| January |

| 1 |

Jan 01 |

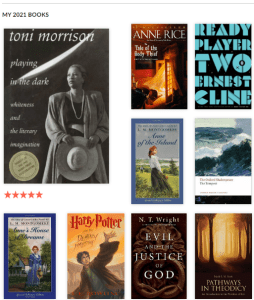

Anne Rice, The Tale of the Body Thief (1992) |

| 2 |

Jan 02 |

Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992) |

| 3 |

Jan 04 |

Selections from Rachel Dodge, The Anne of Green Gables Devotional (2019) |

| 4 |

Jan 11 |

Ernest Cline, Ready Player Two (2020) |

| 5 |

Jan 12 |

L.M. Montgomery, Anne of the Island (1915) |

| 6 |

Jan 15 |

L.M. Montgomery, personal notes from “Fiction Writers on Fiction Writing: Advice, Opinions and a Statement of Their Own Working Methodsby More Than One Hundred Authors” (1923) |

| 7 |

Jan 15 |

Shakespeare, The Tempest (1611) |

| 8 |

Jan 18 |

L.M. Montgomery, Anne’s House of Dreams (1917) |

| 9 |

Jan 18 |

J.K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (2007) |

| 10 |

Jan 18 |

L.M. Montgomery, “Green Gables Letters” to Mr. Weber (1905-09) |

| 11 |

Jan 21 |

N.T. Wright, Evil and the Justice of God (2006) |

| 12 |

Jan 25 |

Melanie J. Fishbane, “’My Pen Shall Heal, Not Hurt’: Writing as Therapy in Rilla of Ingleside andThe Blythes Are Quoted” (2015) |

| 13 |

Jan 25 |

Mark S.M. Scott, Pathways in Theodicy: An Introduction to the Problem of Evil (2015) |

| 14 |

Jan 27 |

L.M. Montgomery, The Alpine Path: The Story of My Career (1917) |

| 15 |

Jan 28 |

Jennifer H. Litster, “The Scotsman, the Scribe, and the Spyglass: Going Back with L.M. Montgomery to Prince Edward Island” (2018) |

| 16 |

Jan 28 |

Carole Gerson, “L.M. Montgomery and the Conflictedness of a Woman Writer” (2008) |

| 17 |

Jan 28 |

Jennifer H. Litster, selections from The Scottish Context of L.M. Montgomery (2000) |

| 18 |

Jan 31 |

Selections from Perry Bacon Jr., Nate Silver, Éric Grenier, Nathaniel Rakich, Geoffrey Skelley, Laura Bronner, Julia Wolfe, Maggie Koerth, Stewart Goetz, Christopher A. Snyder, Maya Angelou, Paul F. Ford, Hildi Froese Tiessen & Paul Gerard Tiessen, Meredith Conroy, Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux and Anna Wiederkehr, Alexander Panetta, Mark S. M. Scott, Maggie Koerth and Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux |

| |

| February |

| 19 |

Feb 01 |

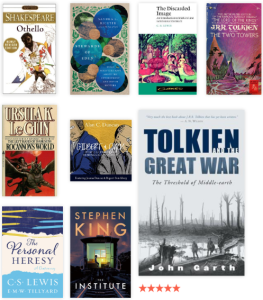

Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice (1596) |

| 20 |

Feb 01 |

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit (1937) |

| 21 |

Feb 03 |

Margaret Steffler, “’Being a Christian’ and a Presbyterian

in Leaskdale” (2015) |

| 22 |

Feb 03 |

Margaret Cavendish, The Blazing World (1666) |

| 23 |

Feb 08 |

Willie James Jennings, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race (2010) |

| 24 |

Feb 11 |

The Brothers Grimm, Household Tales (1812) |

| 25 |

Feb 13 |

C.S. Lewis, The Four Loves broadcast (1958) |

| 26 |

Feb 14 |

Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House (1959) |

| 27 |

Feb 19 |

Tony Dekker, “Planet Narnia: A Book Review” (2010) |

| 28 |

Feb 19 |

L.M. Montgomery, Mary Henley Rubio, Elizabeth Waterston, The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery, Volume III: 1921-1929 (1921-29; 1988; 2014) |

| 29 |

Feb 23 |

Shakespeare, Hamlet (1599-1601) |

| 31 |

Feb 27 |

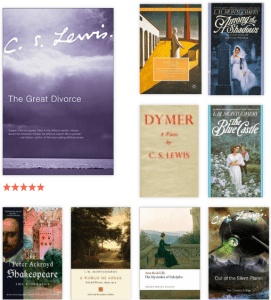

C.S. Lewis, The Great Divorce (1944-45) |

| 32 |

Feb 28 |

Selections from Perry Bacon, Jr., Geoffrey Skelley, Jenny Litster, Julia Azari, Josh Hermsmeyer, Deirdra Dawson, Jane Chance, Tom Holland, Ralph Wood, Alison Millbank, Stephen Yandell, Christopher Garbowski, Amy Amendt-Raduege, Rita Bode, Dani Inkpen, Jess Zimmerman, Elizabeth Iwunwa, Subby Szterszky, C. Christopher Smith, |

| |

| March |

| 33 |

Mar 03 |

Jane Chance, Tolkien, Self and Other: “This Queer Creature” (2016) |

| 34 |

Mar 04 |

Joe Ricke, “The Archangel Fragment: Identifying and Interpreting C. S. Lewis’s ‘Cryptic Note’” (2020) |

