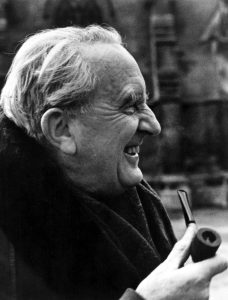

As J.R.R. Tolkien was born 69,425,820 minutes ago, give or take. The Tolkien Society is again raising a toast to the Professor on his birthday, 3 January 2023 (see here). After Bilbo left the Shire on his eleventy-first birthday in The Lord of the Rings, Frodo toasted his uncle on their shared birthday each year. Tolkien friends, fans, and fellows continue the tradition, toasting the maker of Middle-earth on this day. J.R.R. Tolkien was born in South Africa on 3 January 1892, making this (if he had had Hobbitish longevity) his 132nd. The Tolkien Society invites us to celebrate the birthday by raising a glass of comfort or joy at 9pm your local time, simply toasting “The Professor!”

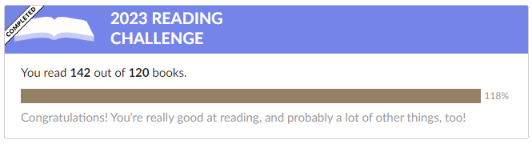

In honour of Tolkien’s birthday, I like to update the catalogue of Tolkien posts featured here on A Pilgrim in Narnia. I am in the midst of a monograph going to my editor very soon, and so 2022-23 has been a bit thin on new or substantially rewritten content. Still, I wrote or rewrote 8 Tolkien-related articles, reflections, reviews, or blog posts, and I reblogged two new essays that I thought were pretty great.

Tolkien posts continue to be popular among readers of A Pilgrim in Narnia. 4 of the top 15 most-read pieces are about Tolkien. The text that continues to top that Tolkien tally is my “Approaching The Silmarillion for the First Time,” the 2nd most-read post of 2023. Reflections inspired by Tolkien’s correspondence continue to spin, like “The Tolkien Letters that Changed C.S. Lewis’ Life” and “The Tolkien Letter that Every Lover of Middle-earth Must Read.” Another one of these letter-posts is “The Shocking Reason Tolkien Finished The Lord of the Rings,” which cracked the top 15 among 2023 readers. When I wrote this sassily titled piece, I was on the eve of one of the most challenging times in my life. Now, as I struggle to finish a writing project in another deeply difficult time, I have come to find comfort in it. I’m glad people are reading it.

While it peaked in 2022, my tribute to Christopher Tolkien was also popular this past year.

That said, it has been a hard couple of years for me, Tolkienistically speaking. In 2022, I was supervising Tolkien projects and spoke at Tolkienmoot in the summer (really, I just joined in the fun). I read and (positively) reviewed Carl Hostetter’s editorial gift to scholars and fans, The Nature of Middle-earth. It should appear in Sehnsucht: The C.S. Lewis Journal in the coming months. It has been a great couple of years reading what I catch myself thinking of as the “nonfiction” of the legendarium–The Nature of Middle-earth fits the bill, but I’m also thinking of The Silmarillion, Sauron Defeated, and Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth, as well as a few other points in History of Middle-earth (e.g., see here).

And despite my deep desire to do so, I wasn’t able to make space this year to write about my thoughts or to read either The Lord of the Rings or The Hobbit. These stories genuinely refresh my spirit and invite joy, so I miss them when they are not part of my year. And while I began 2022 with the hopeful news of a new Tolkien adaptation, the digital debate was so often infused with invective designed to strike at the most intimate parts of our human being and living. I became ashamed of my literary, religious, and activist communities as everything turned sour. I lost heart. Despite a dozen attempts to rewrite my “Approaching The Silmarillion for the First Time” article and provide an update to my “J.R.R. Tolkien’s Texts on The (Down)Fall of Númenor” piece (following great reader notes and the release of the Brian Sibley edited, The Fall of Númenor), I simply could not complete anything.

Wisely, perhaps, I stepped out of the conversation and stopped watching the Rings of Power Amazon Prime serial. While I have been called immoral and disloyal, I have found that adaptations on the stage, in film or on television, and by audiobook can enrich my experience of reading the texts that are most meaningful for me. Although I am in the same place a year later, I look forward to a season ahead when I can return to the simple pleasures of reading and watching beyond the courts of rage.

Here at A Pilgrim in Narnia, I desire to curate a space for people who love the simple pleasures of a well-told story and a well-built world. Thus, this “brace” of Tolkien posts. Over 110 article links are now listed here–far more than a brace, methinks. So, I hope this great feast of guest bloggers, hot links, and feature posts will complement your Tolkien reading and inspire you to widen and deepen your Tolkienaphilia. And, of course, a glass raised to the Professor for all of the 6887 weeks since his birth, and, I hope, 6887 weeks of great reading to come.

