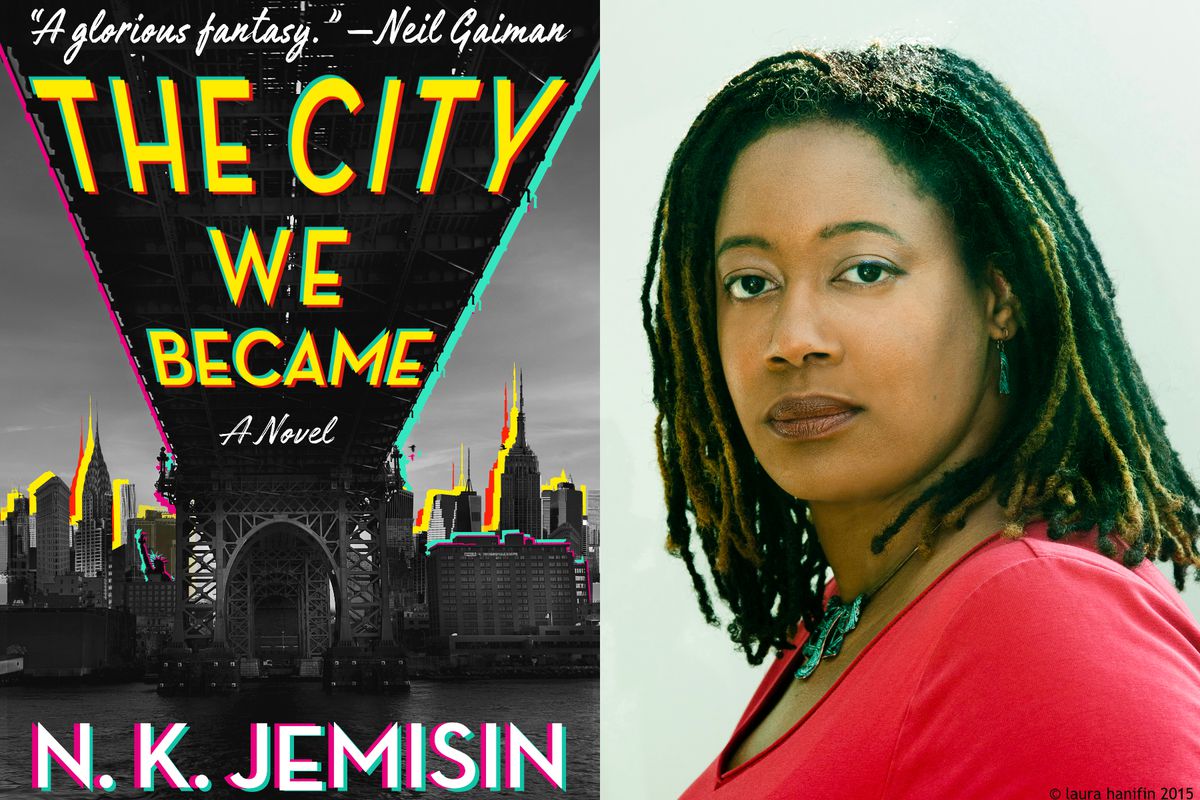

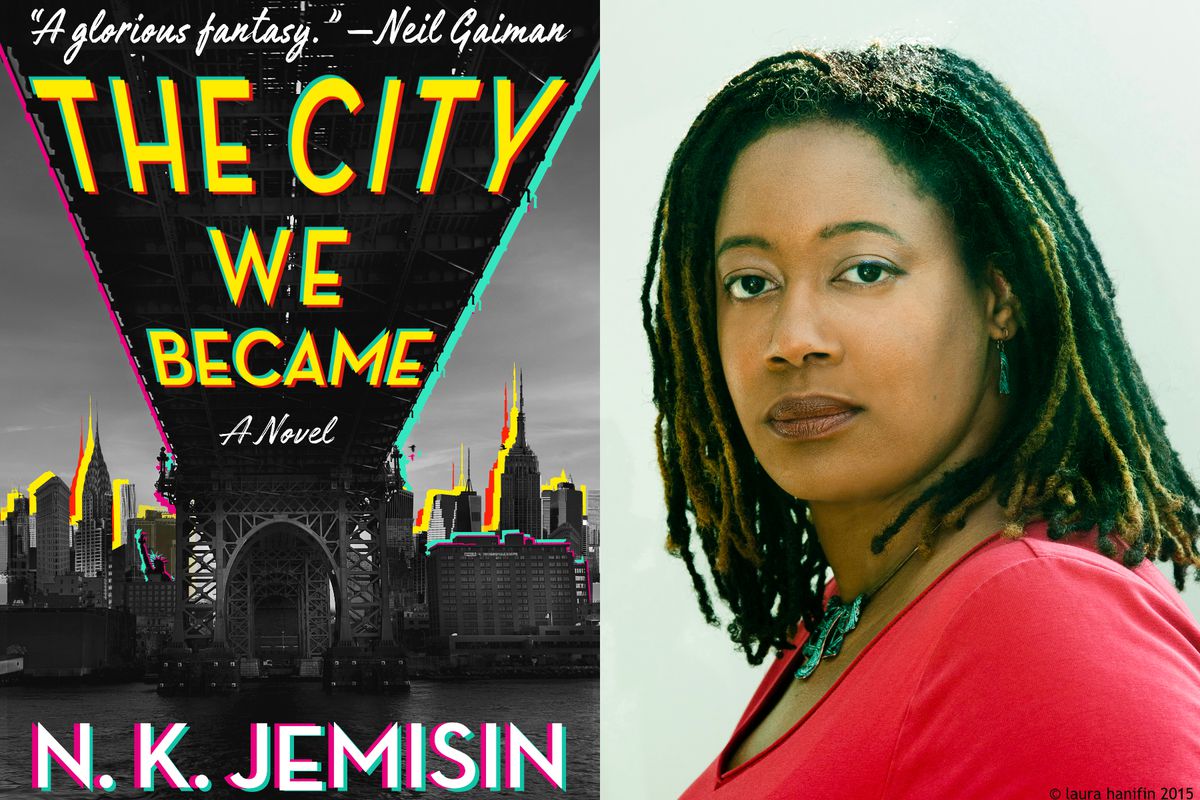

N.K. Jemisin is clearly one of the science fiction greats of the generation. Time will tell if she will stand with the all-time greats, like H.G. Wells, Robert A. Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, Frank Herbert, Ursula K. Le Guin, Philip K. Dick, or Octavia E. Butler. With her triple Hugo Award-winning Broken Earth series—the only author to have an entire trilogy win, the only author to win three years in a row, and one of only five writers who have three or more wins—Jemisin may already be there. Whether or not she is officially part of “Octavia’s Brood”—the dynamic collection of social justice-oriented sf stories by Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown—Jemisin is one of the more prolific of the Black women authors who resonate with Butler’s work, including Tananarive Due, Nalo Hopkinson, Nisi Shawl, and one of my favourites, Nnedi Okorafor.

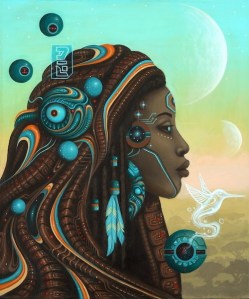

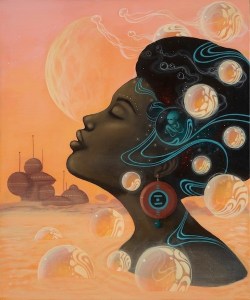

I am definitely an admirer of Jemisin’s work as a world-builder and character-centred prose writer. She combines the imagistic capacity of William Gibson with Ray Bradbury’s experimental tendencies. Then Jemisin, in the tradition of Octavia Butler’s inversive perspective, applies her very own broad and diverse world-building and character-building capabilities to a story of immediacy and cultural relevance. While Jemisin is clearly a lover of story and a great reader, in all of her work there is a unique energy for a new age.