| 35 |

Mar 09 |

Ann Radcliffe, The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) |

| 36 |

Mar 11 |

C.S. Lewis, Dymer (1922-6) |

| 37 |

Mar 11 |

L.M. Montgomery, Among the Shadows (1992) |

| 38 |

Mar 15 |

L.M. Montgomery, The Blue Castle (1926) |

| 39 |

Mar 18 |

Peter Ackroyd, Shakespeare: The Biography (2005) |

| 40 |

Mar 20 |

L.M. Montgomery, Benjamin Lefebvre (ed.), A World of Songs: Selected Poems, 1894-1921 (2019) |

| 41 |

Mar 23 |

C.S. Lewis, Out of the Silent Planet (1937) |

| 42 |

Mar 25 |

Shakespeare, The Taming of the Shrew (1593) |

| 43 |

Mar 26 |

L.M. Montgomery, The Watchman & Other Poems (1916) |

| 44 |

Mar 26 |

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring (1954) |

| 45 |

Mar 27 |

Meik Wiking et al., The Little Book of Hygge: The Danish Way to Live Well (2016) |

| 46 |

Mar 31 |

Selections from C.S. Lewis, Perry Bacon Jr., Mary Beth Cavert, Devin Brown, David Downing, Diana Glyer, George Puttenham, Phyllis Tickle, Zoë McLaren, Bonnie Tulloch, Laura Schmidt, Nate Silver, Robert C. Stroud, Katelyn Knox, Karen Kelsky, Carly Cantor, Neil Lewis Jr., Tim & Ann Evans, Bobby Ross, Jr., Scot McKnight, Geoffrey Skelley, |

| |

| April |

| 47 |

Apr 01 |

C.S. Lewis, Perelandra (1942-43) |

| 48 |

Apr 03 |

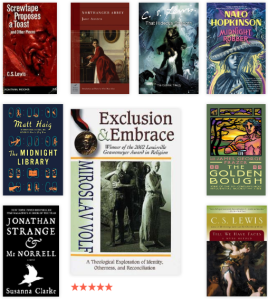

C.S. Lewis, Screwtape Proposes a Toast, and Other Pieces (1941-59; 1965) |

| 49 |

Apr 06 |

Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey (1817) |

| 50 |

Apr 09 |

C.S. Lewis, That Hideous Strength (1943) |

| 51 |

Apr 11 |

Nalo Hopkinson, Midnight Robber (2000) |

| 52 |

Apr 19 |

Matt Haig, The Midnight Library (2020) |

| 53 |

Apr 21 |

Miroslav Volf, Exclusion & Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness, and Reconciliation, revised and updated, plus “Gender” chapter from 1st edition (1996; 2019) |

| 54 |

Apr 23 |

Susanna Clarke, Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell (2004) |

| 55 |

Apr 25 |

James George Frazer, The Golden Bough (1922) |

| 56 |

Apr 27 |

Jim Stockton and Benjamin J.B. Lipscomb, “The Anscombe-Lewis Debate: New Archival Sources Considered” (2021), w. new material from Elizabeth Anscombe and Ludwig Wittgenstein |

| 57 |

Apr 27 |

C.S. Lewis, Till We Have Faces (1954) |

| 58 |

Apr 30 |

Jennifer Cognard-Black, “Lip Service” (2008) |

| 59 |

Apr 30 |

Selections from John Stackhouse, Jr., Jennifer Neyhart, Suzanne Bray, Bruce R. Johnson, James P. Helfers, Gale Watkins, Joel Heck, Stephen Beard, Crystal Hurd, Sarah Waters, Nathaniel Rakich, Perry Bacon, Jr., Steve Mollmann, Dale Nelson, Brian Melton, Devin Brown, Sandra Richter, Kris Swank, David Bratman, Melody Green |

| |

| May |

| 60 |

May 03 |

Sandra L. Richter, Stewards of Eden: What Scripture Says about the Environment and Why It Matters (2020 |

| 61 |

May 06 |

C.S. Lewis, The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature (1964, 1930s-50s Lectures) |

| 62 |

May 11 |

C.S. Lewis, “Screwtape Proposes a Toast” (1959) |

| 63 |

May 13 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, “Inventing a Universe is a Complicated Business” (2016) |

| 64 |

May 14 |

Alan C. Duncan, with Joanna Duncan and Rupert Stutchbury, Gilbert & Jack: What C.S. Lewis Found Reading G.K. Chesterton (2020) |

| 65 |

May 16 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, Rocannon’s World (1966) |

| 66 |

May 18 |

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Two Towers (1954) |

| 67 |

May 19 |

John Garth, Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth (2005) |

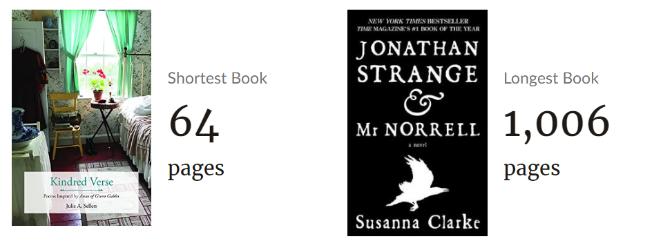

| 68 |

May 20 |

C.S. Lewis and E.M.W. Tillyard, The Personal Heresy (1933-39) |

| 69 |

May 21 |

Heather Walton, selections from Writing Methods in Theological Reflection (2014) |

| 70 |

May 22 |

Stephen King, The Institute (2019) |

| 71 |

May 24 |

Heather Walton, “Introduction” to Literature, Theology and Feminism (2014) |

| 72 |

May 24 |

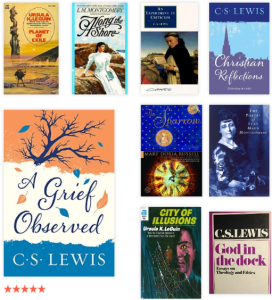

Ursula K. Le Guin, Planet of Exile (1966) |

| 73 |

May 25 |

L.M. Montgomery and Rea Wilmshurst, Along the Shore: Tales by the Sea (1897-1935; 1989) |

