While I love the Odyssey, I always dread returning to The Iliad. I just find all the war and posturing and characters to be ash and dust and thorn for me, just weariness and work and pain. The moments of greatness within The Iliad do not lift me like many of the classics that sit behind the cultures in which I was raised. Perhaps it is that with every loved one I bury in my life, with every heap of ashes I scatter in the wind or every coffin lowered into the ground and every prayer book incantation I utter, I care less for Homer’s great epic of war and loss.

While I love the Odyssey, I always dread returning to The Iliad. I just find all the war and posturing and characters to be ash and dust and thorn for me, just weariness and work and pain. The moments of greatness within The Iliad do not lift me like many of the classics that sit behind the cultures in which I was raised. Perhaps it is that with every loved one I bury in my life, with every heap of ashes I scatter in the wind or every coffin lowered into the ground and every prayer book incantation I utter, I care less for Homer’s great epic of war and loss.

Neither do I care much for it as a tale of the folly of men and gods. I knew about this already. I see it in myself.

And my Greek is not strong enough to carry me fully into the scents and sounds of this Aegean tale to give me that sense of the heart of a culture. With Greek, I get more of the Mediterranean air from a few lines of Plato or Paul than this Homeric epic.

Thus it was with somewhat of a selfish motive that, when designing a Western literature guided study for a bright, critical student, I shockingly chose not to reread the Iliad with her, but assigned The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller–which I had never read. A bit of a risk, but my student has both good reading skills and sardonic wit. Our conversation can mock or praise as the text leads us, but will, in any case, be thoughtful. And I knew the book to be well-researched and well-written, so I took the risk.

Thus it was with somewhat of a selfish motive that, when designing a Western literature guided study for a bright, critical student, I shockingly chose not to reread the Iliad with her, but assigned The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller–which I had never read. A bit of a risk, but my student has both good reading skills and sardonic wit. Our conversation can mock or praise as the text leads us, but will, in any case, be thoughtful. And I knew the book to be well-researched and well-written, so I took the risk.

I am happy to say that the experiment was a success. My student and I each loved The Song of Achilles is, finding it a fresh reading experience. While The Song of Achilles is a modern psychological novel, it is definitely soaked in research and a love for the literature and the world it came from.

Moreover, Miller is able to capture a mythic voice–a story of depth whose primary narrator is able to be human and near to the action while giving a thorough sense of wonder and distance and greatness that a myth requires. Without losing a compelling personal story, a myth retold should invite us to foundational themes in a world touched by the divine or the fates. In The Song of Achilles, I felt the Aegian culture breathe through the text and experienced Homer’s war epic more dynamically than I had ever done before. I was drawn in more personally to mythic moments of the text, like the dangers of hubris and the power of friendship and the capricious nature of the gods. More than this, Miller’s chosen literary themes danced in the story with vivacity. The temptation to entomb what we love, the love of craft, the inhumanity of human endeavours, the loss of self in greatness, and history’s true measure of a Great One–Miller excells at giving this text its own mythic life. She even succeeded in giving me an Achilles that I think is worth remembering in history.

While Miller’s Song is a complex thematic vision, it is the voice of the novel where she has had her greatest success.

While Miller’s Song is a complex thematic vision, it is the voice of the novel where she has had her greatest success.

Though I hesitate to criticize the great Margaret Atwood, a significant literary voice, it is in the “voice” where she fails with her Penelopiad.

Though I hesitate to criticize the great Margaret Atwood, a significant literary voice, it is in the “voice” where she fails with her Penelopiad.

The Penelopiad is Canadian great Margaret Atwood’s sharp, funny retelling of Homer’s Odyssey from a feminist angle. Indeed, the body of the tale is told from Penelope’s perspective and in her voice–a retelling of the epic of reunion from the perspective of Odysseus’ wise and thoughtful wife. At a deeper level–and I am not sure that most readers realize this about the text–the tale is really from the perspective of the maids murdered in the final hours of Odyssey’s manly show of violent virtue, alternating between Penelope’s afterworldly, non-time-bound perspective and a “chorus” that provides some of the narrative background or prophetic sarcasm.