I am definitely an admirer of Jemisin’s work as a world-builder and character-centred prose writer. She combines the imagistic capacity of William Gibson with Ray Bradbury’s experimental tendencies. Then Jemisin, in the tradition of Octavia Butler’s inversive perspective, applies her very own broad and diverse world-building and character-building capabilities to a story of immediacy and cultural relevance. While Jemisin is clearly a lover of story and a great reader, in all of her work there is a unique energy for a new age.

That said, even with all that is fun and thoughtful in the tale, Jemison’s fifth Hugo nomination for best novel, The City We Became, is not a story that resonated with me. The short story “The City Born Great” is brilliant and I love many of the characters and a number of fascinating scenes. In what I describe as an “urban apocalypse” in my description of the novel—you can click here to read that piece—Jemisin goes some distance in filling out the mythological background to that original New York street tale. However, as a moralistic narrative, this novel struggles to find an allegorical diction that allows Jemisin’s literary skills to reach their full potential.

That said, even with all that is fun and thoughtful in the tale, Jemison’s fifth Hugo nomination for best novel, The City We Became, is not a story that resonated with me. The short story “The City Born Great” is brilliant and I love many of the characters and a number of fascinating scenes. In what I describe as an “urban apocalypse” in my description of the novel—you can click here to read that piece—Jemisin goes some distance in filling out the mythological background to that original New York street tale. However, as a moralistic narrative, this novel struggles to find an allegorical diction that allows Jemisin’s literary skills to reach their full potential.