| 74 |

May 26 |

C.S. Lewis, An Experiment in Criticism (1960-61) |

| 75 |

May 28 |

C.S. Lewis, A Grief Observed (1960-61) |

| 76 |

May 28 |

C.S. Lewis, Christian Reflections (1939-1963; 1967) |

| 77 |

May 30 |

Mary Doria Russell, The Sparrow (1996) |

| 78 |

May 31 |

Selections by L.M. Montgomery, C.S. Lewis, Russell Perkin, Northrop Frye, Heather Walton, M.D. Aeschliman, Éric Grenier, Dan Hamilton, Gabriel Connor Salter, Steve Hayes, Priscilla Tolkien, Michael J. Gorman, Sam Joeckel, Dawn Llewellyn, Elaine Graham, Pete Ward, Lauren Umstead, Mineko Honda, James P. Helfers, Jerry Root, Verlyn Flieger, Walter Hooper, David J. Leigh, Gi!bert Meilaender, Jeff Wright, Dan DeWitt, Wayne G. Hammond & Christina Scull |

| |

| June |

| 79 |

Jun 01 |

L.M. Montgomery; John Ferns and Kevin McCabe, eds., Poetry of Lucy Maud Montgomery (1893-1933; 1987) |

| 80 |

Jun 02 |

Michael J. Gorman, “Reading Paul Missionally” (2017) |

| 81 |

Jun 03 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, City of Illusions (1967) |

| 82 |

Jun 04 |

C.S. Lewis, God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics (1940-1963; 1971) |

| 83 |

Jun 07 |

L.M. Montgomery, Rainbow Valley (1919) |

| 84 |

Jun 07 |

Don King, “Introduction to The Quest of Bleheris” (Sehnsucht, 2020) |

| 85 |

Jun 07 |

Norbert Feinendegen, selections his philosophical work on C.S. Lewis (2021) |

| 86 |

Jun 08 |

Katharine Sas and Curtis Weyant, “’Ever-Defeated Never Altogether Subdued’: Fighting the Long Defeat in Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and Whedon’s Angel” (2020) |

| 87 |

Jun 08 |

Shakespeare, As You Like It (1599) |

| 88 |

Jun 08 |

Tom Shippey, “Fighting the Long Defeat: Philology in Tolkien’s Life and Fiction” (2002) |

| 89 |

Jun 08 |

Robert Morrison, The Regency Years: During Which Jane Austen Writes, Napoleon Fights, Byron Makes Love, and Britain Becomes Modern (2019) |

| 90 |

Jun 08 |

C.S. Lewis, The Quest of Bleheris, with notes by Don King (1916; 2020) |

| 91 |

Jun 09 |

C.S. Lewis, Spirits in Bondage, with an introduction by Gordon Greenhill (1919; 2017) |

| 92 |

Jun 13 |

L.M. Montgomery, Rilla of Ingleside (1921) |

| 93 |

Jun 14 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) |

| 94 |

Jun 14 |

Shakespeare, Othello (1603) |

| 95 |

Jun 16 |

Edward Said, “Introduction to the Fiftieth-Anniversary Edition of Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature by Erich Auerbach” (1996) |

| 96 |

Jun 16 |

Homer, The Odyssey, translated by Stanley Lombardo, introduction by Sheila Murnaghan (8th c. BCE: 2000) |

| 97 |

Jun 17 |

Erich Auerbach, “Odysseus’ Scar” ch. 1 of Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature (1930s-40s) |

| 98 |

Jun 17 |

Margaret Atwood, The Penelopiad (2005) |

| 99 |

Jun 23 |

Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, PhD, The Dark Fantastic: Race and the Imagination from Harry Potter to the Hunger Games (2020) |

| 100 |

Jun 28 |

Jennifer Cognard-Black, Becoming a Great Essayist (2016) |

| 101 |

Jun 30 |

Jerry Root, David Downing, C.S. Lewis, Miho Nonaka, Jeffry C. Davis, Mark Lewis, Splendour in the Dark: C.S. Lewis’s Dymer in His Life and Work (1922-26; 2020) |

| 102 |

Jun 30 |

Clyde S. Kilby, “Preface” to The Screwtape Letters (1940-42; 1982) |

| 103 |

Jun 30 |

Selections by L.M. Montgomery, C.S. Lewis, Letitia Henville, Louis Markos, S.L. Jensen, Julianne Johnson, Jacob E. Meyer, Rachel M. Roller, J.D. Wunderly, Maya Maley, Daniel Z. Hsieh, Evangeline M. Prior, Marco Giugni, Mary M. Balkun and Susan C. Imbarrato, Jessica Eise, Pat Thomson, Peter Webster, Janet Salmons, T.S. Eliot, Karise Gililland, Dale Nelson |

| July |

| 104 |

Jul 01 |

L.M. Montgomery, The Golden Road (1913) |

| 105 |

Jul 02 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, “Winter’s King” (1969) |

| 106 |

Jul 04 |

C.S. Lewis, Charles Hall (Adapter), Pat Redding (Illustrator), John Kalisz (Illustrator), The Screwtape Letters: Christian Classic Series, Marvel Comics (1941; 1994) |

| 107 |

Jul 05 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Word for World Is Forest (1972) |

