At A Pilgrim in Narnia, we have an occasional feature called “Throwback Thursday.” By raiding either my own blog hoard or someone else’s, I find an article or review from the past and throw it back out into the digital world. This might be an idea or book that is now relevant again, or a concept I’d like to think about more, or even “an oldie but a goodie” that I think needs a bit of spin time.

I have just finished the Graphic Novel adaptation of The Graveyard Book. It was splendid. So I am reminded of my very first Neil Gaiman review of the novel. I still remember the feeling of listening to The Graveyard Book on CD during a family trip and thinking, “I could have thought of this, and I have had thoughts like that, but Gaiman got there first.” Sad, yes, but the darker question: “I could have done it … but could I have done it so well?” In one of those literary soul-searching inspirations, I wrote this original, somewhat saucy, and marginally bitter review. I think it still works–though it seems to me that moralistic tale-telling is on the rise again in this decade.

I continue to read and think about Neil Gaiman’s work. I am in the midst of TV adaptations of Good Omens and Sandman. Back in 2021, I published another somewhat edgy but thoughtful article on the Marvel Comics adaptation of C.S. Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters, and followed it up with Neil Gaiman’s preface to that work–a set of literary finds that will be new to many. I’ve written a short piece on Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett on friendship, linking an early life discovery he had while reading C.S. Lewis. And I once threw up a blog post, “Neil Gaiman on Discovering the Author in Narnia (and a note on beards),” which I still quite like. I am ever more convinced that this happily mad genius has penned what I believe to be the most important American fantasy novel, American Gods. Meanwhile, I hope you enjoy this review, risen from the grave and dressed up for today.

Neil Gaiman is a jerk.

Well, I don’t really mean that. On my own bookshelf alone, I can see a dozen books by new writers with his powerful recommendations. Gaiman has a rare give for collaborating and resonating with others. And I have heard rumours that he is really quite a nice human being.

But honestly, how many beautiful ideas is a guy allowed to have in a lifetime? There’s Coroline in all its forms, and his epic, American Gods. Beyond that, he has produced an incredible array of short stories and essays, works fluidly across various media, and practically invented a genre of literature with Sandman. I even heard that his The Ocean at the End of the Lane was voted best book in the universe or something, and with every streaming service begging for his artistic signature, he has started writing adaptations of his adaptations. I mean, seriously?

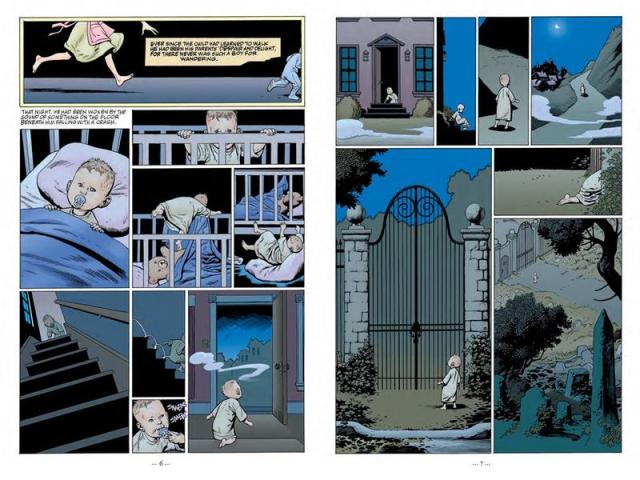

All deep-rooted bitterness aside, The Graveyard Book—you may remember I’m writing a review here—is based on a pretty elegant premise. An orphaned toddler wanders into a graveyard, and it is up to the dead people who live there to raise him. Brilliant.

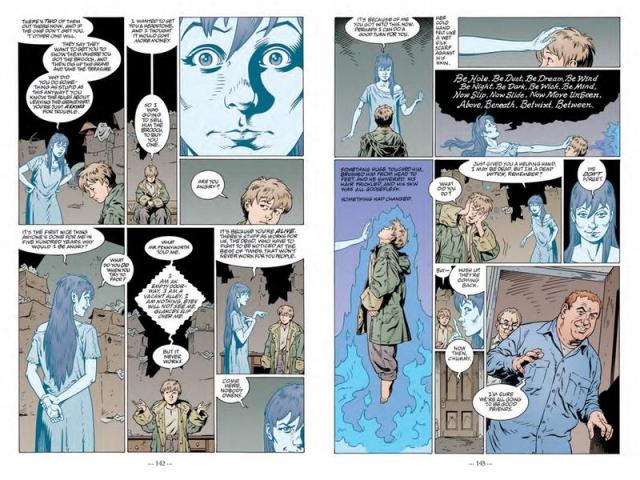

The Mowgli character in this liminal fantasy is “Nobody Owens.” He is raised by the disembodied spirits of various centuries who have remained in the graveyard and how grant “Bod” their transmortal protection. Needless to say, his education is eclectic. Because of his unique neighbourhood, Bod is able to speak the English of a hundred generations, though he has a very particular and narrow understanding of history. He learns to read English and Latin from the epitaphs on tombstones. With honourary citizenship in the graveyard, he also learns the particularly ghastly gifts of fading from view, dream walking, and haunting.

