Hello friends! I want to share what I have been up to in the last few weeks. Some folks will know that I have been working for about nine years on C.S. Lewis’ unfinished teenage Arthurian novel, “The Quest of Bleheris.” Each week in the Spring and Summer of 1916, a seventeen-year-old C.S. Lewis wrote a weekly letter to his best friend, Arthur Greeves. In these weekly epistles, Lewis included a chapter of an Arthurian romance he was working on. This 19,000-word unpublished manuscript was left incomplete after seventeen chapters, but is an evocative piece. As Lewis’ first attempt at long-form prose fantasy, written in the style of William Morris, “The Quest of Bleheris” emerges out of a rich and exciting time in Lewis’s life. Studying under the Great Knock, Lewis is thriving in his literary world and testing out his authorial voice with his best friend. In this period, Lewis has just encountered George MacDonald’s Phantastes, declared his atheism to Arthur, decided to enter the war, and prepared for entrance to Oxford.

More than just teen fan fiction, “The Quest of Bleheris” is a resource for understanding Lewis’ spiritual development and charting his growth as a critic and imaginative writer.

More than just teen fan fiction, “The Quest of Bleheris” is a resource for understanding Lewis’ spiritual development and charting his growth as a critic and imaginative writer.

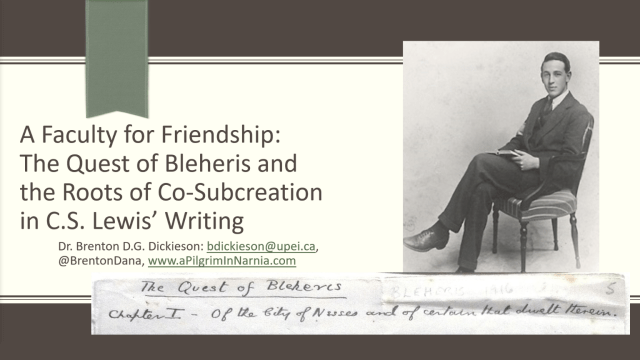

In 2018, I led a panel with Dr. David Downing at the C.S. Lewis and Friends Colloquium (with help from Jennifer Rogers), and in 2022, I presented some findings at the New York C.S. Lewis Society. This past weekend was Canada’s annual Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences (Congress 2023) in Toronto. In 2021, I presented some material from my forthcoming book, The Shape of the Cross in C.S. Lewis’ Spiritual Theology, to the Canadian-American Theological Association (CATA; see description and video here). I have also presented at the Christianity and Literature Study Group (CLSG) on C.S. Lewis’ instinct to write himself into stories (in 2021, see description, resources, and video here) and on language in Lewis’ Ransom Cycle (in 2022, see description here).

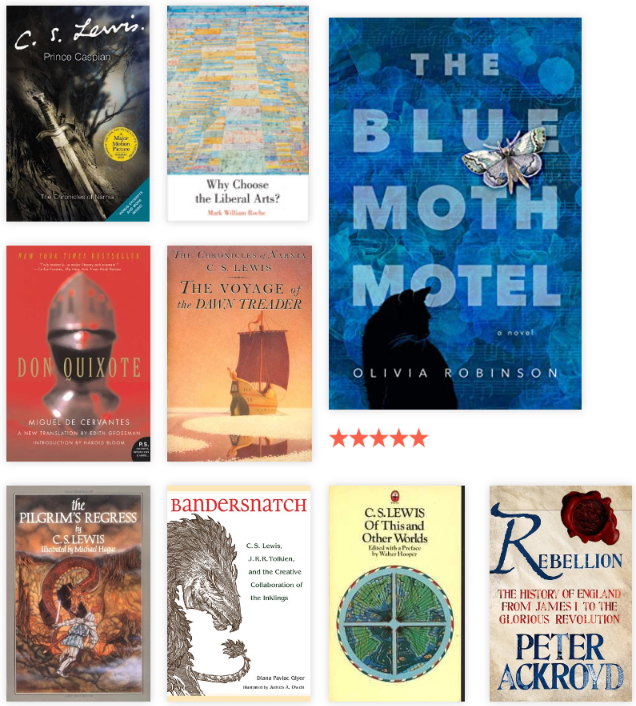

As the Congress–and in particular, the small academic societies within the Congress–is a fruitful place for scholarly discussion, I wanted to present some of my ideas on “The Quest of Bleheris” and what I call C.S. Lewis’ “Faculty for Friendship.” In a work-in-project peer-reviewed paper that I have brought to draft form, I am testing the implications of “The Quest of Bleheris” for Diana Pavlac Glyer‘s theory of creative collaboration among the Inklings. I was pleased when the folk at the CLSG were kind enough to accept my proposal for what is a fairly data-heavy piece.

And then I could not go! I was sad about missing the conference as it was so close (only about a 20-hour drive to Toronto) and because I wanted to connect in real life with my friends at CLSG and CATA. My cancellation also meant, though, that I would leave a hole in the CLSG programme and lose that opportunity to test out my ideas. Again, with great scholarly hospitality, the CLSG folk allowed me to record and present my paper by video.

I am limited from sharing any aspects of the physical manuscript, some particular images, and a portion of the argument. However, I wanted to share a 4-minute segment from my talk for a couple of reasons.

