It was pouring rain in Portland as Nicolas and I wove our way through the artisan-filled streets of this renewed East Coast City. I love Portland, though we were not visiting on the best of circumstances. Just a couple of hours earlier, with too little sleep, Nicolas and I had left a sunny Boston behind. Our pilgrimage complete, we had seen one of our favourite bands, Twenty One Pilots, live at the Gardens. Boston is only a 10 or 11 hour drive from where we live, so it is worth the time and money when the right conference or concert comes our way. That we left Prince Edward Island only a few hours after I had landed from my research trip to England was part of the fun. The torrential rain would later become heavy snow as we headed North to Canada, causing us to seek refuge in a nondescript roadside motel. But we were still riding high as we hit Portland with one destination in mind: The Green Hand.

It was pouring rain in Portland as Nicolas and I wove our way through the artisan-filled streets of this renewed East Coast City. I love Portland, though we were not visiting on the best of circumstances. Just a couple of hours earlier, with too little sleep, Nicolas and I had left a sunny Boston behind. Our pilgrimage complete, we had seen one of our favourite bands, Twenty One Pilots, live at the Gardens. Boston is only a 10 or 11 hour drive from where we live, so it is worth the time and money when the right conference or concert comes our way. That we left Prince Edward Island only a few hours after I had landed from my research trip to England was part of the fun. The torrential rain would later become heavy snow as we headed North to Canada, causing us to seek refuge in a nondescript roadside motel. But we were still riding high as we hit Portland with one destination in mind: The Green Hand.

The Green Hand is testimony to the fact that one of the best gifts that Science Fiction has given us is time travel. Stepping into the Green Hand is like stepping back a generation, in the days before big warehouse bookstores become the digital and analog norm. While Portland has a number of great indie bookstores, the Green Hand is entirely dedicated to speculative fiction: fantasy, ghost stories, horror, the supernatural, the weird, classic and contemporary SciFi, and all manner of genre fiction at the edges of our imaginative possibilities. The Green Hand is my destination for hard-to-find Stephen King and Ursula K. Le Guin editions or stumble-upon classic sf discoveries. It takes hours to truly explore the store, including occasional deposits of pirated fan papers like early Tolkien language guides. That it has an entire section dedicated to Philip K. Dick says much.

The Green Hand is testimony to the fact that one of the best gifts that Science Fiction has given us is time travel. Stepping into the Green Hand is like stepping back a generation, in the days before big warehouse bookstores become the digital and analog norm. While Portland has a number of great indie bookstores, the Green Hand is entirely dedicated to speculative fiction: fantasy, ghost stories, horror, the supernatural, the weird, classic and contemporary SciFi, and all manner of genre fiction at the edges of our imaginative possibilities. The Green Hand is my destination for hard-to-find Stephen King and Ursula K. Le Guin editions or stumble-upon classic sf discoveries. It takes hours to truly explore the store, including occasional deposits of pirated fan papers like early Tolkien language guides. That it has an entire section dedicated to Philip K. Dick says much.

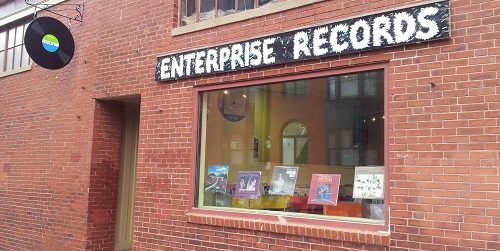

Heading back to the car, we popped into Enterprise Records. Our excuse was to let the hardest rain pass by, but it is hard to resist the lure of used vinyl. There are a few great places in Downtown Maine, like Moody Lords and Electric Buddhas, but Enterprise Record’s vintage sign and straight-up bin-discovery set-up means there is usually something to find for collectors and something leftover for abecedarians like me. This time, I was content to find a $3 Abbey Road–playable, but not good enough to be collectable.

Heading back to the car, we popped into Enterprise Records. Our excuse was to let the hardest rain pass by, but it is hard to resist the lure of used vinyl. There are a few great places in Downtown Maine, like Moody Lords and Electric Buddhas, but Enterprise Record’s vintage sign and straight-up bin-discovery set-up means there is usually something to find for collectors and something leftover for abecedarians like me. This time, I was content to find a $3 Abbey Road–playable, but not good enough to be collectable.

On a whim, I checked the audiobook bin and made a startling discovery. I found a beautiful, library withdrawal copy of the Nicol Williamson’s abridged reading of The Hobbit. Although there are some pirated versions of this edition that make their way through the Tolkienist versions of the not-so-mirky web (i.e., it’s on Youtube), the LP is a pretty rare find. I was able to get this copy in pretty good shape for $30–a bargain at twice the price, though still a conversation I would have to have with my very patient wife.