It is a very clever book, able to draw our cultural imagination of graveyards into a single bittersweet tale.

This is one of those great books that can work at various levels. I know, I know. Books that are tinged with meaning, morals, or symbolism have garnered a poor reputation as art. But The Graveyard Book does what good books should. I am always looking for a story that will capture the sense of alienation and loneliness I had when I was a child. What could be better than a boy named “Nobody” who is practically invisible to humans and lives in a place that doesn’t exist with people who can’t be there? Moreover, parents reading this book are going to be left with the haunting feeling—see what I did there?—that they are in some danger of over-protecting their children.

These morals emerge naturally from the narrative; none of them are forced. Critics of layered stories are missing the point, I think. Anyone reading Harry Potter would be a dangerously narrow reader if they didn’t see the social implications. Yet they read these books again and again because they are good works of literature that please and challenge both. The Graveyard Book is exactly that type of book, on a much smaller scale.

I’m not surprised it’s good. As soon as I heard the premise, even filled with weighty sadness of loss, I knew that it would be.

It is not a perfectly shaped book. Gaiman is a short story writer at his best, so the book is episodic, filled with flashes of Nobody’s life as he grows. They are usefully lively episodes, but, at times, the plotline feels like it is going nowhere. Gaiman makes it work here in much the same way that L.M. Montgomery‘s Anne of Green Gables is episodic and forward-moving. Like Anne Shirley, Nobody Owens’ life has a particular direction, as readers slowly come to understand. Some of the feeling of Bod’s destiny is lost in the triptych style of storytelling, so the climax and denouement are a bit quick, for me, at least. And there is the haunting question: How must a boy-in-the-graveyard coming-of-age tale end?

