Intertextuality: The Books Inside the Books We Love to Read

Intertextuality: The Books Inside the Books We Love to Read

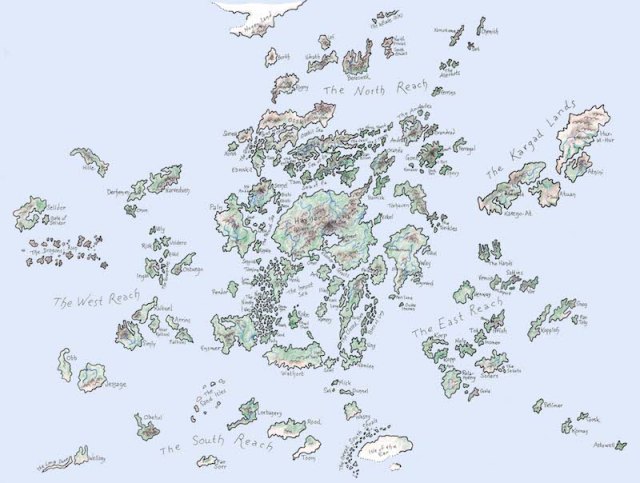

I am very much interested in the books that sit behind the books we read, or the idea of “Intertextuality.” I have tackled this topic before (see the list at the bottom of the page), and my first long peer-reviewed article on C.S. Lewis was offering an intertextual theory of reading Lewis with Lewis (now a chapter in a book edited by Sørina Higgins, The Inklings and King Arthur, which won the Mythopoeic Scholarship Award in Inklings Studies). I spent years writing that chapter, “Mixed Metaphors and Hyperlinked Worlds: A Study of Intertextuality in C.S. Lewis’s Ransom Cycle,” particularly because I find it enriching to see the various layers in a story. Sometimes these stories-behind-the-stories are absolutely essential to understanding our literature: the Hebrew Bible is embedded in the New Testament and Shakespeare takes up the great stories of the West and most of my favourite TV shows make 80s pop culture references. While the story we are reading can work on one level, knowing the stories in the story deepens our experience of reading.

It doesn’t take long reading C.S. Lewis before we find ourselves tugged back to the things he’s read in the quest to discover more about the books we love. After all, what I argue is the most important resource for reading Narnia of our generation, Michael Ward’s Planet Narnia, is really a study of intertextuality. As the best intertextual studies do, Ward goes beyond simply analyzing the allusions and quotations of one text inside of another, but shows how an entire worldview emerges within tales set in an entirely different world. Ward’s query is the right one, I believe, even if I don’t agree with his thesis as a whole. One of the reasons that Narnia is even better for adults is because the magic of The Chronicles of Narnia for readers is that it becomes a richer, more immersive world the more we know of the stories in our Western tradition–and also, I believe, the more we are able to take Narnian lessons and apply to our everyday lives.

It doesn’t take long reading C.S. Lewis before we find ourselves tugged back to the things he’s read in the quest to discover more about the books we love. After all, what I argue is the most important resource for reading Narnia of our generation, Michael Ward’s Planet Narnia, is really a study of intertextuality. As the best intertextual studies do, Ward goes beyond simply analyzing the allusions and quotations of one text inside of another, but shows how an entire worldview emerges within tales set in an entirely different world. Ward’s query is the right one, I believe, even if I don’t agree with his thesis as a whole. One of the reasons that Narnia is even better for adults is because the magic of The Chronicles of Narnia for readers is that it becomes a richer, more immersive world the more we know of the stories in our Western tradition–and also, I believe, the more we are able to take Narnian lessons and apply to our everyday lives.

The Many Links of Lewis and Dante, and a Reading Tool by Marsha Daigle-Williamson

One of those critical authors of the shared past that Lewis keeps bringing into his work is Dante and his Divine Comedy, perhaps the most important Western book of the last 1500 years. As soon as we ask the question about Dante in Lewis’ work, we can begin to see the links. Three of Lewis’ essays in Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature are about Dante, spanning more than twenty-five years of work as a critic. He also discussed Dante in his “Panegyric for Dorothy L. Sayers”—but these are the obvious ones. Most of his work in medieval literature circles around to Dante at some time or another, and Lewis even resorts to the term “Dantesque” at one point. When talking about Milton or Donne or Science Fiction, Lewis finds himself going back to Dante.