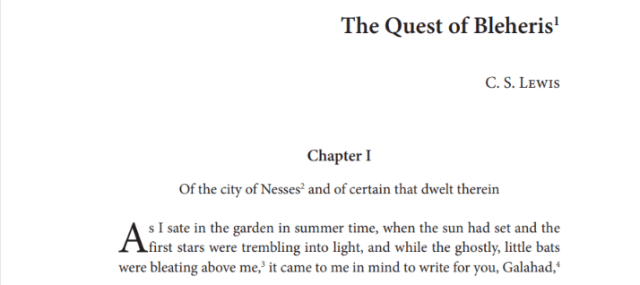

First, “The Quest of Bleheris” has historically been available only to those who could get to archives in Oxford, UK or Wheaton, IL. In 2021, Inklings scholar Don W. King was able to provide a full transcription of “The Quest of Bleheris” in Sehnsucht journal. Recently, Sehnsucht has become an open-access journal. Thus, by clicking on this link, you can find the full transcription of the tale, with critical notes and an introduction by Don King. As this story is now available to the reading world, I hope my short introductory video can give you a feeling for both the story and the manuscript history.

First, “The Quest of Bleheris” has historically been available only to those who could get to archives in Oxford, UK or Wheaton, IL. In 2021, Inklings scholar Don W. King was able to provide a full transcription of “The Quest of Bleheris” in Sehnsucht journal. Recently, Sehnsucht has become an open-access journal. Thus, by clicking on this link, you can find the full transcription of the tale, with critical notes and an introduction by Don King. As this story is now available to the reading world, I hope my short introductory video can give you a feeling for both the story and the manuscript history.

Second, I want to whet your appetite for the paper when I have finally concluded my work. I have spent these years working on this nearly lost piece of Lewis’ writing history because I believe it has deep value for readers and biographers of C.S. Lewis, as well as writers, literary scholars, and WWI historians.

Beneath my 4-minute video, you can find the abstract for the paper and some notes about project. I hope you enjoy, and I welcome any feedback or scholarly questions.

Abstract: A Faculty for Friendship: “The Quest of Bleheris” and the Roots of Co-Subcreation in C.S. Lewis’ Writing

When a seventeen-year-old C.S. Lewis was preparing for Oxford entrance and WWI service in 1916, he wrote seventeen chapters of a prose novel. “The Quest of Bleheris” is a letter-styled chivalric tale of heart-longing for adventure in a latter-days world. Young Bleheris must discover the true meaning of knighthood in a land where King Arthur is a distant memory and chivalry exists only as a formal social game.

Intriguingly, Lewis did not merely write “The Quest of Bleheris” in epistolary form; it is itself an epistolary novel that he mailed in weekly installments to his closest friend, Arthur Greeves. Thoughtful consideration of the extant correspondence, a close reading of the surviving 19,176-word text, and careful analysis of the manuscript show that a culture of creative collaboration goes deep in Lewis’ instincts as a writer. Arthur is implicated at many levels of this tale, both within and without the text. The formation of Lewis’ writerly habits, inspiration for the tale, the form of the novel, critical aspects of the world-building, the atmosphere of the story and the secondary world, critique and feedback, authorial commentary, text illustrations, and the preservation of the manuscript—Arthur was involved at each of these aspects of writing. Again and again, Lewis draws Greeves into the creative process—and goes further, as Lewis imagines he and Arthur, narrator and listener, living within the secondary world as characters. Arthur is there as the story begins to take form, he supports Lewis as he describes all of his doubts and insecurities along the way, and he is the one to whom Lewis announces “Bleheris is dead” some months later.

“The Quest of Bleheris” is an intertextually and autobiographically rich piece. Besides being the literary treasure of a precocious attempt at high romance by one of the 20th-century’s most famous fantasists, the Bleheris manuscript shows early signs of Lewis’ discipline and instincts as a career writer. While the story lacks the inversive elements in his later fiction, it has moments of heightened prose that capture the imagination and open a window into his youthful atheism and love of mythology. It also shows how Lewis instinctively viewed the writing process as going beyond the sole genius model of modern literature to a more capacious medieval model of collaboration, reinvention, multimodal storytelling, and symbolic play. Lewis’ friendship with Arthur extended his image of the “author” beyond the solidary desk to something more like an Arthurian round table experience.

This paper presents evidence for Lewis’ faculty for friendship in the creative process through analysis of the manuscript, the text, and the relevant correspondence. This analysis confirms the work of Diana Pavlac Glyer on collaboration among the Inklings by extending the data to include Lewis’ earliest creative endeavours. We discover the early roots of something like co-subcreation by teasing out Lewis’ instinct challenges us to re-imagining the creative process in these almost-forgotten literary remains.

Notes:

The hand-drawn facsimile of the header of “The Quest of Bleheris” in manuscript form was created by Katie Stevenson, who also did a bit of manuscript help for Sørina Higgins’ The Chapel of the Thorn during her visit to the Wade centre in 2014.

Thanks to Bronwyn Rivera for the note on the “Three Greats.”

I am always grateful to the amazing folk at the Wade and the Bodleian.