| 108 |

Jul 08 |

Crystal Hurd, “An Imaginative Tale from the Father of C.S. Lewis” (2020) |

| 109 |

Jul 08 |

Selections from L.M. Montgomery’s journals, poetry, and novels (1898-1923) |

| 110 |

Jul 12 |

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, Watchmen (1987; 2014; 2020) |

| 111 |

Jul 12 |

Madeline Miller, Song of Achilles (2011) |

| 112 |

Jul 13 |

Maximilian Hart, “The Other Word: Truth and Lies in Le Guin’s Old Speech” (2021) |

| 113 |

Jul 15 |

L.M. Montgomery, Further Chronicles of Avonlea (1904-14; 1920) |

| 114 |

Jul 19 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed (1974) |

| 115 |

Jul 20 |

Shakespeare, King Lear (1605) |

| 116 |

Jul 24 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Wind’s Twelve Quarters (1964-75) |

| 117 |

Jul 26 |

Anonymous, Gilgamesh: A New English Version (18th c. BCE; 2013) |

| 118 |

Jul 26 |

Anonymous, “The Great Hymn to the Aten” and “Enuma Elish” (c. 1350 BCE and 18th c. BCE) |

| 119 |

Jul 26 |

Maximilian Hart, “Draconic Diction: Truth and Lies in

Le Guin’s Old Speech” (2021) |

| 120 |

Jul 28 |

Louise Bernice Halfe, Sky Dancer, Bear Bones and Feathers (1994) |

| 121 |

Jul 28 |

C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (1943) |

| 122 |

Jul 30 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, A Fisherman of the Inland Sea (1994) |

| 123 |

Jul 31 |

Selections from C.S. Lewis, L.M. Montgomery, Hélène Cixous, Monika Hilder, Melanie Fishbane, Ursula K. Le Guin, Stephen King, Daniel P. Jaeckle, Charlotte Spivack, Umberto Eco, Elizabeth Epperly, Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, Harold Bloom, Rebecca Rosenblum, William B. Yeats, Paul Huebener |

| |

| August |

| 124 |

Aug 01 |

Anonymous, “C.S. Lewis: Don vs. Devil” (1947) |

| 125 |

Aug 01 |

Homer, Iliad (8th c. BCE) |

| 126 |

Aug 02 |

Ian Brown, “Virtual churches, real prayers: How COVID-19 is changing the holy seasons” (2021) |

| 127 |

Aug 05 |

Aristophanes, Lysistrata, translated by Jack Lindsay, Sarah Ruden, Alex Struik, et al. (411 BCE) |

| 128 |

Aug 06 |

Plato, Symposium, translated by Tom Griffith, some notes by Jane O’Grady, Tom Griffith (385-370 BCE) |

| 129 |

Aug 06 |

Hesiod, selections from Theogony and Work and Days (c. 700 BCE) |

| 130 |

Aug 06 |

L.M. Montgomery, Emily of New Moon (1923) |

| 131 |

Aug 09 |

Shakespeare, Twelfth Night (1601) |

| 132 |

Aug 10 |

J.R.R. Tolkien, Return of the King (1955) |

| 133 |

Aug 11 |

C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (1943) |

| 134 |

Aug 14 |

Michael Ward, After Humanity: A Guide to C.S. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man (2021) |

| 135 |

Aug 17 |

Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, translated by Rolfe Humphries (mid-1st c. BCE) |

| 136 |

Aug 17 |

Frank Herbert, Dune (1965) |

| 137 |

Aug 18 |

Albert J. Lewis, “The Story of a Half Sovereign,” with notes by Crystal Hurd (1890; 2020) |

| 138 |

Aug 20 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, Four Ways to Forgiveness (1995) |

| 139 |

Aug 24 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Birthday of the World and Other Stories (2002) |

| 140 |

Aug 29 |

Selections from Sørina Higgins’ modernist study (2021) |

| 141 |

Aug 30 |

Virgil, The Aeneid (trans. Fagles; 29-19 BCE) |

| 142 |

Aug 31 |

Selections from C.S. Lewis, L.M. Montgomery, Monika Hilder, Elizabeth Epperly, Jennifer H. Litster, Benjamin Lefebvre, Elizabeth Waterston, A. Wylie Mahon, Dale Nelson, G. Connor Salter, Daniel Whyte IV |

| |

| September |

| 143 |

Sep 01 |

Ovid, Metamorphoses, with an introduction and translation by David Raeburn (8 CE) |

| 144 |

Sep 01 |

Lord Dunsany, ” A Dreamer’s Tale: Poltarnees, Beholder of Ocean” (1910) |

| 145 |

Sep 01 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, “A Citizen of Mondath” (1973) |

| 146 |

Sep 01 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, “World-Making” (1981) |

| 147 |

Sep 01 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, “Imaginary Countries” (1976) |

| 148 |

Sep 07 |

Anne Rice, Memnoch the Devil (1995) |

| 149 |

Sep 08 |

Ray Bradbury, “The Naming of Names, or Dark They Were and Golden-Eyed” (1949) |

| 150 |

Sep 08 |

Cordwainer Smith, “Alpha Ralpha Boulevard” (1961) |

| 151 |

Sep 09 |

Anonymous, Beowulf, translated by Seamus Heaney (8th-11th c. CE) |

| 152 |

Sep 09 |

Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory (3rd ed., 1982; 2007) |

| 153 |

Sep 13 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, “Semley’s Necklace” (1964) |

| 154 |

Sep 13 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Telling (2000) |

| 155 |

Sep 19 |

L.M. Montgomery, Emily of New Moon (1923) |

| 156 |

Sep 21 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Word for World Is Forest (1972) |