Dante was for Lewis the West’s master poet with a genius science fiction mind who wrote the most theologically rich and integrated work of the late Middle Ages. As a literary historian of Medieval and Renaissance literature, Dante was—and remains for researchers after Lewis—an almost unmatched figure.

Dante was for Lewis the West’s master poet with a genius science fiction mind who wrote the most theologically rich and integrated work of the late Middle Ages. As a literary historian of Medieval and Renaissance literature, Dante was—and remains for researchers after Lewis—an almost unmatched figure.

The most critical tool for reading Dante in and with C.S. Lewis so far is the 2015 volume, Reflecting the Eternal: Dante’s Divine Comedy in the Novels of C.S. Lewis by Dr. Marsha Daigle-Williamson. In this late-career major rewriting of her doctoral dissertation, Daigle-Williamson invites readers to imagine the many obvious and subtle links between Dante’s classic text and C.S. Lewis’ fiction.

The most critical tool for reading Dante in and with C.S. Lewis so far is the 2015 volume, Reflecting the Eternal: Dante’s Divine Comedy in the Novels of C.S. Lewis by Dr. Marsha Daigle-Williamson. In this late-career major rewriting of her doctoral dissertation, Daigle-Williamson invites readers to imagine the many obvious and subtle links between Dante’s classic text and C.S. Lewis’ fiction.

A couple of years ago, I published a review essay of Reflecting the Eternal in VII: Journal of the Marion E. Wade Center, which you can find free here. I had always wanted to come back to this long, positive and critical review, and do a bit more thinking about Intertextuality. I heard in the fall that Marsha had passed away. Besides providing this generative study, she was a generous scholar in the way she encouraged others to read well. I hope that in coming back to this book I can provoke some thinking about how we read the books inside of other books and encourage you to look into Marsha Daigle-Williamson’s research.

Because, ultimately, I think that Marsha is right about the many Dante links in Lewis’ writing. In what ways do we find Dante making his way into Lewis’ fiction? The Great Divorce immediately springs to mind as the story most obviously influenced by The Divine Comedy, with its heaven and hell geography and purgatorial principle. The Silver Chair, too, has resonances of Dante’s narrative and sense of space. The Last Battle is about heaven, The Screwtape Letters is about hell, and Till We Have Faces includes a purgatorial last judgement netherworld. As soon as we ask the question we can see a number of hyperlinks back to Dante from Lewis.

Because, ultimately, I think that Marsha is right about the many Dante links in Lewis’ writing. In what ways do we find Dante making his way into Lewis’ fiction? The Great Divorce immediately springs to mind as the story most obviously influenced by The Divine Comedy, with its heaven and hell geography and purgatorial principle. The Silver Chair, too, has resonances of Dante’s narrative and sense of space. The Last Battle is about heaven, The Screwtape Letters is about hell, and Till We Have Faces includes a purgatorial last judgement netherworld. As soon as we ask the question we can see a number of hyperlinks back to Dante from Lewis.

In Reflecting the Eternal, Marsha Daigle-Williamson has most fully answered the question of Dante’s influence upon Lewis’ fiction. In a strong, detailed, book-by-book analysis, Daigle-Williamson gathers together the reading data of each of Lewis’ published long-form fiction works, making every possible link back to The Divine Comedy. So let’s take a look at what she has done before pressing in on her approach a bit.

Description and Evaluation of the Text of Reflecting the Eternal

Reflecting the Eternal takes each of Lewis’ works of published fiction in chronological order, covering Narnia in a single chapter and choosing not to treat Lewis’ poetry or any of his incomplete, posthumously published work. The chapters are each similarly organized, including:

- a two- to four-page summary of Lewis’ work;

- a discussion of that work’s fictional world in conversation with Dante’s imaginative universe;

- a discussion of the journey of the main character(s) and how that pilgrimage has a parallel in The Divine Comedy;

- a consideration of the characters (or objects) in Lewis’ work that fulfill the role of Beatrice to his protagonists; and

- a very brief conclusion.

Though a dense, exegetical, book-by-book detailing of a theme rarely makes good reading—even if it is an ideal way to approach research—the unique features in each chapter provide a great deal of interest.