Margaret Atwood is a pretty funny thinker. As usual, her cutting wit shoots through this story. Unfortunately, the creative potentiality of the “chorus”–exploring many different forms and times and spaces–is more grating than gratifying. Perhaps it has an artistic value I have not seen–and perhaps it is strong in the staged performances–but the poetry there is rarely of the skill of the prose. I recognize that I am writing a minority report here. But with a few strong exceptions, I was relieved to return to Penelope’s voice in the prose chapters.

Margaret Atwood is a pretty funny thinker. As usual, her cutting wit shoots through this story. Unfortunately, the creative potentiality of the “chorus”–exploring many different forms and times and spaces–is more grating than gratifying. Perhaps it has an artistic value I have not seen–and perhaps it is strong in the staged performances–but the poetry there is rarely of the skill of the prose. I recognize that I am writing a minority report here. But with a few strong exceptions, I was relieved to return to Penelope’s voice in the prose chapters.

And, frankly, the deep meaning of the maids comes through in Penelope’s narrative without the moralistic chorus.

This may be a unique text, where Atwood’s sardonic cultural criticism bends the story in a way that keeps the story from living at the front of the reader’s experience.

Perhaps I am simply impatient in the chorus sections. I can recognize this weakness when I read some dramas–an inability to suspend my disbelief and receive the form.

Perhaps I am simply impatient in the chorus sections. I can recognize this weakness when I read some dramas–an inability to suspend my disbelief and receive the form.

Even in the prose parts, however, while Penelope forms in my mind as an individual character of note, and even as her netherworld environment provides a humorous-yet-productive background to the tale, this myth retold is hardly a satisfying one. While it is a provocative feminist rereading of the tale, it lacks the subtle critique and generative world-building of Atwood’s best feminist works or her best dystopias.

And as a return to a Greek tale, it lacks the sheer energy of other rereadings, like Hélène Cixous’ essay, “The Laugh of the Medusa,” or the invitation to the world and text that popular retellings like the Percy Jackson series can provide. The Penelopiad, full of writing skill in a gorgeously designed book, lacks the best cultural criticism that runs through Atwood’s post-apocalyptic and dystopic fiction where she strikes out on her own to remake the world in her own made worlds.

Ultimately, though, it is in the voice where Atwood’s Penelope falls short. When one has read a myth retold like C.S. Lewis‘ Till We Have Faces with Orual’s rich, first-person Greek narrative of self, I simply cannot settle for a mythic voice that does not provide in its tenor what it achieves in its point of view.

Ultimately, though, it is in the voice where Atwood’s Penelope falls short. When one has read a myth retold like C.S. Lewis‘ Till We Have Faces with Orual’s rich, first-person Greek narrative of self, I simply cannot settle for a mythic voice that does not provide in its tenor what it achieves in its point of view.

Madeleine Miller’s Patroclus, as well, is a living, breathing voice of mythic remembrance and new creation: an outcast, uncertain in love, certain in honour and adoration and ethical risk, a character who lives in me as I live in the text.

Atwood’s myth retold is good, but there is a greatness to Lewis’ Till We Have Faces and Miller’s Song of Achilles that provides a pattern-match of content and form that is deeply rewarding for readers (or at least this reader).

Margaret Atwood is a far more mature writer than Madeleine Miller in this her first novel, and a more literary creator than C.S. Lewis, so it is a surprise to see these words on my own screen. Yet, it is in in Till We Have Faces that we see Lewis in his fullest profile as a writer of what we call “literary fiction”–the genre in which Atwood excels even when she challenges its boundaries, and the genre in which Miller writes even despite her popular reach. We see moments in Lewis of this literary possibility in some of the poetry, at points in Perelandra or “The Weight of Glory”–and even an occasional hint in Narnia. Till We Have Faces offers us that full-blooded myth retold in a genre that has brought great richness to the 20th century.

