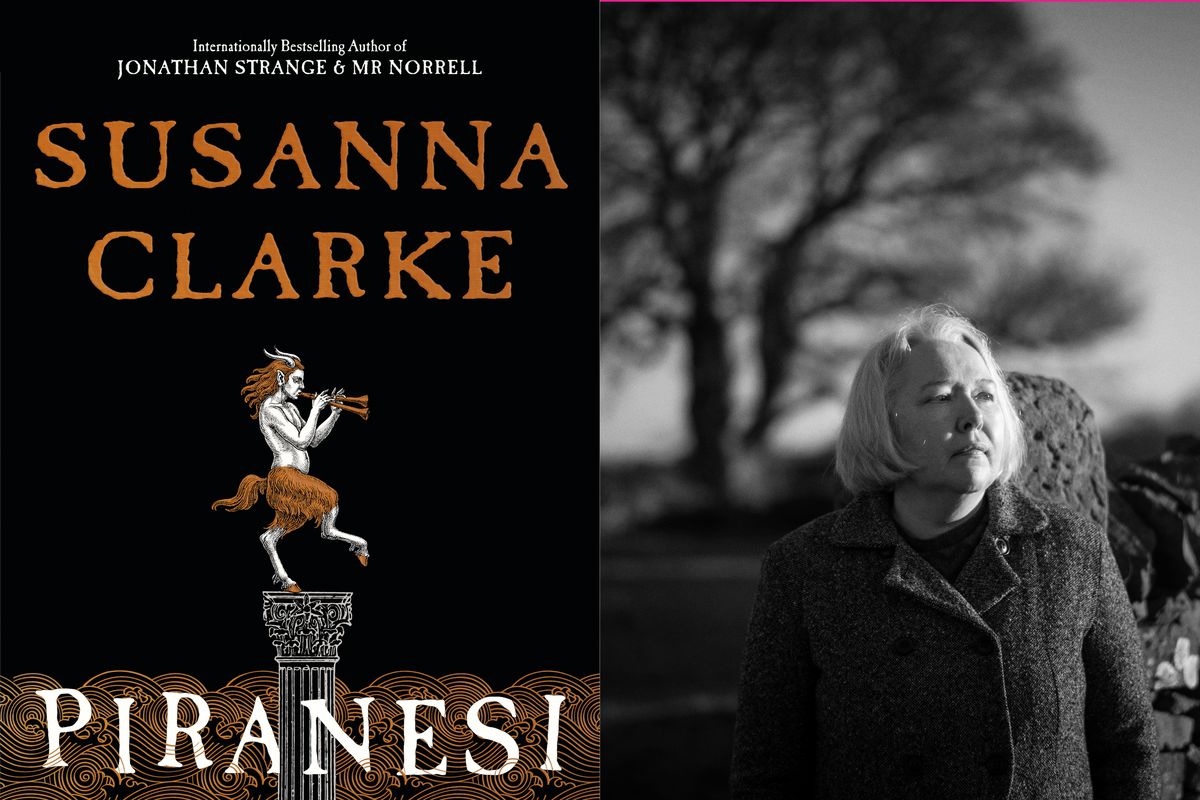

Tamsyn Muir’s Locked Tomb Series is a discovery from my stint as a Hugo Award panellist in 2020 and 2021–the years that Gideon the Ninth (book 1) and Harrow the Ninth (book 2) were nominated. As much as I loved these books–and even though I was defending gorgeous, award-deserving books like Alix E. Harrow’s The Ten Thousand Doors of January and Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi–they did not win the Hugos (though Gideon the Ninth won a few other awards, including the Locus best first novel).

Tamsyn Muir’s Locked Tomb Series is a discovery from my stint as a Hugo Award panellist in 2020 and 2021–the years that Gideon the Ninth (book 1) and Harrow the Ninth (book 2) were nominated. As much as I loved these books–and even though I was defending gorgeous, award-deserving books like Alix E. Harrow’s The Ten Thousand Doors of January and Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi–they did not win the Hugos (though Gideon the Ninth won a few other awards, including the Locus best first novel).