The most substantial section of each chapter, the journey section, is a line-by-line treatment of all the pertinent quotations, allusions, and echoes of Dante in Lewis’ fiction. Though it might be easiest to get bogged down in this section, this is where many of the “aha!” moments are for me as a reader–and where I will return again and again, using the text as a reader’s guide. The connections to the Ransom Cycle material, for example, provide layer after layer of new meaning for the reader. I was slowly won over to the connection between Dante and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader: in the end, Daigle-Williamson jolted me out of my Homerian rut to provide a whole new way of reading Lewis’ Narnian aquatic travelogue. The result, for me, was not just to see Dante in The Dawn Treader, but to see how all the travel stories are in each other and then find their way into Narnia as well.

The most substantial section of each chapter, the journey section, is a line-by-line treatment of all the pertinent quotations, allusions, and echoes of Dante in Lewis’ fiction. Though it might be easiest to get bogged down in this section, this is where many of the “aha!” moments are for me as a reader–and where I will return again and again, using the text as a reader’s guide. The connections to the Ransom Cycle material, for example, provide layer after layer of new meaning for the reader. I was slowly won over to the connection between Dante and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader: in the end, Daigle-Williamson jolted me out of my Homerian rut to provide a whole new way of reading Lewis’ Narnian aquatic travelogue. The result, for me, was not just to see Dante in The Dawn Treader, but to see how all the travel stories are in each other and then find their way into Narnia as well.

Partly because of the rigour of her analysis and the convincing nature of her thesis, there are moments that Daigle-Williamson pushes her conclusions too far. I did not find the “cardinal sin” analysis in Ransom to be consistent and strong as a whole. Orual’s “blasphemy” in Till We Have Faces is a critical feature of the structure of the book and central to the narrative, so I am not sure the Dantean parallels are exact. Blasphemy is an open-and-shut case for Dante, but in Till We Have Faces it is a more nuanced question of self-delusion and revelation. Is it not right of Orual to resist the gods that she has been presented with—dim and shadowy versions of the true God she cannot see? It is true that her self-imposed and learned blindness limits her vision of divinity, but her complaint against the gods—her blasphemy—ultimately leads her to see the God beyond gods (182-7). Orual’s heresy is reformation, read rightly.

Partly because of the rigour of her analysis and the convincing nature of her thesis, there are moments that Daigle-Williamson pushes her conclusions too far. I did not find the “cardinal sin” analysis in Ransom to be consistent and strong as a whole. Orual’s “blasphemy” in Till We Have Faces is a critical feature of the structure of the book and central to the narrative, so I am not sure the Dantean parallels are exact. Blasphemy is an open-and-shut case for Dante, but in Till We Have Faces it is a more nuanced question of self-delusion and revelation. Is it not right of Orual to resist the gods that she has been presented with—dim and shadowy versions of the true God she cannot see? It is true that her self-imposed and learned blindness limits her vision of divinity, but her complaint against the gods—her blasphemy—ultimately leads her to see the God beyond gods (182-7). Orual’s heresy is reformation, read rightly.

Moreover, as I will argue below, and as Daigle-Williams often intimates in ways that get lost in the data analysis, the critical parallels between Till We Have Faces and the Comedy are textural, not just textual.

Where the treatment of the named sins in Dante and Till We Have Faces might have been stretched, her work on The Great Divorce shows the intimate architectural unity between Lewis’ and Dante’s dreams of the afterlife. While I was not won over by her argument that the George MacDonald character was a “detailed composite of five characters from The Divine Comedy” (137), her inquiry bears interesting fruit and demonstrates well the “continuous, multilayered echoes of Dante’s poem” (137). The division of the ten main narratives of The Great Divorce into two tables—five stories of perverted love and five stories of disordered love—has merit, and works helpfully for teaching the theological novella. Daigle-Williamson’s ultimate argument is that Lewis is tapping in not to Dante’s discussion of the seven cardinal sins, but to his underlying logic of love behind the sins. It is a sophisticated argument worthy of consideration, but it also helps any reader to see Lewis’ stories more in a more intimate way.