Margaret Atwood is a far more mature writer than Madeleine Miller in this her first novel, and a more literary creator than C.S. Lewis, so it is a surprise to see these words on my own screen. Yet, it is in in Till We Have Faces that we see Lewis in his fullest profile as a writer of what we call “literary fiction”–the genre in which Atwood excels even when she challenges its boundaries, and the genre in which Miller writes even despite her popular reach. We see moments in Lewis of this literary possibility in some of the poetry, at points in Perelandra or “The Weight of Glory”–and even an occasional hint in Narnia. Till We Have Faces offers us that full-blooded myth retold in a genre that has brought great richness to the 20th century.

Indeed, it may be the only novel of Lewis’ seriously studied in the English lit university curriculum a generation from now–if university professors can make the leap past the faux-literary Ypres Salient that puts genre fiction at war with literary fiction.

This is a divide that Atwood often bridges–or, I suppose, a boundary that she chooses to transgress as a lifelong reader of science fiction, myth, and fantasy and a writer of “speculative fiction.” As I am someone who spends most of his reading time digging through the reject bin of the lit fic gatekeepers, it is a line I am pleased to see blurred by many of my favourite contemporary women writers beyond Atwood, like Nalo Hopkinson, N.K. Jemisin, Nnedi Okorafor, and (having recently set down their pens) Octavia Butler and Ursula K. Le Guin. If the stories of gods and miracles are also speculative, Madeleine Miller bridges these worlds well in The Song of Achilles.

This is a divide that Atwood often bridges–or, I suppose, a boundary that she chooses to transgress as a lifelong reader of science fiction, myth, and fantasy and a writer of “speculative fiction.” As I am someone who spends most of his reading time digging through the reject bin of the lit fic gatekeepers, it is a line I am pleased to see blurred by many of my favourite contemporary women writers beyond Atwood, like Nalo Hopkinson, N.K. Jemisin, Nnedi Okorafor, and (having recently set down their pens) Octavia Butler and Ursula K. Le Guin. If the stories of gods and miracles are also speculative, Madeleine Miller bridges these worlds well in The Song of Achilles.

Miller’s Song no doubt has imperfections. I was hopeful for a great epic of friendship that is unusual outside of YA literature today–and C.S. Lewis demonstrates in The Four Loves that friendship is a storyline worthy of great treatment (and I wonder if there is a little nod to Lewis’ Narniad in our first meeting of Chiron, the centaur-teacher). Instead, Miller follows Plato’s supposition that Patroclus and Achilles were lovers. Miller does it to grand and troublesome (in an intriguing way) effect, and there is still much to enjoy about the adventure of friendship in this story of love and war. Still, I am looking for something more than romance in our stories for today–though I suppose I might be writing another minority report.

Miller’s Song no doubt has imperfections. I was hopeful for a great epic of friendship that is unusual outside of YA literature today–and C.S. Lewis demonstrates in The Four Loves that friendship is a storyline worthy of great treatment (and I wonder if there is a little nod to Lewis’ Narniad in our first meeting of Chiron, the centaur-teacher). Instead, Miller follows Plato’s supposition that Patroclus and Achilles were lovers. Miller does it to grand and troublesome (in an intriguing way) effect, and there is still much to enjoy about the adventure of friendship in this story of love and war. Still, I am looking for something more than romance in our stories for today–though I suppose I might be writing another minority report.

Fortunately, as a myth retold, The Song of Achilles is greater than romance–as it is greater than war or culture or parable or even the legend of legends at the heart of the tale. It is a myth retold, and sits with Till We Have Faces and against The Penelopiad as a model for myth retellers today.

Neil Gaiman is a jerk.

Neil Gaiman is a jerk. These morals emerge naturally from the narrative; none of them are forced. Critics of layered stories are missing the point, I think. Anyone reading Harry Potter would be a dangerously narrow reader if they didn’t see the social implications. Yet they read because the Harry Potter books are good literature that are great fun to read. The Graveyard Book is exactly that type of book, on a much smaller scale.

These morals emerge naturally from the narrative; none of them are forced. Critics of layered stories are missing the point, I think. Anyone reading Harry Potter would be a dangerously narrow reader if they didn’t see the social implications. Yet they read because the Harry Potter books are good literature that are great fun to read. The Graveyard Book is exactly that type of book, on a much smaller scale. But these are granular criticisms within a heap of praise. My real complaint is that Neil Gaiman is a jerk. And greedy too. The Graveyard Book won not only the Newbery Medal, but it also won the Carnegie Medal (a first double win, I believe). If that wasn’t enough, Gaiman took home the Hugo and Locus awards. How are other writer’s supposed to build a career when this guy is sitting down to a computer with his elegant premises, whimsical hair, and friendships with amazing illustrators (in this case, Dave McKean)?