On a whim, I checked the audiobook bin and made a startling discovery. I found a beautiful, library withdrawal copy of the Nicol Williamson’s abridged reading of The Hobbit. Although there are some pirated versions of this edition that make their way through the Tolkienist versions of the not-so-mirky web (i.e., it’s on Youtube), the LP is a pretty rare find. I was able to get this copy in pretty good shape for $30–a bargain at twice the price, though still a conversation I would have to have with my very patient wife.

I am hardly any kind of collector as so many Tolkienists are. I have a US 1st edition of The Silmarillion, which I got for $10 at a used bookstore in Vermont where the owner did not seem like she wanted to sell any of her books. I have a nice boxed anniversary edition of The Hobbit, printed beautifully and well-illustrated. I have that original wide-sized printing of the Tolkien-illustrated Mr. Bliss, and I purchased the Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth Bodleian coffee table book because I love Tolkien’s work in pen and ink. And I like the look of my UK 2nd edition Lord of the Rings on the shelf, though nothing of mine is terribly valuable.

What drew me to the Nicol Williamson recording was my particular love of well-produced audiobooks or audio rarities, like the recordings of Tolkien that are now digitally available but were once pretty hard to find. While I would normally consider any abridgement a kind of literary sin–more because of the terrible quality of most abridgments rather than any authorial loyalty–this version has become a kind of cult classic. I have no interest in Martin Shaw’s abridged reading, but I was curious about this Nicol Williamson LP. I only found out later that I had done well in the bargain.

What drew me to the Nicol Williamson recording was my particular love of well-produced audiobooks or audio rarities, like the recordings of Tolkien that are now digitally available but were once pretty hard to find. While I would normally consider any abridgement a kind of literary sin–more because of the terrible quality of most abridgments rather than any authorial loyalty–this version has become a kind of cult classic. I have no interest in Martin Shaw’s abridged reading, but I was curious about this Nicol Williamson LP. I only found out later that I had done well in the bargain.

Truth be told, listening to Tolkien’s tales on tape has produced mixed results for me. Nicol Williamson’s version is peppy and lively, very hobbit- and dwarf-focussed, bringing dialogue and adventure to the front of the story. For a Hobbit audiobook, I prefer Rob Inglis’ voice in the unabridged reading–including all the little details that, for me, make The Hobbit a gateway to Tolkien’s epic. Right now, I am listening to Inglis’ version of The Lord of the Rings and quite enjoying it. I don’t love the voicing of Gimli and Legolas–I think Peter Jackson‘s characters have burrowed into my imagination–but Inglis brings the world alive for me, creaky singing voice and all.

Truth be told, listening to Tolkien’s tales on tape has produced mixed results for me. Nicol Williamson’s version is peppy and lively, very hobbit- and dwarf-focussed, bringing dialogue and adventure to the front of the story. For a Hobbit audiobook, I prefer Rob Inglis’ voice in the unabridged reading–including all the little details that, for me, make The Hobbit a gateway to Tolkien’s epic. Right now, I am listening to Inglis’ version of The Lord of the Rings and quite enjoying it. I don’t love the voicing of Gimli and Legolas–I think Peter Jackson‘s characters have burrowed into my imagination–but Inglis brings the world alive for me, creaky singing voice and all.

Still, I remain a little hesitant. I did not love the bits of the dramatized versions that I have heard of The Lord of the Rings–though I have it in a full audiocassette boxset if I want to give it a try. I liked the BBC’s Tales from the Perilous Realm stories, though Derek Jacobi wins the prize there, for me. I read Andy Serkis’ version of The Hobbit earlier this winter. It was excellently done, but I did not love it. When reading The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, I want the books in my hand–and not the fancy versions, but my trusty, cheap, well-worn paperbacks that I bought in Japan when I was missing the sound of the English tongue. So I have Timothy and Samuel West’s Beren and Lúthien and The Fall of Gondolin on my audible wishlist, as well as Christopher Lee’s The Children of Hurin, but I have never pulled the trigger. I see that Unfinished Tales will land on audio by the Wests, but I probably won’t pre-order it until I’ve read the other attempts.

Still, I remain a little hesitant. I did not love the bits of the dramatized versions that I have heard of The Lord of the Rings–though I have it in a full audiocassette boxset if I want to give it a try. I liked the BBC’s Tales from the Perilous Realm stories, though Derek Jacobi wins the prize there, for me. I read Andy Serkis’ version of The Hobbit earlier this winter. It was excellently done, but I did not love it. When reading The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, I want the books in my hand–and not the fancy versions, but my trusty, cheap, well-worn paperbacks that I bought in Japan when I was missing the sound of the English tongue. So I have Timothy and Samuel West’s Beren and Lúthien and The Fall of Gondolin on my audible wishlist, as well as Christopher Lee’s The Children of Hurin, but I have never pulled the trigger. I see that Unfinished Tales will land on audio by the Wests, but I probably won’t pre-order it until I’ve read the other attempts.