Where the treatment of the named sins in Dante and Till We Have Faces might have been stretched, her work on The Great Divorce shows the intimate architectural unity between Lewis’ and Dante’s dreams of the afterlife. While I was not won over by her argument that the George MacDonald character was a “detailed composite of five characters from The Divine Comedy” (137), her inquiry bears interesting fruit and demonstrates well the “continuous, multilayered echoes of Dante’s poem” (137). The division of the ten main narratives of The Great Divorce into two tables—five stories of perverted love and five stories of disordered love—has merit, and works helpfully for teaching the theological novella. Daigle-Williamson’s ultimate argument is that Lewis is tapping in not to Dante’s discussion of the seven cardinal sins, but to his underlying logic of love behind the sins. It is a sophisticated argument worthy of consideration, but it also helps any reader to see Lewis’ stories more in a more intimate way.

Links Beyond the Norm

Added to the unsurpassed detailed analysis of Lewis’ fiction, it is this feature of helping us as readers see the deeper resonances of Dante in Lewis where Reflecting the Eternal is of most critical benefit. Again and again, I was lifted to a new understanding of the rich resource that Dante was to Lewis (and other authors) as Marsha Daigle-Williamson buoyed my understanding of both authors and their fictional worlds much deeper than a word-search or quotation guide could provide.

For example, the question of a Beatrician (or Virgilian) character in each of Lewis’ works is a fascinating one. If not pressed too far, Daigle-Williamson does it very well. Not a slave to her outline, she appropriately splits her chapter on That Hideous Strength into two paths: that of Jane Studdock on the road to St. Anne’s, and that of Mark Studdock on his way into Belbury. As noted by Joe Christopher—a deeply productive Lewis scholar, sometime reader of this blog, and one of Daigle-Williamson’s most important dialogue partners—Ransom is a Beatrician character for Jane. The reader can parallel Jane’s encounter with Ransom in the study with Dante’s encounter with Beatrice in the garden—and consequently see that encounter with Beatrice emerge again and again in Lewis’ fiction. In a dramatic reversal worthy of more critical work, Jane emerges as the Beatrice for Mark, both theologically and as the figural centre of his conversion.

For example, the question of a Beatrician (or Virgilian) character in each of Lewis’ works is a fascinating one. If not pressed too far, Daigle-Williamson does it very well. Not a slave to her outline, she appropriately splits her chapter on That Hideous Strength into two paths: that of Jane Studdock on the road to St. Anne’s, and that of Mark Studdock on his way into Belbury. As noted by Joe Christopher—a deeply productive Lewis scholar, sometime reader of this blog, and one of Daigle-Williamson’s most important dialogue partners—Ransom is a Beatrician character for Jane. The reader can parallel Jane’s encounter with Ransom in the study with Dante’s encounter with Beatrice in the garden—and consequently see that encounter with Beatrice emerge again and again in Lewis’ fiction. In a dramatic reversal worthy of more critical work, Jane emerges as the Beatrice for Mark, both theologically and as the figural centre of his conversion.

Thus, looking not just for quotes and ideas of Dante in Lewis but looking also for that relational element, someone like Beatrice and Virgil works very well.

Indeed, I wish that Daigle-Williamson went further along this path. My “Mixed Metaphors” chapter argues that Lewis doesn’t just bring references in from other texts, but entire worlds. Unfortunately, few critics are even considering that world-shaping and imaginative construct as something to consider in intertextuality. Echoes are not always verbal, but might be imagistic, spatial, rhythmic, structural, or doctrinal. So I would have liked to see more focus on the spatial geography and speculative cosmography of each text. Fortunately, Daigle-Williamson does take time to consider more than just the verbal and literary echoes, allusions, and quotations that are the focus of her work.

This article is really about using a great study in a good book and seeing how thinking about “intertextuality” in more complex ways can open up the reading for us, making the study of stories inside other stories more dynamic and rewarding.

A Critique of Reflecting the Eternal

A Critique of Reflecting the Eternal

Because Reflecting the Eternal: Dante’s Divine Comedy in the Novels of C.S. Lewis was such a rich resource, excellently conceived and carefully researched, I have offered a substantial critique in some related ways. I won’t repeat some of my quibbles about interpretation or gaps in Reflecting the Eternal; you can read about these in the full review here (and stronger Dante scholars will bring the question alive far better than I can).