| 157 |

Sep 22 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) |

| 158 |

Sep 23 |

L.M. Montgomery, Emily Climbs (1925) |

| 159 |

Sep 25 |

L.M. Montgomery, Emily’s Quest (1927) |

| 160 |

Sep 27 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, “Vaster Than Empires and More Slow” (1971) |

| 161 |

Sep 28 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Lathe of Heaven (1971) |

| 162 |

Sep 29 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed (1974) |

| 163 |

Sep 30 |

Frank Herbert, Dune Messiah (1969) |

| 164 |

Sep 30 |

Selections from C.S. Lewis, L.M. Montgomery, Ursula K. Le Guin, Steve Hayes, Daniel Whyte IV, Jason Smith, Meredith B. McGuire, Anne S. Brown and David D. Hall, Mary McCartin Wearn, Mary Rubio, Catherine Reid, Elizabeth Epperly, Benjamin Lefebvre, Irene Gammel, David D. Hall, Jennifer H. Litster, Andrea McKenzie, Vernon Ramesar, Sam Reimer & Rick Hiemstra, Jane Urquhart, Stephen Winter, Carl McColman, Tom Hillman, David Russell Mosley, Ted Lewis, Samuel Gerald Collins, Andrew Marvell, Charlie W. Starr, Steve Hayes, Yvonne Aburrow, William O’Flaherty, Tyler Huckabee |

| |

| October |

| 165 |

Oct 01 |

Various, Medieval Reading Pack (Julian of Norwich, Margery Kempe, Chaucer, Langland, “Dream of the Rood”, Anselm, etc., 11th-14th c.) |

| 166 |

Oct 05 |

Dante, Hell, trans. Robert Pinsky, foreword by John Freccero, notes by Nicole Pinsky (1308-1320; 1996) |

| 167 |

Oct 06 |

Philip K. Dick, “Exhibit Piece” (1954) |

| 168 |

Oct 06 |

C.S. Lewis, “Dante’s Similes” (1940) |

| 169 |

Oct 06 |

C.S. Lewis, “Imagery in the Last Eleven Cantos of Dante’s Comedy” (1948) |

| 170 |

Oct 06 |

Dante, The Divine Comedy 3: Paradise, translation, notes, and introduction by Dorothy L. Sayers and Barbara Reynolds (1220; 1962) |

| 171 |

Oct 11 |

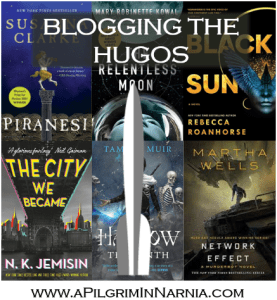

Martha Wells, Network Effect (2020) |

| 172 |

Oct 12 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, A Wizard of Earthsea (1968) |

| 173 |

Oct 13 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Word of Unbinding” (1964) |

| 174 |

Oct 13 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Rule of Names” (1964) |

| 175 |

Oct 16 |

Geoffrey Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales, trans. Burton Raffel; intro. John Miles Foley (1387-1400; 2008) |

| 176 |

Oct 18 |

Mary Robinette Kowal, The Calculating Stars (2018) |

| 177 |

Oct 19 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Tombs of Atuan (1971) |

| 178 |

Oct 26 |

Mary Robinette Kowal, The Fated Sky (2018) |

| 179 |

Oct 27 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Farthest Shore (1972) |

| 180 |

Oct 29 |

Jonathon Lookadoo, “A Preview of the Inklings? A Note on the Early Correspondence of C.S. Lewis and Arthur Greeves” (2018) |

| 181 |

Oct 29 |

Janet Brennan Croft, “The Purest Response of Fantastika to the World Storm,” Introduction to Baptism of Fire: The Birth of the Modern British Fantastic in World War (2015) |

| 182 |

Oct 31 |

Selections from C.S. Lewis, L.M. Montgomery, Joy Davidman, Ursula K. Le Guin, Walter Hooper, Mark S.M. Scott, Jennifer Rogers, Oronzo Cilli, Benjamin Lefebvre, Jane Goodall, Daniel Whyte IV, Katelyn Knox, Jonathan Poletti, Victoria S. Allen, MariJean Wegert, Michael Travers, Jane Hipolito, Colin Manlove, David C. Downing, John Haigh, Joel Heck, James W. Menzies, Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson, Daniel Sutton, Rachel McLay & Howard Ramos, Mary Rubio, William B. Bynum, Elizabeth Millie Joy, Julie M. Dugger, Andrew Cuneo, Don W. King, Stephen Logan, Andrew Krostrom, Brian Melton, Courtney Ellis |

| |

| November |

| 183 |

Nov 01 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, Tehanu (1990) |

| 184 |

Nov 02 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, “Children, Women, Men, and Dragons” (1992) |

| 185 |

Nov 03 |

John M. Bowers, Tolkien’s Lost Chaucer (2019) |

| 186 |

Nov 04 |

Mary Robinette Kowal, The Relentless Moon (2020) |

| 187 |

Nov 07 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, Gifts (Annals of the Western Shore 1, 2004) |

| 188 |

Nov 09 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Other Wind (2001) |

| 189 |

Nov 10 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, “Firelight” (2018) |

| 190 |

Nov 10 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Daughter of Odren” (2014) |

| 191 |

Nov 10 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, Tales from Earthsea (2001) |

| 192 |

Nov 12 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, Voices (Annals of the Western Shore 2, 2006) |

| 193 |

Nov 17 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, Powers (Annals of the Western Shore 3, 2007) |