Tolkien’s Ideas at Work in Word

Tolkien’s work is rich with reflections on the world around us. In posts like “Let Folly Be Our Cloak: Power in the Lord of the Rings” and “Affirming Creation in LOTR” (updated in 2021), I explore themes related to ideas that are central to Tolkien’s beliefs. The latter idea, creation and good things green, is also covered with Samwise Gamgee here and with Radagast the Brown here. One that resonates long after the first reading is the theme of Providence, which I explore in “Accidental Riddles in the Invisible Dark” (updated for Hobbit Day 2021 here). I reblogged Stephen Winter’s “”Your Fingers Would Remember Their Old Strength Better, if They Grasped a Sword-hilt’: Gandalf and The Healing of Théoden” to capture a similar inspiration from the text.

I would also encourage readers to check out the annual J.R.R. Tolkien Lecture on Fantasy Literature at Pembroke College, Oxford. Tolkien editor and historical fantasist Guy Gavriel Kay was the 2021 lecturer, which I discuss here: “Just Enough Light: Some Thoughts on Fantasy and Literature.”

One surprising connection was “Simone de Beauvoir and the Keyspring of the Lord of the Rings“–a pairing that many would find unusual and includes some great old footage. Guest blogger Trish Lambert concluded the discussion with “Friendship Over Family in Lord of the the Rings.” Author Tim Willard talks about “Eucatastrophe: J.R.R Tolkien & C.S. Lewis’s Magic Formula for Hope.” And you can follow Stephen Winter’s LOTR thought project here and Luke Shelton’s Tolkien Experience Project here.

Perhaps Tolkien’s most central contribution beyond the storied world is his idea of subcreation in the poem, “Mythopoeia” and in other works like the essay, “On Fairy-stories” and the allegorical short story, “Leaf by Niggle.” I have been reading a lot about this concept–partly because of students working on the idea–and appreciated poet-philosopher Malcolm Guite’s take on it here.

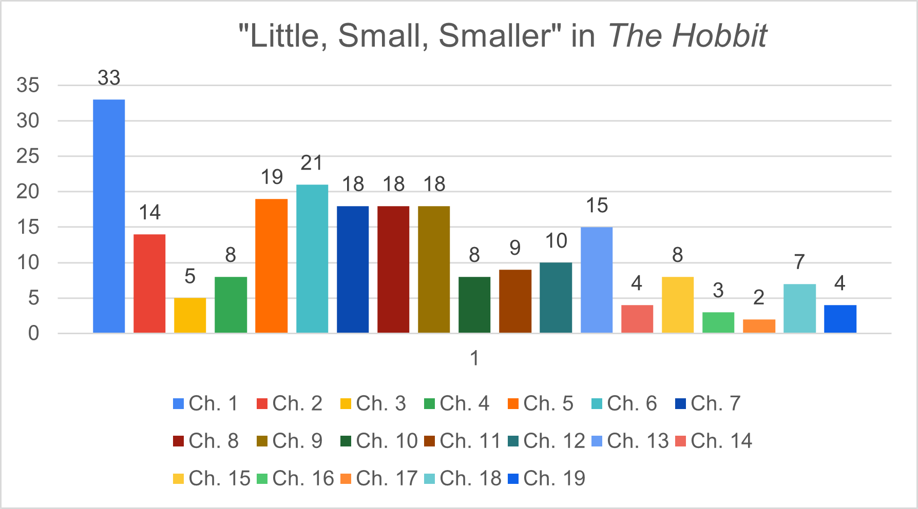

I have admitted before that my Tolkien reading and writing is just pure enjoyment. I don’t pretend to have much original to say on the scholarly level. My most important contribution, I think, is my Theology on Tap talk, called “A Hobbit’s Theology,” which I rewrote in 2021 for Northwind Theological Seminary’s doctoral degree in Romantic Theology (which has a Tolkien studies track). It is one of the ideas I am struggling with, most specifically in my academic work, and I hope to do some future writing on the topic. Out of that same lecture series came this piece, “‘Small’ and ‘Little’, a Literary Experiment on J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit,” where I used some word-date analysis by Sparrow Alden and her “Words That You Were Saying” Tolkien word-study blog.

Sparrow’s research, I should note, is part of a strong community of Tolkien digital humanities research (e.g., Emil Johansson’s LOTRProject, or Chiara Palladino and James Tauber’s Digital Tolkien Project, or Joe Hoffman’s blog, or this resource list here), and is definitely worth checking out.