I will note, in terms of approach, an interesting problem to “data-driven” studies like this one. After highlighting key points in the central journey section of each chapter, Daigle-Williamson then lays out the pertinent Dantean parallels line-by-line through the text. This is precisely how I would have written the book. While I would dearly love to see the spreadsheet behind the volume, there is a weakness to the approach that made me rewrite the entire book I have been working on. As the intertextual data isn’t weighted, exceptionally strong links are set next to weaker ones with little differentiation in the paragraph. Part of Daigle-Williamson’s thesis is that Lewis is intentionally and carefully shaping his intertextual use of Dante. A vast amount of data—and there really is a large number of links—will not demonstrate this thesis more than the correct data, and I found myself as a reader putting √ and X marks on the page next to stronger and weaker examples.

A more nuanced approach—and one that would increase readability—would be to admit the thinner links but use the weight of the stronger links to carry the argument. When I talked to Marsha about this at a conference, she seemed to enjoy rethinking about writing in that way. Certainly, when she has presented material in talks, she has chosen the stronger links. She also reminded me that, fresh as I found he material, the book was an older project rewritten for readers increasingly interested in medieval studies about C.S. Lewis.

Rethinking Eternal Reflections

Rethinking Eternal Reflections

In contemporary literary criticism, there is perhaps an over-reliance upon literary theory and approaches that can sometimes be faddish or cause the text at issue to disappear. However, when we use literary tools, we are always doing something–whether we are intentional about that or not. If we consider the roots of language, the relationship of the text to the author or reader, the kinds of political questions before and in and after the text, or the way “us” and “them” work in the story–the kinds of questions we are always asking of great stories and poems–we are doing theory. I have argued that in Lewis studies there is not always sufficient attention to theory, which is partly a reaction against a lot of scholarly nonsense that we encounter every day as critics. In the case of Reflecting the Eternal, inattention to theory means a loss of the potential impact of a great book.

In particular, how do books use other books? “Intertextual Theory” is simply a way of answering that question.

Marsha Daigle-Williamson’s dialogue with secondary sources is superb. Missing from her bibliography, however, is a grounding in intertextual theory. The resources for studying intertextuality are rich, from Gérard Genette, Roland Barthes, and Julia Kristeva of the 1960s, to later critics such as Harold Bloom, Umberto Eco, and John Hollander. While complete expertise in the field is unnecessary, knowledge of a survey like Graham Allen’s Intertextuality (2008) would show the potential that some grounding in theory could give.

Marsha Daigle-Williamson’s dialogue with secondary sources is superb. Missing from her bibliography, however, is a grounding in intertextual theory. The resources for studying intertextuality are rich, from Gérard Genette, Roland Barthes, and Julia Kristeva of the 1960s, to later critics such as Harold Bloom, Umberto Eco, and John Hollander. While complete expertise in the field is unnecessary, knowledge of a survey like Graham Allen’s Intertextuality (2008) would show the potential that some grounding in theory could give.

For example, Daigle-Williamson is great at recognizing that Dante’s links in Lewis are multilayered, appearing in many forms beyond allusion and quotation. In the way she presents her findings, however, she has an unnecessarily linear appreciation of the texts behind Lewis’s text. Though careful readers know it is more complex, Daigle-Williamson’s approach ends up looking like so many others who talk about intertextuality in very linear ways:

However, there are many possible text relationships. We can imagine, as Marsha Daigle-Williamson has done, Dante taken up by Lewis when he is writing his 20th-century fantasy and science fiction. However, isn’t it the case that Lewis is working as a professional critic and historian, so he uses Dante, talks about him, teaches him, chats with friends about him, and so on. Lewis has infused Dante into his life in myriad ways. While that’s a complex set of interrelations, here is how we might visualize a simplified view of Dante taken up by Lewis as a critic and then used in fiction:

And indeed, does Lewis use Dante differently as a critic than as an imaginative writer? It is worth thinking about what that might look like–not just visually, but in the way that we read as readers.

But even as we create these overly simple cartoons of Lewis’ reading to capture a more complex reality, we must remember that Lewis’ conversation partners are broader than his own generation. As Lewis was a historian of Medieval and Renaissance literature, and deeply influenced by Modern writers like Dr. Johnson, George MacDonald, William Morris, and Charles Williams, we have to recognize that Lewis receives Dante through various kinds of writers and thinkers:

Thus, it matters to think not just about Dante in Lewis, but Shakespeare’s Dante in Lewis, or Milton struggling with and against Dante in Lewis, or Williams doing whatever it is Williams does with Dante in Descent into Hell in Lewis. Do you see the imaginative possibilities?