While I can occasionally pick a Hugo winner, it is clear to me that my vision of “Novel of the Year” is often different than that of the Worldcon membership as a whole. I am a wee bit out of step, it seems.

SciFi books have dominated the Hugos through the decades–except, perhaps, during the first decade of this century, where the Harry Potter effect created a shift in focus. As fantasists, Rowling was joined then by folks like George R.R. Martin, Neil Gaiman, and (notably) Susanna Clarke. While I love science fiction as much as fantasy in terms of sheer readerly delight, you have to admit that those fantasy winners are such stellar standouts over the SciFi-winning novels of the period.

Fantasy novels sometimes age better, as well. What I remember of the 2011 list is N.K. Jemisin’s The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms, and not the SciFi novel that won–though Charles Stross’ 2006 AI singularity piece, Accelerando, lives still, when other novels of the period have faded in time. Though admittedly not pop-level books, Mary Doria Russell’s passed-over The Sparrow and her 2001-nominated Children of God may end up becoming science fiction classics.

And I must admit that many of the SciFi-weighted winners–and some of those passed over–have become classics or genre standards, like James Blish‘s A Case of Conscience (1959), Robert A. Heinlein‘s Starship Troopers (1960), Stranger in a Strange Land (1962) and The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress (1967), Walter M. Miller, Jr’s A Canticle for Leibowitz (1961), Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle (1963), Frank Herbert’s Dune (1966), Daniel Keyes’ Flowers for Algernon (nominated in 1967), Roger Zelazny‘s Lord of Light (1968), Ursula K. Le Guin‘s The Left Hand of Darkness (1970) and The Dispossesed (1975), Kurt Vonnegut Jr’s Slaughterhouse-Five (nominated in 1970), Larry Niven‘s Ringworld (1971), Arthur C. Clarke‘s Rendezvous with Rama (1974), William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1985), Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game (1986) and Speaker for the Dead (1987), and so on.

Though I loathe Heinlein’s writing, he is the godfather of the Hugos, a giant in his fairly gigantic field. I love most of the books on this list.

Beyond the classics, which take time to settle in, there are times that I resonate with the Hugo choice picks even though I am a little behind the times. N.K. Jemisin, for example, is clearly one of the science fiction greats of the generation. Time will tell if she will stand with the all-time greats, like H.G. Wells, Robert A. Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, Frank Herbert, Ursula K. Le Guin, Philip K. Dick, or Octavia E. Butler. With her triple Hugo Award-winning Broken Earth series—the only author to have an entire trilogy win, the only author to win three years in a row, and one of only five writers who have three or more best novel wins—Jemisin is already set apart as a generation-leading SF superstar. While I really struggled with her 2021 Hugo-shortlisted The City We Became–you can see Part 1 and Part 2 of my review–I do thint she deserved her Broken Earth triple win in 2016, 2017, and 2018 (with some hesitancy on the 2017 mid-series novel, The Obelisk Gate).

Women have been dominating the Hugo Novel category since 2016, and completely filled the shortlist of 2020 and 2021 (but not 2022). Sadly, my 2020 novel pick, The Ten Thousand Doors of January, did not win–though I think it to be a lovely and provocative work of fantasy that is both fresh and classic.

My 2021 book pick was a bit of an outlier: Susanna Clarke’s long-awaited novel, Piranesi–a work of such joyful simplicity and philosophical complexity that I have yet to complete my review … even a year later. I keep rewriting it. It seems to be a problem.

My 2021 book pick was a bit of an outlier: Susanna Clarke’s long-awaited novel, Piranesi–a work of such joyful simplicity and philosophical complexity that I have yet to complete my review … even a year later. I keep rewriting it. It seems to be a problem.

Though Piranesi is a standalone story–not a novel … a fairy tale? dream vision? parable?–I felt I needed to finally read Clarke’s vivid, game-changing 2004 Regency-era fantasy, Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell as background. It was pretty great. This super long novel was the perfect combination of influences for out-of-the-closet Jane Austen-slash-SF lover like myself. Crossing the genre and literary fiction divide, Strange & Norell was longlisted for the 2004 Man Booker Prize and won the 2005 Hugo Award for Best Novel–as well as the World Fantasy Award, the Locus, and the Mythopoeic Award for Adult Lit. Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell is one of the books that defined the decade of fiction.

