

The “Piggyback Effect” is a particularly nefarious version of the previous conversation about missing Lewis’ depth because the breadth seems insurmountable. Particularly after the release of the Narnia films, there has been a tendency for journalists, writers, and scholars to pick up Lewis’ story and run with it. Scholars in other fields, as well, sometimes feel free to take up Lewis without necessarily committing to becoming comprehensive experts in his thought–or even aware of his deeper resonances. Whether cherry-picking from Lewis’ best and worst bits, or simply using the energy of a public conversation to sell books or to capitalize on media attention, there is an assumption that scholars and commentators can simply walk in, quote a bit of Lewis, and feel like they have captured the whole.

In the end, when it comes to literary scholarship, it is difficult to compare Lewis’ fiction with Tolkien’s.

In the end, when it comes to literary scholarship, it is difficult to compare Lewis’ fiction with Tolkien’s. And then there is

And then there is