And just as the readers of Dante since Dante are part of a complex of conversation partners that make up Lewis’ idea of Dante, that must include Dante scholarship (up to Lewis’ time), and other resources, like mythologies, biblical materials, and the like:

There could be a lot of in-flow tabs there. Still, even if we use our visual imaginations, we are being too linear, for Dante himself is part of that cluster of mythological, classical, medieval, and biblical ideas and images that come to Lewis through Dante:

And if we can think of “Dante” as that complex of realities and Lewis receiving that in many ways, I wonder how often Lewis was working with Dante with his Bible open or talking through a theological concept over a pint or while preparing a radio script. Indeed, how often might Lewis have been struggling with a theological or literary question and turns to Dante as a conversation partner:

And so on. These are not all the possible intertextual links and they are reduced to their simplest components. These idea maps, however, make clear that the project of using Dante—whether conscious or not—is far more nuanced and complex than we might at first think. There is a richness to that multilayered reality that I think could enhance Daigle-Williamson’s impact because she anticipates that complexity. And I think that this is a concept that needs more attention in Intertextual Theory.

Lewis and Intertextual Theory

Intriguingly, as we are thinking about Intertextual Theory, challenging it and reshaping, it is worth noting that C.S. Lewis himself is one of the important thinkers about intertextuality. This is an argument that I made in the Inklings and King Arthur volume edited by Sørina Higgins, in editing stages at about the time that Reflecting the Eternal was coming to print. Marsha Daigle-Williamson could not have predicted my argument, though it is frustrating that scholars of Intertextual Theory have not understood the ways that Lewis can help us think about intertextuality, and I would like Lewis scholars to be more attuned to what Lewis thinks is happening as texts move and live and have their being. I believe that, my work aside, Daigle-Williamson could have used Lewis as a critic to his own material more critically–though she does refer to Lewis’ work on Dante at various points.

Intriguingly, as we are thinking about Intertextual Theory, challenging it and reshaping, it is worth noting that C.S. Lewis himself is one of the important thinkers about intertextuality. This is an argument that I made in the Inklings and King Arthur volume edited by Sørina Higgins, in editing stages at about the time that Reflecting the Eternal was coming to print. Marsha Daigle-Williamson could not have predicted my argument, though it is frustrating that scholars of Intertextual Theory have not understood the ways that Lewis can help us think about intertextuality, and I would like Lewis scholars to be more attuned to what Lewis thinks is happening as texts move and live and have their being. I believe that, my work aside, Daigle-Williamson could have used Lewis as a critic to his own material more critically–though she does refer to Lewis’ work on Dante at various points.

Going beyond this one book to theories of intertextuality, I have argued in “Mixed Metaphors and Hyperlinked Worlds: A Study of Intertextuality in C.S. Lewis’s Ransom Cycle” that when Lewis gives an intertextual nod, he is doing something quite dynamic. For example, he makes quite subtle links to three other Inklings in That Hideous Strength. In noting Barfield’s “ancient unities” or Tolkien’s Númenor or Williams’ Logres, Lewis is creating something like a “hyperlink”–so that when we mentally “click” on the link, we find ourselves jumping out of the text back into some other place, just like clicking a hyperlink on this website will bring you to another article. In hyperlinking the idea, however, I argue that Lewis is not just going back to a quotation or even a single idea, but is bringing the entire world of thought or speculative universe into his story. It isn’t just that Tolkien’s Númenor sits in a book on the fictional shelves of the Manor at St. Anne’s library, but that, somehow, the world of That Hideous Strength is bound up with the Númenorean history, its culture and values and story. Barfield’s philosophy does not merely shape the ideas of Lewis’ dystopia, but infiltrates it–as does Williams’ concept of “Logres,” deeper than a single image or idea. All of these worlds of thought and story are drawn into Lewis’ own story, providing layers of meaning and experience to the characters and the readers.