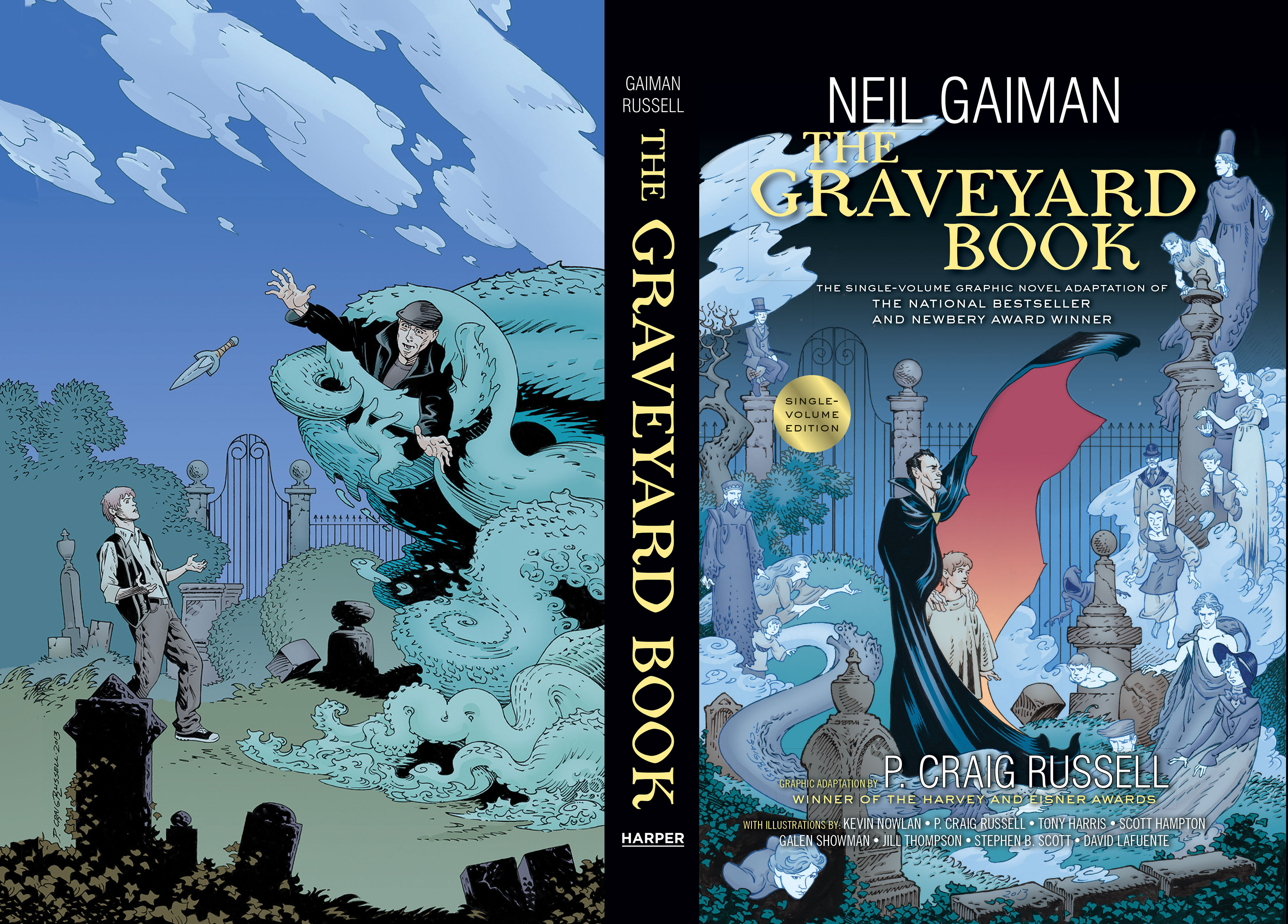

Neil Gaiman is part of the invention and growth of the adult graphic novel as a distinct storytelling artistic expression, and the adaptation is excellently done. Led by P. Craig Russell’s art direction, each of the different artists contributes a different vision of Bod’s world. Rather than visual chaos or a loss of unity, the artwork in each chapter is suited to Nobody’s personal growth and the reader’s expanding vision of his world, the graveyard. Given that there is an element of mystery here, the fact that the visualizations of the characters and scenes differ slightly keeps the visual learner from prematurely working out the clues.

Truly, The Graveyard Book has become one of my favourite graphic novels ever. I lost nothing in the abridgement and interpretation of the text and was won over again to the powerful atmosphere of the tale. For The Graveyard Book is not derivative, though it echoes other stories. It is not merely the retelling of Kipling’s classic, nor is it simply a stock orphan tale or standard coming-of-age story. It goes deeper than these elements, for The Graveyard Book is a messianic story, laced with prophecy and legend that moves through many millennia and a few dimensions. As I reread this book in a new form, I found that the mythic elements intensified for me–either in the act of drawing the story deeper into my consciousness, or because the graphic novel enhanced my reading experience.

Granular criticisms within a heap of praise. My real complaint is that Neil Gaiman is a jerk. And greedy too–though admittedly generous to many writers and artists. The Graveyard Book won not only the Newbery Medal but also took the Carnegie Medal (a first double win, I believe). If that wasn’t enough, Gaiman took home the Hugo and Locus awards. How are other writers supposed to build a career when this guy is sitting down at a computer with his elegant premises, whimsical hair, and friendships with amazing illustrators?

Anyway, readers may note a touch of bitterness. I would hate for my grave feelings about Gaiman in the moment of rereading to overshadow what is a very great novel that is successfully transformed within another of Gaiman’s transmedial projects. But don’t buy it. That will just help his cause. Have your library order it but read it there to make it seem less popular. Or read it in the aisle at the bookstore or over someone’s shoulder on the bus. If you can make yourself invisible like Nobody, no one will find that creepy at all.