In a similar mode–thinking of Tolkien’s work through a theological lens–is Mickey Corso’s excellent work on Tolkien and Catholicism. The video conversation of “The Lady and Our Lady: Galadriel as a ‘Reflexion’ of Mary,” A Signum Thesis Theatre on Tolkien and Catholicism by Mickey Corso, is now online. In this mode, I blogged “’Joy Beyond the Walls of the World, Poignant as Grief,’” a conversation between J.R.R. Tolkien and Frederick Buechner. As a Tolkien Easter reflection, I reblogged Wade archivist Laura Schmidt’s piece, “Wounds that Never Fully Heal.” Also, check out a couple of video conversations: “Inklings of Imagination” with myself, Malcolm Guite, and Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson on the theological imagination, and “Imaginative Hospitality” from a theological angle with Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson, Diana Glyer, Michael Ward, and Fr. Andrew Cuneo.

Tolkien as a Writer

I remain fascinated by Tolkien’s development as an author. The most popular of the pieces I wrote was the coyly titled, “The Shocking Reason Tolkien Finished The Lord of the Rings.” The reason is, of course, not all that shocking, but could be helpful for the subcreators amongst us. Two more substantial posts on the topic are “12 Reasons not to Write Lord of the Rings, or an Ode Against the Muses” and “The Stories before the Hobbit: Tolkien Intertextuality, or the Sources behind his Diamond Waistcoat.”

C.S. Lewis also took an interest in Tolkien’s formation (see “Book Reviews” below). You can read more about it in Diana Pavlac Glyer’s Bandersnatch, and in this blog post, “‘So Multifarious and So True’: The C.S. Lewis Blurb for the Fellowship of the Ring.” Lewis’ support for Tolkien did not go unrewarded. Besides the great joy of Tolkien’s work, there was a time when Tolkien interceded a time or two on Lewis’ behalf. Friendship goes both ways. Tolkien historian John Garth takes some time to explore this literary friendship further in his detailed explanation of “When Tolkien reinvented Atlantis and Lewis went to Mars.”

One post from 2018 created a lot of (pretty positive) controversy. In “Lewis, Tolkien and Different Views of Fan Fiction” I invited thought about two trends: Tolkien readers’ resistance to fan fiction (in concert with Tolkien himself), and a strong trend of good fanfiction from Tolkien lovers. The post is worth reading, but so are the 100+ comments. But my most substantial and original written piece on Tolkien’s writing, I think, is the 2020 article, “Trees, Leaves, Vines, Circles: The Layered Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Fiction, A Note on ‘Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth,’” which includes art by Emily Austin.

And one of the more popular posts of 2016 was a very personal one about me as a writer and researcher, “Battling a Mountain of Neglect with J.R.R. Tolkien.” Though I am still not sure if I should have written that post, it has connected with readers. In retrospect, 2016 was a very difficult year in many ways.

In a more jocular frame of mind, in 2023 I included The Hobbit and LOTR in “Sharp Novel Minds and Pithy First Lines, with Jane Austen, C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, Dorothy Sayers, Geo. MacDonald, G.K. Chesterton, Ray Bradbury, N.K. Jemisin, Nalo Hopkinson, Margaret Atwood and more!“

The Tolkien Letter Series

Tolkien’s letters remain a rich resource for researchers that is available to everyday readers–and usually available used for a pretty low price. In these letters, I discovered the tidbits on writing above, as well as notes like “The Tolkien Letters that Changed C.S. Lewis’ Life” (which remains a top 10 post). But it goes much deeper. In “The Tolkien Letter that Every Lover of Middle-Earth Must Read“–also a top 10 post–I include much of a draft that Tolkien wrote to a Mrs. Mitchison that fills in much of the background to Middle-earth. I also took the time to put Tolkien’s great “I am in fact a Hobbit (in all but size)” quotation in context, which I updated in 2020 with a note on books and their authors.

A more sober but quite moving letter is the one that I featured in this popular post from fall 2018: “The Last Letter of J.R.R. Tolkien, on the 45th Anniversary of His Death.” It is a post to read when raising a toast. And now, with the passing of Christopher Tolkien, son of the genius, I have added a second toasting post. In my 2020 tribute piece, Christopher Tolkien, Curator of Middle-earth, Has Died, there is also a pretty poignant letter from his father. I hope you enjoy it.

The letters afforded me some time to think about some other ideas. In a longer popular post that any conlanger will know is poorly named–“Why Tolkien Thought Fake Languages Fail,”–I discussed Tolkien’s own constructed language program and surmised with the Professor that conlangs fail when they lack a mythic element. I think I am mostly correct. And the essay is quite fun, even if I am missing some key elements. I was able to push further when I did a personal response to new Tolkien language research in this post: “J.R.R. Tolkien’s “Secret Vice” and My Secret Love: Thoughts on Dimitra Fimi and Andrew Higgins’ Critical Edition of A Secret Vice: Tolkien on Invented Language.”