| 194 |

Nov 18 |

Mark Williams Roche, Selections from Why Choose the Liberal Arts? (2010) |

| 195 |

Nov 21 |

Melanie J. Fishbane, Maud: A Novel Inspired by the Life of L.M. Montgomery (2017) |

| 196 |

Nov 22 |

The Pearl Poet, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (trans. Simon Armitage; late 15th c.; 2007) |

| 197 |

Nov 23 |

Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” (1973) |

| 198 |

Nov 24 |

Kris Swank, “Ursula K. Le Guin: World-builder” (with a lecture by Robert Steed, Signum University, 2021) |

| 199 |

Nov 24 |

Rebecca Roanhorse, Black Sun (2020) |

| 200 |

Nov 30 |

Selections from C.S. Lewis, L.M. Montgomery, Ursula K. Le Guin, Chaucer, Jonathan McGee, Christopher Benson, Juan Siliezar, Fairouz Gaballa, Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson, Mary Rubio, Elizabeth Bishop |

| |

| December |

| 201 |

Dec 01 |

N.K. Jemisin, The City We Became (2020) |

| 202 |

Dec 04 |

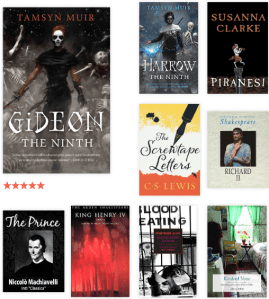

Tamsyn Muir, Gideon The Ninth (2019) |

| 203 |

Dec 11 |

Tamsyn Muir, Harrow The Ninth (2020) |

| 204 |

Dec 14 |

Susanna Clarke, Piranesi (2020) |

| 205 |

Dec 14 |

Shakespeare, Richard II (1595) |

| 206 |

Dec 16 |

Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince, trans. W.K. Marriott (1532) |

| 207 |

Dec 26 |

Shakespeare, Henry IV, Part 1 (1596-97) |

| 208 |

Dec 28 |

Julie A. Sellers, Kindred Verse: Poems Inspired by Anne of Green Gables (2021) |

| 209 |

Dec 31 |

C.S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters (1940-42) |

| 210 |

Dec 31 |

William Lyndsay Gresham, Nightmare Alley (1946) |

| 211 |

Dec 31 |

Selections from C.S. Lewis, L.M. Montgomery, Ursula K. Le Guin, James Deutsch, Robert Browning, James Smoker, Andrea MacKenzie, Benjamin Lefebvre, Malcolm Guite, G. Connor Salter, John Stanifer, Wayne G. Hammond & Christina Scull, David Llewellyn Dodds, Joy Davidman, Abigail Santamaria, Don W. King, Alan M. Wald, William Lindsay Gresham, Liz Rosenberg |

I have finally completed Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra’ The Ingenious Gentleman Sir Quixote of La Mancha. It is my first time completing this classic of Western literature, except for all of those other times I’ve read it.

I have finally completed Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra’ The Ingenious Gentleman Sir Quixote of La Mancha. It is my first time completing this classic of Western literature, except for all of those other times I’ve read it. As I have not read much early modern Spanish with so many archaisms and Castillian influences since my years of captivity by Ottoman corsairs following the Battle of Torpiditolingua, I decided to consult an English translation. Thus, I searched all the known lands of knight-errantry for the best English translation of all the English translations that have ever been made, are being made, or will be made.

As I have not read much early modern Spanish with so many archaisms and Castillian influences since my years of captivity by Ottoman corsairs following the Battle of Torpiditolingua, I decided to consult an English translation. Thus, I searched all the known lands of knight-errantry for the best English translation of all the English translations that have ever been made, are being made, or will be made. Because fortune favours the fortunate, Sancho Panza might have said, but did not, though as Don Quixote did say, “because of my evil sins, or my good fortune,” I found a most beneficent translation of Don Quixote, the recent work of Edith Grossman. Grossman provides breathtaking clarity in her translation, allowing Don Quixote and Sancho Panza and all the rest to live on the page.

Because fortune favours the fortunate, Sancho Panza might have said, but did not, though as Don Quixote did say, “because of my evil sins, or my good fortune,” I found a most beneficent translation of Don Quixote, the recent work of Edith Grossman. Grossman provides breathtaking clarity in her translation, allowing Don Quixote and Sancho Panza and all the rest to live on the page. Granted, it may be as Sancho says, that “hunger is the best sauce in the world,” and I have just fallen for a translation that I happen to like, good or no. I am not inclined to think so, however, for there is no jewel in the world as valuable as a translation that can bring out all of the nuances of a text without mourning what of complexity is lost in translation.

Granted, it may be as Sancho says, that “hunger is the best sauce in the world,” and I have just fallen for a translation that I happen to like, good or no. I am not inclined to think so, however, for there is no jewel in the world as valuable as a translation that can bring out all of the nuances of a text without mourning what of complexity is lost in translation. Observing my cat, Juno, while reading Don Quixote in the winter sunshine, I suddenly understood the Ingenious Gentleman Sir Quixote of La Mancha much better. To ask whether Don Quixote–or a cat–is either wise or insane is the wrong question of this book. Thus lacking all history and being a very poor poet, I endeavoured to capture Don Quixote in verse.

Observing my cat, Juno, while reading Don Quixote in the winter sunshine, I suddenly understood the Ingenious Gentleman Sir Quixote of La Mancha much better. To ask whether Don Quixote–or a cat–is either wise or insane is the wrong question of this book. Thus lacking all history and being a very poor poet, I endeavoured to capture Don Quixote in verse.