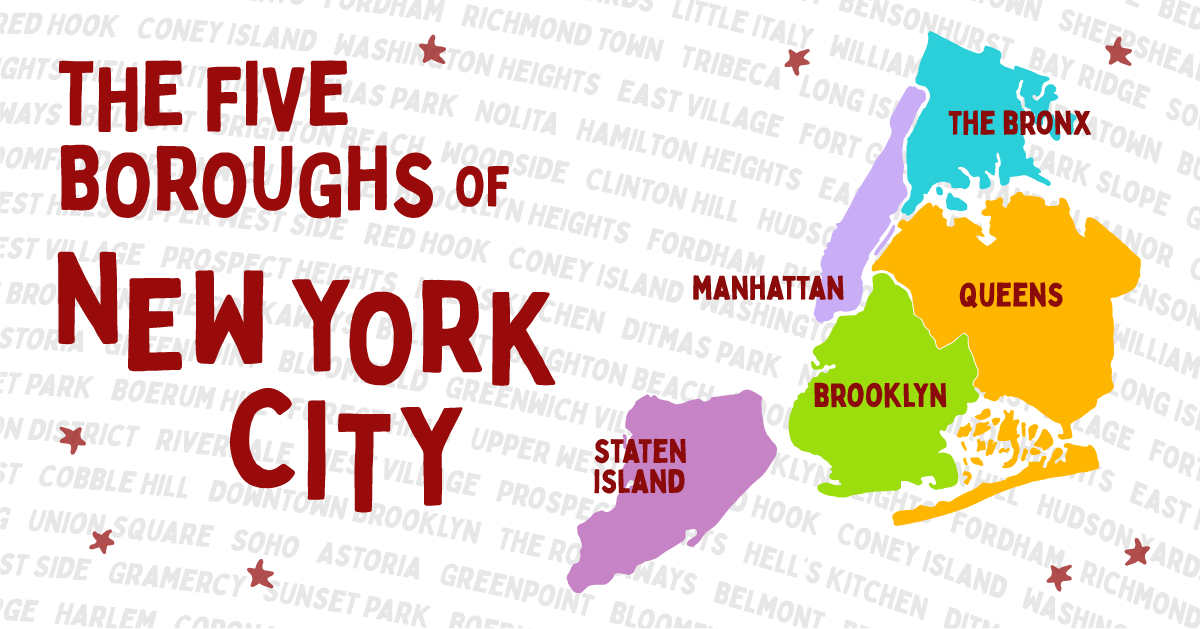

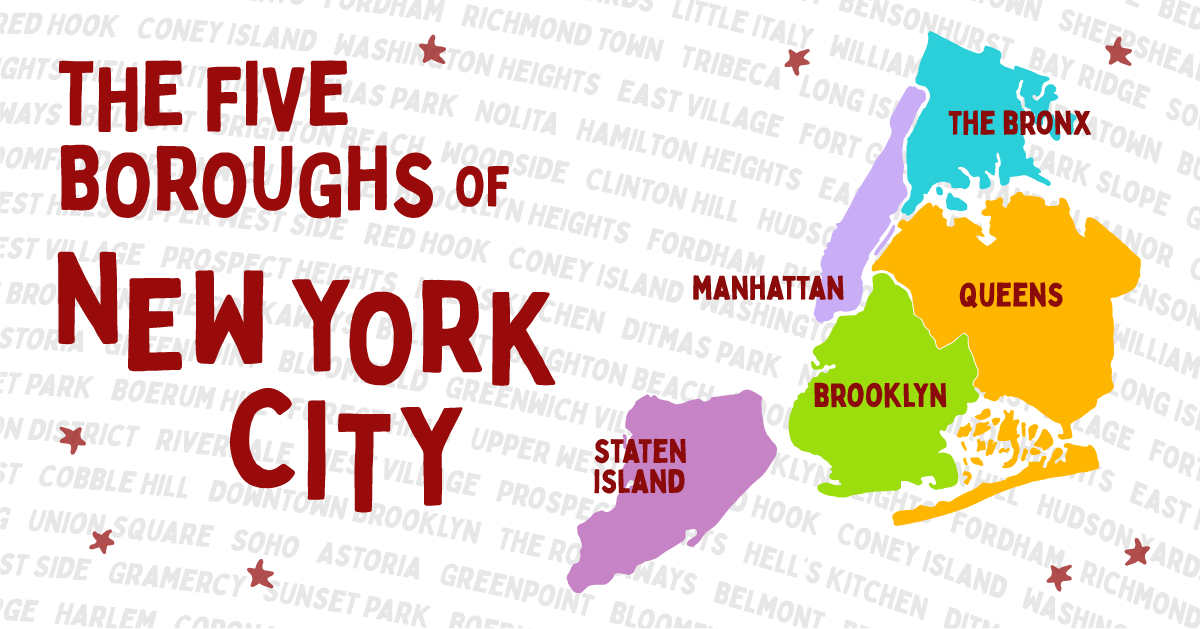

Structurally speaking, Jemisin creates an apocalyptic cosmic battle within an extremely complex speculative universe framework where the world, story, characters, and cosmic battle are all meant to work simultaneously on a number of allegorical layers. This complex allegory, while having moments of imaginative brilliance, turns out to be far too unruly for this urban myth. Furthermore, where these various elements of allegory, symbol, myth, and urban identity come together, there is an essential contradiction in the moral foundation of The City We Became and the way that Jemisin has chosen to draw the vile, villainous, vicious, vapid, and valueless characters, the bad guys. Whether by accident or intention, there are a number of New Yorkers who aid the alien Foe who threatens the city of New York as a newborn entity. Thus, they are also aiding the Foe, who seeks to destroy the allies of New York, the good guys. These enigmatic end-times superheroes are the avatars of New York’s boroughs who draw together to use their unique and authentically New York skills to fight against evil, destruction, division, bigotry, and other things that destroy the soul of the city.

Before going into the allegorical and character-building questions at the heart of my concern, I admit that I love this much about this crazy, super strange and imaginative city-birthing multiverse Jemisin has made. It allows Jemisin to highlight a brilliant city while working mythopoetically. However, I’m not sure yet if the fictional world holds together. I do not require the world-building cohesion that some readers expect, and I can go a long way with architectural experimentation. I am pleased to wait until future books to find out if Jemisin’s fictional world is a work of sophisticated beauty or simply nonsense–or, more likely, a flawed-but-intriguing multiverse in between. For now, though, it feels incomplete and in movement, which might contribute to how I think the moral reality destabilizes itself.

At the level of genre, while many individual elements work well, the allegorical layers go beyond what the novel’s structure can sustain. Jemisin is attempting to work an exceptionally sophisticated genre experiment, choosing to use allegory at various levels. If it was simply that the avatars were embodiments of boroughs and cities—like the creatures of Orwell’s Animal Farm or medieval conceptualizations of “Reason” or “Ira”—Jemisin could have probably avoided creating a formal allegory. It’s kind of genius, right? Conceptualizing a city in avatar form at a critical moment of its development, where the city lives or dies based upon its ability to summon all the strengths that are at the heart of what makes that city unique.

At the level of genre, while many individual elements work well, the allegorical layers go beyond what the novel’s structure can sustain. Jemisin is attempting to work an exceptionally sophisticated genre experiment, choosing to use allegory at various levels. If it was simply that the avatars were embodiments of boroughs and cities—like the creatures of Orwell’s Animal Farm or medieval conceptualizations of “Reason” or “Ira”—Jemisin could have probably avoided creating a formal allegory. It’s kind of genius, right? Conceptualizing a city in avatar form at a critical moment of its development, where the city lives or dies based upon its ability to summon all the strengths that are at the heart of what makes that city unique.