Recently, I was thinking through the relationship between C.S. Lewis and T.S. Eliot. In the midst of that search, I found Tolkien’s 30 August 1964 letter to Anne Barrett of the publisher, Houghton Mifflin. On the anniversary of that letter, I shared this piece: “Great and Little Men: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Letter about C.S. Lewis and T.S. Eliot.” As with much of Tolkien’s praise of Lewis, there is a slighting comment or two. And yet, it is a powerful bit of testimony to the content of C.S. Lewis’ character, in his friend’s estimation. In this vein, check out “C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien: Friendship, True Myth, And Platonism,” an academic paper by Justin Keena published here on A Pilgrim in Narnia.

Finally, a little fun with the post, “When Sam Gamgee Wrote to J.R.R. Tolkien.” As you might guess, it is about a real-life Sam Gamgee who sends a note to the maker of Middle-earth. And, of course, when the season of advent returns, check out the Father Christmas Letters. While there are others with better Father Christmas Letters posts and articles, my piece got picked up on Reddit in 2021, so I touched it up again for that Christmas Day reading.

The Silmarillion Project

This is a newish feature for me, partly because 2017 was the year I completed The Silmarillion in its entirety in a single reading (rather than the higgledy-piggledy approach of cherry-picking stories and languishing in the mythic portions, as I am wont to do). I reread it in early 2020 and mid-2022, this time by audiobook, and enjoyed it deeply. Still, I find it a challenge. I thought I would take advantage of my status as a Silm-struggler to offer suggestions and resources to people looking to extend their reading of the Legendarium.

In “Approaching “The Silmarillion” for the First Time,” I made a few suggestions for readers intending to read this peculiar book for the first time. If you are a fellow Silm-struggler, I hope this helps you get a fuller experience of a beautiful collection of texts. That experience inspired me to write “A Call for a Silmarillion Talmud,” an unusual post for Tolkienists with more creative and technological skills to consider.

Finally, I had to write as a fan and scholar together in considering the cycle of Lúthien and Beren. In “Of Beren and Lúthien, Of Myth and the Worlds We Love,” I talk about my love of the story and its links to the Legendarium while noting my hope for the 2017 release of the Beren and Lúthien materials and sharing some Silmarillion-inspired artwork. In my tribute to Star Wars, I speculate that to the degree that Star Wars succeeds, at least for me, it is mythopoeic–a myth-making project, a myth itself, or something like it.

Thinking about Tolkien Studies

Over the last few years, I have slowly been gathering an understanding of Tolkien studies as a discipline. I am far from an expert, but I have been struck by the most robust Tolkien books and essays I have encountered. Verlyn Flieger‘s Splintered Light is a lyrically beautiful critical study: it is tight and thematically vibrant, invested in the entire corpus, and yet wholly accessible as a single study of light and darkness. John Garth‘s Tolkien and the Great War is not simply one of the best Tolkien historical works I have read, and is by far my favourite study on WWI. There are numerous vital medievalist approaches to and with Tolkien, and Tom Shippey is a Tolkien scholar of great clarity and energy. Among younger scholars, I greatly admire Dimitra Fimi’s Mythopoeic Award-winning Tolkien, Race, and Cultural History: From Fairies to Hobbits. I carefully watch what her students and colleagues are doing.

Inspired by this work–and a sense of frustration in Lewis studies–I began reflecting on Tolkien Studies in 2021. The result was a somewhat saucy but generally thoughtful series on “Why is Tolkien Scholarship Stronger than Lewis Scholarship?” in three parts:

- Part 1: Creative Breaks that Inspired Tolkien Readers (where I describe four break-out moments or waves in Tolkien readership)

- Part 2: Literary Breadth and Depth

- Part 3: Other Factors (including comfort with literary theory, the work of literary societies to engender scholarship, and some cultural aspects of Lewis studies)

You can read a somewhat tongue-in-cheek response by Joe Hoffman that I quite like through “The Idiosopher’s Razor: The Missing Element in Metacritical Analysis of Tolkien and Lewis Scholarship.”

Though I’m still catching up in 2023, my work turned out to be once again relevant as “Tolkien Studies Projects Swept the Mythopoeic Scholarship Award Shortlist in Inklings Studies.” While my vote was for Garth’s The Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien (see my blog post on the results here), the 2021 winner was John M. Bowers for Tolkien’s Lost Chaucer. A smart and helpful book from a Chaucer specialist who came to love Tolkien’s work later in life, I wrote a substantial review and response, “The Doom and Destiny of Tolkien’s Chaucer Research: A Note on John M. Bowers, Tolkien’s Lost Chaucer,” after working through the text while teaching Chaucer locally.

