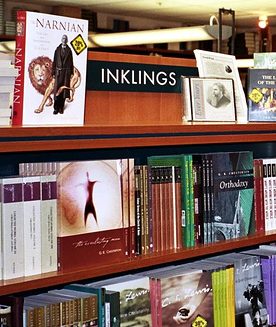

Dorothy L. Sayers has fallen into my life–and I into hers–because of my gloriously irresponsible definition of the Inklings. With a lifelong interest in J.R.R. Tolkien, and a growing curiosity about C.S. Lewis, I was thrilled to discover an entire shelf dedicated to “The Inklings” at the Regent College Bookstore. Regent College in Vancouver where I chose to study sacred literature and spiritual theology at a graduate level. Regent was where I had the innocent audacity to treat St. Paul’s letters like fictional worlds in my thesis, beginning my real path to becoming a Theologian of Literature, or Literary Theologian, or whatever we might want to call it.

Dorothy L. Sayers has fallen into my life–and I into hers–because of my gloriously irresponsible definition of the Inklings. With a lifelong interest in J.R.R. Tolkien, and a growing curiosity about C.S. Lewis, I was thrilled to discover an entire shelf dedicated to “The Inklings” at the Regent College Bookstore. Regent College in Vancouver where I chose to study sacred literature and spiritual theology at a graduate level. Regent was where I had the innocent audacity to treat St. Paul’s letters like fictional worlds in my thesis, beginning my real path to becoming a Theologian of Literature, or Literary Theologian, or whatever we might want to call it.

The Regent College Bookstore is an admirable species of its kind. It also, I believe, has a somewhat promiscuous definition of the Inklings. I have no doubt that G.K. Chesterton was in that section–and if George MacDonald was not there, he was nearby.

The Regent College Bookstore is an admirable species of its kind. It also, I believe, has a somewhat promiscuous definition of the Inklings. I have no doubt that G.K. Chesterton was in that section–and if George MacDonald was not there, he was nearby.

The Bookstore had everything Lewis-related one could imagine, as any local bookstore of its kind would. However, it also included the philosopher-poet novelist Charles Williams–no doubt because philosopher-poet professor Loren Wilkinson is one of the few folks brave enough to offer an entire graduate-level class on Charles Williams‘ theology. Before Amazon and print-on-demand gave us access to obscure and out-of-print works, the Regent College press released many of Williams’ novels and plays, as well as his theological study, The Descent of the Dove. Though I had not yet met Owen Barfield at Regent–the First and Last Inkling, and the figure who most continuously enlightens and endarkens my study of Lewis and Tolkien and literary theory–I have no doubt the bookstore had Barfield’s most important work.

Besides the Fantastic Four–Lewis, Tolkien, Williams, and Barfield–extending my reading into the larger literary alliance of the Inklings has been valuable to me. I have explored Christopher Tolkien‘s work as a literary scholar and (of course) Middle-earth editor. Warren Lewis–Jack’s big brother–is a surprisingly clear and thoughtful writer in his diaries and his French histories, like The Splendid Century. Nevill Coghill has enriched my reading of Chaucer, and Hugo Dyson supplies one of the most quotable and least fully-quoted Inklings quotations that is likely to be apocryphal.

Besides the Fantastic Four–Lewis, Tolkien, Williams, and Barfield–extending my reading into the larger literary alliance of the Inklings has been valuable to me. I have explored Christopher Tolkien‘s work as a literary scholar and (of course) Middle-earth editor. Warren Lewis–Jack’s big brother–is a surprisingly clear and thoughtful writer in his diaries and his French histories, like The Splendid Century. Nevill Coghill has enriched my reading of Chaucer, and Hugo Dyson supplies one of the most quotable and least fully-quoted Inklings quotations that is likely to be apocryphal.

Chesterton and MacDonald are among the roots of Tolkien and Lewis’ literary mountains, to use Douglas Anderson’s phrase. So I have followed Regent’s lead–as well as the framework of the Seven Wade authors from the Wheaton archive–in allowing myself to be enriched by what I call the Honourary Inklings. One of these Honourary Inklings is a Dorothy L. Sayers–a Regent Bookstore Inkling betimes, a Wade author, and one of the transmedial intellectual-populist “Oxford Christians” of the Inklings generation.

Given the popularity of the Lord Peter Wimsey mystery novels and successive film, radio, and television adaptations, there is no doubt that Sayers would have been known in her generation as a novelist. Sayers was one of the Queens of Crime, and a founding member (with Chesterton) of The Detection Club–formed in 1930 as a ragtag group of UK mystery writers and still meeting today.