Although Piranesi is unusually rich and compelling, except for earning Susanna Clarke the elite 2021 Women’s Prize for Fiction and a well-deserved Audie Award for Chiwetel Ejiofor’s audiobook performance, it did not top the major science fiction and fantasy award lists for which it was shortlisted (BFSA, Nebula, World Fantasy Award, Mythopoeic Fantasy Award, and the Hugo Novel).

Another nominee of 2021, Mary Robinette Kowal’s 2021 Hugo-nominated The Relentless Moon, is not, perhaps, a novel to be remembered in history. However, the first novel in Kowal’s Lady Astronaut Universe, The Calculating Stars, deserved its 2019 Hugo win. While I would not have picked it up based on the book description because it sounded too much like a Netflix-type film with overly beautiful people “making a difference” in a historic moment, The Calculating Stars was for me a refreshing discovery–a classic feeling girl-power SciFi novel with religious and postapocalyptic sympathies in a strong and thoughtful series.

Also from the 2021 nominee list, SciFi writer Martha Wells has been publishing for decades, including a Nebula nomination in 1999 for The Death of the Necromancer and Hugo nominations and wins for novellas and book series. She carefully shaped the Murderbot Diaries series that includes the 2021 nominee, Network Effect. She also had the entire series nominated in that category.

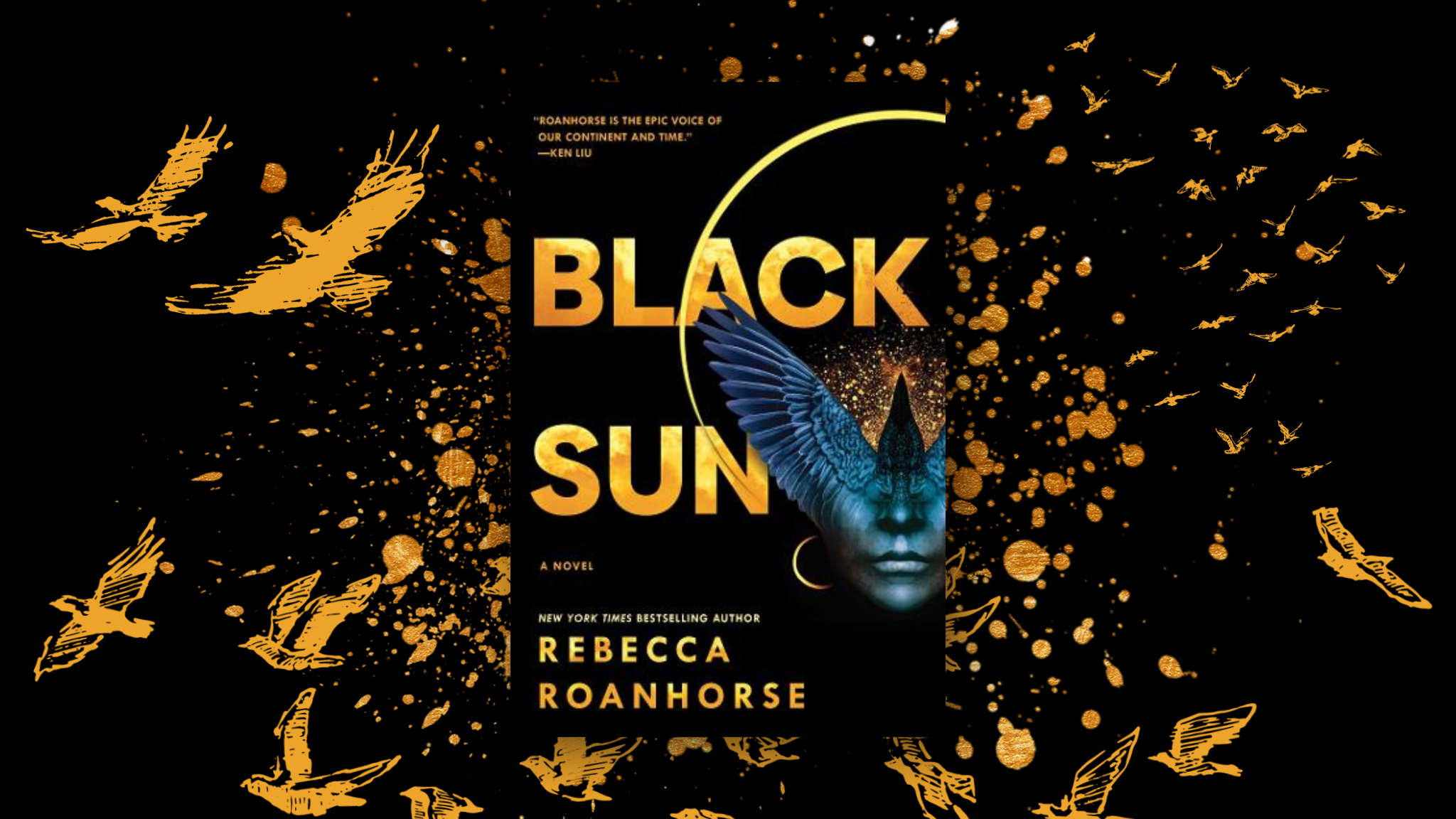

But this is where I start to pull away from the SF fan moment. While I was able to enjoy Network Effect–and my review essay, “Sarcastabots, The Wall-E Effect, and Finding the Human in Martha Wells’ Network Effect,” is one of the better things I’ve written in the last year or so–I am astounded that it took the Hugo over Piranesi or Rebecca Roanhorse’s astonishing mythological novel, Black Sun.

Seriously, check out my thoughts on Black Sun, because Roanhorse’s mythic fantasy is worthy of its Hugo class.

I don’t think Network Effect was either the best or the most long-lasting of the novels. I must admit, though, that it was tough to see Tamsyn Muir’s work get passed over again.