Interested in continuing to resource Inklings readers, I published “5 Ways to Find Open Source Academic Research on C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and the Inklings“–a living post aI have updated as scholars and librarians have written in. And I have edited and published a guest essay by G. Connor Salter, “Lewis and Tolkien among American Evangelicals“–an important contribution to reception studies.

Reading Tolkien in Community

One of my first digital exchanges was participating in The Hobbit Read Along–you can still see the great collection of posts online. While doing this shared project, I was reading The Hobbit to my 8-year-old son. It was a great experience, but I made the mistake of voicing accents to distinguish characters early on in the book. That’s fine when you’ve got oafish trolls or prim little hobbits. But a baker’s dozen of dwarfs stretched my abilities! You can read about my reading-aloud adventures here.

In reading aloud, I was really struck by the theme of providence in The Hobbit. I’m sure others have talked about it, but “Accidental Riddles in the Invisible Dark (Chapter 5)” is an excellent example of that hand of guidance behind the scenes (touched up for Hobbit Day in 2021).

In 2021, I used Tolkien Reading Day (March 25th) to share some of my fun Tolkien bookstore discoveries and to think about Tolkien’s audiobooks as “adaptations” or interpretations: “Reading J.R.R. Tolkien by Audiobook and Adaptation: Thoughts on a Portland Discovery.” In this piece, I talk about The Green Hand in Portland, ME (I visited again in the summer of 2023, but did not have any Tolkien epiphanies), and how at Enterprise Records, I found a beautiful library withdrawal vinyl collection of the Nicol Williamson’s abridged reading of The Hobbit. Spinning this record, and thinking about Andy Serkis’ version of The Hobbit, I discuss what audiobook readings do for me on an imaginative level. I also talk about some of my Tolkien collectible books I’ve discovered hither and yon. None of these are super valuable: a US 1st edition of The Silmarillion that I got for $10 at a used bookstore (and I added a UK 1st edition this year for $20), a nice boxed illustrated anniversary edition of The Hobbit, the original wide-sized printing of the Tolkien-illustrated Mr. Bliss, and my UK 2nd edition Lord of the Rings, which looks nice on the shelf. Truth be told, I also love the design of the Middle-earth volumes from the last decade or so, and my wife and I were pleased to give our son hardcover editions of Beren and Lúthien and The Fall of Gondolin for Christmas.

Film Reviews

When the teaser trailer of the third film, The Battle of Five Armies, was released, I wrote “Faint Hope for The Hobbit.” Although it is clear in the trailers that this is a war and intrigue film, I still had some hope I would enjoy it. The huge comment section shows in that post shows that not everyone agreed it was possible!

My review of An Unexpected Journey captures the tug back and forth I feel about the films. I called it “Not All Adventures Begin Well,” and it is a much more positive review than many of the hardcore Tolkien fans or academics. And it gives this cool dwarf picture:

“What Have We Done?” These words are breathed in the dying moments of the second installation of The Hobbit adaptation, The Desolation of Smaug. In this review, I think about what it means to do film adaptations. While I do not hate this Hobbit trilogy, I think Peter Jackson got lost.

When I finally got to The Battle of 5 Armies, I decided doing a Battle of 5 Blogs would be fun. 5 other bloggers joined it, making it a Battle of 6 Blogs! But the armies are pretty tough to count, anyhow. I titled my blog “The Hobbit as Living Text.” It was a controversial approach to the film, I know. Make sure you check out the other reviewer’s link here. Some of us chatted about the films in an All About Jack Podcast, which you can hear here and here.

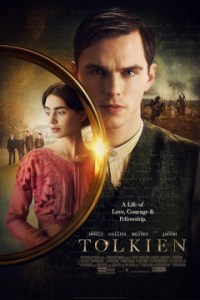

While these aren’t substantial reviews, I featured two indie films: a documentary on Tolkien’s Great War, and a fictional biopic recreating Tolkien’s invention of Middle Earth called Tolkien’s Road—both inspired, perhaps, by John Garth’s work.