Given the popularity of the Lord Peter Wimsey mystery novels and successive film, radio, and television adaptations, there is no doubt that Sayers would have been known in her generation as a novelist. Sayers was one of the Queens of Crime, and a founding member (with Chesterton) of The Detection Club–formed in 1930 as a ragtag group of UK mystery writers and still meeting today.

Previously, though–and most centrally, I believe–Sayers was a poet. Later, Sayers the playwright would have been considered for her WWII BBC radio passion play, The Man Born to Be King, as well as other notable plays (such as “The Just Vengence,” 1946). Or she may have been considered for her theological reflections and influential essays like “Are Women Human?” And then, almost by surprise, a fifth motif in Sayers’ literary score is her translation of Dante‘s Divine Comedy, published by Penguin as Hell (1949), Purgatory (1955,) and Paradise (1962, completed by Barbara Reynolds).

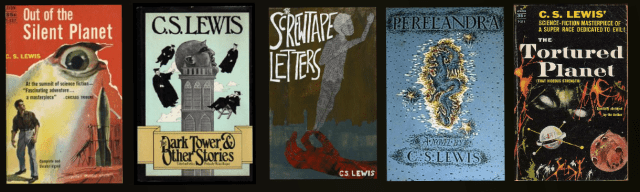

My own discovery of Sayers is an unusual literary journey. My first encounter with her writing was in her letters. I was surprised by the sudden bright energy of Lewis’ letters to Sayers, and so I turned to Sayers’ letter collection (by Barbara Reynolds) to fill out my reading. Though I sense that Sayers’ letters to Lewis are a bit guarded, they are blunt, personal, thoughtful, and ironic. Sayers’ demonical response to Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters is clever and endearing. “The Sluckdrib Letter” is uniquely self-deprecating, as Sluckdrib is the demon assigned to Sayers herself. The letter artfully offers a reflection on the spiritual complexities of the writing life (you can read the entire Sluckrib Letter with my commentary here).

My own discovery of Sayers is an unusual literary journey. My first encounter with her writing was in her letters. I was surprised by the sudden bright energy of Lewis’ letters to Sayers, and so I turned to Sayers’ letter collection (by Barbara Reynolds) to fill out my reading. Though I sense that Sayers’ letters to Lewis are a bit guarded, they are blunt, personal, thoughtful, and ironic. Sayers’ demonical response to Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters is clever and endearing. “The Sluckdrib Letter” is uniquely self-deprecating, as Sluckdrib is the demon assigned to Sayers herself. The letter artfully offers a reflection on the spiritual complexities of the writing life (you can read the entire Sluckrib Letter with my commentary here).

Following the Lewis-Sayers letters, I read The Man Born to be King in book form (I later listened to a BBC production), and I agree with the Lewis brothers that it works as Lenten or Eastertide reading. Also from WWII, Sayers’ The Mind of the Maker (1941) is, I believe, one of the more important works in my theological understanding of creativity and vocation.

I then began hopscotching through Sayers’ essays, including Sayers’ long contribution on Dante to the paperback Inklings colloquium edited by C.S. Lewis, Essays Presented to Charles Williams (which included formative essays like Tolkien’s “On Fairy-stories,” C.S. Lewis’ “On Stories,” and Warren Lewis‘ first historical work). From Sayers’ tribute to Williams and Dante, I began working slowly through her translations of The Divine Comedy. Sayers’ attempt to preserve Dante’s original Italian terza rima rhyme structure in English makes for a refreshing reading of the Comedy. However, for me as an amateur, Sayers’ most helpful work is her commentary and resource guide for each book and each Canto–“supplementary” notes that make up more than half of each volume. I would love someday to have an interactive version of Sayers’ Dante, with a dramatized reading of the text, visualizations of the notes, and nicely designed maps and reading guides based on Sayers’ notes.

I then began hopscotching through Sayers’ essays, including Sayers’ long contribution on Dante to the paperback Inklings colloquium edited by C.S. Lewis, Essays Presented to Charles Williams (which included formative essays like Tolkien’s “On Fairy-stories,” C.S. Lewis’ “On Stories,” and Warren Lewis‘ first historical work). From Sayers’ tribute to Williams and Dante, I began working slowly through her translations of The Divine Comedy. Sayers’ attempt to preserve Dante’s original Italian terza rima rhyme structure in English makes for a refreshing reading of the Comedy. However, for me as an amateur, Sayers’ most helpful work is her commentary and resource guide for each book and each Canto–“supplementary” notes that make up more than half of each volume. I would love someday to have an interactive version of Sayers’ Dante, with a dramatized reading of the text, visualizations of the notes, and nicely designed maps and reading guides based on Sayers’ notes.