My hesitation is a little strange to me. I love audiobooks, and I think Beren and Lúthien one of the best things I have ever read. Also, Martin Shaw’s deep, resonant reading helped The Silmarillion come alive for me. While I had powered through–as I discuss here–now I reread the tale of the Silmarils with a new kind of delight. The audiobooks are a fun way to reread quite a number of the tales that might slide to the edge of my bookshelf otherwise. And yet it was that reading by Andy Serkis that made me yearn for the text itself rather than a storyteller’s interpretation in my ear.

My hesitation is a little strange to me. I love audiobooks, and I think Beren and Lúthien one of the best things I have ever read. Also, Martin Shaw’s deep, resonant reading helped The Silmarillion come alive for me. While I had powered through–as I discuss here–now I reread the tale of the Silmarils with a new kind of delight. The audiobooks are a fun way to reread quite a number of the tales that might slide to the edge of my bookshelf otherwise. And yet it was that reading by Andy Serkis that made me yearn for the text itself rather than a storyteller’s interpretation in my ear.

As I thought about this seeming contradiction, I realized that what the audiobooks were doing for me was to push me back to the text. This is undoubtedly a good thing. As I read (i.e. listened), I found myself wandering over to the bookshelf to look up a passage I had not noticed before.

The Andy Serkis reading of The Hobbit was fresh for me because his voicing of the text began to match with certain elements of the films that I had seen only years before. This is no surprise. Serkis was the voice of Gollum in the Peter Jackson films, including brief appearances in the first installment of the Hobbit trilogy. Back when they were released, I wrote reviews about the bumbled but interesting nature of the Hobbit films, admitting that I loved more of Tolkien’s world, but they had rather overdrawn the story. What was surprising to me, however, were a number of tiny text details that I had never noticed before that flashed into my mind as film images, provoked by Andy Serkis’ reading. These include little turns of phrase, particular details of costume, the habits and movements of the characters, and the way the poetry is capturing either an element of atmosphere, a critical point of lore, or foretelling an aspect of the adventure.

The Andy Serkis reading of The Hobbit was fresh for me because his voicing of the text began to match with certain elements of the films that I had seen only years before. This is no surprise. Serkis was the voice of Gollum in the Peter Jackson films, including brief appearances in the first installment of the Hobbit trilogy. Back when they were released, I wrote reviews about the bumbled but interesting nature of the Hobbit films, admitting that I loved more of Tolkien’s world, but they had rather overdrawn the story. What was surprising to me, however, were a number of tiny text details that I had never noticed before that flashed into my mind as film images, provoked by Andy Serkis’ reading. These include little turns of phrase, particular details of costume, the habits and movements of the characters, and the way the poetry is capturing either an element of atmosphere, a critical point of lore, or foretelling an aspect of the adventure.

In the original Jackson LOTR film trilogy, which I still love, there simply is not time for the long, luxurious time that The Fellowship of the Rings spends in Rivendell, particularly at the council–one of Tolkien’s longest chapters. In over-drawing the Hobbit films, however, there may be more details available to us than would have been the case with a nice, three-hour fairy-tale film like The Hobbit deserves. By an odd circuitous route, then–from the fan-favourite Nicol Williamson reading that was fun but unfulfilling, to the excellent Andy Serkis reading that I did not love, to the over-produced Peter Jackson films that I enjoyed with grave reservations–I have found what I love best about both audiobooks and adaptations: they send me back to the text richer, inspiring me to read more deeply and to hear the text with different voices.

In the original Jackson LOTR film trilogy, which I still love, there simply is not time for the long, luxurious time that The Fellowship of the Rings spends in Rivendell, particularly at the council–one of Tolkien’s longest chapters. In over-drawing the Hobbit films, however, there may be more details available to us than would have been the case with a nice, three-hour fairy-tale film like The Hobbit deserves. By an odd circuitous route, then–from the fan-favourite Nicol Williamson reading that was fun but unfulfilling, to the excellent Andy Serkis reading that I did not love, to the over-produced Peter Jackson films that I enjoyed with grave reservations–I have found what I love best about both audiobooks and adaptations: they send me back to the text richer, inspiring me to read more deeply and to hear the text with different voices.

It really is amazing what you might discover in downtown Portland!