As part of my “Blogging the Hugos” series, I have just finished Black Sun by Rebecca Roanhorse. Normally as I am reading a book, a theme or image or idea emerges that gives me a chance to write a review that goes beyond “here’s the story, the good, and the bad.” I do have a lot of feelings about this complex and beautifully crafted novel. I am astonished, I think—“stunned” (in the medieval sense of the word) to silence by the images and characters and world-building. Or maybe I am “thunderstruck” (in the Latin sense of the word), wary of the storm’s approach, the threat in Thor’s din, though it is the flood of story and lightning flash of idea that should be my real concern.

As part of my “Blogging the Hugos” series, I have just finished Black Sun by Rebecca Roanhorse. Normally as I am reading a book, a theme or image or idea emerges that gives me a chance to write a review that goes beyond “here’s the story, the good, and the bad.” I do have a lot of feelings about this complex and beautifully crafted novel. I am astonished, I think—“stunned” (in the medieval sense of the word) to silence by the images and characters and world-building. Or maybe I am “thunderstruck” (in the Latin sense of the word), wary of the storm’s approach, the threat in Thor’s din, though it is the flood of story and lightning flash of idea that should be my real concern.

Whatever the case, I am unsettled, and realize that I am unsure what to say about Black Sun, the Hugo-, Nebula-, and Locus-Award nominated first novel by Rebecca Roanhorse, a New Mexico writer of Indigenous and African American descent.

Black Sun is a story of convergence. For more than three centuries, the warring peoples of the Meridian have maintained a tentative peace following a period of fratricidal and tribal bloodshed. To end the wars, clan leaders agree to a suppression of local worship—a limitation of the local gods who were felt to be connected to the rising powers that nearly led to the wasting of their cultures. Superstitions continue, local cults thrive in underground communities, and magic still lives in the hearts of healers, witches, sorcerers, and counsellors. However, public religious power is now in the hands of “the Watchers,” a moderate religious society led by the Sun Priest and various orders in the Celestial Tower at the heart of the mammoth and diverse city of Tova.

Through the years, the clans continue to lead their communities, named for the (somewhat mythical) animals who live with them in kinship, such as the Winged Serpent, the Golden Eagle, Water Strider, and Carrion Crow. Doubtless there are other great clans, as there are other peoples on the edge of our tale, like the mountainous Obregi and the matriarchal Teek. And there are the clanless ones, the gutter trash and outcasts of the “Dry Earth.” Clashes of clan leaders are always possible, but the matrons, patrons, priests, community leaders, and crime bosses share some interest in keeping this tentative peace in Tova and across the Meridian.

Haunting the imagination of this civilization is the “Night of Knives,” a ruthless slaughter a generation earlier, where the Priest of Knives led a holy war against Carrion Crow clan in a desire to drive out the worship of the ancient gods that feel would threaten the peace. It was this act of violence, a tribal cleansing, that has ironically destabilized the peace. Clan members never forget the moment–the horror, the sacrilege, the devastation. A cult has grown up among the peoples, popular and well-armed, waiting for a moment of prophetic alignment to launch their rebellion.

Haunting the imagination of this civilization is the “Night of Knives,” a ruthless slaughter a generation earlier, where the Priest of Knives led a holy war against Carrion Crow clan in a desire to drive out the worship of the ancient gods that feel would threaten the peace. It was this act of violence, a tribal cleansing, that has ironically destabilized the peace. Clan members never forget the moment–the horror, the sacrilege, the devastation. A cult has grown up among the peoples, popular and well-armed, waiting for a moment of prophetic alignment to launch their rebellion.

Within Black Sun is an intricately designed imaginative world, and a cultural moment rife for adventure. Where Roanhorse excels as a storyteller in is the characters that embody (and are embodied by) her world.

This story, the first of the Between Earth and Sky series, introduces several separate character paths that move together towards “Convergence”—a solar eclipse that occurs on winter solstice, creating darkness on the darkest day of the year. Narampa has ascended from the Dry Earth slums to the mantle of the Sun Priest within a class-conscious hierarchy, and must negotiate her political space between factions that seek power and those that desire peace. Okoa has been schooled in the arts of war and peace, and upon his mother’s suspicious death, he must apply his trade to a complex game of statecraft. Serapio, a manifestation of the Crow God, has completed his training in magic, mysticism, and martial arts, and is moving toward Tova for his predestined moment. And Xiala, a Teek woman made up of myth and a sailor’s sense of danger, finds herself alienated from home and drawn to Tova as an unwilling witness to the Black Sun.

I have had since childhood a fascination with Mesoamerican cultures, particularly the Aztecs and, later, the Mayans, so Roanhorse’s reliance on Mesoamerican indigenous myth and legend at the heart of her fiction was deeply attractive to me. But it was actually the way that Audible curated Black Sun that convinced me to purchase the audiobook—long before I decided to do a series on this year’s Hugo-nominated novels.

I have had since childhood a fascination with Mesoamerican cultures, particularly the Aztecs and, later, the Mayans, so Roanhorse’s reliance on Mesoamerican indigenous myth and legend at the heart of her fiction was deeply attractive to me. But it was actually the way that Audible curated Black Sun that convinced me to purchase the audiobook—long before I decided to do a series on this year’s Hugo-nominated novels.