However, Jemisin allegorizes all sorts of things in the novel beyond the boroughs or the cities, including moral choices, strengths and failures, personality traits, temptations and trials, instincts and intuitions, artistic vision, and various kinds of critical intelligences and military strengths. More than the virtues and vices of older ages who find themselves awakening as characters in a tale, these traits are part of the avatars who embody the city’s communities. And yet they also become the weapons and tools for the great battle in The City We Become.

Critical to the tale is how the avatars represent key realities within the city. Some things seem incidental, like an avatar’s gender or race or sexuality. Even then, however, it is not clear that these are pure accidents, as we see in the case of the Bronx’s avatar, a Lenape woman—a brilliant device to provide the newly born city team with roots, while evoking a plethora of other intimations and consequences related to history, race, identity, economics, and relationality. That Manhattan (Manny) is new to the city and Queens is an immigrant is beyond what is specifically necessary. But in wanting a newcomer to the city and an immigrant on the superhero team, those choices are not without some kind of connection to the character of those communities.

Critical to the tale is how the avatars represent key realities within the city. Some things seem incidental, like an avatar’s gender or race or sexuality. Even then, however, it is not clear that these are pure accidents, as we see in the case of the Bronx’s avatar, a Lenape woman—a brilliant device to provide the newly born city team with roots, while evoking a plethora of other intimations and consequences related to history, race, identity, economics, and relationality. That Manhattan (Manny) is new to the city and Queens is an immigrant is beyond what is specifically necessary. But in wanting a newcomer to the city and an immigrant on the superhero team, those choices are not without some kind of connection to the character of those communities.

Thus, I suspect that none of the personal traits of the avatars are totally random (though doubtless many things emerge organically in the writer’s imagination). The avatars are more than people but nothing less than a true representative of their part of the city. In The City We Became, it is absolutely critical that the Bronx is pictured in one way and Staten Island another—not just in their superpowers, or in the way they relate to the other heroes and villains of the tale, but in all their prejudices and personalities and perspectives about what is possible.

The characters are avatars of a culture and thus allegorically significant on that level. The tools at their disposal also work on a number of symbolic layers. But the battle itself—the fight between New York as a newborn and the ancient, alien Foe, the struggle between the hopeful child and the devouring dragon (as I described in Part 1)—do we see allegorical representation here too? If you were writing New York as a lover of New York City in the late Trump era, how would you allegorize the great battle of today’s age?

The characters are avatars of a culture and thus allegorically significant on that level. The tools at their disposal also work on a number of symbolic layers. But the battle itself—the fight between New York as a newborn and the ancient, alien Foe, the struggle between the hopeful child and the devouring dragon (as I described in Part 1)—do we see allegorical representation here too? If you were writing New York as a lover of New York City in the late Trump era, how would you allegorize the great battle of today’s age?

I love New York City. It is one of my favourite places on the planet. But New York is not just city lights and drum circles and street rap battles and coffee and Off Broadway shows and the 10,000 things you love. Racism—and other forms of violence, discrimination, bigotry, and cruelty—are part of the make-up of the city. New York is built on blood and bone, beads and broken promises, as well as all of its talent and determination and perseverance. New York is a city of others. It is a city of migration—newcomers taking a breath and their first step out of the station into the street, the great promise of the immigrant seeking a new future, the forced immigration of racial and economic slavery that is New York’s history, the whelming tides of out-migration of its first peoples.

New York cannot just be made up of my favourite things: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Central Park, the High Line, the New York Public Library (with the lions), the Lego store, the original Ray’s pizza, my favourite ramen place on the continent, some of the last great bookstores on the planet, and the character of the city in half my favourite films and TV shows. It’s the other things too, the things not in the brochures.

There are many cities in New York. How many of them does my New York leave out? New York does not have one voice or five, but myriad voices. And while there are harmonic resonances in the song that is New York, these voices are often dissonant.

There are many cities in New York. How many of them does my New York leave out? New York does not have one voice or five, but myriad voices. And while there are harmonic resonances in the song that is New York, these voices are often dissonant.

So, how do you hold all of these tensions together in an allegorical battle for the soul of the city? As cool as this story wants to be as an embodiment of New York, it falls. It could be that it is simply too much to hold together, or that more time and distance is needed to understand New York City. In any case, despite all of the imaginative and provocative qualities of the text, in Jemisin’s execution of the allegory, the moral foundation of the story begin to crumble.

One of the beautiful lessons of this age is that a commitment to diversity and inclusion is a definitive moral stand. As such, it has limits that can be transgressed. Acts of racism and homophobia are used in the novel to further the Foe’s cause and create a potentially fatal rift between Staten Island and the other boroughs. I think this is a smart choice for Jemisin. Not only is bigotry an immediate threat to many people—folks with real challenges in the real city at this moment of my writing—but it is also a cancer to a great society.

Quite frankly—and here I am sharing my personal religious vision that Jemisin and her readers may not share—I believe that here in the reader’s world, we are in a cosmic battle against evil that can manifest itself in racism, sexism, and the personal and institutional cruelty and violence that haunt our communities and that Jemisin stands against in this novel. Thus, I am sympathetic to Jemisin’s novel as antiracist, antisexist, and anti-bigoted allegorical warfare, both within the text and against a culture that sees the world differently.

It is essential that this is a moral tale. And allegory may be a tool for representing such a moral stand in symbolical form. This, however, fails in various ways.

It is essential that this is a moral tale. And allegory may be a tool for representing such a moral stand in symbolical form. This, however, fails in various ways.

For one, there is a great deal of inelegant writing that neither works in an allegorical mode nor highlights the characters well—including dozens of expletives and exclamations that have the storytelling force of “golly gee wow!” or “aw shucks!” in dialogue. This Batman “kapow!” bubble writing in a novel does not show Jemisin at her finest. I don’t know if an allegory can be vulgar, but I think a New York allegory must have a great deal of vulgarity. I just don’t think it is executed very well.