But these are granular criticisms within a heap of praise. My real complaint is that Neil Gaiman is a jerk. And greedy too. The Graveyard Book won not only the Newbery Medal, but it also won the Carnegie Medal (a first double win, I believe). If that wasn’t enough, Gaiman took home the Hugo and Locus awards. How are other writer’s supposed to build a career when this guy is sitting down to a computer with his elegant premises, whimsical hair, and friendships with amazing illustrators (in this case, Dave McKean)?

Last December, I was the recipient of a “

Last December, I was the recipient of a “

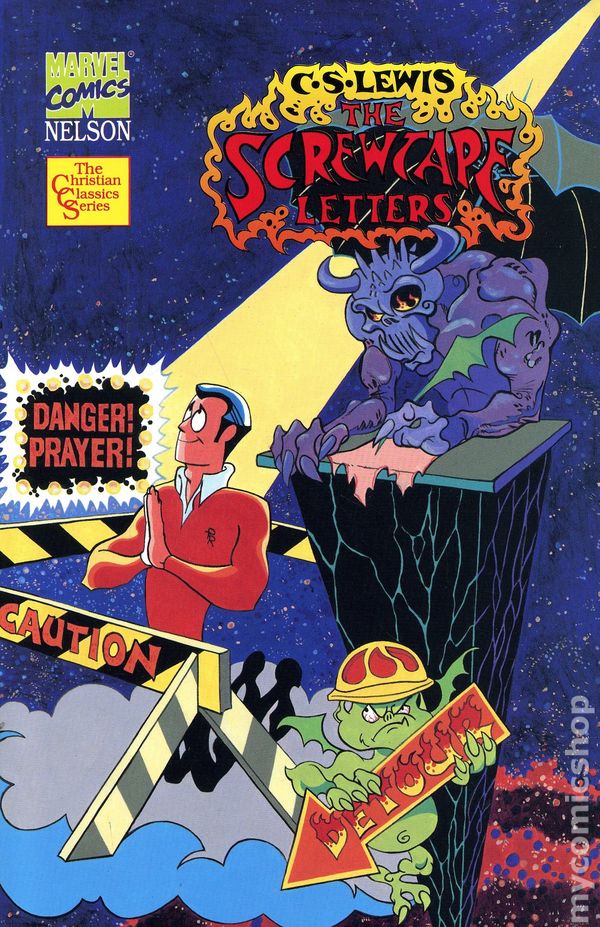

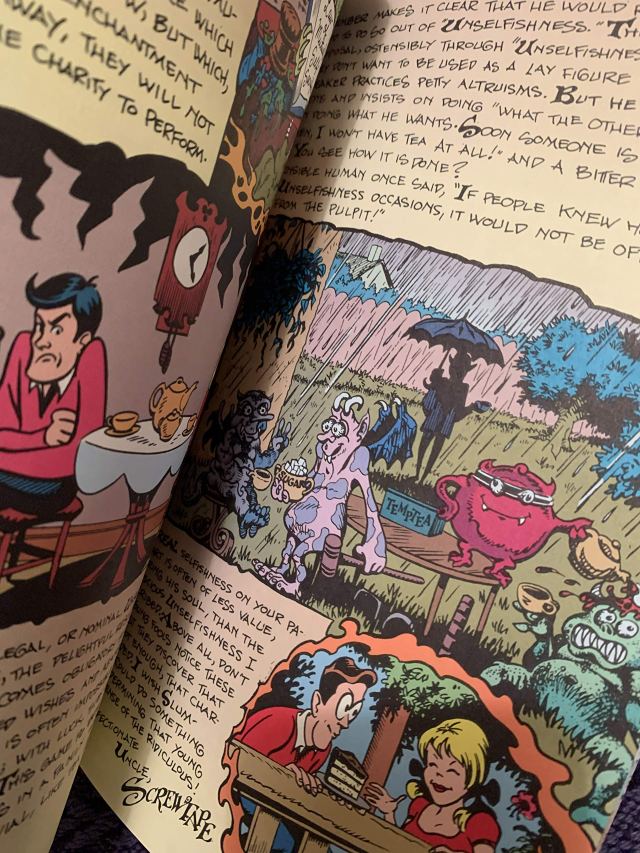

It is a peculiarly strong use of sexism by Lewis to create the double deception of the text: Screwtape’s own self-limitations allow him to be deceived as he is working to deceive humans. As David Mark Purdy and Hsiu-Chin Chou have separately observed**, The Screwtape Letters is not just satire–a single inversion where “up” is “down,” or where the “whites are all blacks” as one of the Screwtape prefaces says. That’s sometimes true and fits the overall genre of the text pretty well.

It is a peculiarly strong use of sexism by Lewis to create the double deception of the text: Screwtape’s own self-limitations allow him to be deceived as he is working to deceive humans. As David Mark Purdy and Hsiu-Chin Chou have separately observed**, The Screwtape Letters is not just satire–a single inversion where “up” is “down,” or where the “whites are all blacks” as one of the Screwtape prefaces says. That’s sometimes true and fits the overall genre of the text pretty well.

Still, This is a pretty cool irony to observe, but I still think the adaptation has merit for fans of C.S. Lewis and comic book lovers.

Still, This is a pretty cool irony to observe, but I still think the adaptation has merit for fans of C.S. Lewis and comic book lovers. ** See David Mark Purdy’s use of “double inversion” in “Red Tights and Red Tape: Satirical Misreadings of The Screwtape Letters,” in Both Sides of the Wardrobe: C.S. Lewis, Theological Imagination, and Everyday