Black Sun popped upon on my suggested reading list, and was featured strongly as an Editor’s choice book. I happened to click through, and began listening to a short interview with the author. I loved that the audiobook producers had consulted with the author and that it was an unabridged cast production performed by voice actors who are indigenous or people of colour (starring Cara Gee, Nicole Lewis, Kaipo Schwab, Shaun Taylor-Corbett). But what caught me—what made me want to read the story—was Roanhorse’s drive to write:

“I have always wanted to write a big, sprawling epic fantasy. These were really my favourite books growing up…. My heart is really in … the world-building and the grandeur of epic fantasy.”

That I get, if nothing else.

And the Meridian is a world-builder’s dream. I am envious of what Roanhorse has done to bring together into a living space such dynamic elements as political intrigue, religion and ritual, mythology and legend, language and scripture, invented history, landscape, seascape, and mountain terrain. There, in Roanhorse’s Meridian world, the characters live brightly. They grow both in our imagination and in their own challenges and adventures. Elegantly, and with a deft literary hand, Roanhorse elevates a stock tool of adventure stories—the converging paths—to become the central guiding image and critical plot structure.

And the Meridian is a world-builder’s dream. I am envious of what Roanhorse has done to bring together into a living space such dynamic elements as political intrigue, religion and ritual, mythology and legend, language and scripture, invented history, landscape, seascape, and mountain terrain. There, in Roanhorse’s Meridian world, the characters live brightly. They grow both in our imagination and in their own challenges and adventures. Elegantly, and with a deft literary hand, Roanhorse elevates a stock tool of adventure stories—the converging paths—to become the central guiding image and critical plot structure.

I am astonished at how much is well done in this novel.

But I am also storm wary, disturbed, thunderstruck.

First, this is a very difficult novel in which to orient oneself—at least for me. I read the first chapter a number of times, and could not find my way to understanding it. I finally decided to treat it like a prologue, trusting that I would get there eventually. Ultimately, I turned to the well-produced audiobook to carry me into that world. Returning to the visually disturbing childhood story at the end of the tale made a number of things connect for me, but cannot take away the terror I feel in Serapio’s vision.

Second, I am unsettled by the ending. You have to admire an author that leaves me desperate to read what comes next—and it is perhaps my own disappointment speaking when I say that the second part of the story, Fevered Star, will be not be out until the springtime. In epic fantasy, there is a subtle craft to resolving the opening tale in a way that satisfies the first-time reader and also prepares the character and the world for the trilogy (or a tetradecology, in the case of Wheel of Time). Black Sun feel unresolved, like one thing more was needed.

Second, I am unsettled by the ending. You have to admire an author that leaves me desperate to read what comes next—and it is perhaps my own disappointment speaking when I say that the second part of the story, Fevered Star, will be not be out until the springtime. In epic fantasy, there is a subtle craft to resolving the opening tale in a way that satisfies the first-time reader and also prepares the character and the world for the trilogy (or a tetradecology, in the case of Wheel of Time). Black Sun feel unresolved, like one thing more was needed.

And, third, I am unsettled about the moral vision of the story. This is a story where the author is doing something to us, I think. Epic fantasy is a genre primed for readerly discoveries, and this story never clangs with the discordant misuse of allegory or soapboxism. It is a bit tinny in moments where the author is attempting to challenge a reader’s built-in expectations, but that is perhaps to be expected as Roanhorse is not simply building a world or telling a story but shaping a diction for a new vision for world-building and storytelling. It is a moralistic age, and for the most part Roanhorse does this well.

But, in what is clearly a tale of moral expectation, I am unsettled about where the reader is to discern the measurement of moral value. It would be a mistake, I think, to attempt to align Roanhorse (or the text’s expectation) solely with any one of the main points of view in the novel—especially when considering the contexts into which Roanhorse is sharing her stories.

So I remain unsettled. This complexity of form, lack of resolution, and mercurial moral vision that I know is calling me somewhere … what am I to make of it all?

It may be that Black Sun is a work of genius beyond my imaginative capacity. It would not be the first great work that has passed me by.

It may be that Rebecca Roanhorse, clearly a skilled poet and master world-builder, still has more to learn in crafting epic fantasy.

Or it may be that, given my education and culture and self-curated love of literature, I am primed for certain story virtues—expectation, resolution, and foundation—that indigenous writers have some reason to challenge. Perhaps I should be unsettled. Perhaps astonishment is the right response to such a tale.

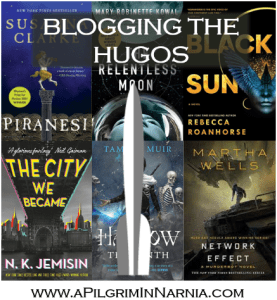

Blogging the Hugos 2021 (Tentative Schedule)

Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Relentless Moon and the Lady Astronaut Universe (11/10/21)

Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Relentless Moon and the Lady Astronaut Universe (11/10/21)- Sarcastabots, The Wall-E Effect, and Finding the Human in Martha Wells’ Network Effect (11/17/21)

- A Time to Listen: Rebecca Roanhorse’s Astonishing Novel Black Sun (11/24/21)

- How N.K. Jemisin Rules The City We Became (12/01/21)

- The Heroic Gideon and Harrowing Features of Living in the Ninth: Tamsyn Muir’s Decaying Necromantic World (12/08/21)

- The Worlds of Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi and Owen Barfield‘s Philosophy (12/15/21)

- The Signum University Hugo Award Best Novel Roundtable (12/18/21)