At other points, the interior-exterior narrator is so preachy and condescending that it just reads like an after-school special filled with meaningful glances, eyebrow conversation, and campy accents. There are a few rare moments in Jemisin’s short stories that I don’t think work, but nothing that grates like some of this descriptive prose. This is a real disappointment, for there are moments in this novel where, in the midst of battle, the description evokes the moral vision and allegorical power of Jemisin’s tale with beauty and depth—including well-placed expletives and great moral stands.

But it’s the preaching in between that makes me cringe. Combine a narrator in the midst of self-righteous condescension with the cartoon dialogue of partly-formed allegorical figures, and then add a sense of embattled paranoia—heightened, we must admit, by real tensions in the storyline—and The City We Became starts to feel eerily familiar to me. I spent too many of my young adult years trying to find sympathy with terrible American Evangelical novels to desire a return to this mode of storytelling—or, frankly, this mode of moral exhortation.

For good moral storytelling to work it also must be good art. N.K. Jemisin is one of this generation’s great artists, but world-building, description, and moral exhortation do not always work together in this novel.

Especially, though, there is the question of character development at the heart of Jemisin’s moral tale.

In Part 1 of this article and at points above, I hope I have described how rich and dynamic many of the characters are. The four main boroughs on the side of the good—representing the Bronx, Manhattan, Queens, and Brooklyn—are rich in detail, carefully complex, and well-suited to their task. It is great fun to see these boroughs come alive—and to see the monsters and allies writhe and dance their way through the streets of New York.

What about what happens in Staten Island?

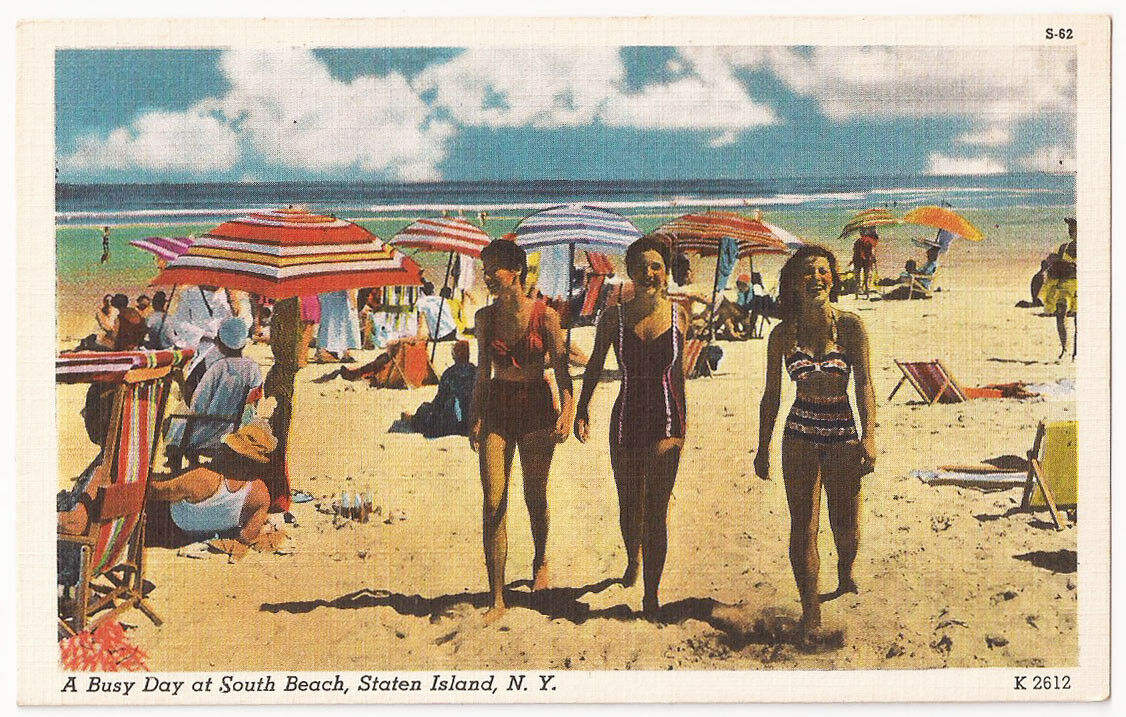

Aislyn Houlihan, Staten Island’s avatar, awakes to her city-consciousness alone and frightened, but is not sought out from the others for some time. Jemisin hints in the text that this is a weakness for the superheroes, since most of New York tends to count Staten Island out. A sociopolitical outlier, Staten Island’s forgottenness is conceptualized in Aislyn, a thirty-something white woman, sad and alone, under-educated, under-employed, and under her father’s brutal control. Aislyn feels safest in her white, middle-class borough, far away from the colourful dangers of the city.

Aislyn Houlihan, Staten Island’s avatar, awakes to her city-consciousness alone and frightened, but is not sought out from the others for some time. Jemisin hints in the text that this is a weakness for the superheroes, since most of New York tends to count Staten Island out. A sociopolitical outlier, Staten Island’s forgottenness is conceptualized in Aislyn, a thirty-something white woman, sad and alone, under-educated, under-employed, and under her father’s brutal control. Aislyn feels safest in her white, middle-class borough, far away from the colourful dangers of the city.

Staten Island is, indeed, set off, more white than the rest of the city, and more traditionalist, conservative, and Republican. Drawing Aislyn as hesitant about her identity with respect to the rest of the city is interesting. The inter-borough conflict works well here as well as between the other four boroughs. Giving Aislyn a kind of inherited family racism that makes her initially resist help from “foreigners” is a bold move—especially as the Foe is able to work as a devil on Aislyn’s shoulder, helping stir feelings of isolation and discomfort that fits so very well into the racist tropes Aislyn has imbibed.