In her introduction, Daigle-Williamson lays out critical foundational approaches to the book, arguing that Lewis takes his lead from medieval authors both structurally and theologically. I think she is precisely correct in this. Dante is chief among the authors that Lewis follows, and in delineating six kinds of intertextuality, she seems to want to include the echo of world-building that I am talking about here–the hyperlinking not just of quotations or allusions, but entire worlds. Rooting herself more deeply in Lewis’ own literary work and being clear about linear and dynamic relationships between texts could help her work be clearer. And there is one more way that I think that clarity could be both useful and interesting.

In her introduction, Daigle-Williamson lays out critical foundational approaches to the book, arguing that Lewis takes his lead from medieval authors both structurally and theologically. I think she is precisely correct in this. Dante is chief among the authors that Lewis follows, and in delineating six kinds of intertextuality, she seems to want to include the echo of world-building that I am talking about here–the hyperlinking not just of quotations or allusions, but entire worlds. Rooting herself more deeply in Lewis’ own literary work and being clear about linear and dynamic relationships between texts could help her work be clearer. And there is one more way that I think that clarity could be both useful and interesting.

If I am correct about the dynamic ways that Lewis is working intertextually-informed as they are by his own thinking about reading–we might want to ask this question: To what degree was this intertextual layering intentional on Lewis’ part?

My larger review essay of Reflecting the Eternal goes into a detailed critique of this question. Marsha Daigle-Williamson writes as if Lewis intended each link he makes, that he designed his approaches, selected all of his allusions and quotations and mental links to other worlds, understanding what those links would do for the reader in his own fiction writing. And yet, she knows that Lewis is likely a more instinctive and instinctual writer, and deals with that question in her introduction:

How conscious and deliberate are these parallels to Dante on Lewis’s part? On several occasions in response to specific queries from readers, Lewis confirms that particular parallels with Dante in his novels are intentional. Otherwise, Lewis is silent. We can only wish that readers had asked him more questions. However, the sheer number of specific allusions and parallels are evidence, at the very least, that Dante’s poem was an integral part of Lewis’s thinking (6).

The paragraph concludes correctly, but must we narrow “thinking” to the conscious activity of making links between two authors and their respective text-worlds? Daigle-Williamson clearly views the process as an active, conscious one on Lewis’ part, concluding that,

The paragraph concludes correctly, but must we narrow “thinking” to the conscious activity of making links between two authors and their respective text-worlds? Daigle-Williamson clearly views the process as an active, conscious one on Lewis’ part, concluding that,

“Once a specific genre was chosen [for his next piece of fiction], Lewis’s use of Dante was necessarily tailored to that genre” (205).

I would push back on this point for various reasons. Primarily, we don’t know all parts of Lewis’ writing process, but only the final product supplemented by a few letters and an occasional draft scrap in archives. In her footnote to the section I quoted, Daigle-Williamson refers to a caution that Michael Ward gives about the hidden nature of an author’s work, but reveals her hope that as time goes on, “more and more of Lewis’s literary strategies will be uncovered” (211). As a critic and writer and historian, I hope the same. But this fascination with scrying an obscured strategy can draw the reader away from the extraordinarily helpful analysis to the question of the credibility of the writing strategy thesis. In this case, there is simply not enough evidence to go far with Daigle-Williamson on the intentionality thesis.

Moreover, as we think of ourselves and our relationship with books, is not the process of intertextuality more dynamic than linear? True, we intentionally quote or echo an author at the dinner table, on social media, or in our writing. But have you not gone back to work that you have some distance from and discovered links that you never imagined? When we fully immerse ourselves in a text and an author as Lewis did of Dante and the period, we find literary accents slip into our speech and narrative perspectives begin to shift as the way we make connections or view the world takes on new forms. This intertextual relationship is subtle and sublime: the question of strategy and authorial intention, beyond its unavailability to us, is a different kind of question.

As biographers of Lewis, we want to keep asking the question, “What did Lewis know he was doing here?” As readers of his fiction, though, I don’t think we have to be limited in this way. There is so much richness that springs out of Lewis’ deeply referential stories. As they work on us emotionally, subconsciously, and in unseen ways, I think we need to give room for the instinctive element in Lewis as well.

As biographers of Lewis, we want to keep asking the question, “What did Lewis know he was doing here?” As readers of his fiction, though, I don’t think we have to be limited in this way. There is so much richness that springs out of Lewis’ deeply referential stories. As they work on us emotionally, subconsciously, and in unseen ways, I think we need to give room for the instinctive element in Lewis as well.