Though the Hobbit films were unsatisfying, I still miss having a Tolkien-Peter Jackson epic to watch in theatre at Christmastime. 2019 supplied us, though, with the Tolkien biopic. Besides posting the trailers, I did lead-up posts like “Getting Ready for TOLKIEN: John Garth and Other Resources.” I still encourage people to read John Garth’s Tolkien and the Great War before watching the film, but I am not like many Tolkien fans who simply could not connect with the film. I reviewed it in three different ways, in three different places:

- I wrote a guest article for Forefront Festival called “The Tolkien Film and the Problem of Beauty“

- I had a discussion with Diana Glyer about the Tolkien Biopic on William O’Flaherty’s All About Jack Podcast

- My blog review was called “My Defiant Appreciation of the Biopic Tolkien,” and was shared by the Director as “my favourite to rule them all”–a neat high point in 2019

As I discussed above, I have decided to reserve judgment on the new Amazon Prime Rings of Power series–though I was excited enough to share the title announcement on the Blog nearly two years ago. Even with the announcement of the trailer, I could sense the tensions around the project and was trying to find a way through it. When I do write about the Rings of Power adaptation, I will likely be too late to be relevant! I am quite fine with that.

While I fled the Rings of Power arenas of debate, I spoke at Tolkienmoot in 2022 on the Second Age of Middle-earth, specifically the dissipation of Númenor. Thus my “J.R.R. Tolkien’s Texts on The (Down)Fall of Númenor” piece was anticipating both the Rings of Power series and the The Fall of Númenor, and Other Tales from the Second Age of Middle-earth edited by Brian Sibley, but was also the result of my thinking about that fine summer meeting.

Book Reviews

There was no more excellent friend of The Hobbit in the early days than C.S. Lewis. In “The Unpayable Debt of Writing Friends,” I talk about how, if it wasn’t for Lewis, Tolkien might never have finished The Hobbit, and the entire Lord of the Rings legendarium would be in an Oxford archive somewhere. Lewis not only encouraged the book to completion but also reviewed The Hobbit a few times. Here is his review in The Times Literary Supplement.

Lewis is not the only significant reviewer of The Hobbit. When he was 8, my son Nicolas published his review just as the first film was coming to the end of its run. When I was posting Nicolas’ review, I came across another young fellow–the son of Stanley Unwin, the first publisher to receive the remarkable manuscript of The Hobbit. Unsure how children would respond, he paid his son, Rayner, to write a response to the book. You can read about it here: “The Youngest Reviewers Get it Right, or The Hobbit in the Hands of Young Men.”

I have also done more book reviewing in the last couple of years on this blog. I note Fimi & Higgins’ “Secret Vice” above, as well as my review of Bower on Tolkien’s Lost Chaucer. I reviewed Verlyn Flieger’s edition of Tolkien’s The Story of Kullervo, which I quite loved. I also reblogged John Garth’s review of Tolkien’s Lay of Aotrou and Itrou–also edited by Flieger, and also gorgeous.

Tolkien and Art

I am fascinated by Tolkien’s own artwork. In some of the Tolkien letters we find out how his humble drawings came to be published with the children’s tale. I decided, though, that I wanted to explore it a little more, and so I wrote, “Drawing the Hobbit.”

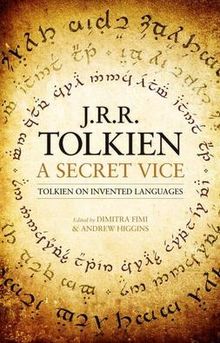

There have been many other illustrators since–including Peter Jackson, whose work as a whole is visually stunning, even for those who don’t feel he was true to the books. One of my favourites was captured in this reblog, “Russian Medievalist Tolkien“–a gorgeous collection of Sergey Yuhimov’s interpretation of The Hobbit.

With the great new editions of unpublished Tolkien by his son, we also get to see some of Tolkien’s original art. I continue to be fascinated by this dragon drawing. What an evocation of the Würme in medieval literature!

I was also blessed throughout the year to wander through two beautiful and rich newish Tolkien books: John Garth‘s The World of J.R.R. Tolkien and the Bodleian Library exhibit text, Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth, edited by Catherine McIlywaine.

I know that the world of Tolkien art is rich beyond my imagination. However, I would like to note that (with permission) I have been using some of Emily Austin’s Inklings-inspired art in my lectures, and keep her 2018 “Niggle’s Country” in my office.

Tolkien’s Worlds and World-building

I would like to spend more time thinking about the speculative universes of J.R.R. Tolkien. Meanwhile, I encourage you to read Jubilare’s reblog of the Khazâd series. It’s just the first of a great series but it shows you a bit of the depth of Tolkien’s world behind the world. In reading up on the Wizards of Middle Earth–the Brown, the White, the Grey, and the two Blues–it struck me how relevant Radagast the Brown is to us today. I take some time here to put a comment that Lewis made about Tolkien’s work in the context of other speculative writers, especially J.K. Rowling.