It works well in concept, but the lines that Jemisin draws in this character and her world are problematic.

It works well in concept, but the lines that Jemisin draws in this character and her world are problematic.

Aislyn’s racism is a pressure she feels intimately within her own home. As in so many American households, Aislyn’s father is blatantly racist—as well as sexist and homophobic and anti-hipster (which is, perhaps, not the same level of moral failure). However, in one of the least elegant aspects of a novel about cultural curiosity and growth in perspective, Aislyn’s father, Captain Houlihan, fits every male Irish cop stereotype that tiresome TV dramas trope out in their casual and unreflective racism. There are other inelegancies in this part of the writing, such as the ways that Capt. Houlihan—”Houlihan” an Irish name for “proud,” evoking the Proud Boys movement—uses his brutalizing power in racist policing–not inaccurate, just not as effective as it could be. Likewise, it is a bit tiresome how the narrator tsk-tsks each of the family members in turn. Aislyn’s inner tension and the resulting city chaos that follows could work really well along lines of racism, bigotry, ignorance, and villainization of the other. But I went cold as I read the alcoholic, racist, controlling, abusive, hate-filled, crooked Irish cop in the pages. Google “Irish American stereotypes” and you can see that Jemisin takes up the most long-enduring sentiments of New York’s anti-ethnic prejudices and rolls them all into one character.

All, it is important to note, in a moral lesson about how Aislyn—the stand-in for Staten Island as well as Republicans and conservatives—might end up destroying the entire city because she lacks the moral courage to distrust her family’s prejudices and open her heart to the gifts of the city’s diversity.

I suppose we could set this aside as simply a writing shortcut. An abusive, racist male cop comes to mind in the midst of a Black Lives Matters movement that has excited peace-loving imaginations but systematic change seems lacking. Google searches help fill in the Irish identity.

I suppose we could set this aside as simply a writing shortcut. An abusive, racist male cop comes to mind in the midst of a Black Lives Matters movement that has excited peace-loving imaginations but systematic change seems lacking. Google searches help fill in the Irish identity.

Unless I missed it, however, there is not a single white male character with a speaking role who is not racist.

Not just in their hearts, I mean, but actively committed to racism as a cause.

The two white males we meet on Staten Island use strength and power and systems to perpetrate real oppression—all the while using Irish heritage as a convenient cover. And the group of white men we meet in the Bronx are part of a well-organized alt-right movement. They employ a stunning array of racist images and tools to do their work. Moving past social media terrorism, blatant stereotypes, and bad art, they are willing to burn down a building with people inside because of their beliefs.

Now, I’m not talking about representation. The alt-right attack and counter-attack are some of Jemisin’s best work in the novel. Much of this battle is well written and satisfying to read, including a Lovecraftian scene of trans-dimensional demonic energy that is a thing of beauty. Far from going out of her way to seize a stereotype of white young men, Jemisin has radically understated the damage of certain groups and movements to our communities. New Yorkers of colour, especially poor New Yorkers, know what it feels like to live in that surveillance city. A thousand pages of these characterizations would not begin to name the violence and hatred that is both on the street and in the system.

Now, I’m not talking about representation. The alt-right attack and counter-attack are some of Jemisin’s best work in the novel. Much of this battle is well written and satisfying to read, including a Lovecraftian scene of trans-dimensional demonic energy that is a thing of beauty. Far from going out of her way to seize a stereotype of white young men, Jemisin has radically understated the damage of certain groups and movements to our communities. New Yorkers of colour, especially poor New Yorkers, know what it feels like to live in that surveillance city. A thousand pages of these characterizations would not begin to name the violence and hatred that is both on the street and in the system.

I’m also not criticizing the fact that Jemisin’s team of city-fighters on “the good side” includes no white or Jewish people. A book like this needs a Scoobie Gang, a Crew of Light, a gathering of somewhat reluctant heroes who must save the world from the Foe. Any crime-fighting fellowship is meant to draw in diverse experiences. Avengers and A-teams are only as good as the different gifts they bring to the adventure. Without Ron and Hermione and Dumbledore’s Army, Harry is just a scarred, violence-entwined, demonically empowered, floppy-haired orphan with curiosity, intelligence, and awkward charm. Leagues of Extraordinary Gentlemen need to be extra-ordinary, after all. Sometimes, the extraordinary gentlemen aren’t all normal white men.

And remember, diversity is key to what the city is. 2020s New York is not late 20th-century Sunnydale or how Victorian London exists in our public imagination. Thus, the embodiment of New York is colourful, dynamic, and explosive—and far more diverse in its diversities than most of the fictional worlds we inhabit. The point of an ensemble cast is its unique assembly, and the adventure that follows is one where the seemingly random and incongruous members of the Foe-fighting crew end up being precisely who and what was necessary in the moment of direst need.

And remember, diversity is key to what the city is. 2020s New York is not late 20th-century Sunnydale or how Victorian London exists in our public imagination. Thus, the embodiment of New York is colourful, dynamic, and explosive—and far more diverse in its diversities than most of the fictional worlds we inhabit. The point of an ensemble cast is its unique assembly, and the adventure that follows is one where the seemingly random and incongruous members of the Foe-fighting crew end up being precisely who and what was necessary in the moment of direst need.

Thus, the ensemble cast of the non-Staten Island characters works at a number of levels (even when their dialogue stutters or the narrator “tells” instead of “shows”).

No, when I say that the moral foundation of Jemisin’s allegory crumbles, I mean that Jemisin has fallen against the very Foe that she allegorizes.

Her characters on the side of the “good” are lovingly drawn, filled with major flaws and critical strengths. They are each verdant embodiments of the city she loves.

Her characters on the side of the “good” are lovingly drawn, filled with major flaws and critical strengths. They are each verdant embodiments of the city she loves.