It was only then, having found Sayers through letters, theological and literary reflection, and translation, that I turned to Lord Peter Wimsey. Almost all of the mystery fiction I have enjoyed comes from the Golden Age of Detective Fiction–Agatha Christie and G.K. Chesterton, in particular–and the Sherlocks before, within, and after the Golden Age. So while I can offer very little critical judgement of the Lord Peter Wimsey novels as a specimen of the genre, I can give a brief response from my growing sense of Sayers the writer.

And Whose Body? is where it all began in the early 1920s, not long after Sayers received her MA–5 years after she had received first-class honours for doing the work at Somerville College, Oxford. Sayers had published poetry and worked in education, publishing, and advertising, and found herself writing a bit of detective fiction.

And Whose Body? is where it all began in the early 1920s, not long after Sayers received her MA–5 years after she had received first-class honours for doing the work at Somerville College, Oxford. Sayers had published poetry and worked in education, publishing, and advertising, and found herself writing a bit of detective fiction.

Whose Body? is lovely to read. Lord Peter Wimsey is a deeply ironic nobleman who has an awkwardly affable relationship with English aristocratic life and who has begun amateur sleuthing to stimulate his mind and fill his hours. Whose Body? begins when Lord Peter, by some coincidence, catches wind of a murder. A hilariously daft architect has found a dead man in his bath wearing nothing but a pair of pince-nez. Within hours of the discovery, Inspector Sugg–a police detective deeply committed to following false presumptions to their logical conclusion–has arrested two innocent people (hoping that one of them might be the murderer) and sent the wife of a missing Sir Reuben Levy into despair by falsely identifying the body as his. As the weight of police incompetence has further obscured the paucity of evidence, Lord Peter is recruited as a resource for solving the crime.

Like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, Lord Peter Wimsey has an uncommon intellectual gift for observation and logic. Wimsey, though, has Watsons everywhere in Whose Body? Chief of these is Mervyn Bunter, Lord Peter’s “man,” a butler who keeps Wimsey shaved and in suits and stumbling on the next piece of evidence. Mr. Bunter is intensely competent, cooly sarcastic, and able to anticipate Lord Peter’s personal needs and legal curiosities. Bunter is a photographer, and thus supplies some of the scientific basis for Wimsey’s work, and opens their investigations up to other levels of society.

Like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, Lord Peter Wimsey has an uncommon intellectual gift for observation and logic. Wimsey, though, has Watsons everywhere in Whose Body? Chief of these is Mervyn Bunter, Lord Peter’s “man,” a butler who keeps Wimsey shaved and in suits and stumbling on the next piece of evidence. Mr. Bunter is intensely competent, cooly sarcastic, and able to anticipate Lord Peter’s personal needs and legal curiosities. Bunter is a photographer, and thus supplies some of the scientific basis for Wimsey’s work, and opens their investigations up to other levels of society.

Mr. Bunter is the chief Watson, but Lord Peter collects these people.

Mr. Bunter is the chief Watson, but Lord Peter collects these people.

Scotland Yard Inspector Charles Parker is a true partner in crime detection: a competent and thoughtful policeman who is friendly enough with Lord Peter to trust him, but distant enough to provide counterpoints and other perspectives as they talk through the case.

Lord Peter’s mother, Dowager Duchess of Denver Honoria Lucasta Delagardie, provides cunningly accidental support–“The Duchess was always of the greatest assistance to his hobby of criminal investigation, though she never alluded to it, and maintained a polite fiction of its non-existence” (ch. 1)–however, discretion is not her first line.

And whether they know it or not, Wimsey is able to use experts as his Watsons, like the neurologist Sir Julian Freke or medical student Mr. Piggott. Lord Peter is even able to use Inspector Sugg’s reliable incompetence to sift the evidence.

Beyond Lord Peter’s success in using all of these Golden Age collaborators, he is by temperament patient, generous with port, distrustful, a lover of fiction, deeply intuitive, and thrilled by the adventure. He also suffers from PTSD, or shell shock, from his experience in WWI. Despite his high-profile position and trust in his own critical intelligence, Lord Peter does not invest his suffering with shame, but invites his various kinds of Watsons into this weakness.

Beyond Lord Peter’s success in using all of these Golden Age collaborators, he is by temperament patient, generous with port, distrustful, a lover of fiction, deeply intuitive, and thrilled by the adventure. He also suffers from PTSD, or shell shock, from his experience in WWI. Despite his high-profile position and trust in his own critical intelligence, Lord Peter does not invest his suffering with shame, but invites his various kinds of Watsons into this weakness.

And although “Lord Peter Wimsey was not a young man who habitually took himself very seriously,” he discovers in himself a deeply rooted moral centre that goes beyond social expectation, evolutionary design, and personal instinct–though I am not certain he has understood the full nature of his self-awakening in Whose Body?