I don’t think Network Effect was either the best or the most long-lasting of the novels. I must admit, though, that it was tough to see Tamsyn Muir’s work get passed over again.

Which brings me to the point of writing today: I sat down to write about the Heroic and Harrowing Features of Tamsyn Muir’s Newest Necromantic Dream Vision, Nona the Ninth, which I loved and found challenging and gorgeous and perverse and troubling. However, I have run out of time for the review itself–and not just because it is a supremely difficult book to review! But partly that.

So, until I have the time or courage to write my response to Nona the Ninth, I hope you enjoyed my thoughts on the Hugo Awards. While favouring the science fiction side of the speculative seating arrangement, the Hugos have been able to predict future SF classics and discern some of the best of the 21st-century turn to fantasy. While I almost never pick the right winner, the Hugos continually give me a rich reading list that includes some of the best–and some of the very good–works of the generation.

So, until I have the time or courage to write my response to Nona the Ninth, I hope you enjoyed my thoughts on the Hugo Awards. While favouring the science fiction side of the speculative seating arrangement, the Hugos have been able to predict future SF classics and discern some of the best of the 21st-century turn to fantasy. While I almost never pick the right winner, the Hugos continually give me a rich reading list that includes some of the best–and some of the very good–works of the generation.

And, classically, I am already behind! There are 6 SF-heavy 2022 Hugo best novel nominees who have been in the world for months, and I haven’t read a single one.

- A Desolation Called Peace, by Arkady Martine (Tor)

- The Galaxy, and the Ground Within, by Becky Chambers (Harper Voyager / Hodder & Stoughton)

- Light From Uncommon Stars, by Ryka Aoki (Tor / St Martin’s Press)

- A Master of Djinn, by P. Djèlí Clark (Tordotcom / Orbit UK)

- Project Hail Mary, by Andy Weir (Ballantine / Del Rey)

- She Who Became the Sun, by Shelley Parker-Chan (Tor / Mantle)

I guess that’s my Hugo Christmas wish list!