By contrast, Aislyn and her father, the other white Irish racist in Staten Island, and the alt-right terrible artists-slash-terrorists are all editorial cartoons: thin-lined in character though essential to the action. Aislyn, who might end up developing the courage to think for herself in book two, has occasional moments that some readers might appreciate. But she is ceaselessly annoying—not sympathetically sad, except in her moments of greatest evil. She does not even have the moral courage to commit to the good old-fashioned racism that has so enveloped her thinking.

These are hardly characters at all, but only two-dimensional figures to contrast the real people of depth, the ones who share Jemisin’s ideological perspective.

The one exception is the Foe, a well-drawn villain—though one whose storyline slips away unfinished. It could be that the one other white woman with lines, Aislyn’s mother, isn’t fully racist but only pretending to live that way. However, that the only compelling figure on the “bad” side, the Foe, is called “Mrs. White” in a novel where all of the white characters are not simply ignored but actively vilified, is … well, I don’t know what to say about that.

It could be this is all accidental, or that I am over-reading the situation. Perhaps I missed a super cool white guy somewhere, well-rounded and with a speaking part that I didn’t remember. It could be coincidence—as it might be a coincidence that the only redhead in the novel is also super racist.

And it could be that Jemisin is caught between writing spheres, using allegory in an age where we read novels. Allegory, like fairy tale, requires a certain kind of elemental or moral embodiment in its characters. Though Aislyn might end up being something more, perhaps the characters on the side of the Foe are very much the caricatures, parodies, or archetypes that can work in this mode.

And it could be that Jemisin is caught between writing spheres, using allegory in an age where we read novels. Allegory, like fairy tale, requires a certain kind of elemental or moral embodiment in its characters. Though Aislyn might end up being something more, perhaps the characters on the side of the Foe are very much the caricatures, parodies, or archetypes that can work in this mode.

However, my concern about character development is not about the genre she chooses. My concern is that, even in allegory or fairy tale, or the kind of science fiction writing where not all the characters need to be worked out in all of their psychological depths, the author must respect her characters. Even the villains. Even the insipid characters—the cutthroats, cowards, deserters, smarmy politicians, and past-suited pissants. Even the quiet racists and their collaborators who ensure the continuation of bigotry and poverty in America. For this story to work, Jemisin must draw the heroic and heartless villains as well as she draws the daring and doubt-filled heroes.

After all, the very heart of this moral tale is about the richness of diversity, the humanness of the other, the power of the voices of the forgotten, and a cosmic stand against ignorance, hatred, and violence against the oppressed.

As a master in her field, there is a lot to admire in this new book, particularly in conceptualizing a speculative framework that is both psychological and mythic. I share Bronca’s belief that good art can inspire, transform, liberate, and transcend the mundane without being inorganic to its roots. Thus, I want this novel to win, as I want New York City to eject this Foe. Because I believe in the core message, I want this novel to be good art and thus effective cultural criticism. As an allegory, however, it fails to be compelling, even for those who are sympathetic to much of its moral core. And, ultimately, the moral foundation of the novel crumbles because the villains are drawn using the tools of the Foe rather than envisioned powerfully within the heart of that great city.

Blogging the Hugos 2021 (Tentative Schedule)

I believe in open access scholarship. Because of this, since 2011 I have made A Pilgrim in Narnia free with nearly 1,000 posts on faith, fiction, and fantasy. Please consider sharing my work so others can enjoy it.

Hugo Award 2021: Best Novel Roundtable

Hugo Award 2021: Best Novel Roundtable  Brenton’s Pre-Roundtable Reflections on the Blogging the Hugos Series