Discipleship, ed. Rob Fennell (Eugene, OR: Resource Publications, 2015), 75-84. Not unreasonably as it is clearly satire as a formal genre, Screwtape is commonly categorised as satire in most prefaces and in scholarship; see Filmer, Mask and Mirror, 2, 62, 112, 133; Charles A. Huttar, “The Screwtape Letters as Epistolary Fiction,” Journal of Inklings Studies 6, no. 1 (2016): 91; Raymond M. Potgieter, “Revisiting C.S. Lewis’ Screwtape Letters of 1941 and exploring their relation to ‘Screwtape Proposes a Toast,’” In die Skriflig/In Luce Verbi (2016): 1-8, who suggests parody as a possible genre as well. Coincidental to Purdy’s recategorisation though without quite the detail, Hsiu-Chin Chou’s designation of “double irony” in Screwtape is appropriate; see “The Problem of Faith and the Self: The Interplay between Literary Art, Apologetics and Hermeneutics in C.S. Lewis’s Religious Narratives” (PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, 2008), 205.

** See David Mark Purdy’s use of “double inversion” in “Red Tights and Red Tape: Satirical Misreadings of The Screwtape Letters,” in Both Sides of the Wardrobe: C.S. Lewis, Theological Imagination, and Everyday Discipleship, ed. Rob Fennell (Eugene, OR: Resource Publications, 2015), 75-84. Not unreasonably as it is clearly satire as a formal genre, Screwtape is commonly categorised as satire in most prefaces and in scholarship; see Filmer, Mask and Mirror, 2, 62, 112, 133; Charles A. Huttar, “The Screwtape Letters as Epistolary Fiction,” Journal of Inklings Studies 6, no. 1 (2016): 91; Raymond M. Potgieter, “Revisiting C.S. Lewis’ Screwtape Letters of 1941 and exploring their relation to ‘Screwtape Proposes a Toast,’” In die Skriflig/In Luce Verbi (2016): 1-8, who suggests parody as a possible genre as well. Coincidental to Purdy’s recategorisation though without quite the detail, Hsiu-Chin Chou’s designation of “double irony” in Screwtape is appropriate; see “The Problem of Faith and the Self: The Interplay between Literary Art, Apologetics and Hermeneutics in C.S. Lewis’s Religious Narratives” (PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, 2008), 205.