Today is

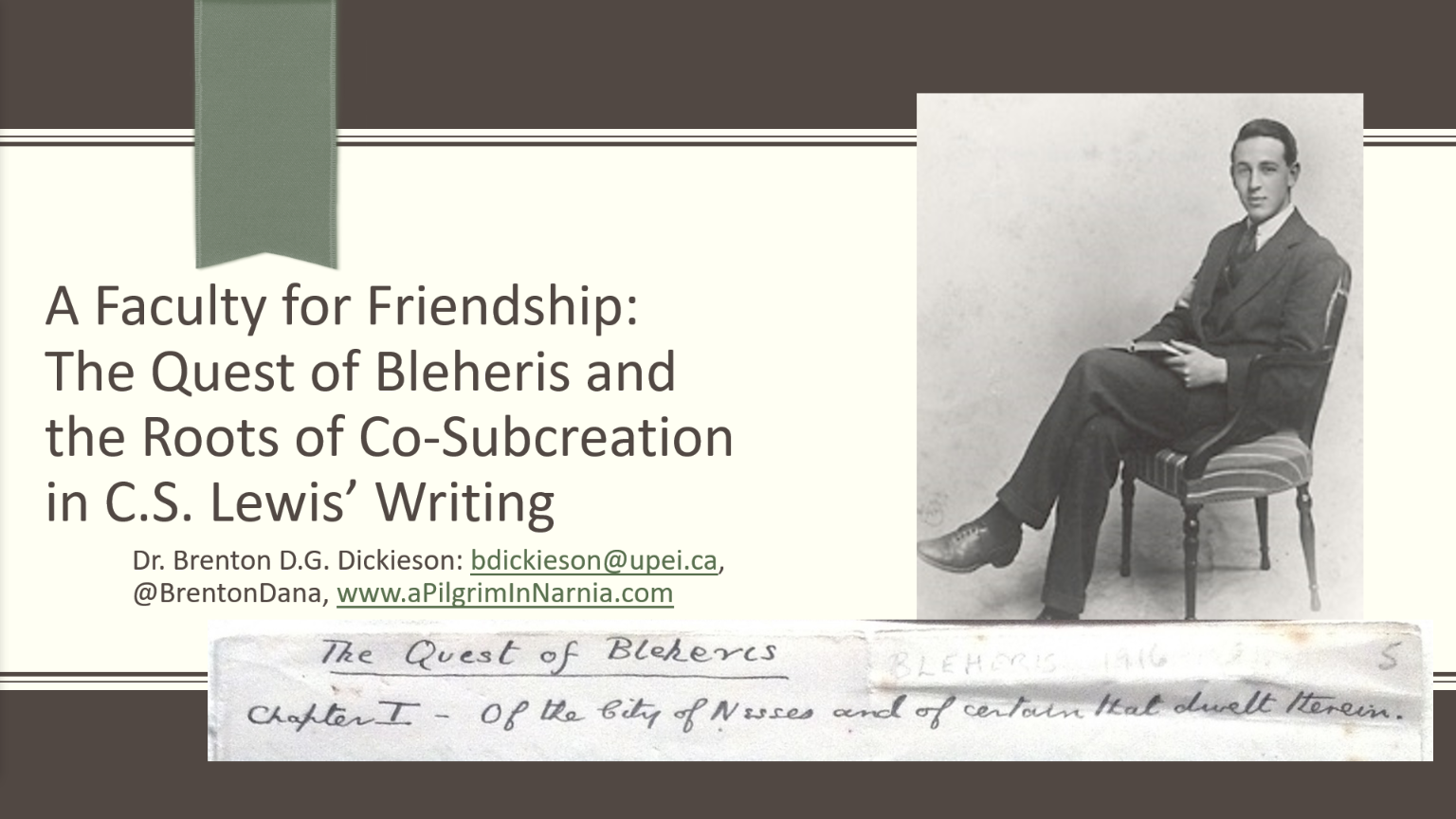

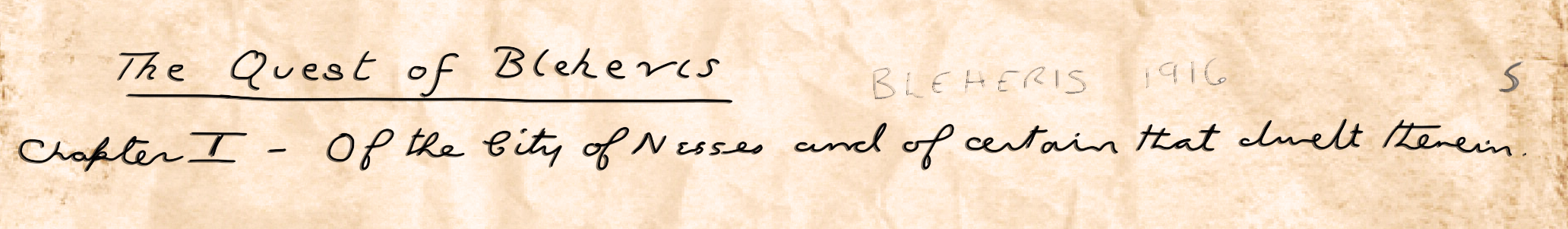

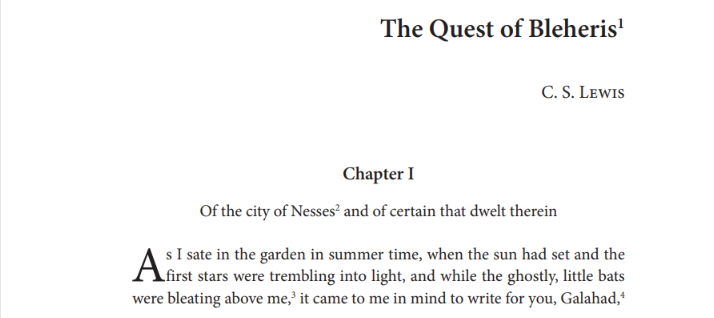

Today is  I am pleased to have been selected to give a paper at Mythmoot X in Leesburg, VA. I have spoken quite a bit about teaching with

I am pleased to have been selected to give a paper at Mythmoot X in Leesburg, VA. I have spoken quite a bit about teaching with