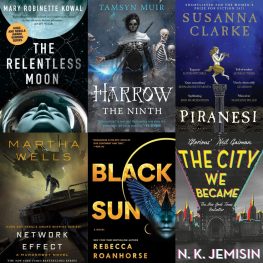

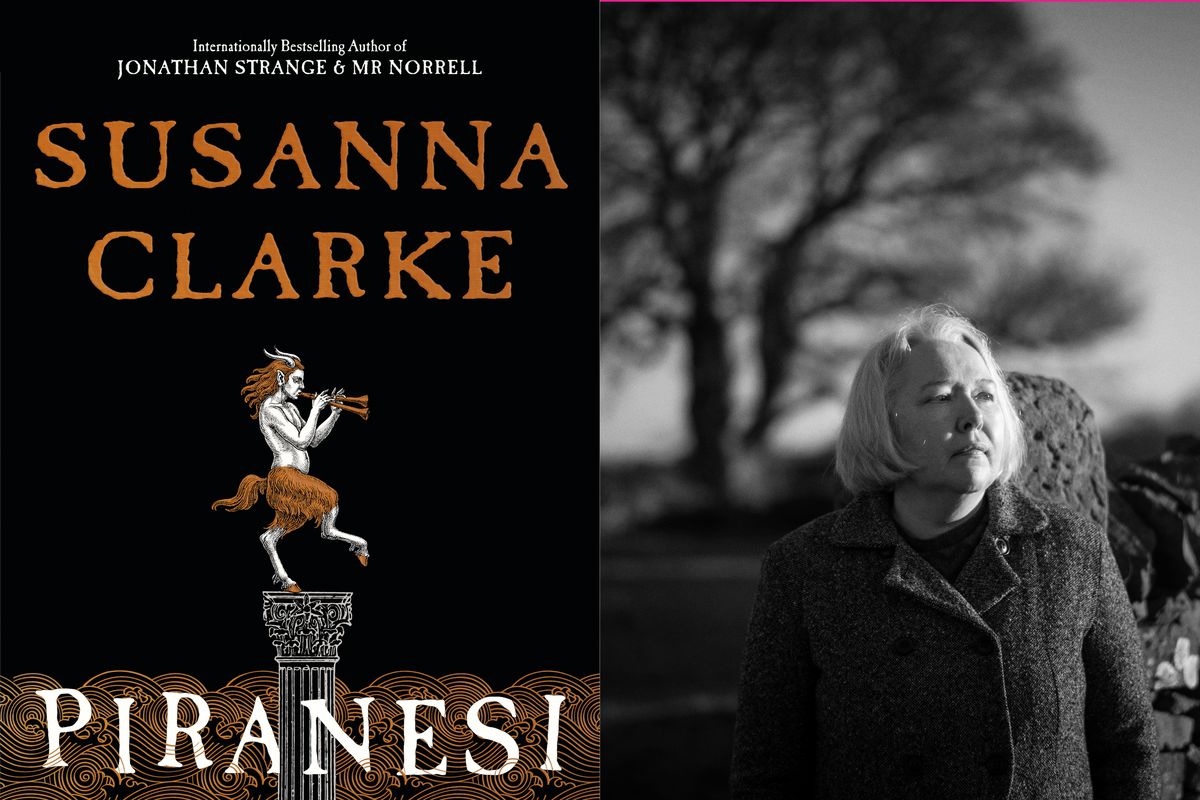

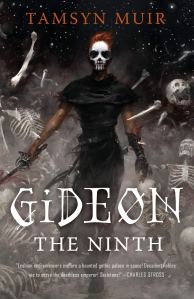

Brenton’s Pre-Roundtable Reflections on the Blogging the Hugos Series As in 2021, the award shortlist includes six highly influential and productive women sf writers. Five of the novels are part of book series, though the outlier–Susanna Clarke’s long-awaited novel, Piranesi, has its own complexities as novel referencing other work. Moreover, I felt I needed to finally read her vivid, game-changing 2004 Regency-era fantasy, Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, to discern any links that may be there. While I was able to enjoy Martha Wells’ Network Effect without reading the other stories, it was absolutely essential to read Tamsyn Muir’s Gideon the Ninth before this year’s nomination, Harrow the Ninth. And though it is possible to read Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Relentless Moon, without the two preceding novels in the series, The Calculating Stars was a refreshing discovery. With The Fated Sky, I was able to read Kowal’s newest Hugo nomination with a full sense of the Lady Astronaut Universe.

As in 2021, the award shortlist includes six highly influential and productive women sf writers. Five of the novels are part of book series, though the outlier–Susanna Clarke’s long-awaited novel, Piranesi, has its own complexities as novel referencing other work. Moreover, I felt I needed to finally read her vivid, game-changing 2004 Regency-era fantasy, Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, to discern any links that may be there. While I was able to enjoy Martha Wells’ Network Effect without reading the other stories, it was absolutely essential to read Tamsyn Muir’s Gideon the Ninth before this year’s nomination, Harrow the Ninth. And though it is possible to read Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Relentless Moon, without the two preceding novels in the series, The Calculating Stars was a refreshing discovery. With The Fated Sky, I was able to read Kowal’s newest Hugo nomination with a full sense of the Lady Astronaut Universe.  And of the book that I was assigned, Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi?

And of the book that I was assigned, Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi? This is the second year in a row where women have dominated the list.

This is the second year in a row where women have dominated the list. Of this year’s novels, Rebecca Roanhorse’s Black Sun is most clearly in the realm of legendary fantasy, while Mary Robinette Kowal and Martha Wells are writing in classical SciFi modes. The other three books are literary blends, so that N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became is an urban apocalypse in allegorical form, Tamsyn Muir’s Locked Tomb series luxuriously combines a handful of fantastic, romantic, and science fiction genres, and Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi is … well, I’m not quite sure yet what. As a philosophical novel, it has mythic, fantastic, and science fiction elements–though the reader must make some choices about what is fantasy and what is science fiction.

Of this year’s novels, Rebecca Roanhorse’s Black Sun is most clearly in the realm of legendary fantasy, while Mary Robinette Kowal and Martha Wells are writing in classical SciFi modes. The other three books are literary blends, so that N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became is an urban apocalypse in allegorical form, Tamsyn Muir’s Locked Tomb series luxuriously combines a handful of fantastic, romantic, and science fiction genres, and Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi is … well, I’m not quite sure yet what. As a philosophical novel, it has mythic, fantastic, and science fiction elements–though the reader must make some choices about what is fantasy and what is science fiction. However, even with Jemison—certainly a giant in the field of Science Fiction writing today—it would be unfortunate to count out Mary Robinette Kowal, whose The Calculating Stars kicked off the Lady Astronaut series with a Hugo win in 2019. Fellow SciFi writer Martha Wells has been publishing for decades, including a Nebula nomination in 1999 for The Death of the Necromancer and Hugo nominations and wins for novellas and book series. She has carefully shaped the Murderbot Diaries series that includes this year’s nominee, Network Effect—and has had the entire series nominated. On top of this, Network Effect is the novel that won the Nebula award earlier this year.

However, even with Jemison—certainly a giant in the field of Science Fiction writing today—it would be unfortunate to count out Mary Robinette Kowal, whose The Calculating Stars kicked off the Lady Astronaut series with a Hugo win in 2019. Fellow SciFi writer Martha Wells has been publishing for decades, including a Nebula nomination in 1999 for The Death of the Necromancer and Hugo nominations and wins for novellas and book series. She has carefully shaped the Murderbot Diaries series that includes this year’s nominee, Network Effect—and has had the entire series nominated. On top of this, Network Effect is the novel that won the Nebula award earlier this year. It really is a fantastic set of books, if you can forgive the stellar pun.

It really is a fantastic set of books, if you can forgive the stellar pun. Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Relentless Moon and the Lady Astronaut Universe (11/10/21)

Mary Robinette Kowal’s The Relentless Moon and the Lady Astronaut Universe (11/10/21)