You can also check out the work of people like the Tolkienist, the links on the Tolkien Transactions to catch what kinds of conversations are about these days, or the academic work of people like David Russell Mosley. And, of course, we are all interested in Tolkien’s work on Beowulf. I read it in 2017 for the free SignumU three-lecture class with Tom Shippey, which is now free on the SignumU youtube channel. Signum continues to offer an MA in Tolkien Studies, and you can feel free to reach out to me for information.

While the Inklings and King Arthur series in Winter 2017 touched on Tolkien all throughout, there are two posts of particular interest. Prof. Ethan Campbell writes about “Wood-Woses: Tolkien’s Wild Men and the Green Knight,” and intertextuality expert Dale Nelson writes about “Tiny Fairies: J.R.R. Tolkien’s ‘Errantry’ and Martyn Skinner’s Sir Elfadore and Mabyna.” Beyond these, we are always on the lookout for new research. So check out the Signum University thesis theatre with Rob Gosselin. I chatted with Rob about his MA thesis on “J.R.R. Tolkien’s Sub-creative Vision: Exploring the Capacity and Applicability in Tolkien’s Concept of Sub-creation.” It’s not only a great conversation about world-building, but a very personal one.

Finally, this post includes resources for Tolkien readers (in conversation with Ursula K. Le Guin): “John Garth, Maximilian Hart, Kris Swank, and Myself on Ursula K. Le Guin, Language, Tolkien, and World-building.”

And Just For Fun….

Well, before the fun but still interesting, I hope, is my post “Stephen Colbert, Anderson Cooper, C.S. Lewis, Tolkien & Me: Thoughts on Grief.” Not super heavy on Tolkien, but we do know that Stephen Colbert is a fan. 2020 also saw two new pieces on Tolkien’s friendships. One was Pilgrim favourite Diana Glyer on The Babylon Bee, talking about “The Tolkien and Lewis Bromance.” The other piece on friendship is “C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien: Friendship, True Myth, And Platonism,” a Paper by Justin Keena. This was the top guest post of 2020, and one of the few times a long, academic paper had gotten a lot of traction on A Pilgrim in Narnia. I think that is a testimonial to Justin’s work, but also a comment about how readers like that Lewis-Tolkien connection that I’ve brought out in some of those letter posts noted above.

For the fun of it…. Weirdly, the top 2019 Tolkien post is my note on “Philip Pullman as a Reader of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien.” It’s short and light and good to get the blood-boiling.

And have you caught my post-Mythmoot post, “The First Animated Hobbit, and Other Notes of Tolkienish Nonsense“? Terribly awesome, awesomely terrible.