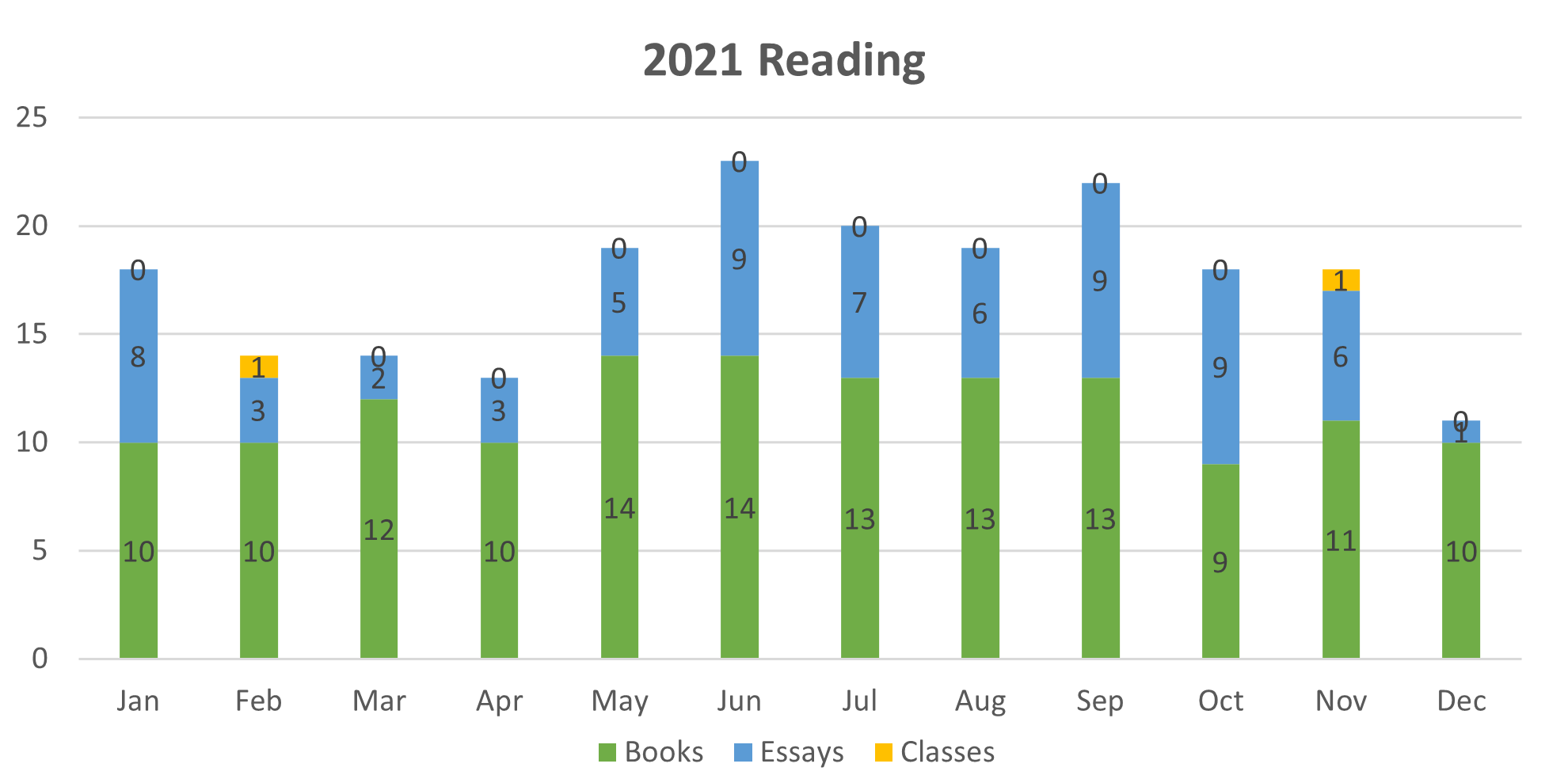

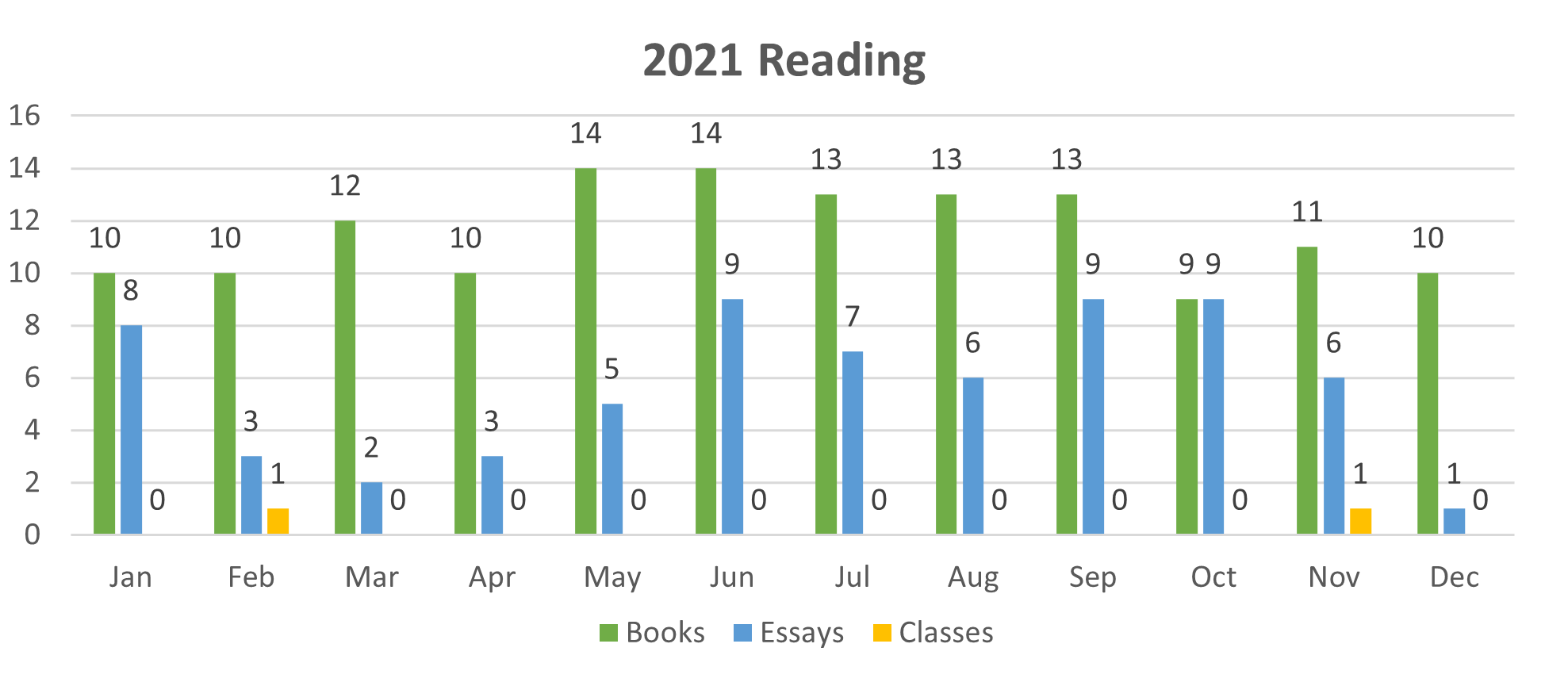

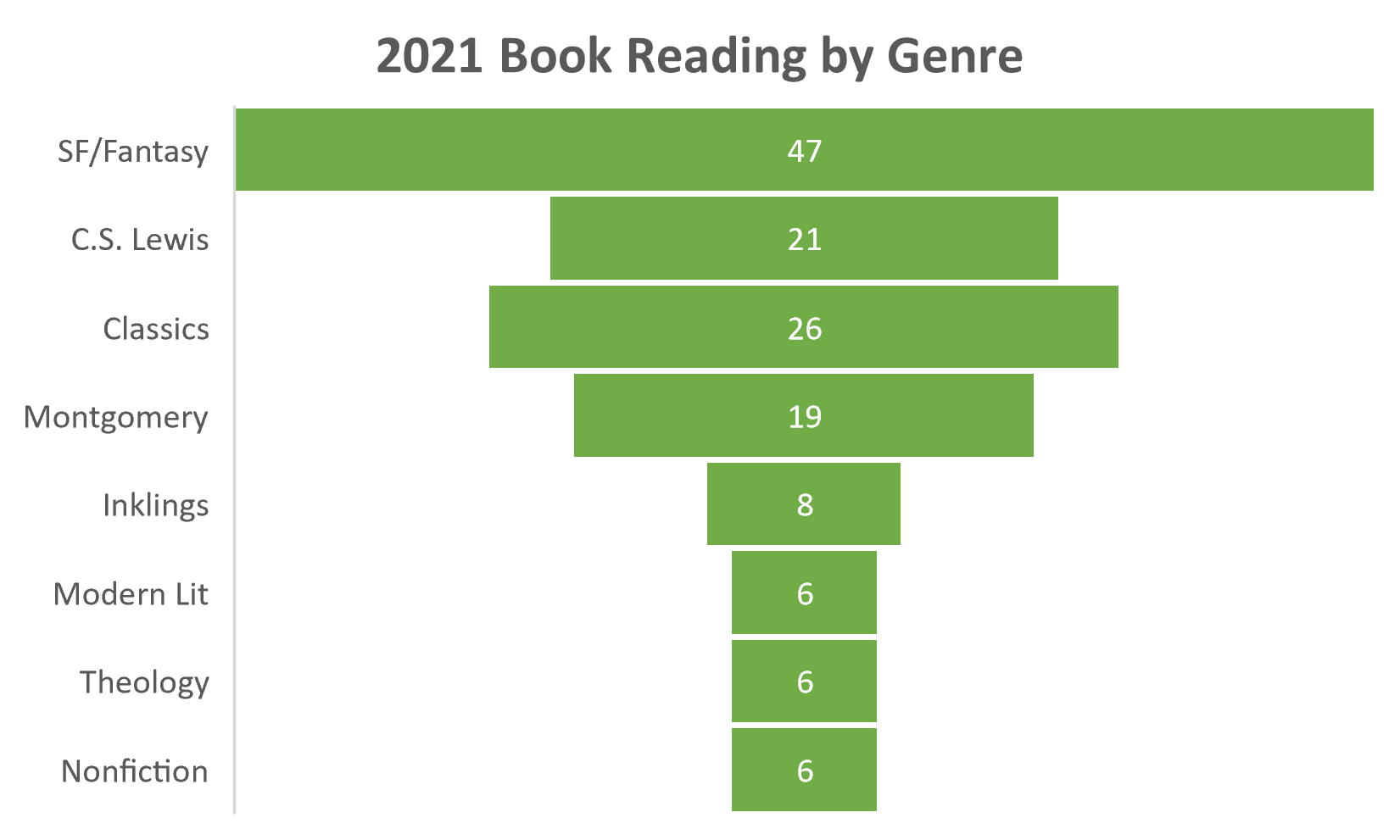

Read 75 articles, shorts stories, essays, or other short pieces

Read 75 articles, shorts stories, essays, or other short pieces