Sayers the author, though, recognizes Lord Peter’s conversion of the soul, even if no one in the story does. This moment of crisis between Lord Peter and Inspector Parker shows all Wimsey’s moral character: weariness in the weight of suffering, a commitment to goodness and truth, the desire to see himself truly, and his sardonic sense of humour:

Sayers the author, though, recognizes Lord Peter’s conversion of the soul, even if no one in the story does. This moment of crisis between Lord Peter and Inspector Parker shows all Wimsey’s moral character: weariness in the weight of suffering, a commitment to goodness and truth, the desire to see himself truly, and his sardonic sense of humour:

“Look here, Wimsey,” said Inspector Parker, “do you think he has murdered Levy?”

“Well, he may have.”

“But do you think he has?”

“I don’t want to think so.”

“Because he has taken a fancy to you?”

“Well, that biases me, of course—”

“I daresay it’s quite a legitimate bias. You don’t think a callous murderer would be likely to take a fancy to you?”

“Well—besides, I’ve taken rather a fancy to him.”

“I daresay that’s quite legitimate, too. You’ve observed him and made a subconscious deduction from your observations, and the result is, you don’t think he did it. Well, why not? You’re entitled to take that into account.”

“But perhaps I’m wrong and he did do it,” Lord Peter admitted.

“Then why let your vainglorious conceit in your own power of estimating character stand in the way of unmasking the singularly cold-blooded murder of an innocent and lovable man?”

“I know—but I don’t feel I’m playing the game somehow.”

“Look here, Peter,” said the other with some earnestness, “suppose you get this playing-fields-of-Eton complex out of your system once and for all. There doesn’t seem to be much doubt that something unpleasant has happened to Sir Reuben Levy. Call it murder, to strengthen the argument. If Sir Reuben has been murdered, is it a game? and is it fair to treat it as a game?”

“That’s what I’m ashamed of, really,” said Lord Peter. “It is a game to me, to begin with, and I go on cheerfully, and then I suddenly see that somebody is going to be hurt, and I want to get out of it.”

“Yes, yes, I know,” said the detective, “but that’s because you’re thinking about your attitude. You want to be consistent, you want to look pretty, you want to swagger debonairly through a comedy of puppets or else to stalk magnificently through a tragedy of human sorrows and things. But that’s childish. If you’ve any duty to society in the way of finding out the truth about murders, you must do it in any attitude that comes handy. You want to be elegant and detached? That’s all right, if you find the truth out that way, but it hasn’t any value in itself, you know. You want to look dignified and consistent—what’s that got to do with it? You want to hunt down a murderer for the sport of the thing and then shake hands with him and say, ‘Well played—hard luck—you shall have your revenge tomorrow!’ Well, you can’t do it like that. Life’s not a football match. You want to be a sportsman. You can’t be a sportsman. You’re a responsible person.”

“I don’t think you ought to read so much theology,” said Lord Peter. “It has a brutalizing influence (ch. 7, with a couple of slight changes)”

Although she never attended an Inklings meeting, Dorothy L. Sayers has become part of my mental collective of British Christian authors who combined intellectual life and popular, genre-defining fiction and contributions to culture.

Although she never attended an Inklings meeting, Dorothy L. Sayers has become part of my mental collective of British Christian authors who combined intellectual life and popular, genre-defining fiction and contributions to culture.

While my path into Sayers’ work was unusual, there is continuity throughout: the artful irony, spiritual curiosity, careful self-depreciation, and literary skill that I detected in her letters are features in all of her writing–including her first detective novel, Whose Body?. Not all of the literary experiments work in this first novel: using letters, interviews, and courtroom testimony is effective, while the occasional interruption of second-person narration feels disconnected to me. And I don’t think that Lord Peter is quite settled as a character.

While my path into Sayers’ work was unusual, there is continuity throughout: the artful irony, spiritual curiosity, careful self-depreciation, and literary skill that I detected in her letters are features in all of her writing–including her first detective novel, Whose Body?. Not all of the literary experiments work in this first novel: using letters, interviews, and courtroom testimony is effective, while the occasional interruption of second-person narration feels disconnected to me. And I don’t think that Lord Peter is quite settled as a character.

However, by whatever path you find your way to the novel, Whose Body? is a delightful book for first-time Sayers readers or long-term Inkling friends.

I believe in open access scholarship. Because of this, since 2011 I have made A Pilgrim in Narnia free with nearly 1,000 posts on faith, fiction, and fantasy. Please consider sharing my work so others can enjoy it.

Texts of the Downfall of Númenor

Texts of the Downfall of Númenor