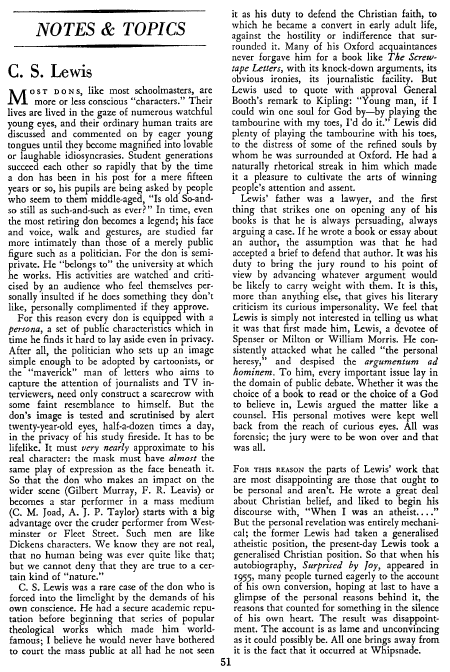

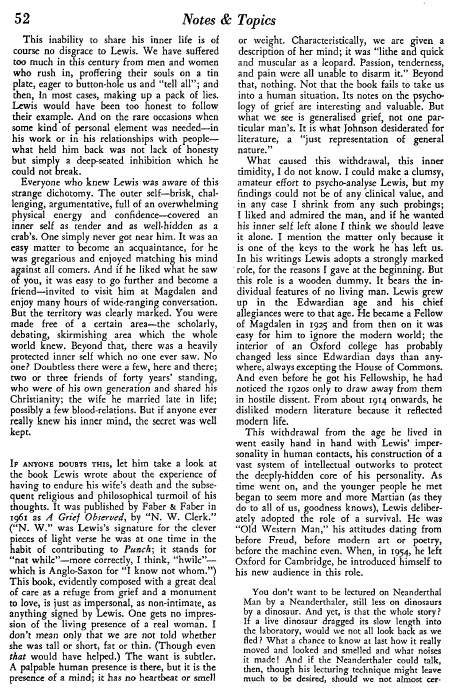

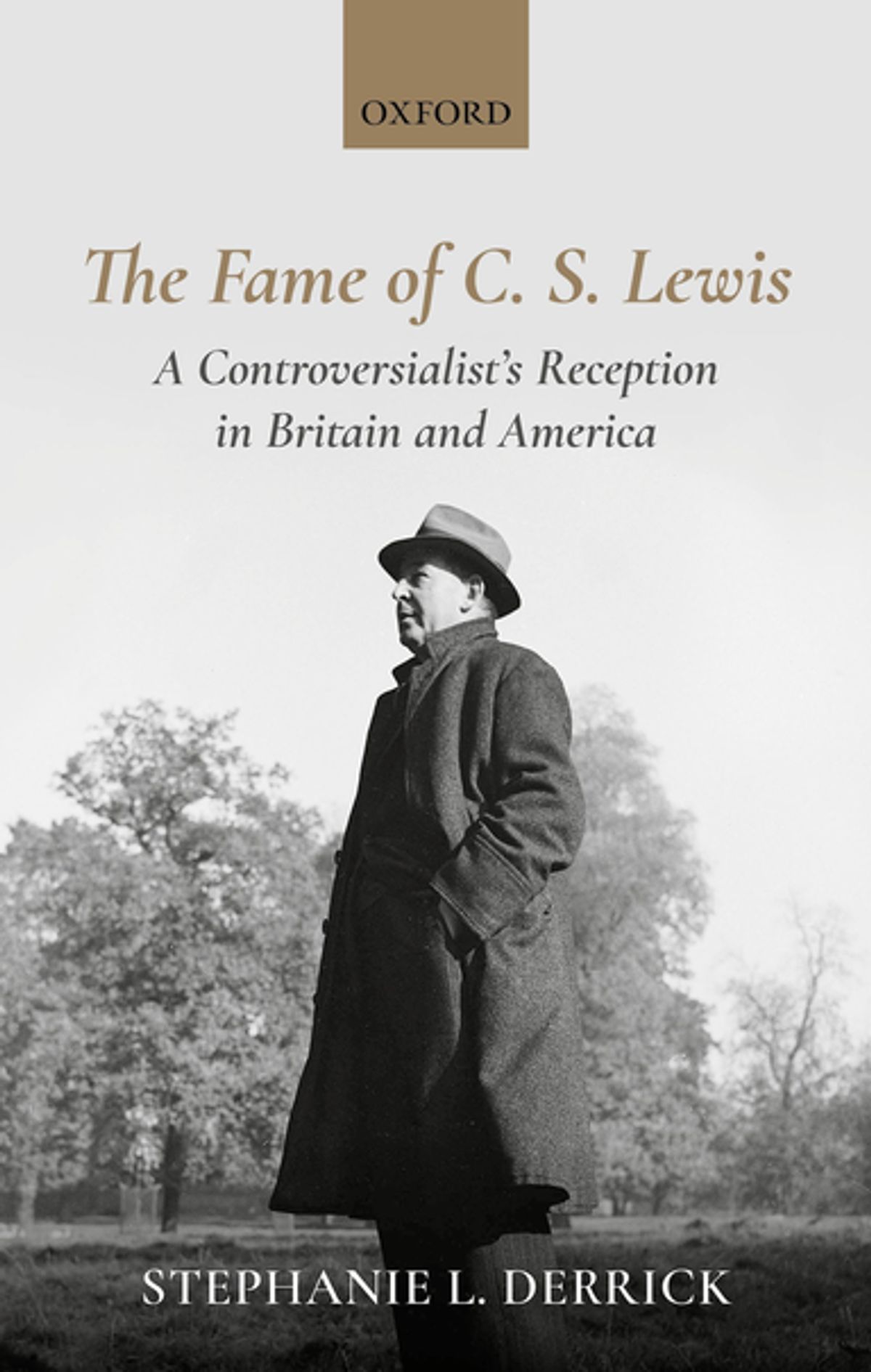

So that the don who makes an impact on the wider scene (Gilbert Murray, F. R. Leavis) or becomes a star performer in a mass medium (C. M. Joad, A. J. P. Taylor) starts with a big advantage over the cruder performer from Westminster or Fleet Street. Such men are like Dickens characters. We know they are not real, that no human being was ever quite like that; but we cannot deny that they are true to a certain kind of “nature.”

So that the don who makes an impact on the wider scene (Gilbert Murray, F. R. Leavis) or becomes a star performer in a mass medium (C. M. Joad, A. J. P. Taylor) starts with a big advantage over the cruder performer from Westminster or Fleet Street. Such men are like Dickens characters. We know they are not real, that no human being was ever quite like that; but we cannot deny that they are true to a certain kind of “nature.”