If we flip the question from “Lewis’s use of Dante” (see p. 201) to “where Dante is in and behind Lewis’ fiction,” we avoid some of the limitations that a question of specific intention would require. In that latter question, Daigle-Williamson is a master, and we can agree with her that Dante is Lewis’ guide in the way that Virgil was Dante’s guide. This is an elegant argument. Distinguishing these things will highlight her very fine conclusion:

A reader can find many quotes from Dante in all of Lewis’s nonfiction, including his letters, but after his first novel, Lewis never again quotes Dante’s poem directly in his longer fiction. The Divine Comedy recedes from a kind of facile visibility to be woven into the fabric of Lewis’s stories in subtle, powerful ways (201-2).

Concluding Thoughts

Loving what I have received from Reflecting the Eternal, I hope that certain things will follow from Marsha Daigle-Williamson’s work (and my own provocations) here.

First, as C.S. Lewis’ poetry can enlighten his fiction and has value on its own, I hope that someone will do for Dante and Lewis’ prose what Daigle-Williamson did for his fiction. For example, in the second of Lewis’ “Five Sonnets,” we read:

but first

Down to the frozen centre, up the vast

Mountain of pain, from world to world, he passed.

Here we see a Dantean allusion where Dante’s spatial geography is echoed in the human experience of pain. What would a spatial reading of Lewis’ poetry look like? How does Lewis bring not just Dante’s words and images but his entire world into his poetry? I hope for a second volume subtitled Dante’s Divine Comedy in the Criticism and Poetry of C.S. Lewis is in the works–though, sadly, it will need to come from the hand of another scholar.

Second, C.S. Lewis read so much and so broadly that it would be impossible to trace his entire book journey. However, I hope that, out of the community of scholarship, this book might provoke other similar explorations of the various threads of Lewis’ ingrained intertextuality. What about Lewis’ other canonical friends, like Homer, Augustine, Boethius, Edmund Spenser, John Milton, Jane Austen, the Inklings, or the Arthuriad?

Second, C.S. Lewis read so much and so broadly that it would be impossible to trace his entire book journey. However, I hope that, out of the community of scholarship, this book might provoke other similar explorations of the various threads of Lewis’ ingrained intertextuality. What about Lewis’ other canonical friends, like Homer, Augustine, Boethius, Edmund Spenser, John Milton, Jane Austen, the Inklings, or the Arthuriad?

Finally, my interest in intertextuality is not anatomical–the links between texts–but how authors build their speculative universes and create meaning, how they invite other fictional worlds into their own, and how our reading experience is richer as a result. Still, I hope that we can be clearer in our methods as critics. Doing so, and seeing Lewis as a theoretician as well as critic and historian, will show Lewis’ value for helping us thinking about writing and reading (i.e., literary theory) in more effective and inviting ways.

Some Blog Posts on Intertextuality

- Bandersnatch and Creative Collaboration by Diana Pavlac Glyer (see also a note here)

- The Stories before the Hobbit: Tolkien Intertextuality, or the Sources behind his Diamond Waistcoat

- The Hobbit as a Living Text: The Battle of 5 Blogs

- When You Reach Me: A New Kind of Intertextuality?

- Charles Williams’ Arthurian Apocalypse: Thoughts on “The Son of Lancelot”

- Star Wars and The Sword in the Stone

- The Stories behind Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice

- Lewis, Wagner, and Frankenstein: Literary Accident or Reader’s Providence?

- The Thing about Riding Centaurs: A Note on Narnia, Harry Potter, Madeline Miller’s Song of Achilles, and the Black Stallion

- Three Myths Retold: Madeline Miller’s Song of Achilles, Margaret Atwood’s Penelopiad, and C.S. Lewis’ Till We Have Faces

- Age of Ultron: Mythic Mess or the Absurd Man?

- Why Do They Quote Shakespeare on Mercury?

- An Essential Reading List from C.S. Lewis: An Experiment on An Experiment in Criticism (see also Harold Bloom here and here)

- Michael Ward’s Planet Narnia Thesis (see resource page here and review essay here)

- Why is Merlin in That Hideous Strength?

- Jill Pole’s Road to Emmaus

- The Fictional Universe of Narnia

- (and, sort of here) On a Picture by Chirico: A Proposal about the Creation of Narnia